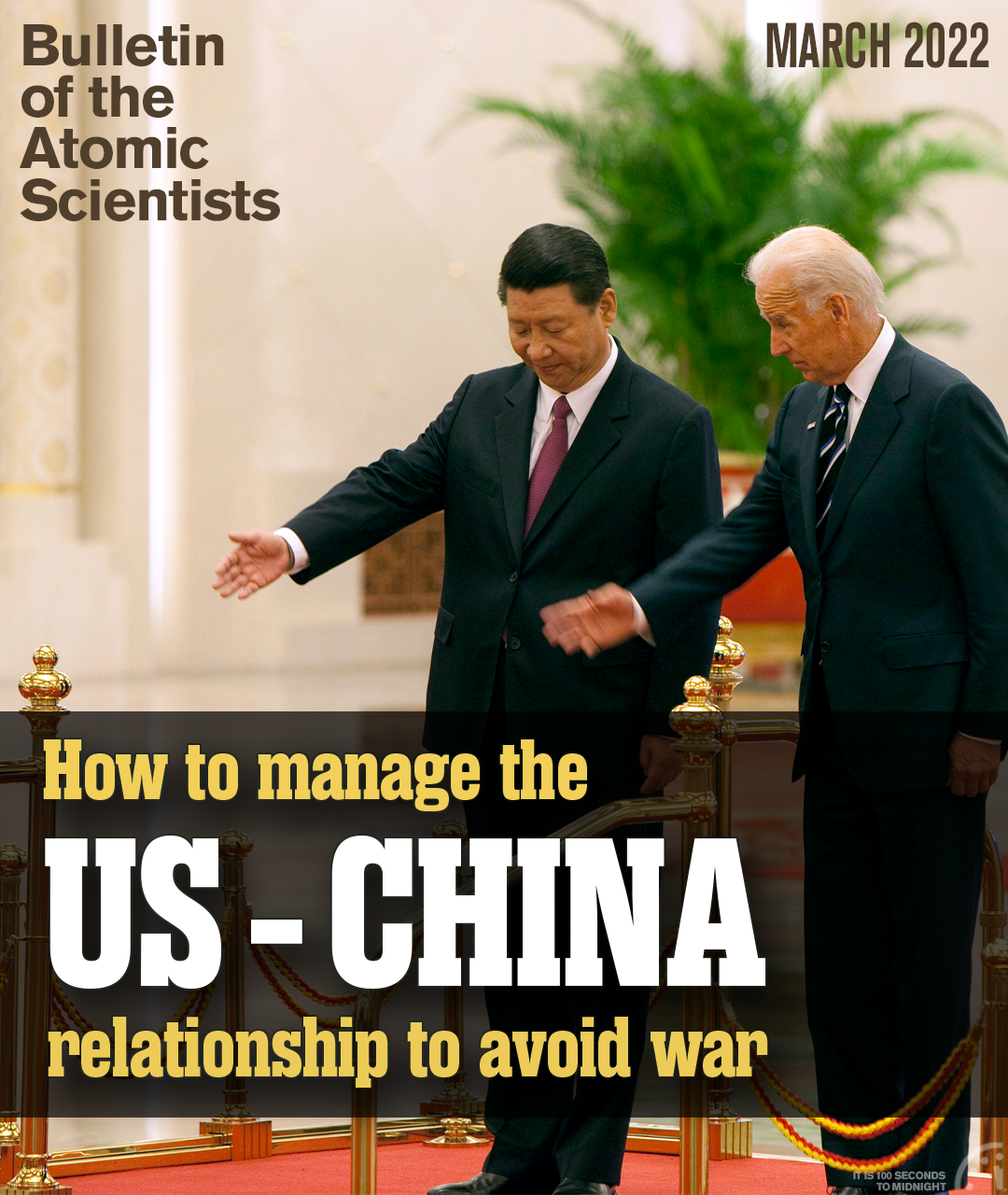

China and the United States: It’s a Cold War, but don’t panic

By Robert Daly | March 10, 2022

China and the United States: It’s a Cold War, but don’t panic

By Robert Daly | March 10, 2022

What is the nature of relations between the United States and China?

Hundreds of attempts to answer this question have been offered over of the past few years. The results have been both serious and silly, as analysts often conflate their desire to guide policy with their hope of coining a catchphrase that lands them in the history books. Most attempts to wed the needs of grand strategy and the methods of marketing have coalesced around the issue of whether the United States and China are now engaged in a Cold War.

The phrase is hard to resist. Bernard Baruch’s 1947 neologism invoked the gravity of the world wars and honored Churchill’s dictum that “short words are best, and old words when short are the best of all.” Today, Cold War captures our sense, and fear, that the United States and China are in for a decades-long, high-stakes, high-cost contest that will reshape the world, affirm or discredit our values, and that can be won, if the United States is wise or lucky, without fighting.

Until recently, most analysts of US-China relations have rejected the Cold War framework, for two reasons.

The first is that China, unlike the Soviet Union, is not merely a military power. Its vast consumer market, its status as the world’s greatest trading nation, its skill in leveraging its wealth to elicit deference and provide public goods worldwide, and its desire to shape the global order make China something the United States has not faced before: a true peer competitor. Because China will be harder to deal with than the Soviet Union, the argument goes, calling bilateral competition a Cold War might deceive Americans into thinking that victory can be won using the old playbook.

The second common reason for rejecting a Cold War framework is that China and the United States are integrated with—even dependent on—each other, while the United States and the Soviet Union were estranged. Deep commercial, institutional, and personal ties—and the need for Beijing and Washington to cooperate to solve transnational issues—all speak against the blanket hostility suggested by a Cold War framework.

Both points are well taken. And there are broader grounds for objecting to a Cold War banner. US-China relations are complex, while Cold War binaries are reductive. It seems unimaginative, and a bit pathetic, to resurrect a 20th century shorthand for a dynamic, multifaceted 21st century phenomenon. Haven’t we moved beyond that? Have we learned nothing? And why invoke martial metaphors at all? Casual use of phrases like Cold War, Tech War, Trade War, and even dodges like “Hot Peace” (Jisi 2022) numb people to the nature of real war and posit as enemies countries with which the United States merely has manageable frictions. Loose talk of war, even metaphorical war, builds support for expanded military budgets and brinksmanship and blinds policy makers to the powers of diplomacy, engagement, restraint, and joint problem solving to defuse tension.

For all of these reasons, American policy makers and issue experts have resisted a Cold War framework. Beijing also adamantly eschews Cold War language in its public pronouncements—even as it prepares urgently for a Cold War.

But issue experts don’t decide which phrases catch fire; the media and the public do that. Use of Cold War is on the rise despite all warnings. Some form of the phrase—Cold War II, Second Cold War, New Cold War, US-China Cold War—seems sure to become the default description of US-China relations over the next year or two.

Cold War assumptions, moreover, are already guiding policy. Structural factors in US-China relations and decisions taken by leaders in both countries have pushed bilateral affairs in that direction. In November 2019, Henry Kissinger warned that the United States and China were in “the foothills of a Cold War” that could end in a conflict worse than World War I.

Two years, one pandemic, a change of American administrations, and a brutal war in Ukraine later, the relationship is above the foothills and nearing the summit. Cold War framing, which I believed was dangerous one year ago, now seems inevitable. This is tragic, but the phrase has the virtue of focusing our attention.

How matters lie

Before christening the new era, it is necessary to take stock of where relations stand. The question is whether Cold War is an accurate description of Sino-US relations; it is certainly not a prescription. No sane Chinese or American wants to go down this road. But…

- The United States and China are competing to shape security architectures, trade and financial regimes, the development, marketization, and regulation of technology, global norms and practices, and the values that underlie them, worldwide. Neither country believes it can create a unipolar world such as the United States enjoyed between the end of the first Cold War in 1991and 2011, but each is determined to maximize its own influence and prevent the other’s dominance.

The competition is unfolding on every continent, at both poles, in cyber space, and in outer space. China still publicly rejects claims that the relationship is competitive, as its diplomatic tradition does not comprehend contests among equals who are not outright enemies. But Chinese scholars have adopted the competitive framework, and its leaders, who have been competing with the United States for decades, are slowly catching up. The General Secretary of China’s Communist Party (CCP), Xi Jinping, uses “The New Situation” (新形势) to describe China’s international challenges—tacit recognition of a more contentious world.

- China’s rapid military buildup, including the expansion of its nuclear forces, reflects the determination of Xi Jinping, General Secretary of China’s Communist Party (CCP), that his country’s armed forces be “commensurate with China’s international standing.” The phrase is vague, but viewed in light of Xi’s 2017 claim that China would “take center stage in the world,” (Gracie 2017) it must be read as indicating a desire to achieve eventual parity with the United States. This is not surprising. China is doing what any large, newly wealthy state in a rough neighborhood would do: pushing its defensive perimeter outward, protecting what it views as its sovereign territory, and trying to make the global environment more amenable to its ends.

As the world’s largest military spender and arms exporter (BBC Business 2021), and with the second-largest nuclear arsenal and close to 800 military bases in 70 countries, the United States is on shaky ground when it criticizes China’s buildup. But America would be foolish to ignore China’s development of a nuclear triad and hypersonic delivery systems, its establishment of a rocket force and space weapons, its construction and militarization of islands in the contested South China Sea, its military coercion in the Western Pacific and South Asia, its intimidation of Taiwan, its development of overseas bases and dual-use ports, its joint exercises with Russia, its theft of American military technology (Fuhrman 2021), its relentless worldwide cyber-attacks, and its belief that it has been contained and humiliated since 1840. Mutual Assured Destruction redux is clearly around the corner.

- Global competition and irreconcilable interests in the Western Pacific have brought mutual distrust to a post-Cold War high. In 2021, 76 percent of Americans (Silver, Devlin and Huang 2021) held negative opinions of China and at least 62 percent of Chinese felt the same way about the United States (Kuo 2021). Mutual dislike has been driven by the trade war, COVID-19, China’s bellicose propaganda organs, and equally bellicose statements from members of the Trump administration and Congress.

China and the United States are alienated from each other not only at the official level, but socially and institutionally. Interactions between the countries’ universities, non-governmental organizations, creators, and tourists had declined before COVID and have slowed to a trickle since. There will be no renaissance of exchanges when the pandemic ends. Americans are wary of China. China’s record in combatting COVID has taught the Communist Party that authoritarianism, isolation, and surveillance work. Xi Jinping will double down on all three fronts in his third term.

- Because of these forces, mutual hostility is becoming an organizing principle across China and the United States. The Chinese Communist Party has always had a defensive posture toward the United States. Under Xi Jinping, this antagonism became deeper, more explicit, and more aggressive. When Xi founded a National Security Commission in 2013, he named Western values as a threat to Chinese security on a par with terrorism and separatism. In the same year, he issued Document 9, a Communiqué on the Current State of the Ideological Sphere, which listed seven “false ideological trends, positions, and activities” that could not be discussed or promoted in China (Creemers 2013). These included Western constitutional democracy, the idea that universal values existed, and Western models of journalism. As Xi’s power grew, he was able to enforce opposition to the West through party cells in corporations, colleges, think tanks, and media.

Across the Pacific, Donald Trump’s 2017 National Security Strategy named China as the United States’ greatest strategic challenge (TrumpWhiteHouse Archives 2017). The US Justice Department has launched The China Initiative (2018) to investigate Chinese espionage and intellectual property theft on American soil (the formal Initiative ended in early 2022); 243 bills treating aspects of China policy have been introduced in Congress; the Biden administration has echoed and amplified Trump’s view of China as a strategic competitor; Biden’s Defense Department has affirmed that China is its “pacing challenge,” (meaning the primary driver of budgets and weapons programs); and the CIA has instituted a new mission center focused on China (Vergun 2021). Every federal agency with an international mandate contributes to what FBI director Christopher Wray calls a “whole-of-society response” to China (Redden 2018). US local governments, campuses, and professional associations have come under pressure to align their China policies with Washington’s. While there is still interest in engaging China throughout the country, Americans are more mobilized against Chinese influence operations now than they were against Soviet efforts during the Cold War.

- The United States and China are competing in the realm of ideas. As Hu Shuli, then editor-in-chief of China’s Caixin magazine wrote in 2013 (Shuli 2013):

America’s policy in Asia is founded not on economics, but on a vision of a secure and stable strategic order in the region. That this vision of a common good—coupled with the values that America likes to champion—is attractive to countries in the region is unsurprising. Thus, in some sense, the Sino-US rivalry is really one fought on values… This is nothing short of a competition between the American Dream and the Chinese Dream.

In an October 2021 press conference (Sanger 2021), President Biden described Sino-US competition as “a battle between the utility of democracies in the 21st century and autocracies.” There are problems with the Biden formula—a critique of the democracy versus autocracy theory lies outside the scope of this essay—but there is no question that the United States and the CCP have different theories of human flourishing and incompatible approaches to governance. The United States continues to espouse individual rights, political pluralism, and the legacy of the Enlightenment. Xi Jinping has never articulated his vision in detail—he prefers blandishments like “community of shared future”—but his ideas can be divined from his actions. His view is that his subjects, and all people, exist as homo economicus—beings who can and should be satisfied when their physical, material, familial, and recreational needs are met. Political participation and freedom don’t enter into it. His version of personhood slices off the top layers of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs—self-actualization and transcendence—and gives responsibility for providing the rest to an all-powerful, purportedly benign, self-perpetuating political elite. For Xi, the competence China displayed in enriching its citizens and combatting COVID proves that it has the wisdom to lead the world, while America’s political chaos is evidence of its terminal moral bankruptcy.

- Last, China and Russia are both strengthening their alliance and partnership networks in opposition to each other. President Biden’s vigorous outreach to allies and Xi Jinping’s and Vladimir Putin’s declaration of a strategic bond “without limits” on February 4 clarified the blueprint for 21st century animosities. The war in Ukraine is carving it in stone.

The world’s two most powerful nations have embarked, wittingly or otherwise, on a comprehensive competition, including a contest to shape global order. Their rivalry includes a burgeoning arms race and expanding nuclear capability. Their people are increasingly alienated from each other. Mutual antagonism has become an organizing principle in both societies. Both sides, furthermore, believe that this unpleasantness is all the other side’s fault, and neither seems committed to finding diplomatic solutions. Each believes that any concessions it makes would embolden, not placate, the other, and neither country is willing to reconsider its beliefs or behavior to lower tensions. The likelihood of a catastrophic collapse in relations—that would, for example, see all American corporations in China and all Chinese students in America return to their home countries—is increasing. We are one crisis away from cementing rivalry as the basis of bilateral relations for decades to come.

Finally, there are no true bright spots in the relationship—no model of successful management of one sphere of relations that might be applied to the relationship as a whole. Beijing and Washington have already flunked the alien invasion test. Their inability to cooperate in the face of acknowledged existential threats to the health of the planet is the most depressing feature of this depressing litany.

If this isn’t a Cold War, the term has no meaning.[1]

Cold War with Chinese and American characteristics

We don’t know precisely what the tastemakers, or whoever decides these things, will call this Cold War. We should disqualify Cold War 2.0 for its frivolity and the implicit suggestion that we are dealing with an upgrade.

My preference is Cold War II, pronounced with the same stresses as World War II, to remind us (1) of the destruction this rivalry could wreak if it turns hot and (2) of continuities between the 1947-1991 contest and the one that began in 2012. Just as many historians now view the two world wars as a single conflict with a long intermission, we should see the two Cold Wars as related phases in the evolution of world order in the post-colonial and global eras.

But continuities should not be overemphasized. There are factors unique to the Second Cold War that will shape its prosecution and outcome:

- Multilateralism, and what Fareed Zakaria called “The Rise of the Rest,” mean that neither China nor the United States can aim for the kind of complete victory that the United States achieved in Cold War I. Allies, partners, and opponents, with shifting degrees of commitment to both powers, now have experience, tools, and agency that they did not have in the mid-20th century. This will enable them to modify and frustrate the strategies of both major powers in Cold War II. Multilateralism will speak against the formation of blocs and may involve both great powers in networks of compromise that deter aggression.

- Unless there is a military conflict, the legacy of 40 years of Sino-US engagement will put a floor under mutual hostility. Engagement will not cease altogether. Despite downward trends in public opinion, Chinese and Americans have come to know and like each other too well for distrust to devolve into hatred. Chinese-Americans, who may face increased suspicion in Cold War II, will also play a key role in keeping lines of kinship and communication open and in reminding both sides—the United States in particular—of the historical benefits of openness and interaction.

- The legacy of the first Cold War will also inform conduct in the second. The world has done a version of this before: We have analyzed errors, institutionalized successful practices, and socialized distrust of the propaganda and motives of major powers. Nations are no wiser than they were in the second half of the 20th century, but, as Cold War veterans, they are better equipped to resist traditional Cold War tactics.

- China and the United States will both be distracted from rivalry by the large number of epochal changes whose simultaneous emergence is the distinguishing feature of the age. The Rise of China is transformational—it compels us to reconsider our geopolitical assumptions—but we are also confronted with equally great challenges in other arenas: global warming and the loss of biodiversity; the globalization of supply chains, pathogens, crime, ideas, information, economic disparity, and population flows; the emergence of new technologies, like synthetic biology and genetic engineering; and, on a longer timetable, revolutions in gender roles and patterns of belief, including rising rates of secularism and religious extremism, that will reshape societies.

- We faced nothing of the kind in Cold War I. It’s as if the rise of the United States, the little ice age, the extinction of the dinosaurs, the invention of moveable type, the Reformation, the Gilded Age and Great Depression, the Black Death, the Industrial Revolution, and the discovery of the germ theory of disease all appeared worldwide in a 50-year span. Due to the concurrence of these epochal shifts, managing US-China competition—which is the world’s greatest geopolitical challenge—may not be the greatest challenge we confront. The United States and China will face pressures to compromise and cooperate during the Second Cold War that the United States and Soviet Union did not experience during the first. Meeting these challenges, moreover, will limit the resources and attention that Washington and Beijing can dedicate to their competition.

- While the stakes of Cold War II are high, full-bore strategic rivalry may never gather steam due to both nations’ domestic fragility. Political polarization and international perceptions of its failures and unreliability cripple the United States as a global actor. China is constrained by geography and by a number of intractable problems, any one of which could force it to curtail its global ambitions and turn inward: corporate and government debt; an aging population and insufficient social safety net; corruption; pollution of air, water, and soil; the water shortage in the north; stark economic disparities; global resistance to Chinese influence; and a sclerotic political system that is out of step with a modern populace. While these weaknesses might cause either country to lash out at the other to build popular support, they could also convince leaders to make accommodations in the future that they would not consider today.

In the opening sentence of Diplomacy, Henry Kissinger wrote that “in every century there seems to emerge a country with the power, the will, and the intellectual and moral impetus to shape the entire international system in accordance with its own values.” Many Chinese would read that line as an anointing of the People’s Republic of China for the 21st century. They would be wrong. While China has the will to shape the international system, its power is uncertain, and its intellectual and moral preparation is non-existent to insufficient. The United States is still the world’s most powerful nation, but it must undergo a protracted and uncertain healing process before it is fit to reassert itself globally.

How does it play out?

These checks on superpower ambition will not make Cold War II a Cold War Lite. The risk of conflict is increasing, especially in the Taiwan Strait and South China Sea. Even if conflict is averted, major participants in Cold War II, including Russia and America’s allies, will spend trillions of dollars on weapons instead of improving human welfare, and they will prioritize national interests, real and imagined, over meeting common challenges. But the forecast is not entirely bleak. It is likely, for reasons noted above, that American and Chinese citizens will interact more in Cold War II than did their Cold War I predecessors. Rivalry will be pervasive, but not all-encompassing. There will be scope for engagement and, if we have the fortune to muddle through this rivalry, most Chinese and Americans may live their lives largely unaffected by specters that haunt the professional Cold Warriors. Remember them? You will.

Cold War II may not be winnable, but it can end. That will happen when one or both countries cease to see the other as a major threat to its interests, either because the opponent’s capabilities and intentions have altered, or because interests are reconceived. The key factor is change. A Cold War is a play for time—the time required for change to occur, or be induced, in one country, in both, or in external circumstances. When either side believes it is out of time, the war turns hot.

Because US-China rivalry is rooted in conflicting interests and in each country’s beliefs about its role in the world and what people and nations are, change will not come quickly. Unsurprisingly, each country prefers that the other do the changing. Instigating change within the rival nation therefore will be the goal of each nation’s policy. Over the coming decades, the United States and China will strive to change each other—overtly, through negotiation; gradually, through trade, soft power, and adjustments to the international system; and covertly, through a variety of tactics. Some of these approaches may yield fruit. Most will increase enmity. Beyond that broad prediction, the course of the struggle cannot be foreseen.

One recommendation: Both sides should manage Cold War II within a framework that promotes multilateral efforts to combat the transnational threats noted above—climate change, pandemics, technological disruptions, and economic injustice. If Beijing and Washington cannot temper their hostility enough to do that, then both are very far gone, and neither will have the prestige to lead the global system.

Endnotes

[1] One common counter argument is that Sino-US trade in goods and services remains high, and American investment in China is increasing due to the liberalization of Chinese financial policy. This is true, but both countries continue to decouple vital industries and, in contrast to the period from 1992 to 2012, when, as Xi Jinping put it “economics was the ballast of the relationship,” security concerns now drive economic policies in both countries. It is not impossible that economic interdependence will yet stabilize relations, but, for now, this objection to accepting a Cold War framework for US-China relations belongs down here in the endnotes.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Cold War, US-China Relations, World Order, second Cold War

Topics: Analysis, Nuclear Risk

Cold War analysis by Kissinger institute guy. The purpose of this article eludes me. Apparently we are locked into an entrenched Cold War with China, and there is no getting out- the last paragraph says it is highly unlikely. So, it offers no paths to peace, no new insights, makes sure that every action of US and China through a Cold War lense. It is the profit model that has sustained our increasing war budget for the past 70 years. Job security for all the war hawks, for all the Kissinger Institute theorists, for all the publications that promote hawkish… Read more »