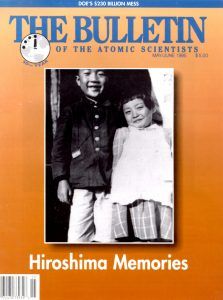

1995: Hiroshima Memories: One sunny day, a young girl learned about darkness

By Hideko Tamura Friedman | December 7, 2020

1995: Hiroshima Memories: One sunny day, a young girl learned about darkness

By Hideko Tamura Friedman | December 7, 2020

Editor’s note: The Bulletin originally published “Hiroshima Memories” in its May/June 1995 issue. It was adapted from a longer unpublished work, “One Sunny Day,” by Hideko Tamura Friedman, a therapist in private practice and part-time social worker in the Radiation Oncology Department at the University of Chicago Hospitals. She was a child in Hiroshima when the city was destroyed in 1945 by an atom bomb. She came to the United States in 1952, after finishing high school. The article is republished here as part of a special issue commemorating the 75th year of the Bulletin.

Today I live in the United States where I’m a social worker in the Radiation Oncology Department at the University of Chicago Hospitals. The work is rewarding. Over the decades, the diagnostic and therapeutic uses of ionizing radiation have probably helped millions of people around the world.

But just a few blocks away is a monumental bronze sculpture by Henry Moore. It is called “Nuclear Energy,” and it marks the spot where Enrico Fermi’s talented team of Manhattan Project physicists achieved the first self-sustaining chain reaction in December 1942. To me, “Nuclear Energy” terrifyingly resembles a mushroom cloud, and I avoid going near it.

But just a few blocks away is a monumental bronze sculpture by Henry Moore. It is called “Nuclear Energy,” and it marks the spot where Enrico Fermi’s talented team of Manhattan Project physicists achieved the first self-sustaining chain reaction in December 1942. To me, “Nuclear Energy” terrifyingly resembles a mushroom cloud, and I avoid going near it.

Perhaps that is because I recall a warm sunny day in another city, when I was a child of 10. On that day, August 6 in Hiroshima, the sun and the earth melted together. On that day, many of my relatives and classmates simply disappeared. I would never again see my young cousin Hideyuki, who had been like a brother to me, or Miyoshi, my best friend. And on that day of two suns, my Mama would not come home for lunch.

Mama and Papa

Tokyo was my home until Japan invaded China. During the war, Papa was drafted into the Imperial Army in 1938. He first served as a private in Northern China; after Pearl Harbor, he became a high-ranking logistics officer based in Hiroshima, his home city.

During most of the war, Mama and I lived with Papa’s family, the Tamuras, one of the most respected families of the city. Their home-actually, a large and elegant estate on the Ota River, just over a mile from the center of Hiroshima-would be a war-time refuge. The Tamuras would make sure Mama and I were well cared for.

Papa, Jiro Tamura, was the second son of Hide taro Tamura, the founder of the Tamura cartel, a combine that produced sewing needles and rubber goods. It had branches in China and Manchuria, and employed about 3,000 people. Grandpa Tamura was a kindly man, even in business. Among his workers were handicapped men and women only he would hire. He made sure the job was fitted to their abilities. I especially remember “Bensan,” who had severe curvature of the spine. He had light duties at the factory, and he used to help in the gardens at the Tamura estate. I also remember the time a man who had become unhappy at work climbed to the top of a 60-foot chimney. Grandfather shut down the factory so the man would not be harmed by heat and smoke, and he waited for the man to tire and come down. Grandfather died of a heart attack before the end of the war. Perhaps that was not such a sad thing.

My Papa had thick, dark brown, curly hair, quite like the painter he had always wanted to be. He was of average height, but wiry and powerful. His sturdy shoulders carried me as we strolled among the Yomise vendors after supper. During the week, he worked for Nissan Motors in Tokyo as a salesman. On weekends, he painted. In earlier years, he had wanted to attend the Tokyo Art Institute rather than law school. But his parents did not permit him to do that. “Art” was not a substantial profession for a Tamura man.

My mother, Kimiko Kamiya, was “Mama” to me, never Oka-san (mother). She was slender and tall. Her large, expressive eyes, long thick eyelashes, and well-defined eyebrows were not typical Japanese features. She was striking when she dressed up; heads turned when she walked down the street.

Like other Japanese mothers, and she was always busy cooking, sewing, knitting, and cleaning house. She made all my clothes, she was a speedy knitter. Everything seemed effortless to her, whether making dolls or teaching me how to fold an origami “ghost” on a rainy day. Step by step, she took me through the intricate folding process with the simple square papers. It was like magic.

Years later, I saw “The King and I,” and I was reminded of Mama. Like Anna, she shared her open spirit with others by singing. Her voice was soft, humming tunes new and old-Scottish, Irish, German, French, Italian, Russian, and, of course, Japanese.

Mama was not “traditional.” She had great affection for Western culture and clothing. So did Papa. The story books they bought me included Aesop’s Fables and Andersen’s fairy tales. Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella, and Hansel and Gretel were part of my life, as were Robinson Crusoe, Tom Sawyer, Huck Finn, and Robin Hood of Sherwood Forest.

mother at their home

in Tokyo.

After moving to the Tamura estate in Hiroshima, my cousin Hideyuki became my brother-in-residence. He knew little about life in Tokyo. But he was a master climber, a catcher of insects, and an excellent player of marbles and paper pachinko. I learned and practiced his crafts so we could play together. He loved having a playmate.

When Hideyuki was occupied, the vast garden of the estate was at my disposal. There were beautifully shaped pine trees, giant rocks, and stone lanterns. Azalea bushes, flowering trees, evergreens, and maples were laid out so that one was awed by beauty from any vantage point. In the winter, the camellias bloomed in bright red, pink and white, next to shiny green holly leaves with red berries. Early spring brought azaleas of every color, as well as aromatic golden and silver lilacs. Condiment plants grew in shady spots, and a small orchard produced figs and persimmons. Besides birds and insects, there was a variety of stunningly colored lizards and large ground frogs covered with unsightly warts.

Shortly after our arrival in Hiroshima, Papa reported for duty. After basic training, he was assigned to the transport division because of his driving experience from his Nissan days. Despite the patriotic fervor of the time, we were secretly delighted that he had not been assigned to the infantry.

On the morning of father’s departure to the China front, the Tamura clan gathered at Ujina harbor with festive foods and sake. Decanters were filled and emptied quickly. Men sang send-off songs; women filled plates for the men. I was very sad; my Papa was leaving, but no one seemed to grieve. The family congratulated him for having the good fortune to serve his country and his emperor. Afterward, Mama tried to comfort me. But she, too, wept.

Serving the supreme master

News of the declaration of the Greater East Asian War reached our family on December 8, 1941, in the sixteenth year of the Showa Emperor. I was only six years old when the war expanded to include the United States and Britain, and I could understand very little of what was happening. But I sensed that something terribly wrong was taking place, and I knew that I could no longer see American movies, which I loved. “Hush,” I was told. I mustn’t even speak of American movies to others. Papa, who had just come home after serving a tour in China, was called back to the army. He would soon become an officer supervising transportation on the Inland Sea. His headquarters would be in Hiroshima, and he would be able to come home at night.

My school in Hiroshima was the elite Seibi Military Academy, which my father and his brother, Uncle Hisao, had attended. Seibi Academy, run by the Imperial Army in the ancient Samurai tradition, was far more rigorous than public school. It was like an austere military compound, with tall, green poplar trees bordering spacious school yards. The teachers were firm and demanding, but well liked. Inside the school gate was a stone structure like a mausoleum, in which were the Goshinei, the sacred pictures of the emperor and the empress. One was not permitted to walk past it without offering some expression of deepest respect and humility. We were taught to offer our deepest and most reverent bow, the Saikeirei.

That made me think of a day at my school in Tokyo, when the emperor and empress were to pass by. Although we were marched down to the street to greet them, our heads were to remain in the Saikeirei position so that the imperial couple would not see our faces and we could not see theirs. But I looked up anyway and saw the sweet face of our empress. No one else saw her. I had been told that anyone who looked would be blinded. My eyes, however, were not affected.

At the Seibi Academy, both girls and boys rehearsed the military code of honor and the marching routine daily. We paid respect to war heroes and the heroic war dead in every formal activity. On the eighth day of every month, the anniversary of the declaration of war, all of us marched to the Gokoku Shrine. The children whose fathers had died in action lined up in front. As the months and years passed, more and more children joined the line.

Those who had sacrificed their lives with special courage were called Gunshin-military saints. We were taught that the seven men chosen to act as undersea human torpedoes in the attack on Pearl Harbor were Gunshins. No one disputed their dedication, but I wondered why there had been only seven. The men had been allowed to bid farewell to their families; their mothers were said to have been proud to give their sons to their country.

We heard self-sacrifice in the war praised again and again until it made us all feel that dying for our country was most desirable. Although we were children, it gave us a sense of purpose to think that we might die for a cause, the most glorious of which was to die for the emperor. Nevertheless, I could never quite imagine becoming a human torpedo.

Our school days usually began with an assembly. The principal, who stood on a wooden platform a few feet off the ground, issued instructions and announcements. This was followed by rigorous calisthenics performed to lively music from a speaker. As the war progressed, building stamina became ever more important. The drill began to include long-distance running; carrying a partner on our back while marching was also added.

At midday, there was additional stamina building in which we stripped to our underpants so that we could give our bodies wet or dry washcloth rubs for 20 to 30 minutes. Winter and summer, we rubbed our bodies furiously outdoors. The teachers praised us when our skin glowed pink, proof of a job well done. For the older girls, it was embarrassing to stand unclothed on the same lawn with boys of the same age and male teachers. But this was wartime.

Competitive sports were no less important. We had to reach certain goals in gymnastics, short- and long-distance running, hurdles, jumps, vaulting, turning bars, rope climbing, and throwing. Failure was not acceptable. One worked at it until the effort was adequate. The performances were closely timed, recorded, and rewarded. A red badge marked the greatest achievement, whereas blue and brown badges indicated less merit. I earned my red badge after performing 50 front wheels on the bar and nearly fainting from exhaustion. Homework, of course, was compulsory—during school holidays, over the new year, and throughout the spring and summer.

By the winter and spring of my fourth-grade year, the mood of the country began to change drastically. The war losses were slowly coming to light. Japan might not win. My first real sense of grief came when the principal announced at our morning assembly that the troops stationed on Attu Island had committed ritual suicide rather than surrender. We sang for the fallen heroes:

To the sea

A willing corpse in water.

To the mountain

A willing corpse in the thickets.

Never turning back,

As we serve our Supreme Master.

To the mountains

The Tamura children attending the Seibi Academy walked to school together every day. Cousin Hideyuki and Cousin Kiyotsune were beginning to notice pretty girls in school, and I was starting to notice some of their athletic friends. I also admired Kiyotsune’s gymnastic ability. He and I often waited for one another to walk home together, chatting about this and that. Once be beg.an asking whom I really liked, calling out names and asking “yes” or “no.” He saved his name for last. How sweet he was. I never got to tell him how much I admired him.

By 1945, B-29s flew all over Hiroshima prefecture on bombing missions. Tokyo was firebombed, and my Aunt Kimie was burned to death. In Hiroshima, shelters had been dug everywhere, and hurriedly built cement cisterns held water. We were drilled time and again on how to put out fires caused by incendiaries. Air raid sirens went off day and night. All of our clothes had labels sewn in with our names and addresses.

Kamikaze missions were being flown and hailed, but fuel for planes was running low. The draft age was lowered to 17, and children in high school were mobilized to do public labor. Finally, school-age children, in the sixth grade and under, were ordered out of the cities in a mass evacuation. The departure date for the children of the Seibi Academy was April10. We would go to Kimita, a village in the mountains. That was frightening, but at least I would be with my best friend, Miyoshi.

For weeks, Mama worked at her sewing machine, whipping up my clothes, zabuton cushion, and futon. There was a weight limit for how much could be taken, so Mama kept checking the weight of the bundle she was preparing. We went over its contents in detail, but she saved a little pouch for last, which she placed in my hand. “This is part of us,” she said. “Papa’s nail clippings and my hair.”

The Kimita elementary school was a spacious, two-story building. There wasn’t much playground equipment—no factory-built jungle gym, but there was a wooden one, held together by ropes. The 40 Seibi Academy children formed their own groups in the school, but schooling itself became less and less important. In the end, we went to school only on rainy days. Otherwise, we worked outdoors.

The work was beyond our abilities, even after the stamina training at the academy. We dug up giant pine roots, built hearths, and tried to extract pine oil for airplane fuel. Some children wielded shovels; others carried rocks on their backs. Soon, food became scarce, and we were sent out in small groups to collect edible plants. We quickly learned which grasses were edible and tasty, and what mountainside had more curly fern buds.

Bathing was difficult at first. We would work all day and often go to bed dirty. Soon, everyone had lice. We became like a tribe of monkeys, constantly bending over to pick lice eggs out of a friend’s hair. We were ashamed. Eventually, the Seibi group was divided up, and three or four would go to neighboring farmhouses for bathing, once or twice a week. The farmhouses lacked plumbing, and their wells seldom had pumps. We drew the water and built the fires to heat it. But we loved our bathing day, sitting with friends, checking the fire, and talking idly while waiting for a nice warm bath. It was almost like being back in Hiroshima

Our letters home were censored by the teachers, who refused to mail anything that even hinted that we were unhappy. But we were. We were always hungry, and health-related problems, especially bed-wetting, grew worse among the children. Miyoshi and I almost got into a fight one morning when I woke up in a drenched futon after she had slept in my bedroll with me. My underwear was dry, but hers wasn’t.

Miyoshi and I became convinced that our lives were more endangered by staying in the mountains and being hungry and lice-infested. I was having stomach problems and frequent toothaches. We secretly mailed an uncensored letter from the village post office saying that we wanted to come home. On the afternoon of August 4, our mothers came to get us. Miyoshi and I were like a pair of kittens, snuggling up to our liberators. Our mothers suggested we remain another day, just to rest, before going home. But Miyoshi and I were desperate to leave that place, so we returned to Hiroshima August 5. As we went to our separate homes, Miyoshi and I promised to play together again soon.

A waterfall of light

The sun was shining in the garden on the morning of August 6, a Monday. A sense of gratitude welled up in me. I had escaped the countryside. No more mad dashes to the cold stream to wash up at dawn. No more heavy rocks to carry on my back. No more lice. No more going to bed amid the muffled sounds of weeping after the lights went out. No more gnawing hunger. I was a child again, held within the protective embrace of my mother and father.

Papa was already working at the harbor when I awakened. Hideyuki was at school. Mama soon went off to join her obligatory work detail, which was tearing down abandoned houses in the town center so they would not provide fuel in the event of an incendiary attack. If possible, she would try to slip away by lunch time so she could spend some time with me.

I lay back on my futon to read a paperback story about a Samurai duel that Hideyuki had loaned me. It was warm and the breeze was gentle. I wore nothing but underpants.

When the air raid warning siren went off at about 7:15, I turned on the radio. The voice seemed casual. Three enemy planes were heading toward the city. It hardly seemed worth worrying about. Hundreds, yes. But three? I remembered the first time planes had flown over in the middle of the night on their way to another city. Paralyzed with fear, I had clutched Mama, asking her, “Are we going to be hit?” She didn’t know. But whatever happened, she had said, we would be together.

About 7:30, the radio announcer said the air raid warning had been canceled. The enemy planes had turned around. It was safe to go outside. I turned off the radio and went back to reading the Samurai story.

About 45 minutes later, an intense duel between rival swordsmen was about to take place in my book when a blinding flash swept across my eyes. In a fraction of a second I looked out the window toward the garden as a huge band of white light fell from the sky down to the trees. Almost simultaneously, a thunderous explosion gripped the earth and shook it. I jumped up and braced myself next to a large pillar, as Mama had told me to do if a bomb hit nearby. Pieces of the heavy clay-tile roof fell about me. It was dark, as if the sun had disappeared in the thick black air and swirling wind. My mother had taught me to “live” if an air raid came-to flee fire, to seek the river. But now, there seemed to be no alternative to death as the earth heaved.

Suddenly, the wind and the motion stopped. The thick air began to clear. I was covered with soot and debris, but alive. The pillar had held, protecting me, giving me a breathing space. I tried to clear a larger space, but the tangled pieces were more than I could handle.

I cried out, and Aunt Fumiko’s faint voice answered. “Where are you, Hideko?” She helped me get out. Although she was battered and scratched, her baby daughter was unhurt. After the flash, she had shielded the baby with her body.

After several loud yells, we found Grandmother Tamano and Aunt Kiyoko. They were bleeding and bruised and moving about aimlessly, as if in shock. Suddenly, we heard Fumiko’s husband, Uncle Hisao, calling for help. He was sitting just outside the rear gate. His torn and blackened shirt was stained with blood and his eyes seemed hollow. He had been cut with flying glass and blood streamed from his throat, where a nail had been driven. He repeated over and over, “Mo Dame da … this is the end, this is the end.” Aunt Fumiko sobbed as she picked out pieces of glass stuck in his skin.

My injuries were minor, a few cuts and bruises and a gashed right foot. I threw some clothes on and then tried to get everyone to leave as quickly as possible. Mama had told me, again and again, that in a bomb attack, fire would follow. But my grandmother and aunts and uncle lay under a tree in the garden and seemed not to hear me as they nursed their wounds. I wanted to cry. Mother had told me not to wait, to escape before the fire came.

Across the street, a medium-sized factory burst into flame and I knew that a wind shift could bring it to the remains of our house. I screamed, “Fire, fire, you’ve got to leave you’ve got to get away!” No one responded. I could not wait. My mother must be obeyed. As I ran from the garden, I kept shouting, “Please leave!”

Running and walking away, I passed neighbors, disheveled and confused. They paid little attention to passers-by; no one recognized me. Their attention was fixed on getting out and looking for members of their own families. Houses had fallen in or were barely standing. Small flames were starting to spread like torches and the wind fanned them into fireballs. I heard cries of people asking for help. But I could respond only to my inner voice, my Mama saying, “Go to the water, child, stay close to the river, save yourself from fire.”

As I headed toward the Ota River, limping and dragging my right foot, more injured people began moving the same way, in the general direction of the city’s outer limits. Their clothes were torn and burned; some were naked or nearly so. I tried to look for someone I might know. There were no familiar faces.

Reaching the river, I saw a small group of adults and children, their hands clasped in prayer. An older man, perhaps the head of a family, directed them to pray for the safety of others left behind. Explosions from the direction of the army base across the river rent the air every half minute or so. “They got the arsenals,” someone said.

Suddenly, someone called my name. It was Noriko, a girl who lived next door. Her face and arms were very red. She had run from the schoolyard of her elementary school and now she was escaping the city with her family.

“Nori-chan, what happened to you?” I said.

“There was a flash and it burned me,” Noriko answered.

“Yes, I saw the flash,” I said. “It was like a white waterfall. Did your school get a direct hit?”

“It must have,” she said.

As we talked, large blisters formed on Noriko’s face and it became so swollen that I could scarcely recognize her any more. She said some of the children were in much worse shape than she, and the teachers were so injured that they could offer no help. She didn’t know what happened to the other children or the teachers. I was grateful that there was a family I could walk with, even though Noriko was in such pain that she had to stop talking.

At the river, we saw a young schoolgirl slowly walking along, with pieces of skin hanging from her arms. Someon said she was trying to cool her burned skin, but as she rubbed water on it, it came off. She cried in pain.

The girl who could not assuage the pain with river water, Noriko’s swollen face, the growing stream of burned and lacerated people, were but grains of sand on a vast beach. The horror was too great for comprehension.

The search

Thanks to a kindly driver who piled refugees into his truck, I made it to the countryside, where I was taken in by a farm family. The next morning, the farmer offered to bicycle into Hiroshima to seek out my family. He knew the Tamura home, one of the grandest in the city. When he returned at day’s end, he said he had found my father at the burneddown house, but not my mother. He learned that Uncle Hisao had been patched up by a surgeon friend. Grandma Tamano and Aunt Kiyoko and Aunt Fumiko were bruised, but otherwise unhurt. Baby Kumiko was fine. We survivors of the Tamura household would meet at the home of a family friend in Kabe township.

The reunion in Kabe was not joyous. My mother was missing as was Hide yuki, Uncle Hisao and Aunt Fumiko’s only son. Although I was an only child, Hideyuki had been like a brother. I adored him. But like a brother, he had terrified me at times.

The Tamuras had a bomb shelter deep in the garden, behind the trees and rocks. Hideyuki was obsessed with B-29s, which were systematically burning Japan’s cities. To Hideyuki, the B-29 was a marvelous work of engineering. When the bombers flew over Hiroshima on their raids elsewhere, he would slip out of the shelter and go up to the roof of the house, where he would stare at them with binoculars. The rest of us would scream for him to come down, but his fascination with B-29s remained undampened. But now he was missing, and we had learned that a single B-29 with one bomb had caused the damage.

After the fires had burned out, we returned to Hiroshima to search for Hideyuki and my mother. Because the injured had fled in all directions and because the center of the city had disintegrated, there were no clues as to where to start. We began by checking out the “rescue” stations-schools, police yards, and temples-where the dying awaited medical care that did not exist.

In the police yard, my eyes were caught by a naked young woman, scantily covered by a thin blue cloth. Her petite body was curled up and she was breathing with great difficulty. A tag pinned to the cloth gave her name. She was a kindergarten teacher from my neighborhood. I tried to ask if she was all right. She whispered, “It is so hard. It is so hard.” Her body began to shake and convulse and then she died. There were no marks on her, no cuts or blood or burns. I could not understand, and I was terrified.

At the next rescue station—a temple—the singed and blackened bodies lay on the floor unattended. The stench of rotting flesh filled the air. Soft moans were the only signs of life.

I called out Mama’s name. It was difficult to think of her lying there, one of those disfigured, helpless people. But I could not bear thinking of Mama dying alone. Calling her name caused people to stir. They asked for water, but I had none. No one did.

At the third rescue station, I decided to sing Mama’s favorite lullabies and melodies, which we used to sing together. I prayed, “Please God, let the wind carry the tune to my Mama.” As I let the wind carry the melody of my soft humming, tears began to roll down my cheeks. But I wept quietly. I did not want the wind to carry the sound of my sobs to Mama, who I was sure was very hurt and dying. Otherwise, she would have returned to us by then.

I did not find Mama at the rescue stations. Uncle Hisao and Aunt Fumiko failed to find Hideyuki. We were told that my friend Miyoshi had died. However, Cousin Kiyotsune was found alive in the front yard of the Red Cross Hospital by his parents. He died a few days later.

We learned that most of Hideyuki’s friends from the Hiroshima First Middle School were either dead or missing. Many had been crushed under the collapsed classrooms while others had been scorched in the melting heat.

Kiyotsune’s mother told Aunt Fumiko, “You may be lucky. You didn’t have to watch your son’s end. You won’t keep on seeing how he had to die.” Tomoko, another of my second cousins and a playmate, never came home from school. She was never found. Her mother went into seclusion for the rest of her life.

One day, one of Hideyuki’s classmates found Uncle Hisao and Aunt Fumiko. The classmate—Hara—had been among the few who escaped the collapsed school. He had fled the fires and joined a crowd moving toward Mt. Hijijama when he saw Hideyuki. Hideyuki was badly burned, naked to his calf girdle and army boots. He walked awkwardly, ghost-like, with his hands raised before him. He told Hara to go on although he could not.

Hara took Hisao and Fumiko to the spot where he last saw Hideyuki lying on the ground. The bodies had been removed. My aunt and uncle asked around if anyone had noticed their son lying there. People said there had been many bodies and the soldiers had hauled them away. No one knew where the bodies had been cremated.

In early September, we learned about Mama. A neighbor had been with her at the moment the bomb exploded. She and Mama were inside a concrete building near the center of the city. Because the neighbor had her two small children with her, and Mama had had a miscarriage in July, they had been excused from having to do the laborious outside work.

They were just inside the entranceway when the bomb exploded. Mama pulled her straw hat down over her ears and ran inside, just as the building fell in on her. The neighbor stayed in the entranceway and covered her children. She escaped before fire consumed the building.

My father went to the ruins of the building. There were several remains, so he could not tell which had been his wife. Then he stumbled upon an army canteen he had loaned her. Next to it were half-burnt, half-weathered remains.

He brought Mama’s ashes home in his army handkerchief. I begged him to take me back to the place where he had found her. He refused. It was not a sight for me to remember, he said. To this day, I ask myself, “Was she crushed instantly?” I pray that she was.

By the river’s banks

More than 23 years after the bombing, Papa traveled to Chicago to be at my wedding. Over the years, we had seldom spoken of the unspeakable past. But on that trip, he shared something with me that I had never heard before.

He had been at his post at the harbor, more than two miles away, and he had been well shielded by a sturdy building when the bomb burst. A few hours afterward, he had encountered a young American prisoner of war wandering in a daze. The young man looked no older than 17, with blond hair and blue eyes, and was naked except for his boxer shorts. He was surrounded by a crowd of injured civilians, mostly old men and women, carrying stones which they were about to use against him. My father, speaking as an army officer, reproached the otherwise ordinary and peaceful citizens. The young American, he said, was a prisoner under the protection of the military. He was not armed and he was obviously not about to harm anyone. They must not become killers themselves.

Later, Papa said, he learned that the bomb had killed 40 to 50 American prisoners of war who were located near the epicenter. As the officer in charge of the clearing task force, he was asked if the bodies of the prisoners should be cremated along with the Japanese. He told the workers that the American soldiers should be granted their own country’s custom, which was to be buried.

By the banks of the Ota River, the Americans who perished in Hiroshima were buried. My father said he often wondered long after the war about the handsome young man with the fearful eyes, and about his parents. They must have grieved for their son, who almost surely never came home. As he spoke, there were tears in his eyes.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Hiroshima, archive75, first person

Topics: Nuclear Weapons