Polio is back. Here’s what to do about it.

By Kathleen E. Bachynski | August 18, 2022

A 2014 illustration of a polio virus particle, from the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Image courtesy of Sarah Poser, Meredith Boyter Newlove/CDC

A 2014 illustration of a polio virus particle, from the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Image courtesy of Sarah Poser, Meredith Boyter Newlove/CDC

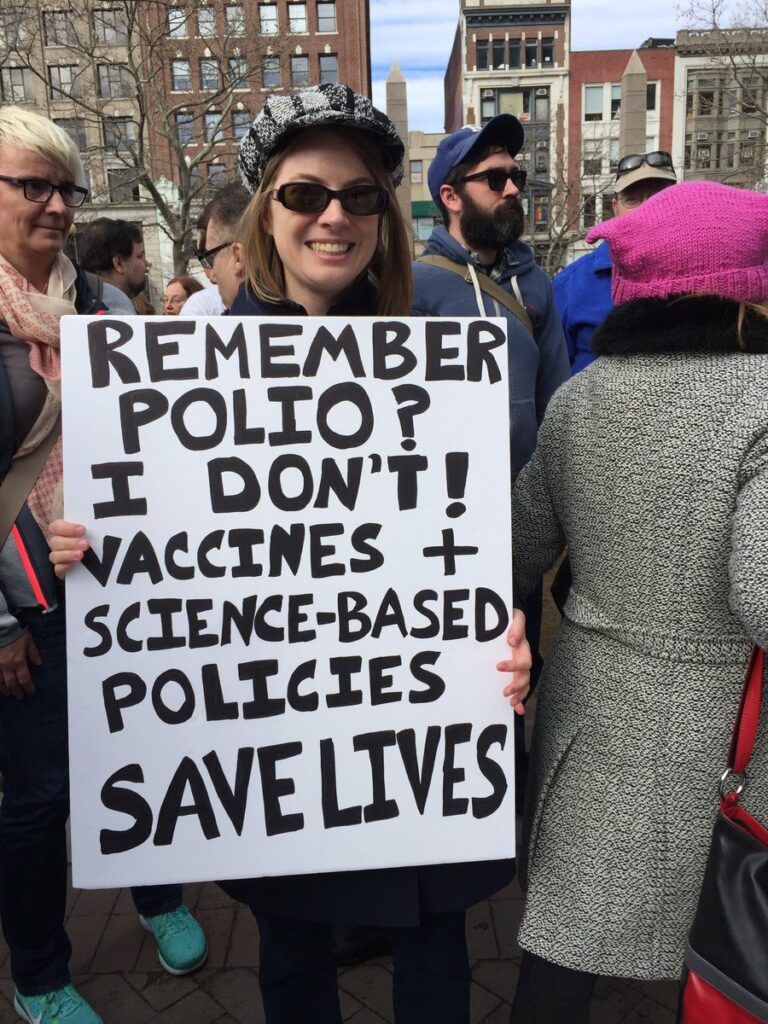

“Remember polio? I don’t! Vaccines + science-based policies save lives.”

I wrote those words on a poster board in 2017. I was worried about outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, such as measles at Disneyland in 2014 and whooping cough in Washington State in 2015. I was also concerned about anti-vaccine rhetoric that I was hearing from politicians across the political spectrum. So I picked up some sharpies and made a sign celebrating the power of vaccines to protect people against devastating diseases.

Unfortunately, five years and one global respiratory pandemic later, I’m no longer quite able to say that I don’t remember polio. This summer, an unvaccinated man in Rockland County, New York, was confirmed to have a case of paralytic polio. The news led public health officials to sound the alarm, because most people infected with polio are either asymptomatic or have mild symptoms. Consequently, as New York State Health Commissioner Mary Bassett explained, “For every one case of paralytic polio identified, hundreds more may be undetected.” Last week, polio virus was identified in New York City wastewater, further reinforcing concerns about local circulation of the virus.

If everybody were fully vaccinated against polio, there would be little cause for alarm. Three doses of polio vaccine (still part of the standard immunization schedule for children) are approximately 99 to 100 percent effective against paralytic polio. It doesn’t get much better than that.

But not everybody is vaccinated. Although all 50 states and the District of Columbia have laws requiring childhood vaccinations before entering school, enforcement varies—and there are permitted exemptions, which also vary from state to state. Moreover, remote schooling during the Covid-19 pandemic made enforcing school vaccine mandates more challenging. Disruptions to health services and delayed care-seeking further contributed to a decline in polio vaccination coverage.

Consequently, in Rockland County, only about 60 percent of children under two years old are vaccinated against polio. In some parts of the United States, that number is even lower. Unvaccinated children and adults are at risk for the most dreadful consequences of this virus, including paralysis, post-polio syndrome (which includes chronic symptoms like loss of muscle function and joint pain, that can develop decades after initial polio infection), and death. As a CDC report put it, “Even a single case of paralytic polio represents a public health emergency in the United States.”

Even more alarming, this outbreak of polio in New York is only the tip of the iceberg of a much bigger global health threat. Slipping vaccination coverage was already a major concern before the Covid-19 pandemic. But the last two years have seen significant disruptions of vaccination programs associated with Covid-19 response measures, social media misinformation campaigns, and displacement of peoples in the wake of war and natural disasters. All these factors have led to the sharpest drop in routine childhood vaccinations in 30 years. On a global scale, this translates to tens of millions of children at risk for contracting and spreading diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, polio, measles and a host of other vaccine preventable diseases.

This is a public health emergency and must be treated as one. The development of safe, effective Covid-19 vaccines within the span of a year showed what we can accomplish when we make developing a public health solution a priority. But an uneven vaccine rollout and inadequate Covid-19 vaccination coverage also showed what can happen when we focus on a technological breakthrough without also investing in getting everybody vaccinated.

Successful vaccination programs fundamentally depend on community trust, outreach, education, policy, and public health infrastructure. That’s what it’s going to take to protect people from needlessly suffering and dying. Here are just a few places to start:

Strengthen on the ground community outreach

Public health depends on trust, and trust depends on building relationships with people. As Lily Caprani, head of advocacy for UNICEF, told the New York Times, “We aren’t going to solve this with poster campaigns or social media posts. You need outreach by reliable, well-trained, properly compensated community health workers who are out there day in, day out, building trust—the kind of trust that means you listen to them about vaccines.” Community health workers are particularly well suited to having meaningful conversations about vaccines that are rooted in care and cultural sensitivity, not shame or stigma. But countries across the world, including the United States, do not currently have enough community health workers to meet this need. Recruitment, training programs and proper compensation for community health workers must be a top priority.

Celebrate and communicate public health successes

Public health successes are too often invisible. When we turn on the tap and clean drinking water comes out, we rarely think about the infrastructure that makes that possible. If we’ve never met anybody who’s experienced polio or tetanus, it’s easy to take the power of vaccines for granted.

It’s much easier to see public health failures, so we need to do a better job of making public health successes visible. We should celebrate our older relatives who are alive and healthy today because they got vaccinated for polio as children. We should rejoice at how many young people don’t have go through painful treatments or die far too soon thanks to the strong protection of the HPV vaccine against multiple cancers.

We should also ensure that education about how vaccines work becomes a regular part of school curricula. Everybody deserves a basic understanding of how vaccines work. Greater vaccine literacy would help protect against disinformation and empower people to confidently choose to get themselves and their children vaccinated.

Invest in public health infrastructure

Public health infrastructure is critical to vaccine delivery. Yet public health remains woefully underfunded in the United States. Funding is often unpredictable, haphazard, and subject to the whims of politics. We need strong and sustained investment in our public health workforce at all levels, from local health departments to federal health agencies.

In addition to resources and staff, health officials need the authority to implement public health policies to safeguard public health. Yet a 2021 analysis found that more than half of U.S. states have weakened the powers of state and local health officials to protect communities from the spread of infectious disease. Notably, “at least 17 states passed laws banning covid vaccine mandates or passports, or made it easier to get around vaccine requirements.” This is a move in exactly the wrong direction. As Kelley Vollmar, executive director of the Jefferson County Health Department in Missouri, put it “It’s kind of like having your hands tied in the middle of a boxing match.” Public health officials must be empowered to implement and enforce policies that prevent the spread of dangerous infectious diseases.

Prioritize global vaccine access

As Covid-19 and monkeypox have demonstrated all too clearly, infectious diseases spread across borders and threaten people across the world. Yet vaccine access remains profoundly inequitable. Only about 10 percent of people in low-income countries have received even a single dose of Covid-19 vaccine. These inequities, coupled with troubling declines in childhood vaccination coverage in countries across the world, threaten everybody’s health. Policies are critically needed to support vaccine production, supply chains and equity on a global scale.

Vaccines are one of the greatest public health achievements in human history. Yet in the United States alone, the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic is still killing hundreds of Americans every day. Monkeypox continues to spread as vaccine distribution systems stumble. A young man in Rockland County has been paralyzed from polio. All my concerns about outbreaks of vaccine preventable diseases have been magnified a thousand-fold since I made that sign in 2017. It is even more urgent that we raise our voices to demand that our leaders do everything it takes to prevent unnecessary death and suffering from diseases that threaten us all. And we must continue to tell the the extraordinary public health success stories made possible by vaccination programs based in trust, strong public health infrastructure, and equity. Vaccines and science-based policies save lives.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: COVID-19, polio, public health, vaccination, vaccines, virus

Topics: Opinion, Science Denial