Subscribers can read every back issue of the Bulletin.

From the Archive: 1945-2025

Get the Bulletin's digital magazine and access to the archive for less than

$5 a month

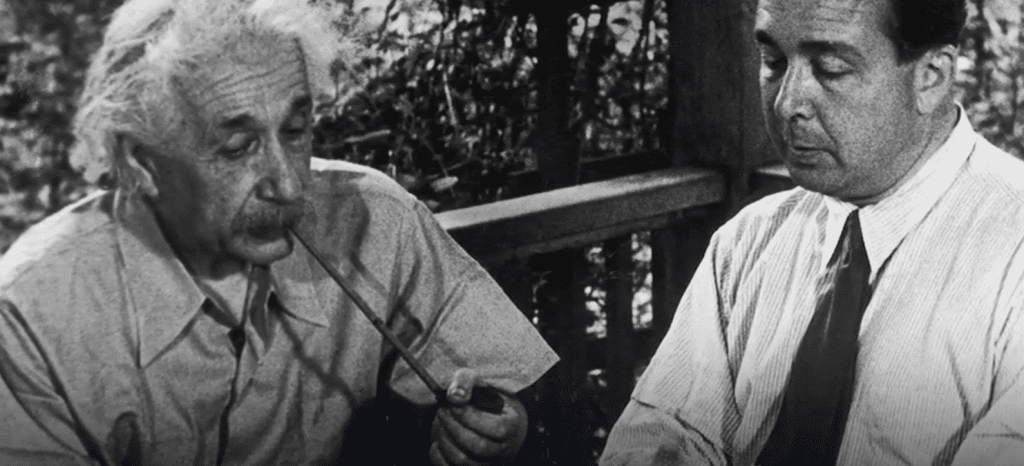

A policy for survival: A Statement by the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists

By Albert Einstein, et al.

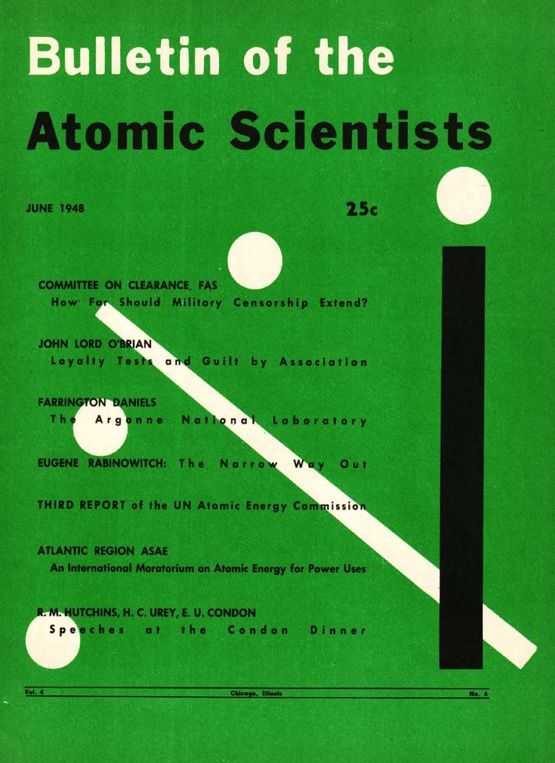

Published in the June 1948 issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

This is a free preview of a premium archival article published on April 12, 1948. Subscribe now to access our full archive here.

"No one has the right to withdraw from the world of action at a time when civilization faces its supreme test."

I

Two years ago this month the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission was in process of formation. Now the discussions on international control of atomic energy are about to be adjourned indefinitely, perhaps never again to be resumed. One of the most fateful events in history has passed almost unnoticed. Its importance must be realized: its lesson for mankind must be made clear. To clarify the importance of the collapse of these discussions, we reiterate here our Six Point Statement published originally on November 17, 1946:

- Atomic bombs can now be made cheaply and in large number. They will become more destructive.

- There is no military defense against atomic bombs and none is to be expected.

- Other nations can rediscover our secret processes by themselves.

- Preparedness against atomic war is futile, and if attempted, will ruin the structure of our social order.

- If war breaks out, atomic bombs will be used and they will surely destroy our civilization.

- There is no solution to this problem except international control of atomic energy, and ultimately, the elimination of war.

Every scientific development in the intervening seventeen months has supported the accuracy of this statement. Yet the negotiations by which international control of atomic energy was to be achieved have collapsed.

II

This is a time for taking stock of reality and facing up to the facts. The most salient fact confronting our civilization is that the hope of One World is frustrated; today two hostile worlds are in full contest, the Eastern bloc headed by the Soviet Union confronts the Western democracies. Three possible lines of policy are emerging in the West:

- The first policy is that of the preventive war. It calls for an attack upon the potential enemy at a time and place of our own choosing while the United States retains the monopoly of the atomic bomb. Let us not delude ourselves that victory would be cheap and easy. At the outset the Russians must occupy all of Europe up to the Atlantic seaboard from which they could be dislodged only by large scale bombardment of cities and communication centers. No military leader has suggested that we could force a Russian surrender without a costly ground force invasion of Europe and Asia. Even if victory were finally achieved after colossal sacrifices in blood and treasure, we would find Western Europe in a condition of ruin far worse than that which exists in Germany today, its population decimated and overrun with disease. We would have for generations the task of rebuilding Western Europe and of policing the Soviet Union. This would be the result of the cheapest victory we could achieve. Few responsible persons believe in even so cheap a victory.

- The second possible policy is maintenance of an armed peace in a two bloc world which, historically, has always led to war. This course would lead to rebuilding the strength of Western Europe economically and militarily to a point where, allied with the United States, it would confront the Soviet bloc with overwhelming strength. This would entail tremendous and steadily accelerating armaments expenditures over an indefinite period, enforce a lower standard of living on the people, and might betray our moral position by propping up anti-democratic regimes as counterpoise to the Russians. But it could have no termination save in a war begun at a less advantageous moment than the preventive war and thus ending even less favorably.

- A third possible policy is the drive for World Government which has little support among governments but has growing and powerful support among the peoples of the West. Stripped of the enthusiasm of its friends and the misapprehensions of its enemies, the World Government movement looks toward a creation of a supranational authority with powers sufficient to maintain law among nations. Initially and at every step the door would be open to all nations to federate with the supranational authority and submit to its limited jurisdiction.

Is this a hopeless perspective? We think not. The American proposal for international control of atomic energy was accepted in its essentials by the nations outside the Soviet bloc. Through its abolition of the veto power in the field of atomic energy it would have had the effect of transferring sovereignty in this field to the international authority. In substance this was a world government in a limited sphere.

The first two suggested policies lead inevitably to a war which would end with the total collapse of our traditional civilization. The third indicated policy may bring about the acceptance by the Soviet bloc of the offer of federation. If they will not accept federation, we lose nothing not already lost. If as seems probable, the world has a period of an armed peace, time and events may bring about a change in their policy.

We have then the choice of acceptance, in the first two cases, of the inevitability of war or, in the latter case, of the possibility of peace. Confronted by such alternatives we believe that all constructive lines of action must be in keeping with the need of establishing a Federal World Government.

III

World Government can be achieved, but cannot be achieved overnight. In the meantime statesmen must confront today's problems and attempt to solve them, lest there be no civilized world left to govern. The course of events has indicated a growing dependence on armaments, at a time when armaments cannot be adequate for purposes of national defense, and a decreasing use of the processes of negotiation and conciliation.

There are no serious negotiations going forward anywhere in the world between the two great powers, the United States and Soviet Russia. Almost everywhere the pattern is the same—total collapse of discussion on the most important problems—in the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission, in Berlin, in Korea.

We hope for discussion and negotiation at the highest governmental level—if need be, in secrecy in the initial stages—keeping in mind at all times the ultimate goal of peace through world government. We understand and share the distaste among democratic people for secret negotiations. But we see no hope under present conditions for any settlement to come out of public negotiations in which each statesman is the prisoner of his national prestige.

This call to negotiation does not mean appeasement. Every member of this Committee was opposed to Munich at the time of Munich, and we are equally committed today to the maintenance of the spiritual and physical bounds of freedom throughout the world. We are deeply disturbed by the conversion of Czechoslovakia into a police state.

IV

We make public our position in the belief that in a democracy it is the duty of every citizen to contribute to the clarification of issues and to the solution of the great problems which confront all of us. Scientists have a special position in the tragic situation in which mankind exists today. It is through the work of the scientific community that this great menace has come upon humanity and now threatens to destroy our civilization.

We are all citizens of a world community sharing a common peril. Is it inevitable that because of our passions and our inherited customs we should be condemned to destroy ourselves? No one has the right to withdraw from the world of action at a time when civilization faces its supreme test. It is in this spirit that we call upon all peoples to work and to sacrifice to achieve a settlement which will bring peace.

Albert Einstein, Chairman

Harold C. Urey, Vice-Chairman

Harrison Brown

T. R. Hogness

Joseph E. Mayer

Philip M. Morse

H. J. Muller

Frederick Seitz

© Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists