Sure, deter China—but manage risk with North Korea, too

By Ankit Panda | March 10, 2022

Sure, deter China—but manage risk with North Korea, too

By Ankit Panda | March 10, 2022

The military competition between the United States and China will intensify in the coming years. Like the Obama and Trump administrations, the Biden administration sees the Indo-Pacific region as a priority. Unlike its predecessors, however, the Biden administration will likely oversee a more successful recalibration of US capabilities to the region. Having withdrawn from Afghanistan in 2020, the administration has sought to emphasize its Indo-Pacific focus through multiple steps. The new US-United Kingdom-Australia (AUKUS) partnership, the US focus on maturing the “Quad” consultations with India, Japan, and Australia, and efforts to emphasize US support for Taiwan are components of this so-called pivot to Asia, alongside a broader push to augment military capabilities in the region under the aegis of pursuing so-called “integrated deterrence” against China (Lopez 2021).

As the administration pursues its security and military posture goals in Asia, it continues to focus almost exclusively on allies, partners, and China, the main adversary. While this approach covers a wide range of countries, it omits a full consideration of the effects many of these changes are likely to have on the newest nuclear deterrence relationship US military planners are managing: the one with North Korea. Many of the changes to US military posture in the Indo-Pacific being undertaken with China in mind will also weigh on possible Korean Peninsula contingencies; the administration cannot exclude a consideration of these factors as it proceeds.

Such consideration is particularly urgent given that North Korea’s nuclear posture and strategy emphasize nuclear first use, and that Pyongyang has long expressed anxieties about US nuclear and conventional preemptive attack, including on its leadership. Failing to consider these issues as efforts to pursue “integrated deterrence” in the region proceed could open new pathways to nuclear escalation with Pyongyang.

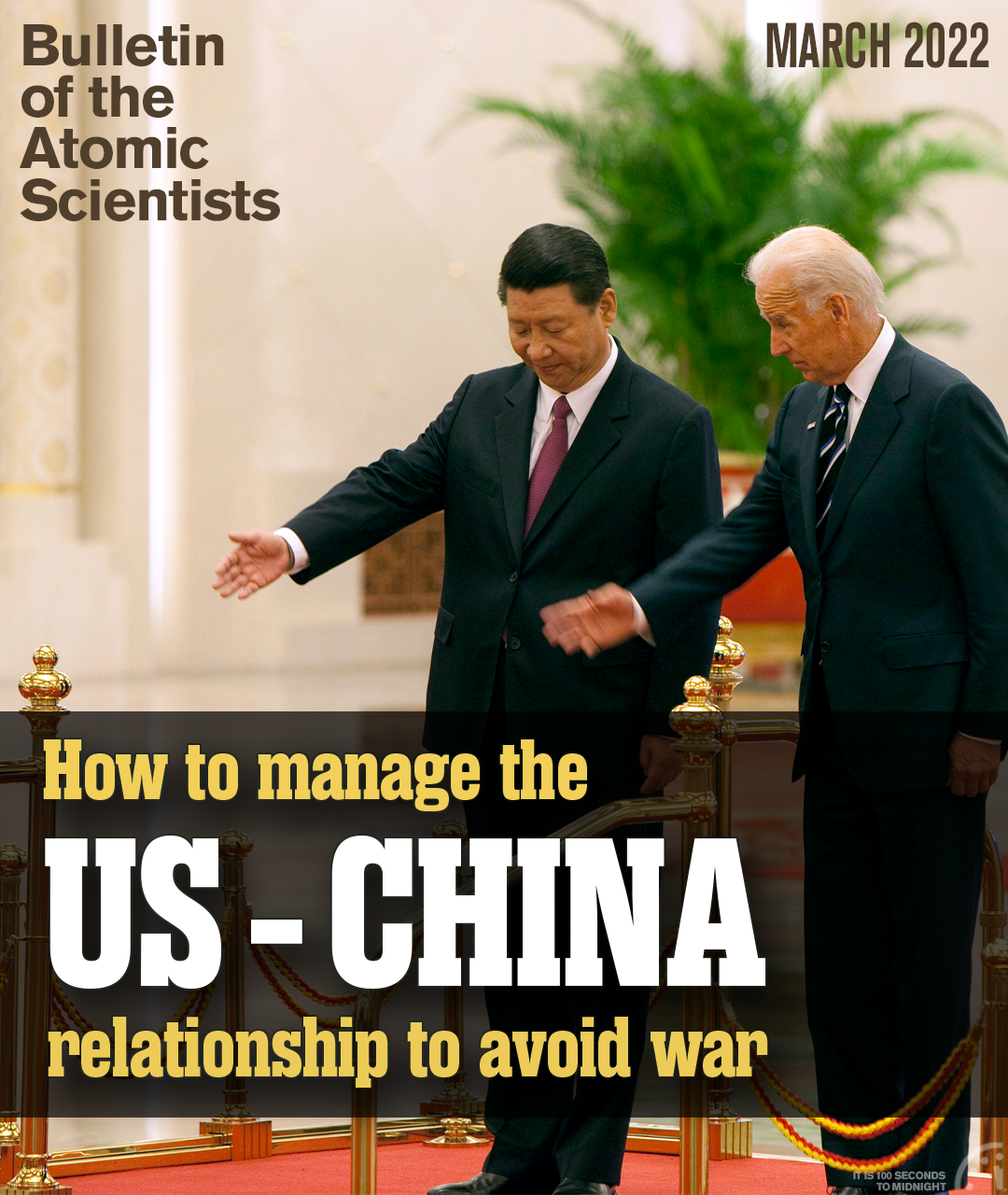

Dual dilemmas in Asia

As it continues to pivot to Asia, the Biden administration has expressed concerns that tensions with China could spill over into conflict—if not by choice, then through miscalculation or misperception. As a result, the administration has underscored the importance of “responsible competition.” During a September 2021 phone call between the president and Chinese leader Xi Jinping, Biden made clear that steps needed to be taken to “responsibly manage the competition between the United States and the [People’s Republic of China],” and that both countries needed to ensure that “competition does not veer into conflict.” This sentiment also permeated Biden’s virtual meeting with Xi in November 2021 (White House Briefing 2021). This time, the president emphasized the need for “common-sense guardrails to ensure that competition does not veer into conflict.”

The overwhelming focus on China has had the effect of relegating what was a more prominent issue for the Trump administration in this part of the world to the relative background. Days before Biden was inaugurated, North Korea’s leader, Kim Jong-un, laid out an ambitious five-year military modernization program at the Workers’ Party of Korea’s 8thParty Congress (Panda 2021a). The plans emphasized, among other objectives, qualitative modernization and quantitative growth in the country’s nuclear forces; Kim’s stated modernization wish list included eyebrow-raising capabilities like hypersonic weapons, which have since been tested, and multiple warhead-capable missiles and tactical nuclear weapons (Wall 2022). These developments took place against the backdrop of North Korea’s continued self-imposed isolation in light of the Covid-19 pandemic, which the country described in January 2020 as a threat to its “national survival” (Hotham 2020). This isolation has manifested in a general disinterest in diplomacy with the United States.

The Biden administration, to be fair, has not ignored North Korea (also known as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, or DPRK). It conducted a policy review in the first half of 2020 and announced its intentions to pursue a “calibrated, practical approach that is open to and will explore diplomacy with [North Korea]” (Panda 2021b). In the months since, the administration’s appointed envoy on North Korea issues, Sung Kim, has emphasized an open-ended interest in meeting with North Korea: “We remain ready to meet with the DPRK without preconditions, and we have made clear that the United States harbors no hostile intent towards the DPRK” (Associated Press 2021). The North Korean response has remained one of disinterest and active resistance. Pyongyang has repeated familiar mantras on what it perceives as a sustained US “hostile policy” that continues under the Biden administration (Smith 2021). Elsewhere, Kim Jong-un has explained what he sees as a prerequisite for change: US “behaviors provide us with no reason why we should believe in them,” Kim said of US assurances and invitations to open-ended talks (Korean Central News Agency/Korea Watch 2021).

For Kim, the difficulty of revisiting diplomacy with the United States remains much the same as it has been since the collapse of the February 2019 Hanoi summit meeting with former President Trump: the US unwillingness to put forward measures such as sanctions relief as concessions for limited North Korean concessions short of total disarmament.

Growing pathways to nuclear use

Kim’s emphasis on “behaviors” relates to longstanding North Korean concerns about US military posture in the region. While Kim and his envoys have never given US officials an authoritative and systematic listing of the capabilities they consider most salient to the “hostile policy,” the list has always placed heavy emphasis on what North Korea considers “strategic assets.” These have included Korean Peninsula- and Japan-based missile defense batteries and their associated sensors, strategic bombers (including bombers based at Andersen Air Force Base on Guam), and attack submarines (Mizokami 2018). As North Korea continues to enhance its nuclear capabilities with quantitative expansion and qualitative refinement, changes to US posture in Asia will be relevant for how Pyongyang thinks about escalation.

North Korea’s nuclear strategy remains predicated on threatening early nuclear use in a crisis (Narang 2017). To offset its immense conventional inferiority against the US-South Korea alliance, North Korea would seek to use nuclear weapons against military targets in the region to degrade the ability of the alliance to sustain an invasion of its territory. While the credibility of Pyongyang’s nuclear deterrent has grown steadily since 2017—the year it first tested a staged thermonuclear device and two intercontinental-range ballistic missile designs—its strategic warning and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities are limited (Roehrig 2017). A consequence of this limitation is that Pyongyang will necessarily have to determine when to use its nuclear weapons based on highly limited information; conventional counterforce threats from the United States and South Korea, meanwhile, will increase pressure further, heightening “use-or-lose” concerns for Kim Jong-un (Long and Green 2014).

This latter issue is the most obvious source of worry today for Pyongyang. South Korea continues to press ahead with an impressively precise array of conventional missile capabilities that—alongside missile defense capabilities—it hopes will be sufficient to limit damage against its territory in a crisis. The United States has supported this development of autonomous capability in recent years—most visibly with the 2021 scrapping of the erstwhile Revised Missile Guidelines, which placed some caps on the range and payload of South Korean missile systems (Panda 2021c). Alongside this, however, the United States is developing a range of new non-nuclear missile capabilities, unconstrained by the 1987 Intermediate-range Nuclear Force (INF) Treaty (Panda 2019), which banned ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500 kilometers (about 311 miles) and 5,500 kilometers (about 3,418 miles). The US Indo-Pacific Command has long viewed a need for new missile capabilities in this range class to offset the Chinese arsenal’s strike capabilities. (China was not a party to the INF Treaty, which was initially a bilateral arrangement between the United States and the Soviet Union.)

While bombers, submarines, and surface ships have given the United States the capability to strike North Korea for decades—and through the lifespan of the INF Treaty—new missile capabilities provide a promptness that was previously only available with nuclear-armed missiles. For example, a Guam-based ballistic missile would endure a flight time in the range of 17 minutes to reach North Korea. These compressed timelines, combined with poor North Korean strategic warning capabilities, could significantly heighten “use-or-lose” pressures for Kim Jong-un—and even raise the prospect of a decapitation strike on him, which would additionally contribute to North Korean willingness to accept risk and consider nuclear use.

Apart from new missiles that are being pursued primarily with China in mind, there’s a need for the United States to revisit signaling practices in the region. For instance, in January 2022, a US Ohio-class ballistic missile submarine made a port call in Guam—the first since 2016 and the second such publicly announced visit since the final years of the Cold War (Lendon 2022). The US Navy, in a statement, noted that the visit demonstrated “US capability, flexibility, readiness, and continuing commitment to Indo-Pacific regional security and stability.” Nothing about this visit appears to have been focused on North Korea, but Pyongyang has previously interpreted port calls by US Navy vessels—particularly what it considers to be vessels with “strategic” capabilities, including aircraft carriers and attack submarines—as threatening. Incidentally, the port call took place after a spate of four missile launch events by North Korea. In a crisis, this type of seemingly disconnected signaling could be misinterpreted and contribute to escalation risks. North Korea, in particular, would have reason to fear the use of US lower-yield W76 mod 2 nuclear warheads deployed on Ohio-class submarines.

A related challenge stems from qualitative features unique to emerging strike systems. In particular, as the United States proceeds to develop and eventually deploy hypersonic weapons, including the US Army’s ground-launched Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon and the Navy’s ship-launched analog, the issue of what has been termed destination ambiguity could loom large in crises with North Korea (Bunn and Manzo 2011). In short, because (unlike most ballistic missiles) hypersonic weapons are capable of substantial post-boost maneuvers, a US launch in a conflict with North Korea would necessarily keep Chinese decision-makers on edge, given that an in-flight maneuver could offer a capability against China-based targets. These concerns would grow should US-China tensions be high in the moments preceding a major Korean Peninsula crisis—as they likely would be. Developing new channels to assure Chinese leaders of US strategic intent in Korean Peninsula-specific crises could help reduce the chance of inadvertent conflict.

China-North Korea coordination

Following a general chill between 2013 and 2017, Sino-North Korean relations steadily improved following Kim’s first meeting with Xi in March 2018. In July 2021, the two countries reaffirmed their otherwise little-discussed 1961 friendship treaty, which includes a mutual defense clause (Jung 2021). Elsewhere, Chinese officials have called on the United States to take heed of North Korea’s “legitimate concerns” and even supported a proposal for sanctions relief alongside Russia (Chung 2021). For Pyongyang, the emergence of so-called great power competition has served as an opportunity to renew deepened political ties with Beijing—even as North Korea doesn’t fully trust China.

The prospect of opportunistically hewing to superpowers for benefit isn’t new to North Korea. Kim Jong-un no doubt appreciates how his grandfather managed the aftermath of the Sino-Soviet split during the Cold War, which yielded considerable dividends from Pyongyang as both Beijing and Moscow offered a range of assistance to North Korea. While North Korea may be a ways off from operationalizing a similar diplomatic strategy between the United States and China today, Kim is not likely to willingly jeopardize continued Chinese and Russian support at international forums like the United Nations. This alone is likely a major consideration for North Korea in deciding when to return to testing intercontinental-range ballistic missiles and possible nuclear weapons—should further nuclear testing be required for the development of more compact tactical nuclear weapons (Panda 2021d).

Both Beijing and Pyongyang have a shared interest in pushing back against the United States as it deploys new capabilities to the region. From US and allied missile defense capabilities to conventional precision-strike systems, each country sees a common set of threats. When North Korea was less sophisticated in its own capabilities, Chinese thinkers saw the United States using Pyongyang as a useful excuse to bolster military capability in Northeast Asia. This was most clearly seen in official Chinese reactions to the then-possible deployment of a Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile defense system to South Korea by the United States in 2016. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi described the X-band radar capability that accompanied THAAD as going “far beyond the defense need of the Korean Peninsula” (Irish 2016). Since then, not only have US-China tensions grown, but North Korea’s capabilities have as well. Given the subsequent shift in China-North Korea relations, conditions today appear to favor a substantial longer-term alignment of interests between Beijing and Pyongyang—even if neither side fully trusts the other.

Conclusions

Whether US decision-makers and planners like it or not, the burdens of the still immature nuclear deterrence relationship between North Korea and the United States cannot be ignored to go all-in on the pursuit of “integrated deterrence” in the Indo-Pacific vis-à-vis China. Over time, as it becomes clear that North Korea’s total disarmament cannot be realized in an acceptably short timeframe, US policymakers might find the prospect of talks concerning nuclear stability with Pyongyang palatable—and North Korea may reciprocate.

But as long as North Korea’s pandemic-induced isolation persists and its capabilities continue to grow, the two countries are left to manage their differences without much in the way of direct communication. Because Pyongyang’s approach to nuclear deterrence hinges on the manipulation of risk—and the acceptance of higher levels of risk in crises—the onus will largely fall on the United States to posture its forces in Northeast Asia and the broader Indo-Pacific to best deter North Korean coercive acts against South Korea and Japan below the nuclear threshold, while minimizing the risks of unintentional or inadvertent nuclear escalation.

It’s not clear that this objective can be fully realized while pursuing the full-range capabilities that are currently planned for development and deployment in the region to deter China. If nuclear and conventional deterrence in Asia are to become truly “integrated,” the US Defense Department should consider not only the full range of capabilities in its toolkit—and the full range of US allies and partners—but also the full range of adversaries whose decisions are likely to affected. In Asia, this includes not only China, but North Korea.

It may not be possible to satisfactorily optimize for the two overlapping problem sets facing U.S. planners here. But, for starters, the Defense Department—specifically, the under-secretary of defense for policy—should undertake a study of how new capabilities, particularly conventional precision-strike systems, deployed to the Indo-Pacific may bear on Korean Peninsula contingencies. Further, the Department should seek to clarify how new capabilities might contribute to Korean Peninsula contingencies—if at all—to the maximum extent possible. Minimizing ambiguities around intent can minimize the space for serious misperceptions with North Korea in a crisis.

As long as North Korea remains in possession of nuclear weapons, the United States will have to bear some risk of nuclear escalation with Pyongyang. At the same time, it should be a priority for US policy makers to ensure that these risks do not grow unnecessarily. As the United States translates a now-decade-long ambition to “pivot” to the Indo-Pacific into reality focused primarily on China, it cannot ignore North Korea.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.