In search of a new world order, Russia and China team up to push Ukraine propaganda

By Cynthia Hooper | April 20, 2022

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov visited China in March, where he pivoted from discussing bad news in Ukraine to a vision for a "multipolar, just, democratic world order." Credit: @mfa_russia/Twitter.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov visited China in March, where he pivoted from discussing bad news in Ukraine to a vision for a "multipolar, just, democratic world order." Credit: @mfa_russia/Twitter.

The war in Ukraine is not only about the future of Ukraine. Both Russian and US leaders are making it increasingly clear that the brutal fight for territorial control inside the former Soviet republic is but part of a larger superpower struggle that will determine a new balance of power around the world.

In Iowa to talk about strategies for containing the soaring price of gas, US President Joe Biden termed Russian leader Vladimir Putin a “dictator” who is committing “genocide.” This came a mere two weeks after Biden distressed many of his own staffers by going off-script to invoke god in a call for Putin to be removed from power. Meanwhile, in an interview with Kremlin-controlled television channel Russia-24, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov announced that one of the goals of his country’s so-called “special military operation” in Ukraine was to “end the US quest to dominate the world.”

“What we have here is a war between the US and Russia,” warned University of Chicago Professor John Mearsheimer in a YouTube discussion on April 8. True or not, the power of this idea is one factor in explaining how Putin has been able to shore up domestic public support, with his March approval rating at an alleged 83 percent. “The [Russian] state media skillfully direct the people’s discontent towards the West,” commented one Russian journalist opposed to the war, in an interview with a German foundation.

This determination to “just blame Washington” may sound nothing short of pathetic to many US citizens. But Russia’s media strategists do not seem to care. Instead, they are choosing to pivot their attention away from their Western rivals to focus more on winning new audiences in the former Western colonies and developing countries that comprise the so-called “Global South.” In so doing, the Kremlin is partnering with its most powerful ally. Although there are potential competitors for influence in Africa and elsewhere, these days China and Russia have joined together to promote the idea that the United States is to blame for the Ukraine crisis and its consequences. And they are deploying a variety of tools to get this message across, including cultivating local anti-Western social media “influencers” across Africa, partnering on stories with specific grassroots media organizations, and employing for-pay spam services to tweet examples of US racism and hypocrisy.

This campaign is drawing on a deep reservoir of resentment among former colonies towards wealthier, formerly imperialist NATO countries. And it is succeeding in keeping a significant number of the world’s countries, if not actively on Russia’s side, at least reluctant to wholeheartedly endorse “Team USA.”

Russia and China against the West. Inside Russia, the government has banned journalists from using the term “war” to refer to its military actions in Ukraine, flatly denying that its soldiers have attacked civilians or committed atrocities such as those documented in the town of Bucha. Yet its leaders, from Putin on down, accuse the United States of launching an “economic war” against Russia by imposing sanctions; an “information war” designed to deliberately discredit the actions of Moscow’s armed forces; and a “war of Russophobia” aimed at persecuting Russians abroad and destroying Russian culture.

It’s through this lens that Russian media makers hope people both at home and in developing countries around the world will view the conflict in Ukraine, as a story of a persecuted nation determined to stand up for its interests in the face of US bullying.

And many in China seem to see things the same way.

In diplomatic meetings and state media stories, Chinese establishment figures are siding with Russia on issues like its false allegations of US-led biological weapons research in Ukraine and its criticisms of post-1991 NATO expansion. “NATO has already messed up Europe, stop trying to mess up Asia and mess up the whole world,” proclaimed Chinese diplomat Liu Xiaoming in an angry April post on Twitter.

When Russia’s Lavrov travelled to Beijing late last month to meet with his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi, he took the opportunity to direct attention away from news of Russian military losses, casting the Ukraine “conflict” (not “war”) as an opportune moment for China and Russia to challenge past decades of US global leadership. The two countries, he said, planned to work to bring together all nations similarly dissatisfied with “Western hegemony” and, with them, create a new “multipolar, just, democratic world order.” A Chinese foreign ministry spokesman, Wang Wenbin, enthused, “Our striving for peace has no limits, our upholding of security has no limits, our opposition towards hegemony has no limits,”

One key target of joint Russian and Chinese condemnation is the leveling of economic sanctions on Russia more severe than any ever imposed on a G20 country. The most recent sanctions package bans all new investment in Russia, seeks to disrupt the country’s global supply chains, and further tightens restrictions on its banks. Such measures have led to talk of a Russian default on its external debt, and predictions that the Russian economy could contract by 15 percent in 2022.

Meanwhile, US leaders such as Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen are ramping up criticism of China for failing to support such measures. Speaking to the Atlantic Council on April 13, Yellen endorsed the rather extraordinary strategy of so-called “friend-shoring,” in which “trusted countries” form their own supply chains to reduce dependence on others who could potentially seek to undermine certain foundational values. She also suggested that China risks being cut out of such relationships, saying, “The world’s attitude towards China and its willingness to embrace further economic integration may well be affected by China’s reaction to our call for resolute action on Russia.”

Yellen’s words about the “world’s attitude” seem sure to add fuel to an anger palpable on Chinese social media regarding which countries presume to have the right to speak for that world. In response to pronouncements by Washington last month that “the entire global community” supported sanctions, Zhao Lijian, a combative spokesperson for China’s Foreign Ministry, sarcastically tweeted a map of what he claimed was the US vision of the world. The map included only part of North America, Europe, Australia and Japan, and it left out, among other locations, China, Africa, and India. Zhao’s comments emphasized that the US-led “West” does not include the majority of the world’s population, and that many of those “overlooked” billions of people often do not share its views. Twitter users, some claiming to be “independent journalists” or “anti-imperialists,” retweeted the post more than 12,000 times in a variety of languages.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that when the West talks about the "int'l community", they mean: pic.twitter.com/RZNOwDymX2

— Lijian Zhao 赵立坚 (@zlj517) March 17, 2022

Mutually beneficial propaganda deals. Long before the current crisis, Russia and China began joining forces to spread similarly critical visions of US power via information operations directed to both their own citizens and the wider, non-Western world. According to a recent Brookings Institute report, this propaganda partnership launched shortly after Chinese President Xi Jinping took office in 2012, via a series of content-sharing deals between Russian and Chinese media outlets such as Russia’s English-language media network RT and China’s English-language paper People’s Daily. Efforts to reinforce each other’s “spin” on global events seems to have accelerated in the spring of 2020, as China scrambled to counter Western stories portraying it as the originator of COVID-19.

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February, a Chinese propaganda directive accidentally posted on Weibo revealed yet more signs of behind-the-scenes collaboration. According to the China Digital Times, an online outlet founded by Chinese dissident and UC Berkeley School of Information research scientist Xiao Qiang, the memo instructed Weibo’s army of so-called social media “opinion analysts” (the official term for censors) not to circulate any information “unfavorable to Russia or pro-West.”

In the face of Western outrage at both Russia’s military slaughter of Ukrainian civilians and a Russian domestic disinformation campaign that casts all atrocities as the work of neo-Nazi Ukrainians, both Russian and Chinese officials—and the journalists who cover them—have swung to attacking the United States for its alleged bias in reporting on the war and its causes.

As part of these efforts, the Russian government is organizing trips for foreign journalists into the Donbass region of eastern Ukraine, ostensibly so they can see with their own eyes signs of damage inflicted by Ukrainian troops on pro-Russian civilians and interview Russian-speaking residents about their experiences.

Almost every night for several weeks, the leading Channel One evening news show Vremia has included extensive reports on these excursions, with clips bannered “open your eyes” or “come and see” and featuring soundbites with correspondents from Italy, Iceland, Norway, Greece, and Venezuela, among many others, all testifying to their surprise and shock in discovering the extent of alleged Ukrainian military abuses and of “Western bias” in ostensibly refusing to cover them.

But even as these stories claim to challenge Western censorship, they reveal Russian strategies of information manipulation. Tour guests are described as if they represented respected journalistic establishments from around the world, when in reality, just to take one example, the German reporter prominently quoted on a March 27 show works for the little-known “Anti-Spiegel” organization (Der Spiegel being the Germany’s most prestigious news magazine), which turns out to be an online Russian media company publishing in German.

The same journalist was again featured in April 12 coverage of a tour to Mariupol. In that report, a Channel One correspondent advocated for empowering more “alternative” global media outlets, claiming that appetite was growing around the world for points of view different from those of the Western “establishment.” In a pointed dig at Germany’s Spiegel (which means “mirror” in English) and a direct endorsement of its “Anti-Spiegel” challenger, the Channel One reporter continued on to argue that “many Europeans are trying to see more than just their own reflection in the mirror.”

Chinese media, too, has been emphasizing the need for greater variety in points of view on the global stage (arguably an ironic position, given the importance its leaders place on domestic censorship). Government-sponsored outlets accuse US leaders of arrogant overconfidence in their country’s superiority and fault Western journalists for dismissing any positive coverage of China as “fake.” China’s largest English-language newspaper China Daily—active both inside China and abroad—repeatedly emphasizes these themes. In a China Daily video interview with Victor Gao, a Chinese Communist Party spokesman, about his country’s role in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, Gao stressed that Chinese leaders wanted an end to violence. But he went on to level a blistering, if indirect, critique of Washington, saying that “[w]hat China is opposed to is any country which wants to dictate the terms for the whole world, any country which wants to monopolize power in the world.”

Scramble for Africa. What is important for Westerners to realize is that these narratives are not only staples of domestic propaganda in China and Russia, they are also being deployed by both countries to fuel anti-Western, anti-imperialist sentiments in the developing world and to emphasize differences between rich countries and poor ones. Over and over, Russian and Chinese-funded outlets emphasize that the United States and its Western allies are not listening to developing countries, but instead simply expecting them to obey Washington’s commands. Africa is one key region both countries are bombarding with such propaganda.

At first glance, this situation looks paradoxical, as Moscow and Beijing are themselves natural competitors for influence on the continent. Russia has historic ties to a host of countries in Africa and the Middle East dating back to the Cold War, when the Soviet Union took the lead in supporting African independence movements and a global battle against apartheid and imperialism. China’s dominance on the continent is more recent, dating back to such things as the 2013 launch of the Belt and Road initiative, a 70-country development project that has led to soaring levels of Chinese investment in African infrastructure.

For the time being, however, the potential rivals appear to be making common cause— prompting the US Congress in April to warn of the “malign influence and activities” of Russia in Africa, even while simultaneously worrying about the growing successes of Chinese “soft power” on the continent.

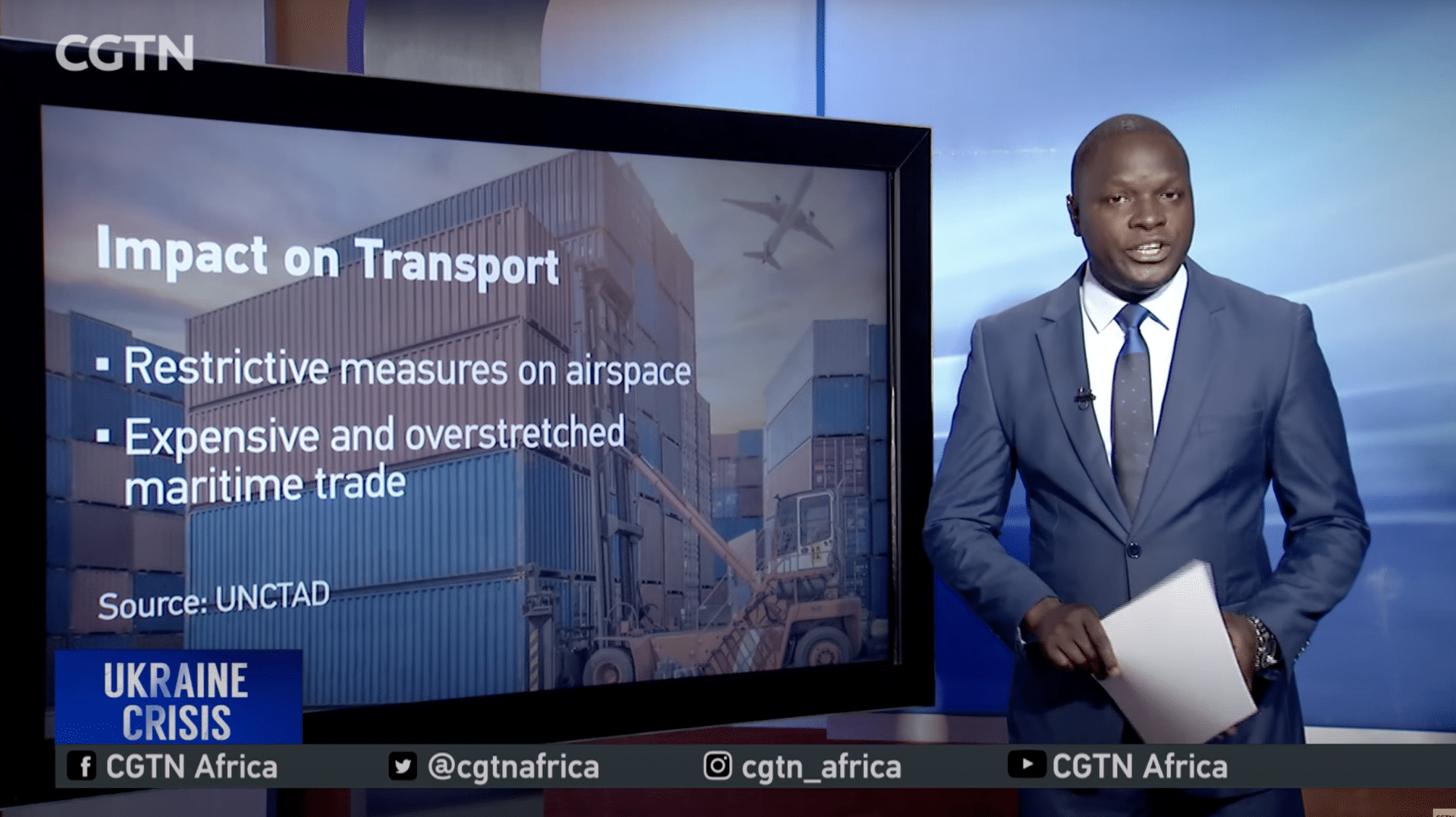

In this battle for hearts and minds, both Russia and China appear to be drawing on a variety of tactics. One is the use of foreign-language, government-funded media tailored to an African audience. Beijing has invested heavily in CGTN Africa, a regional arm of the Chinese Global Television Network founded in January of 2012. China Daily launched an African edition later that same year. Today, the stories both outlets run about the Ukraine war focus on the hardship Africans will face as a result of the conflict. One recent CGTN report emphasized that the price of wheat in Africa rose 19.7 percent in March, alone.

The Kremlin similarly supports a global media network aimed at audiences outside the country. And like CGTN, RT operates inside Africa primarily in English. But RT has also fallen on hard times. Once vastly more popular than its Chinese counterpart, RT has, since the Russian invasion, seen its broadcasts banned in the United States and European Union and its programs thrown off YouTube. But such setbacks in the Western world seem to have encouraged the company to shift its focus. Just weeks before the outbreak of war, RT announced plans to open a new “African hub” in Nairobi, where both CGTN Africa and China Daily Africa are based. The company says it is looking to hire journalists with “a nose for narratives and angles that people from across Africa believe in but [which] are dismissed by mainstream media” and “a strong understanding of how to use digital media creatively to build a passionate and dedicated community.”

According to the Paris-based magazine Africa Report, after RT was taken off the air in France, members of the organization’s Paris bureau began to consider ideas for expanding French-language media coverage in Africa. Several members of the RT Paris bureau are reportedly considering moving operations to West Africa and have already opened discussions with an online media service in Mali known for its alleged ties to the Russian paramilitary organization Wagner Group, active in that country since 2020.

If these relationships sound convoluted, not to mention sketchy, that is because they are. Africa Report has also documented the emergence of pro-Russian social influencers and bloggers across Africa, and their investigation points to a pattern in which seemingly apolitical organizations (such as “think tanks” or “research centers”) are created to serve as intermediaries between a variety of grassroots (and often very fringe) African media outlets and major Russian propaganda operatives such as Yevgeny Prigozhin, head of the notorious St. Petersburg “troll factory,” the Internet Research Agency accused of multiple disinformation campaigns and interference in the 2016 US Presidential election.

More recently, groups linked to Prigozhin have, in Africa, been accused of fabricating scandals to discredit independent journalists, manipulating public opinion at the behest of local potentates, and mounting coordinated disinformation campaigns designed to promote Kremlin goals. Facebook has also begun to identify significant amounts of suspicious activity originating from Russia and aimed at African social media. In December of 2020, Facebook announced it had taken down more than 500 “inauthentic” accounts “originating from Russia and France” and “targeting 13 African countries,” while Facebook’s first “adversarial threat report” of 2022 mentioned a network originating in St. Petersburg and targeting “primarily Nigeria, Cameroon, Gambia, Zimbabwe, and Congo.”

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a variety of opaque online services appear to be promoting pro-Putin or pro-Russian hashtags and linking them to anti-Western, anti-imperialist, or pan-African commentary. Carl Miller, research director at the Centre for the Analysis of Social Media, mapped approximately 10,000 accounts that circulated pro-invasion hashtags on March 2 and March 3, and his results suggest that Russian propaganda forces likely rented out pay-to-engage services located in Africa and Asia to boost coverage. His findings, he notes, suggest this operation was not an isolated incident, but, instead, part of a much larger “BRICS-solidarity influence strategy” designed to unite poorer countries with growing economies against more established, wealthier ones.

It is worth noting, in this regard, that although China is currently Africa’s largest creditor, owed more than $140 billion, its leaders have—ever since its emergence as a unified Communist state in 1949—always publicly emphasized their country’s solidarity with the developing world. In a recent editorial for the South China Morning Post, government researcher Zhou Xiaoming stressed his country, too, was an “emerging economy,” called the nations of the Global South “cousins,” and claimed China, like them, had “resisted the pressure to align itself with the West over the war in Ukraine.”

Empathy disrupted. So does such propaganda really work? And, whether covert or overt, does it succeed in transforming people’s values, or merely in highlighting opinions deeply rooted in society, if not always openly expressed?

Certainly, the situation in Africa is fraught. In regard to the war, many citizens seem to be struggling to identify the lesser of two evils: They are unhappy with Russia’s actions in Ukraine, but even more unhappy with US actions in the wider world. Support for the Kremlin is less than solid. Thirty-seven out of 54 African countries voted to condemn the Russian invasion at the UN, whereas only 28 voted to condemn the annexation of Crimea in 2014. Nevertheless, not a single country in Africa (or in the Middle East or Latin America) has joined in on US and EU sanctions.

My colleague at the College of the Holy Cross, history professor Munya Munochiveyi, told me that many Africans perceive sanctions as a neo-colonialist tool, “a sort of 21st century version of European imperialism.” Zimbabwe’s acting minister of foreign affairs, in an article for The Herald, one of his country’s major papers, claimed that sanctions against Russia represent only the will of the United States and its closest allies, noting that his own country has been forced to endure US sanctions for over 20 years. “Unilateral sanctions have never worked to resolve any situation,” he declared. “On the contrary, sanctions unleash untold humanitarian crises and human suffering of the ordinary people.”

It is in the ability to hamstring the construction of a more genuine global alliance, whether today against Russia or tomorrow against a threat like global warming, that anti-US messaging is most powerful. As Munochiveyi told me, “Social media is a perfect vehicle to stir up historical memories of imperialism in the Global South.” And due in part to the very real power of those memories, but also in part to the power of their online amplification, billions of people around the world see the United States as an arrogant and hypocritical country that pursues its own interests, while pretending to a moral superiority it does not deserve. On April 14, the Russian embassy in the United Kingdom tweeted a comment by Putin, in which the Russian president once again accused the United States and its allies of viewing the Ukrainian people as no more than puppets in a larger power struggle. “The main goal of the West is not to help Ukraine,” this particular quote read. “Ukraine is just a means of reaching goals that have nothing to do with the interests of the Ukrainian people.” It’s the same line Chinese journalists emphasize when they disparage Washington for allegedly expecting to be able to give the countries of Africa orders and have them fall in line. Africa “has matured and is unwilling to be used as a rubber stamp to undermine or confront other countries,” proclaimed a March CGTN Africa article.

It is, of course, deeply ironic that Russia and China, both superpowers with extensive records of human rights abuse, are expressing outrage over another government’s alleged disregard for ordinary people and their opinions. But at the moment, their information war, in order to be successful, merely needs to undermine trust. It is always difficult to persuade countries to act selflessly on a global stage, in a manner at odds with their economic self-interest. But it is all but impossible if citizens are encouraged to believe that the only result of selflessness will be further exploitation.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: China, Russia, Ukraine, propaganda

Topics: Disruptive Technologies