Memories of Mikhail Gorbachev—and a unique time in Russian history

By Rose Gottemoeller | August 31, 2022

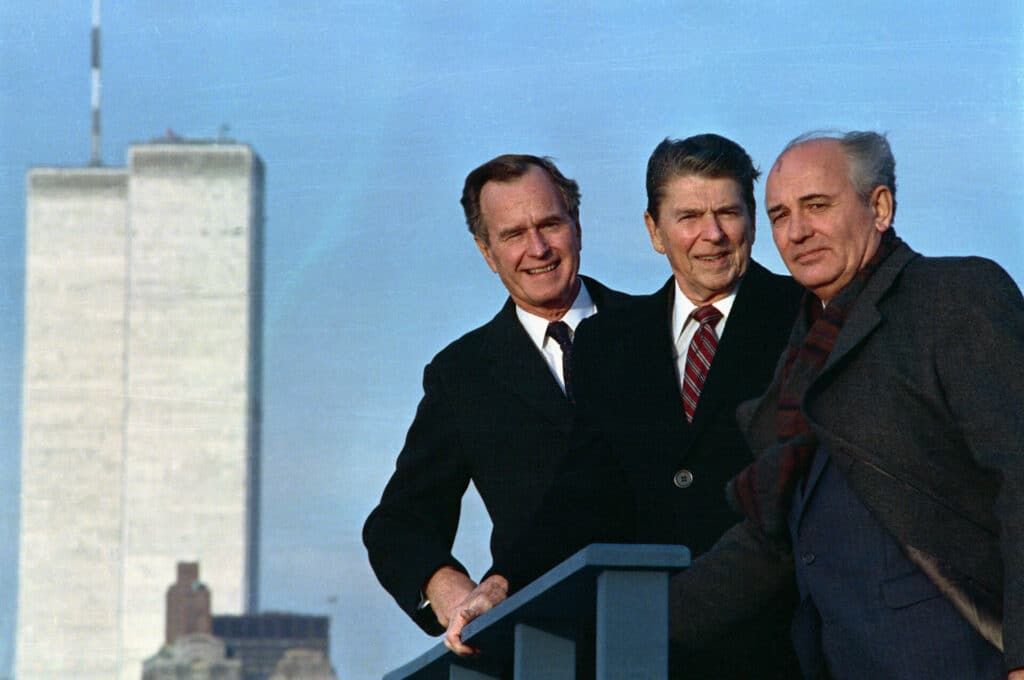

After a meeting in New York, President Ronald Reagan, Vice President George Herbert Walker Bush and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev pose with the World Trade Center in the background.

After a meeting in New York, President Ronald Reagan, Vice President George Herbert Walker Bush and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev pose with the World Trade Center in the background.

So many wonderful things have been said of Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev in recent days that I am loath simply to repeat them. Instead, I have reached back for my own memories, those that brought home to me his unique place in Russian history. Of course, you would expect that I would sing kudos for his role, together with Ronald Reagan, in halting the nuclear arms race in the 1980s. Their 1986 meeting at Reykjavik was a breakthrough that led within a few years to the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF), and within a few years more to the first Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START).

What I recollect from Reykjavik, however, was my astonishment at news reports on the first day that Soviet General Secretary Gorbachev and American President Reagan were considering abolishing ballistic missiles and the nuclear weapons that went on them. At the time a young analyst at RAND, I knew the debates that had been raging in our own system about undertaking reductions in nuclear weapons, never mind abolishing them. “Richard Perle,” I thought, “must be furious over this.”

Perle was a notable hawk from the Department of Defense and member of Reagan’s Reykjavik delegation. I figured his Soviet counterparts must be even more furious, since the Soviet Union was so dependent on nuclear weapons. “This is not going to stick,” I said to myself, and sure enough, by the next day there was no more leadership talk of abolishing nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles. The ground had been laid, however, for the INF and START agreements.

After Reykjavik, it really came home to me that Gorbachev was changing the Soviet Union when I visited the country for a RAND project in 1989. One freezing night, I had dinner with embassy friends Mike and Marlena Hurley and then got a ride back to my hotel in their Soviet-made SUV, the Niva brand. I remember it had no heat, and Mike had to scrape the internal windshield while he drove. But it sure could handle the icy roads.

Mike’s assignment during that stint in Moscow was to try to get a handle on whether “glasnost’” was real. Glasnost was the opening of society, including the media, to debate and discussion, something that had not been tried since the brief “thaw” under Nikita Khrushchev in the late 1950s. Mike went about his assignment by trying to get an American article on arms control printed in Izvestiya, which was one of the two premier Soviet national newspapers (the other being Pravda). Max Kampelman, the chief US nuclear negotiator, authored the piece, which was entitled “Negotiations in Geneva: An American Evaluation.” In theory, it was turnabout for a piece that the New York Times had requested from the Soviet nuclear negotiator Yuly Vorontsov.

After a struggle, Mike did manage to get the piece placed, although Izvestiya published it with ill grace. They introduced the article with the following comment: “This article arrived at the editorial board from the U.S. Embassy in Moscow with … a request to publish it, as Yu. M. Vorontsov’s article had appeared in the NY Times… We didn’t see that there was an equivalence in this situation, but decided to publish it… We note that the circulation of Izvestiya exceeds that of the New York Times by a factor of 10.” Never mind the sour grapes, glasnost had arrived. It was real.

As Gorbachev’s presidency unfolded, it became clear that he was not going to be like the dour and geriatric Soviet Politburo members Leonid Brezhnev, Yury Andropov, and Konstantin Chernenko, who had followed each other in quick succession to the Kremlin leadership in the early 1980s. Only 54 when he took office, Gorbachev was easily the most dynamic figure seen in Moscow for nearly 30 years, with the confidence to speak openly on the public stage with foreign leaders such as Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

I liked it best that he did not hide his wife from view. The Soviet era had continued a long Russian tradition of keeping the women and children out of the public eye—cloistered in secrecy—a tradition, by the way, to which Vladimir Putin has returned. Not so with Mikhail Gorbachev. He proudly took his wife Raisa on trips to meet foreign leaders and attend summits. They were out on the streets talking to people at home, too, so Soviet audiences could understand clearly that times were changing.

This policy was not universally popular, running against a deep, patriarchal strain of Russian history. It also ran up against old Russian superstitions that at least partially explain the pronounced misogyny that colors so much of Russian life even today. I thought it was terrific, for example, that Raisa Gorbacheva appeared together with her husband on the deck of a Soviet submarine during an inspection of the crew. Afterwards, however, the sailors reportedly grumbled that having a woman on board was bad luck and would lead to trouble later on—a kind of female Jonah story. I was horrified when I heard this and reflected sadly afterwards that it would be a long time before Russian women would be serving on naval vessels of any kind, never mind submarines.

My only personal encounter with Gorbachev came many years later, when I worked in Moscow as director of the Carnegie Moscow Center. A Russian friend who was an associate of Gorbachev asked me if I would like to attend a lunch to celebrate his birthday. “Of course!” I said. It was an honor for me.

I was pretty much a fly on the wall during the proceedings, since I could keep up with the fast conversation but did not want to display my less-than-perfect Russian to the former president. Nevertheless, he received me kindly. One exchange has always stuck with me. One of his former staffers from his time in the Kremlin asked him, “Mikhail Sergeevich, when have the security services—the KGB, FSB, GRU—been more of a threat? Now, or during the Soviet era?”

Gorbachev thought about it for a moment and then said, “During the Soviet era, at least the Communist Party Central Committee kept them under control. Now, they have no one to answer to but themselves. They are more of a threat now.” He was right.

Rest in peace, Mikhail Sergeevich.

Editor’s note: Portions of this article will also appear in the Stanford Daily, the independent, student-run newspaper of Stanford University.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Mikhail Gorbachev, Raisa Gorbacheva, Ronald Reagan, glasnost

Topics: Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons