Nuclear Notebook: How many nuclear weapons does Russia have in 2022?

By Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda | February 23, 2022

Nuclear Notebook: How many nuclear weapons does Russia have in 2022?

By Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda | February 23, 2022

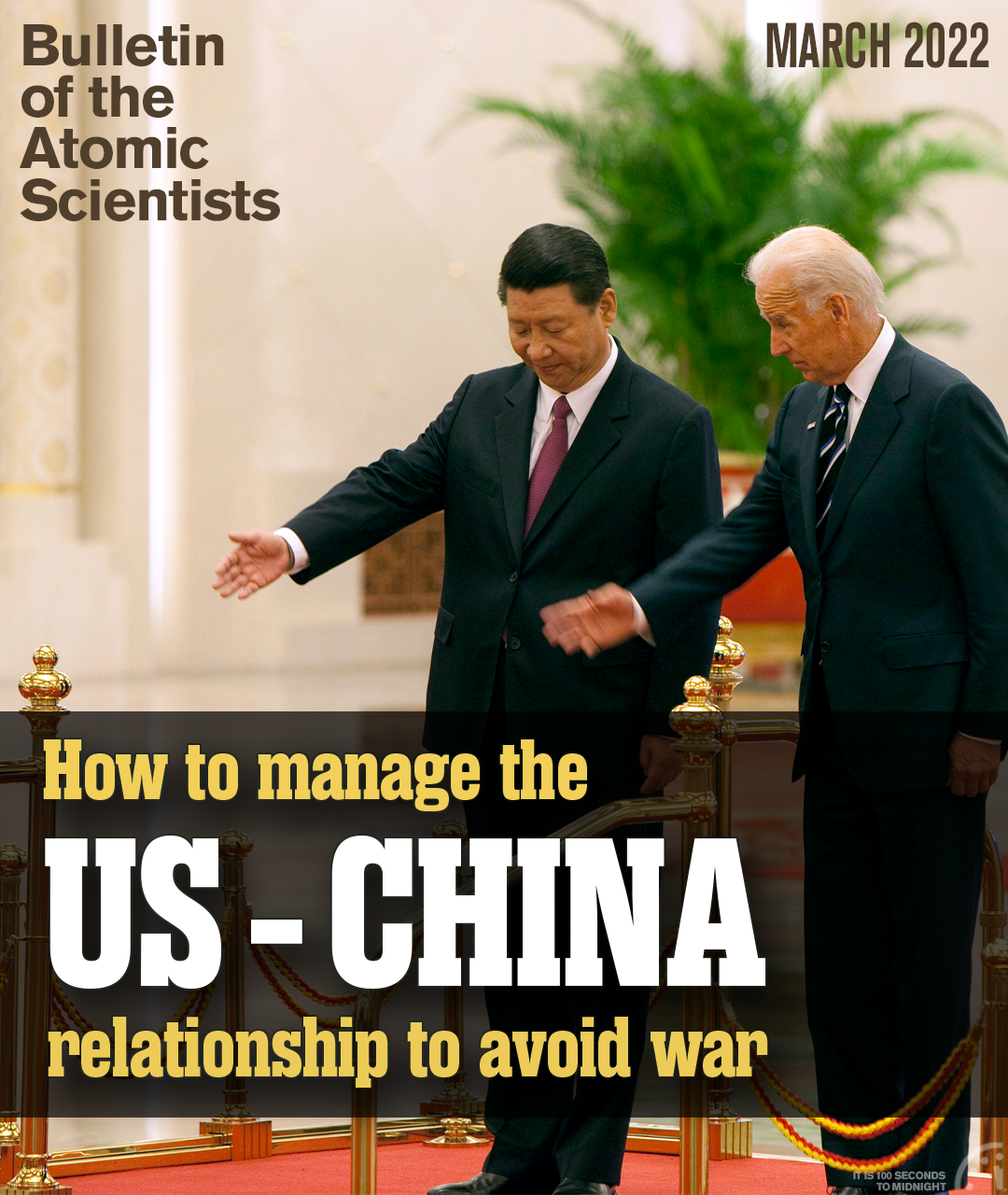

Editor’s note: The Nuclear Notebook is researched and written by Hans M. Kristensen, director of the Nuclear Information Project with the Federation of American Scientists, and Matt Korda, a senior research associate with the project. The Nuclear Notebook column has been published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists since 1987. This Nuclear Notebook examines Russia’s nuclear arsenal, which includes a stockpile of approximately 4,477 warheads. Of these, about 1,588 strategic warheads are deployed on ballistic missiles and at heavy bomber bases, while an approximate additional 977 strategic warheads, along with 1,912 nonstrategic warheads, are held in reserve. Russia is continuing a comprehensive modernization program intended to replace most Soviet-era weapons by the mid- to late-2020s and is also introducing new types of weapons. As of February 23rd, 2022, some of the Russian delivery vehicles that are deployed near Ukraine are considered to be dual-capable, meaning that they can be used to launch either conventional or nuclear weapons; however, at the time of publication, we have not seen any indication that Russia has deployed nuclear weapons or nuclear custodial units along with those delivery vehicles. This article is freely available in PDF format in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ digital magazine (published by Taylor & Francis) at this link. To cite this article, please use the following citation, adapted to the appropriate citation style: (2022) Russian nuclear weapons, 2022, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 78:2, 98-121, DOI: 10.1080/00963402.2022.2038907. To see all previous Nuclear Notebook columns, click here.

Russia is in the late stages of a decades-long modernization of its strategic and nonstrategic nuclear forces to replace Soviet-era weapons with newer systems. In December 2021, Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu reported that modern weapons and equipment now make up 89.1 percent of Russia’s nuclear triad, an increase from the previous year’s 86 percent (Russian Federation 2021a; Russian Federation 2020a). The 2021 modernization activities apparently exceeded the projected gains for this year, as President Putin’s 2020 end-of-year address estimated that the modernization percentage would be 88.3 percent by the end of 2021 (Russian Federation 2020a). In previous years, Putin’s remarks have emphasized the need for Russia’s nuclear forces to keep pace with Russia’s competitors: “It is absolutely unacceptable to stand idle. The pace of change in all areas that are critical for the Armed Forces is unusually fast today. It is not even Formula 1 fast—it is supersonic fast. You stop for one second and you start falling behind immediately” (Russian Federation 2020a).

In his 2021 end-of-year speech, Putin also noted that he is “extremely concerned about the deployment of elements of the US global missile defense system near Russia.” In particular, he accused the United States of using its missile defense deployments as a guise to deploy offensive systems targeted at Russia: “The Mk 41 launchers located in Romania and planned for deployment in Poland have been adapted to the use of the Tomahawk strike systems” (Russian Federation 2021a). Officials from the United States and NATO deny that the launchers have been adapted for use of Tomahawk missiles.

Putin also noted his disappointment with the deterioration of the US-Russia arms control regime, and stated that Russia needed “long term, legally binding guarantees […] because the United States easily withdraws from all international treaties, which for one reason or another become uninteresting to them––easily, explaining something or nothing at all without explaining how it was with the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, [the Treaty] on Open Skies” (Russian Federation 2021a).

Russia’s nuclear modernization programs, combined with an increase in the number and size of military exercises and occasional explicit nuclear threats against other countries, contribute to uncertainty about Russia’s long-term intentions and growing international debate about the nature of its nuclear strategy. These concerns, in turn, stimulate increased defense spending, nuclear modernization programs, and political opposition to further nuclear weapons reductions in Western Europe and the United States.

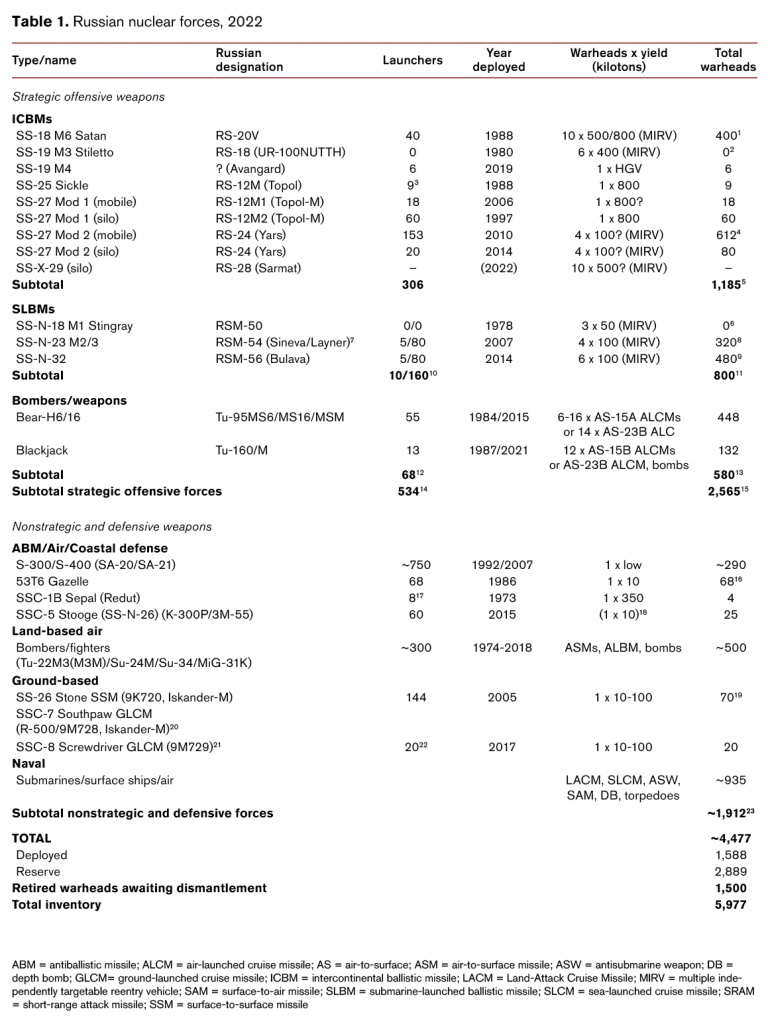

As of early 2022, we estimate that Russia has a stockpile of approximately 4,477 nuclear warheads assigned for use by long-range strategic launchers and shorter-range tactical nuclear forces, which is a slight decrease from last year. Of the stockpiled warheads, approximately 1,588 strategic warheads are deployed: about 812 on land-based ballistic missiles, about 576 on submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and possibly 200 at heavy bomber bases. Approximately another 977 strategic warheads are in storage, along with about 1,912 nonstrategic warheads. In addition to the military stockpile for operational forces, a large number—approximately 1,500—of retired but still largely intact warheads await dismantlement, for a total inventory of approximately 5,977 warheads.1 (See Table 1).

With only two days remaining until its expiration in March 2021, Russia and the United States mutually agreed to an extension of New START that will keep it in force through February 4, 2026. In advance of New START coming into force in 2018, Russia significantly reduced (downloaded) the number of warheads deployed on its ballistic missiles to meet the treaty limit of no more than 1,550 deployed strategic warheads. Russia achieved the required reduction by the February 5, 2018 deadline, when it declared 1,444 strategic warheads attributed to 527 launchers (Russian Federation Foreign Affairs Ministry 2018). The most recent data exchange, declared on September 1, 2021, listed Russia with 1,458 deployed warheads attributed to 527 strategic launchers (US State Department, Bureau of Arms Control, Verification and Compliance 2021a). These numbers differ from the estimates presented in this Nuclear Notebook because the New START counting rules artificially attribute one warhead to each deployed bomber, even though Russian bombers do not carry nuclear weapons under normal circumstances. Additionally, this Nuclear Notebook counts weapons stored at bomber bases that can quickly be loaded onto the aircraft as “deployed.”

Russia (like the United States) could potentially upload several hundreds of extra warheads onto their launchers but is prevented from doing so by the New START treaty limit. The treaty provides an important node of transparency for both Russia’s and the United States’ strategic nuclear forces: as of January 2022, the United States and Russia have completed a combined 328 on-site inspections and exchanged 23,100 notifications (US State Department, Bureau of Arms Control, Verification and Compliance 2022). Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, on-site Type One and Type Two inspections were paused in April 2020. Inspections were set to restart on November 1, 2021 (Post 2021), but that did not happen. The first meeting of the Bilateral Consultative Commission since the pandemic began took place in October 2021 (US State Department, Bureau of Arms Control, Verification and Compliance 2021b).

Due to New START limitations, Russia appears to have been forced to reduce the warhead loading on some of its missiles to less than maximum capacity. We do not know the breakdown of the loading because Russia, unlike the United States, does not publish an unclassified overview of its strategic forces. However, the reduction may have involved scaling back the number of warheads on each SS-18 and SS-27 Mod 2 intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), as well as on each SS-N-32 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM). This demonstrates that New START places real constraints on Russia’s deployed strategic forces. The result appears to be an increased reliance on a strategic reserve of non-deployed warheads that can be loaded onto missiles in a crisis to increase the size of the force––a strategy similar to the one the United States has relied on for several decades.

Russia’s nuclear modernization program is motivated in part by the Kremlin’s strong desire to maintain overall parity with the United States and by national prestige, but also by the Russian leadership’s apparent conviction that the US ballistic missile defense system constitutes a real future risk to the credibility of Russia’s retaliatory capability. Policy and strategy aside, the development of multiple weapon systems, rather than focusing resources on one or two, also indicates the strong influence of the military-industrial complex on Russia’s nuclear posture planning (Luzin 2021).

What is Russia’s nuclear strategy?

The international debate about Russia’s nuclear strategy has reached a new level of intensity, particularly after the Trump administration published its Nuclear Posture Review in February 2018. The Nuclear Posture Review claimed that “Russian strategy and doctrine emphasize the potential coercive and military uses of nuclear weapons. It mistakenly assesses that the threat of nuclear escalation or actual first use of nuclear weapons would serve to ‘de-escalate’ a conflict on terms favorable to Russia” (US Defense Department 2018, 8). Specifically, the document claimed, “Moscow threatens and exercises limited nuclear first use, suggesting a mistaken expectation that coercive nuclear threats or limited first use could paralyze the United States and NATO and thereby end a conflict on terms favorable to Russia.” This so-called “escalate to de-escalate” doctrine “follows from Moscow’s mistaken assumption of Western capitulation on terms favorable to Moscow” (US Defense Department 2018, 30).

The former head of the US Strategic Command, Gen. John Hyten, reacted to “Russia’s destabilizing doctrine on what some call escalate to deescalate” by saying: “I really hate that discussion. I’ve looked at the Russian doctrine. I’ve looked at Russian writings. It’s not escalate to de-escalate, it’s escalate to win. Everybody needs to understand that” (Hyten 2017). Some have suggested that Russian leaders are signaling a willingness to use nuclear weapons even before an adversary retaliates against a Russian conventional attack by “employing the threat of selective and limited use of nuclear weapons to forestall opposition to potential aggression” (emphasis added) (Miller 2015). The implication is that Russia would potentially use nuclear weapons first to scare an adversary into not even defending itself.

Such characterizations conflict with Russia’s publicly stated policy. In June 2020, President Putin approved an update to the “Basic Principles of State Policy of the Russian Federation on Nuclear Deterrence,” which notes that “The Russian Federation considers nuclear weapons exclusively as a means of deterrence.” The policy lays out four conditions under which Russia could launch nuclear weapons:

- “arrival of reliable data on a launch of ballistic missiles attacking the territory of the Russian Federation and/or its allies;

- use of nuclear weapons or other types of weapons of mass destruction by an adversary against the Russian Federation and/or its allies;

- attack by adversary against critical governmental or military sites of the Russian Federation, disruption of which would undermine nuclear forces response actions; and

- aggression against the Russian Federation with the use of conventional weapons when the very existence of the state is in jeopardy” (Russian Federation Foreign Affairs Ministry 2020).

The document’s emphasis on deterrence by punishment, as well as the “defensive” nature of Russia’s nuclear weapons, is likely intended to be a response to the aforementioned US claims of a Russian “escalate-to-deescalate” policy. The updated policy is also consistent with remarks that President Putin made to the Valdai Club in October 2018, when he stated that “Our nuclear weapons doctrine does not provide for a pre-emptive strike.” Rather, he continued, “our concept is based on a reciprocal counter strike … This means that we are prepared and will use nuclear weapons only when we know for certain that some potential aggressor is attacking Russia, our territory” (Russian Federation 2018a). This is additionally consistent with previous iterations of Russian nuclear policy, which has largely remained unchanged since President Putin came to power in 2000 (Russian Federation 2014, 2010). Although some initial reports interpreted Putin’s 2018 Valdai Club comments to mean that Russia might be adopting a nuclear no-first-use policy, this does not seem to be the case; his remarks were more likely meant to respond to the US Nuclear Posture Review’s claim that Russia has lowered its threshold for first use of nuclear weapons in a conflict (Stowe-Thurston, Korda, and Kristensen 2018). Because Putin’s comments imply that Russia would only use nuclear weapons in retaliation against an existential threat, independent analysts have challenged the Nuclear Posture Review’s characterization of the Russian strategy as overblown and a misreading of Russia’s nuclear doctrine.2

Whatever Russia’s nuclear strategy is, Russian officials have made many statements about nuclear weapons that appear to go beyond the published doctrine, threatening to potentially use them in situations that do not meet the conditions described. For example, officials explicitly threatened to use nuclear weapons against ballistic missile defense facilities, and in regional scenarios that do not threaten Russia’s survival or involve attacks with weapons of mass destruction (The Local 2015).

Moreover, the fact that Russian military planners are pursuing a broad range of upgraded and new versions of nuclear weapons suggests that the real doctrine goes beyond basic deterrence and toward regional war-fighting strategies, or even weapons aimed at causing terror. One widely-cited example involves the so-called Status-6—known in Russia as “Poseidon” and in the United States as “Kanyon”—a long-range nuclear-powered torpedo that a Russian government document described as intended to create “areas of wide radioactive contamination that would be unsuitable for military, economic, or other activity for long periods of time” (Podvig 2015). A diagram and description of the proposed weapon, first revealed in a Russian television broadcast, can still be seen on YouTube (YouTube 2015). The weapon, which is under development, appears designed to attack harbors and cities to cause widespread indiscriminate collateral damage in violation of international law.

Intercontinental ballistic missiles

Russia’s Strategic Rocket Force currently deploys several variants of silo-based and mobile ICBMs. The silo-based ICBMs include the SS-18, SS-19, SS-27 Mod 1, SS-27 Mod 2, and the mobile ICBMs include the SS-25, SS-27 Mod 1, and SS-27 Mod 2. In December 2021, Chief of the General Staff Valery Gerasimov declared that 95 percent of Russia’s strategic missile forces are continuously ready for combat use (RIA Novosti 2021a). In December 2021, the commander of the country’s Strategic Rocket Forces, Col. Gen. Sergei Karakaev, stated in an interview with Krasnay Zvezda (“Red Star”), the official newspaper of the Russian Ministry of Defense, that the ratio between mobile and siloed launchers in each regiment is “approximately equal;” however, the number of nuclear warheads assigned to each silo-based missile regiment is “currently somewhat larger” than the mobile regiments because of the siloed SS-18 ICBM, which can carry large numbers of multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs). In total, the ICBMs carry about 60 percent of Russian deployed strategic warheads (Krasnaya Zvezda 2021a).

Based on what we can observe via satellite images, combined with information published under New START by various US government sources, Russia appears to have approximately 400 nuclear-armed ICBMs, which we estimate can carry up to 1,185 warheads (see Table 1). The size of the force that we can observe, however, is difficult to square with statements made by Russian officials. Since 2016, and again most recently in December 2019, Karakaev has stated to Russian news agencies such as TASS that Russia had approximately 400 ICBMs on combat duty (TASS 2016a; Andreyev and Zotov 2017; Karakaev 2019). But since Russia declared 527 deployed strategic launchers in total as of September 2021, a force of 400 ICBMs would mean Russia only deployed 127 SLBMs and bombers, which seems unlikely (US State Department, Bureau of Arms Control, Verification and Compliance 2021a). It is possible that Karakaev is referring to all ICBMs in the inventory (including those in storage), not just those that are deployed. Modernization of the ICBM force also involves equipping upgraded silos with new air- and perimeter-defense systems, and the new Peresvet laser has been deployed with at least five road-mobile ICBM divisions for the purpose of “covering up their maneuvering operations” (Russian Federation Defense Ministry 2019a; Sanders 2021).

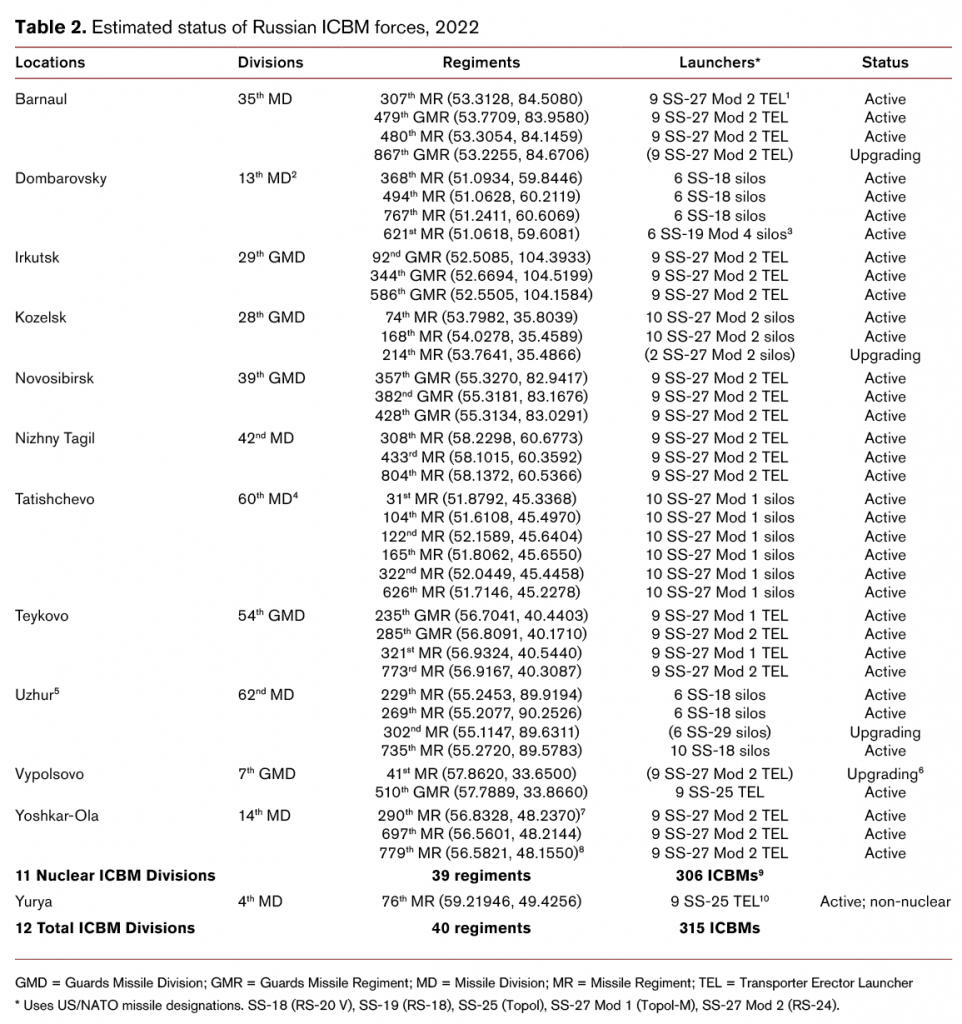

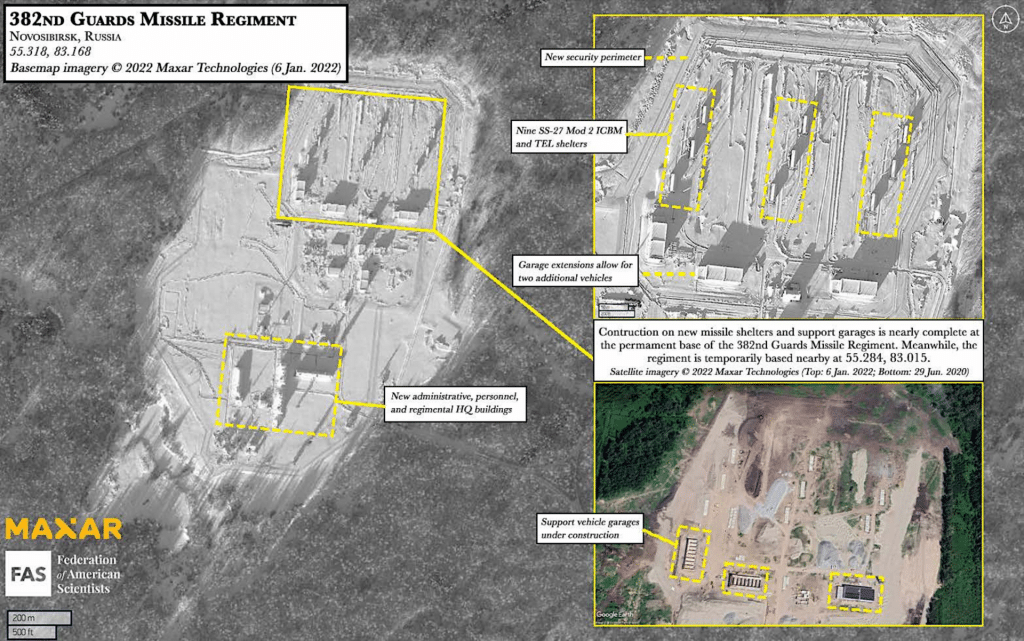

The ICBMs are organized under the Strategic Rocket Forces in three missile armies with a total of 12 divisions consisting of approximately 40 missile regiments (see Table 2). The regiment in the missile division at Yurya operates ICBMs that are believed to serve as a back-up launch code transmitter and are therefore not nuclear-armed. The ICBM force has been declining in number for three decades, and Russia claims to be 83 percent of the way through a modernization program to replace all Soviet-era missiles with newer types by the early 2020s on a less-than-one-for-one basis (Krasnaya Zvezda 2021a). Currently, the remaining Soviet-era ICBMs include the SS-18 and the SS-25. According to Col. Gen. Karakaev, 36 missile regiments are now equipped with modern strategic missile systems––20 of which are mobile regiments and 16 of which are siloed regiments (Krasnaya Zvezda 2021a). However, Karakaev may be including siloed regiments which are currently undergoing infrastructure upgrades to prepare them for future Sarmat deployments. In 2022, Russia plans to place four more missile regiments on combat duty, which will amount to a scheduled increase of 21 launchers: the first SS-X-29 Sarmat regiment at Uzhur, one silo-based SS-19 Mod 4 Avangard regiment at Dombarovsky, and two mobile SS-27 Mod 2 Yars regiments in Vypolsovo and in the Kirov region, possibly at Yurya (Krasnaya Zvezda 2021a; Russian Federation 2021a).

The SS-18 (RS-20 V or R-36 M2 Voevoda) is a silo-based, 10-warhead heavy ICBM first deployed in 1988. It is reaching the end of its service life, with approximately 40 SS-18s that can carry up to 400 warheads remaining in the 13th Missile Division at Dombarovsky and the 62nd Missile Division at Uzhur. We estimate that the number of warheads on each SS-18 has been reduced for Russia to meet the New START limit for deployed strategic warheads. The SS-18 is scheduled to formally begin retiring in 2022, when the SS-X-29 (Sarmat or RS-28) ICBM will begin to replace it at the Uzhur missile field (Krasnaya Zvezda 2021a). Commercial satellite imagery indicates that the 302nd Missile Regiment at Uzhur has already been disarmed in order to accommodate for Sarmat-related upgrades to the regiment’s silos (Figure 1).

The silo-based, six-warhead SS-19 (RS-18 or UR-100NUTTKh), which entered service in 1980, appears to have been retired from combat duty. A small number of converted SS-19s are being deployed with two regiments of the 13th Missile Division at Dombarovsky as the SS-19 Mod 4 with the new Avangard hypersonic glide vehicles (see below). In October 2021, Russian officials announced that the service life of the SS-19 had been extended until at least 2023; this is probably to allow the missile’s boosters to be used for the Mod 4 Avangard deployment (RIA Novosti 2021b).

Russia continues to retire its SS-25 (RS-12 M or Topol) road-mobile missiles at a rate of one or two regiments (nine to 18 missiles) each year, replacing them with the SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24). Eighteen SS-25s were scheduled to be dismantled by November 2022 (Weaponews 2017; RIA Novosti 2020b). There remains some uncertainty about how many SS-25s are fully operational. Garrison upgrades used to involve significant rebuilding, but satellite images indicate that Russia has started to upgrade the garrisons by simply replacing the SS-25s with the new SS-27 launchers and their service vehicles, which are maintained under camouflage nets. We estimate that as few as nine SS-25s remain in the active force, and it is believed that the last SS-25 missile will be removed from service by the end of 2024 (TASS 2021b).

The new ICBMs include two versions of the SS-27: the Mods 1 and 2. We estimate that these two versions now carry more warheads than all the remaining SS-18s. The SS-27 Mod 1 is a single-warhead missile, known in Russia as Topol-M, that comes in either mobile (RS-12 M1) or silo-based (RS-12 M2) variants. Deployment of the SS-27 Mod 1 was completed in 2012 with a total of 78 missiles: 60 silo-based missiles with the 60th Missile Division in Tatishchevo, and 18 road-mobile missiles with the 54th Guards Missile Division at Teykovo. Russian officials indicated in 2019 that the Topol-M units eventually will be upgraded to RS-24 Yars as well.

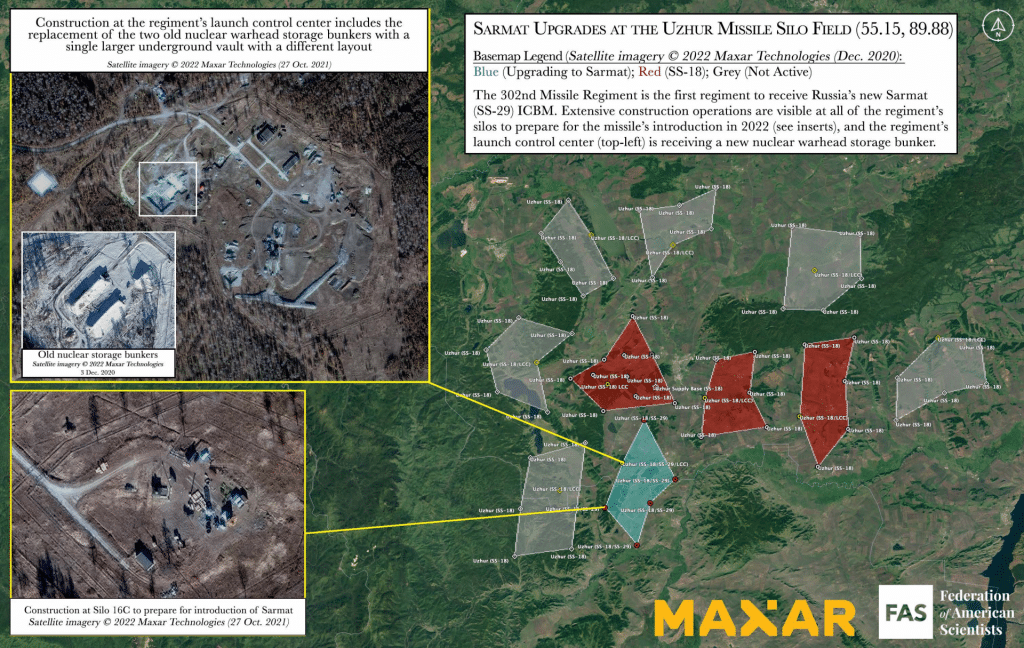

The focus of the current and larger phase of Russia’s modernization is the SS-27 Mod 2, known in Russia as the RS-24 (Yars), which is a modified SS-27 Mod 1 (or Topol-M) that can carry up to four multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs). During an interview with Col. Gen. Sergei Karakaev in December 2020, the Russian Defense Ministry’s TV channel declared that approximately 150 mobile- and silo-based Yars had been deployed by the Strategic Rocket Force (Zvezda 2020). We estimate that as of January 2022, this number has grown to approximately 173 mobile- and silo-based Yars missiles. SS-27 Mod 2 upgrades now appear to be complete at the 39th Guards Missile Division at Novosibirsk, the 42nd Missile Division at Nizhny Tagil, the 14th Missile Division at Yoshkar-Ola, and the 29th Guards Missile Division at Irkutsk. Although these divisions now all have been equipped with the SS-27 Mod 2, some of the garrisons are not equipped to accommodate all the vehicles required to support the launchers and will continue to undergo construction for several years. After several years of temporarily basing the 382nd Guards Missile Regiment at a temporary open-air location, commercial satellite imagery now indicates that the possible permanent garrison is nearing completion (Figure 2).

The 35th Missile Division at Barnaul appears to be nearing completion of its rearmament to the SS-27 Mod 2. The first regiment at Barnaul (the 479th Guards Missile Regiment) went on preliminary combat alert duty with the Yars in September 2019 and full combat duty in December 2019 (Russian Federation Defense Ministry 2019c). The Barnaul division formally accepted its second Yars regiment (the 480th Missile Regiment) in December 2020 (RIA Novosti 2020a). In March 2021, Col. Gen. Karakaev announced that the entire Barnaul division would be re-armed with Yars ICBMs by the end of the year, and given that Karakaev did not include further plans for the Barnaul division in his 2022 rearmament schedule, it is possible that rearmament at this division is now largely complete (Russian Federation Defense Ministry 2021b).

The next mobile ICBM division to be upgraded is the 7th Missile Division at Vypolsovo. The Vypolsovo division, which is the smallest ICBM division with only 18 launchers, started early preparations for the upgrade in 2019 (Tikhonov 2019), and it is possible that one of its two regiments has already stood down its SS-25 launchers. In January 2022, the Russian Ministry of Defense announced that the Vypolsovo division would be rearmed with SS-27 Mod 2 missiles in 2022 (Interfax 2022).

The 28th Guards Missile Division at Kozelsk is the only silo division with SS-27 Mod 2 and continues to expand: the first regiment (the 74th Missile Regiment) officially began combat duty with its full complement of 10 missiles in November 2018, after initially being declared operational (likely with just six missiles) in 2015 (Russian Federation Defense Ministry 2018b). Satellite pictures show that upgrades of the second regiment (the 168th Missile Regiment) are complete, as was confirmed by Col. Gen. Karakaev at the end of 2020. (TASS 2020l). In December 2021, Col. Gen. Karakaev stated that the third missile regiment at Kozelsk (the 214th Missile Regiment) had been placed on combat alert; however, satellite imagery suggests that the necessary infrastructure upgrades have only taken place at a couple of silos and are still ongoing. His statement might indicate that a portion of the regiment has reached some prelimary readiness status. Given the time it took to complete the upgrades of the first two regiments at Kozelsk, it remains to be seen whether the Yars upgrade can be fully completed by 2024 as scheduled.

Apart from the missiles and silos themselves, the ICBM upgrade involves extensive modification of external fences, internal roads, and support facilities. Each site is also receiving a new “Dym-2” perimeter defense system including automated grenade launchers, small arms fire, and remote-controlled machine gun installations (Krasnaya Zvezda 2021a; Russia Insight 2018).

Final development and deployment of a compact SS-27 version, known as Rubezh (Yars-M or RS-26), appears to have been delayed at least until the next armament program in the late 2020s (TASS 2018a). A rail-based version known as Barguzin appears to have been canceled.

Russia is also developing the heavy SS-X-29, or Sarmat (RS-28), which will begin replacing the SS-18 (RS-20V) at Uzhur in 2022. Three ejection tests were conducted in December 2017, March 2018, and May 2018 at the Plesetsk Space Center, involving the cold launch and test firing of the Sarmat’s first stage and booster engine. The closing test stages, which will include a test launch with the 62nd Missile Division at Uzhur, were supposed to be completed by the end of 2020; however, this has been continuously delayed, partly due to a manufacturing delay for the missile’s command module (War Bolts 2022). The first Sarmat flight test is now scheduled for the first quarter of 2022 at the new Severo-Yeniseysky proving ground (TASS 2021a) and will be followed by several more tests. If these tests are successful, Sarmat will officially be handed over to the military and serial production will begin. As of March 2020, Sarmat’s industrial production line reportedly had completed all the necessary upgrades to prepare for serial production (TASS 2020a).

There are many rumors about the SS-X-29, which some in the media have dubbed the “Son of Satan” because it is a follow-on to the SS-18, which the United States and NATO designated “Satan”—presumably to reflect its extraordinary destructive capability. Rumors that the SS-X-29 could carry 15 or more MIRV warheads, though, seem exaggerated. We expect that it will carry about the same number as the SS-18 plus penetration aids. It is likely that a small number will be equipped to carry the Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle, which are currently being installed on a limited number of SS-19 Mod 4 boosters at Dombarovsky. If the SS-X-29 replaces all current SS-18s, it will be installed in a total of 46 silos of the three regiments at the Dombarovsky missile field and four regiments at the Uzhur missile field (six regiments of six missiles and one regiment of 10 missiles). In December 2020, Col. Gen. Sergei Karakaev announced that the first Sarmat missiles would be “put on alert” at Uzhur sometime in 2022 (Krasnaya Zvezda 2020a). It appears that the first regiment to receive Sarmat might be the 302nd Missile Regiment; upgrades to the regiment’s silos are clearly visible on commercial satellite imagery, indicating that the regiment’s SS-18s have already been removed (see Figure 1).

The new Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle is designed to evade missile defenses and is initially being fitted atop modified SS-19 missiles (SS-19 Mod 4) at Dombarovsky and possibly later on SS-X-29 missiles at Uzhur. Russia is currently deploying the new weapon at a rate of two per year: the first two missiles at Dombarovsky began combat duty on December 27th, 2019, followed by another two in December 2020 (TASS 2019f; Russian Federation Defense Ministry 2020a). The regiment received its final two missiles—achieving a full complement of six missiles––in December 2021 (Russian Federation 2021a). The first two missiles in the second Avangard regiment will reportedly be placed on combat duty in 2022 or 2023, with the entire regiment completing its rearmament by the end of 2027 to coincide with the completion of the current state armament program (Krasnaya Zvezda 2021a; TASS 2021c). Similar to the new silos at Kozelsk, the modified Dombarovsky silos appear to have some form of perimeter defense system.

In December 2021, Karakaev stated that “a new mobile ground-based missile system” is being developed (Krasnaya Zvezda 2021a). It is possible that this refers to the Osina-RV ICBM, a follow-on system reportedly derived from the Yars ICBM (War Bolts 2021). Flight tests of the siloed system are expected within the next couple of years. Russia has also recently commenced work on its strategic “Kedr” project; however, it remains unclear whether Kedr refers to a specific type of next-generation ICBM, or whether it is the name of the overall campaign to develop a new suite of next-generation strategic missile systems (TASS 2021p).

While the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review anticipated that Russian missile forces will increase over time, the evidence for this still is not clear. The US National Air and Space Intelligence Center predicted in 2020 that “the number of missiles in the Russian ICBM force will continue to decrease because of arms control agreements, aging missiles, and resource constraints” (US Air Force 2020, 26). With the ongoing modernization, the force level will likely level out as the modernization program is completed, although the modernized force will be able to deliver more warheads if all the single-warhead Topol-M (SS-27 Mod 1) ICBMs are replaced with MIRVed Yars (SS-27 Mod 2).

According to Col. Gen. Karakaev, Russia has conducted more than 25 ICBM test launches over the past five years, and plans to conduct at least ten ICBM launches in 2022, indicating a significant increase in test frequency (Krasnaya Zvezda 2021a). The Strategic Rocket Force often test-launches its missiles to the Sary-Shagan test site in Kazakhstan. However, given that Kazakhstan is a state party to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons––which entered into force in January 2021––it is unclear whether the country will continue to allow Russia to use its test site at Sary-Shagan for its ICBM launches. Article 4(2) of the treaty notes that each state party must ensure “the elimination or irreversible conversion of all nuclear-weapons-related facilities” (United Nations 2017). This would necessarily include Sary-Shagan, which would be considered nuclear weapons-related infrastructure if it is still being used for ICBM testing. This means that Kazakhstan faces a tough decision over whether to fully comply with the treaty and risk souring relations with Russia, or whether to dilute its compliance. This potential compliance issue could be the reason why Russia is building a new proving ground for its Sarmat tests at Severo-Yeniseysky, a decision which was announced in December 2020 (Russian Federation 2020a).

Russia is also developing a nuclear-powered, ground-launched, nuclear-armed cruise missile, known as 9M730 Burevestnik (NATO’s designation is SSC-X-9 Skyfall). This missile has faced serious setbacks: According to US military intelligence, it has failed nearly a dozen times since its testing period began in June 2016 (Panda 2019a). In November 2017, a failed test resulted in the missile being lost at sea, which required a substantial recovery effort (Macias 2018). A similar recovery effort in August 2019 resulted in an explosion that killed five scientists and two soldiers at Nenoksa; the explosion’s connection to Skyfall was confirmed by US State Department officials in October 2019 (DiNanno 2019). Due to these setbacks, it is possible that the Burevestnik program has been put on pause; there were no declared tests of the system in 2020 or 2021 and, unlike other elements of Russia’s nuclear forces, it was not mentioned in Defense Minister Shoigu’s year-end remarks in either year. In August 2021, satellite imagery appeared to indicate that Russia was preparing for another test of the Burevestnik system at Novaya Zemlya; however, it is unclear whether such a test actually took place (Lewis 2021; Cohen 2021).

Submarines and submarine-launched ballistic missiles

The Russian Navy operates 10 nuclear-powered nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) of two classes: five Delta IV (Project 667BRDM) and five Borei (Project 955), two of which are improved Borei-A (Project 955A) submarines.3 Each submarine can carry 16 SLBMs, and each SLBM can carry several MIRVs, for a combined maximum loading of approximately 800 warheads. However, not all of these submarines are fully operational, and the warhead loading on some of the missiles may have been reduced as part of New START implementation; the total number of warheads carried is possibly around 608.

For the next couple of years, the backbone of Russia’s nuclear submarine force will continue to be the five third-generation Delta IVs built between 1985 and 1992, each equipped with 16 SLBMs. All Delta IVs are part of the Northern Fleet and based at Yagelnaya Bay (Gadzhiyevo) on the Kola Peninsula. Russia has upgraded the Delta IVs to carry modified SS-N-23 SLBMs, known as Layner (or Liner), each of which might carry four warheads (Podvig 2011). Normally three or four of the five Delta IVs are operational at any given time, with the other one or two in various stages of maintenance. In March 2021, three SSBNs—possibly two Delta IV SSBNs and one Borei SSBN—simultaneously surfaced alongside each other near the North Pole during Russia’s “Umka-2021” major Arctic exercise (Russian Federation Defense Ministry 2021a). Russia previously possessed six Delta IV SSBNs, but in April 2021, defense sources suggested that one of Russia’s Delta IV SSBNs––Yekaterinburg (K-84)––would be withdrawn from the Northern Fleet and decommissioned in 2022 after 36 years of service (TASS 2021f).

All remaining Delta III SSBNs have been withdrawn from strategic service. Two (K-223 Podolsk and K-433 Svyatoy Georgiy Pobedonosets) were decommissioned in 2018 (Podvig 2018), and the commander of the Russian Pacific Fleet submarine force, Vice-Admiral Vladimir Dmitriev said in late-2021 that the Delta III SSBN—Ryazan (K-44)—had been converted from a missile submarine cruiser to an attack (general-purpose) submarine (Krasnaya Zvezda 2021b).

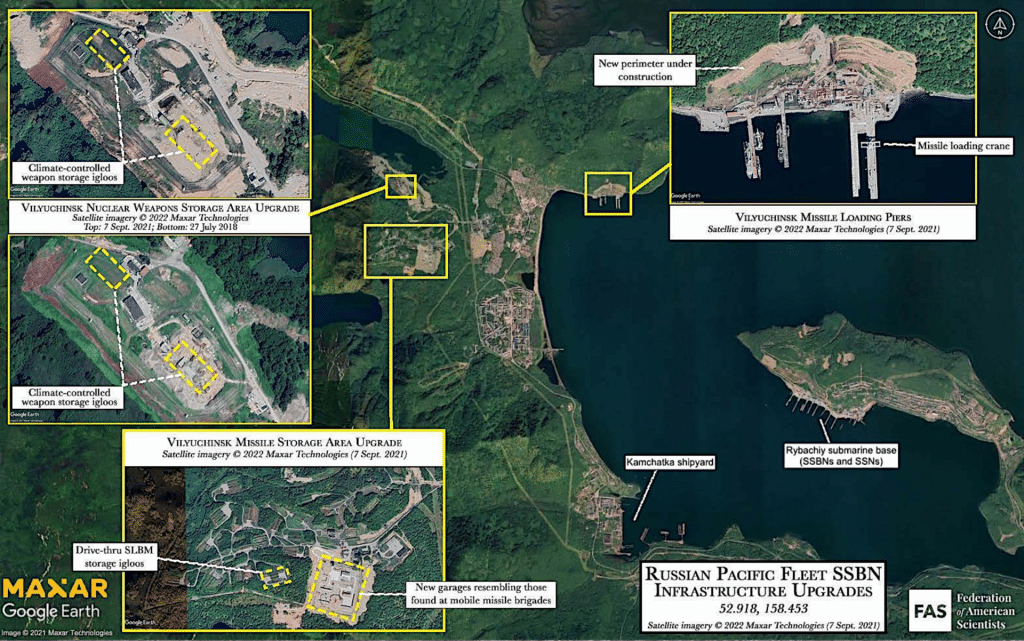

Each Borei (Project 955/A) SSBN is armed with 16 SS-N-32 (Bulava) SLBMs that can carry up to six warheads each. It is possible that the missile payload has been lowered to four warheads each to meet the New START limit on deployed strategic warheads. In May 2018, one of the new boats, Yuri Dolgoruki (K-535), salvo-fired four Bulavas as part of a test launch (Russian Federation Defense Ministry 2018a). In December 2020, another Borei, Vladimir Monomakh (K-551), salvo-fired four Bulavas during a test launch from the Sea of Okhotsk—the 35th-38th tests of the Bulava SLBM, and the first Bulava launch from a Pacific Fleet submarine (Russian Federation Defense Ministry 2020b; Podvig 2020). Five Boreis are currently in service, with another five in various stages of construction, for a total of 10 planned Borei SSBNs. The first boat, Yuri Dolgoruki, is based at Yagelnaya in the Northern Fleet. The second boat, Alexander Nevsky (K-550), arrived at its home base at Rybachiy near Petropavlovsk in September 2015, where it was joined by the third Borei, Vladimir Monomakh (K-551), in September 2016.

The first of the improved Borei-A/II (Project 955A) SSBNs, and the fourth Borei submarine in total, Knyaz Vladimir (K-549), was after much delay finally accepted into the Navy on June 12, 2020 (Russian Federation Defense Ministry 2020c).

The fifth Borei—Knyaz Oleg (K-552)—underwent hull pressure tests in November 2016 and was originally scheduled for delivery in 2018 but was delayed for several years before finally being launched in July 2020 (TASS 2020g). The boat began its sea trials in June 2021 and launched a MIRVed Bulava SLBM––the 39th Bulava test-launch––in October 2021 (TASS 2021d; Lindemann 2021). Knyaz Oleg was delivered to the Navy in December 2021 and will join the Pacific Fleet (Sevmash 2021a), bringing the total number of Borei SSBNs in the Pacific Fleet to three. Significant upgrades are underway at the Pacific SSBN base (see Figure 3).

The keel of the sixth boat—Generalissimus Suvorov—was laid down in December 2014 for possible completion in 2018 but has also been delayed. In December 2020, Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu declared that the Navy was expected to receive the Generalissimus Suvorov in 2021 (Russian Federation 2020a). However, the boat was only launched in December 2021, meaning that it is not expected to be delivered to the Navy before December 2022 (Sevmash 2021b; Russian Federation 2021a).

The keel for the seventh boat—Emperor Alexander III—was laid down in December 2015 for scheduled delivery in 2019 but has also been delayed. It is now expected that the boat will be launched in December 2022, begin sea trials in the second half of 2023, and be delivered to the Navy’s Pacific Fleet in December 2023 (TASS 2021e).

The keel for the eighth Borei SSBN—Knyaz Pozharsky—was laid in December 2016 for potential delivery between 2021 and 2023 (Russian Federation Defense Ministry 2016).

The keels for the ninth and tenth Borei SSBNs—Dmitry Donskoy and Knyaz Potemkin—were laid in August 2021 (Sevmash 2021c). Given that the Dmitry Donskoy shares its name with Russia’s only remaining operational Typhoon-class SSBN—which now only operates as a weapons testing platform—it seems likely that the older Typhoon SSBN will be removed from service before the delivery of the newer Borei SSBN. These two SSBNs are scheduled to be delivered by the completion of the State Armaments Program in 2027, bringing the total fleet up to 10 boats (Russian Federation 2021b). Eventually, five SSBNs will be assigned to the Northern Fleet, and five will be assigned to the Pacific (TASS 2018b).

In December 2020, Russia conducted its annual nuclear force readiness exercise, during which a Delta-IV SSBN launched a Sineva or Layner SLBM from the Barents Sea (Russian Federation Defense Ministry 2020f). In 2019, technical malfunctions during the strategic exercises prompted aborted launches––in the case of planned SLBM launches––or required the use of backup launch systems, in the case of 3M-54 Kalibr cruise missile launches (Sidorkova and Kanaev 2019).

The Russian Navy is also developing the Status-6 Poseidon mentioned above—a nuclear-powered, very long range, nuclear-armed torpedo. Underwater trials began in December 2018. The weapon is scheduled for delivery in 2027 and will be carried by specially configured submarines (TASS 2018f). The first of these special submarines—the Project 09852 Belgorod (K-329)—was launched in April 2019 and was originally scheduled for delivery to the Navy by the end of 2020; however, it only began sea trials in June 2021 and returned to dry dock in October 2021 (Sutton 2021a; Sutton 2021b). State trials are scheduled for 2022, which could indicate that delivery to the Navy could be delayed until late 2022 (TASS 2021o). Belgorod will become Russia’s largest submarine and reportedly will be capable of carrying up to six Poseidon torpedoes (TASS 2019d). The launch of the second Poseidon-capable submarine—Project 09851 Khabarovsk—was expected to take place in the autumn of 2021, but appears to have been delayed until 2022 (TASS 2021g). Khabarovsk will reportedly also be capable of carrying up to six Poseidon torpedoes (TASS 2020b).

Strategic bombers

Russia operates two types of nuclear-capable heavy bombers: the Tu-160 Blackjack and the Tu-95MS Bear-H. We estimate that there are 60 to 70 bombers in the inventory, of which perhaps only 50 are counted as deployed under New START. Both bomber types can carry the nuclear AS-15 Kent (Kh-55) air-launched cruise missile and upgraded versions are being equipped to carry the new AS-23B (Kh-102) nuclear cruise missile. Two versions of the Tu-95 are thought to exist: Tu-95H6, which can carry up to six missiles internally, and Tu-95H16, which was built to carry missiles both internally and on wing-mounted pylons for a total of 16 missiles. The Tu-95 modernization program is equipping the Tu-95s to carry eight AS-23B missiles externally for a maximum of 14 missiles per aircraft. The Tu-160s are also being modernized to carry up to 12 AS-23B internally. The new AS-23B being added during bomber modernization will likely replace the AS-15.

It is unclear how many nuclear weapons are assigned to the heavy bombers. Each Tu-160 can carry up to 40,000 kilograms (about 44 tons) of ordnance, including 12 nuclear AS-15B air-launched cruise missiles. The Tu-95MS can carry six to 16 cruise missiles, depending on configuration. Combined, the bombers could potentially carry over 800 weapons, but we estimate weapons only exist for deployed bombers for a total of approximately 580 bomber weapons. The Tu-160 may also have a secondary mission with nuclear gravity bombs, but it seems unlikely that the old and slow Tu-95 would stand much of a chance against modern air defense systems.4 According to Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, Russian strategic bombers performed 50 flights on preset routes in 2020 (Russian Federation 2020a). Most of the nuclear weapons assigned to the bombers are thought to be in central storage, with only a couple hundred deployed at the two bomber bases. Modernization of the nuclear weapons storage bunker at Engels Air Base continues.5

The aging Tu-160s and most of the Tu-95MSs have also been undergoing various minor upgrades for several years. The first seven upgraded Tu-160s and Tu-95MSs returned to service in 2014, another nine followed in 2016, and five more were added in 2018. Only a few dozen of the Tu-95MSs—perhaps around 44—will be modernized, while at least 10 Tu-160s were slated to be modernized by 2019, although there has been some delay. Two additional Tu-160s and five Tu-95MS bombers were reportedly upgraded in 2020, followed by four additional Tu-95MS bombers in 2021 (Russian Federation 2020a; Russian Federation 2021a).

In addition to these minor upgrades, Russia is conducting a significant modernization campaign for its aging Tu-160 force; however, there is some confusion with regards to the nomenclature of the upgraded planes, with various news outlets using Tu-160, Tu-160M, Tu-160M1, and Tu-160M2 designations interchangeably. It appears that there are two distinct modernization programs for the Tu-160 taking place simultaneously: one program involving a “deep modernization” of existing Tu-160 airframes to incorporate next-generation engines, as well as new avionics, navigation, and radar systems, and another program involving the incorporation of similar next-generation systems onto completely new airframes (Krasnaya Zvezda 2020b; Butowski 2016; TASS 2018g).

The first public flight of the Tu-160M (sometimes referred to as Tu-160M1) prototype with its older engine was conducted in January 2018 at the Gorbunov Aviation Factory in Kazan, during a visit by President Putin. Immediately after the visit, a 160 billion ruble contract (approximately $2.13 billion) was signed for the modernization of 10 “deeply modernized” Tu-160M aircraft using existing airframes by 2027 (Russian Federation 2018b).

The Tu-160M “deep modernization” campaign appears to be separate from the Tu-160M2 project, which requires serial production of completely new airframes in order to accommodate the 50-aircraft order made by the Russian Aerospace Force. During Putin’s 2018 factory visit in Kazan, he described the requirement for the new aircraft: “The older version of this plane was discontinued in 1993. In 2015, we decided to modernize it and resume production. This, in fact, is a completely different aircraft, including avionics and everything else. […] It may look the same, but the engine, the flight range and the capacity are different” (Russian Federation 2018b).

Both the Tu-160M and Tu-160M2 aircraft will reportedly include a new engine—the NK-32-02—that is said to increase the aircraft’s range by approximately 1,000 kilometers, or about 621 miles (TASS 2017). The Tu-160M’s first flight with its older engine was conducted in February 2020, and the aircraft’s first flight with its next-generation engine took place in November 2020, although the United Aircraft Corporation declined to show pictures of the November test flight due to classification concerns, instead electing to couple its announcement with pictures of an older version of the plane (United Aircraft Corporation 2020). A second Tu-160M, converted from an older Tu-160 airframe, began ground tests at the Gorbunov factory in December 2020 (TASS 2020e). In January 2019, Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu announced that the first Tu-160M aircraft would be delivered to the Russian Aerospace Force in 2021; however, this has been postponed by at least a year (Russian Federation Defense Ministry 2019b; Russian Federation 2020a). In December 2021, Defense Ministry Shoigu announced plans to deliver two Tu-160M bombers to the Russian Air Force in 2022 (Russian Federation 2021a).

The first newly-manufactured Tu-160M2 bomber conducted its maiden flight in January 2022 (United Aircraft Corporation 2022). The Tu-160M2 is expected to include a communications suite drawn from the fifth-generation Su-57 fighter (TASS 2020c, 2020g). It is possible that the eventual target of 50 new Tu-160M2 bombers might be exaggerated, but if it is accurate, it would probably result in the retirement of most, if not all, of the remaining Tu-95MSs, which are expected to be retired no later than 2035.

The Tu-160 modernization program, meanwhile, is only a temporary bridge to the next-generation bomber known as PAK-DA, the development of which has been underway for several years. The Russian government signed a contract with manufacturer Tupolev in 2013 to construct the PAK-DA at the Kazan factory. Research and development work on the PAK-DA has reportedly been completed, and the aircraft is expected to share many systems with the Tu-160M2 (TASS 2019h). Construction of the first aircraft’s cockpit reportedly began in the spring of 2020, and final assembly has been postponed from 2021 to 2023 in advance of flight trials (TASS 2020f; TASS 2021h). Preliminary tests of the PAK-DA are scheduled for April 2023 (to be completed by fall 2025), and state tests are scheduled for February 2026. Initial production is expected to begin in 2027, with serial production beginning in 2028 or 2029 (Izvestia 2020; TASS 2019a). However, it is unclear whether the Russian aviation industry has enough capacity to develop and produce two strategic bombers at the same time, and as such this development schedule could face delays.

Nonstrategic nuclear weapons

Russia is updating many of its shorter-range, so-called “nonstrategic” nuclear weapons and introducing new types. This effort is less clear and comprehensive than the strategic forces modernization plan but also involves phasing out Soviet-era weapons and replacing them with newer but fewer weapons. New systems are being added, which prompted the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review to accuse Russia of “increasing the total number of [nonstrategic nuclear] weapons in its arsenal, while significantly improving its delivery capabilities” (US Defense Department 2018, 9). In the longer term, though, the emergence of more advanced conventional weapons could potentially result in reduction or retirement of some existing nonstrategic nuclear weapons.

Regardless of the number, the Russian military continues to attribute importance to nonstrategic nuclear weapons for use by naval, tactical air, and air- and missile-defense forces, as well as on short-range ballistic missiles. Part of the rationale is that nonstrategic nuclear weapons are needed to offset the superior conventional forces of NATO and particularly the United States. Russia also appears to be motivated by a desire to counter China’s large and increasingly capable conventional forces in the Far East, and by the fact that having a sizable inventory of nonstrategic nuclear weapons helps Moscow keep overall nuclear parity with the combined nuclear forces of the United States, the United Kingdom, and France.

After the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review was published, defense sources distributed inaccurate and exaggerated information in Washington that attributed nuclear capability to several Russian systems that had either been retired or were not, in fact, nuclear. Moreover, although the Nuclear Posture Review claims that Russia has increased its nonstrategic nuclear weapons over the past decade, the inventory has in fact declined significantly—by about one-third—during that period (Kristensen 2019). Moreover, although the Trump Nuclear Posture Review stated that Russia has “up to 2,000” nonstrategic nuclear weapons and defense officials frequently have claimed it has more than 2,000, the US Defense Intelligence Agency’s Worldwide Threat Assessment in 2021 stated that “Russia probably possesses 1,000 to 2,000 nonstrategic nuclear warheads” (US Defense Intelligence Agency 2021, 54). The range reflects difference estimates within the US intelligence community; the military uses the higher number. Rumors emerged in early-2022 that some in the Intelligence Community believe the number of Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons could increase significantly—potentially doubling—by 2030 (Bender 2022, Kristensen 2022).6

We estimate that Russia today has approximately 1,912 nonstrategic nuclear warheads, potentially fewer, assigned for delivery by air, naval, ground, and various defensive forces. Although there are many rumors about additional nuclear systems, there is little authoritative public information available. This estimate, and the categories of Russian weapons that we have been describing in the Nuclear Notebook for years, was echoed by the Nuclear Posture Review, which stated:

“Russia is modernizing an active stockpile of up to 2,000 nonstrategic nuclear weapons, including those employable by ships, planes, and ground forces. These include air-to-surface missiles, short range ballistic missiles, gravity bombs, and depth charges for medium-range bombers, tactical bombers, and naval aviation, as well as anti-ship, anti-submarine, and anti-aircraft missiles and torpedoes for surface ships and submarines, a nuclear ground-launched cruise missile in violation of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, and Moscow’s antiballistic missile system (US Defense Department 2018, 53).”

The Nuclear Posture Review also said:

“Russia possesses significant advantages in its nuclear weapons production capacity and in nonstrategic nuclear forces over the US and allies. It is also building a large, diverse, and modern set of nonstrategic systems that are dual-capable (may be armed with nuclear or conventional weapons). These theater- and tactical-range systems are not accountable under the New START Treaty and Russia’s nonstrategic nuclear weapons modernization is increasing the total number of such weapons in its arsenal, while significantly improving its delivery capabilities. This includes the production, possession, and flight testing of a ground-launched cruise missile in violation of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. Moscow believes these systems may provide useful options for escalation advantage. Finally, despite Moscow’s frequent criticism of US missile defense, Russia is also modernizing its long-standing nuclear-armed ballistic missile defense system and designing a new ballistic missile defense interceptor (US Defense Department 2018, 9).”

These paragraphs constituted the first substantial official US public statement on the status and composition of the Russian nonstrategic nuclear arsenal in more than two decades, even though the paragraphs also raise questions about assumptions and counting rules. Most of the nonstrategic weapon systems are dual-capable, which means not all platforms may be assigned nuclear missions, and not all operations are nuclear. Moreover, many of the delivery platforms are in various stages of overhaul and would not be able to launch nuclear weapons at this time.

Sea-based nonstrategic nuclear weapons

As far as we can ascertain, the biggest user of nonstrategic nuclear weapons in the Russian military is the navy, which we estimate has roughly 935 warheads for use by land-attack cruise missiles, anti-ship cruise missiles, anti-submarine rockets, anti-aircraft missiles, torpedoes, and depth charges. These weapons may be used by submarines, aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, frigates, corvettes, and naval aircraft. This number may be lower because not all vessels with dual-capable weapon systems may actually be assigned nuclear warheads.

Major naval modernization programs focus on the next class of nuclear attack submarines, known in Russia as Project 885/M or Yasen/-M. The program is progressing very slowly. The first of these boats, known as Severodvinsk, finally entered service in 2015 after 16 years of construction and is thought to be equipped with a nuclear version of the Kalibr land-attack sea-launched cruise missile (the SS-N-30A) (Gertz 2015). It can also launch the SS-N-26 (3M-55) anti-ship/land-attack cruise missile, which the US National Air and Space Intelligence Center says is “nuclear possible” (US Air Force 2020, 36). The second boat, and the lead ship of the improved Yasen-M class—known as Kazan—was originally scheduled to join the Northern Fleet in late 2019 (TASS 2018c); however, the boat was delayed due to the poor results of its dockside trials, which indicated that “some of the ship’s auxiliary sub-assemblies and mechanisms do not meet the requirements of the specifications set by the Defense Ministry” (TASS 2019b). The Kazan underwent sea trials in late 2020, successfully hitting a target over 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) away with a Kalibr cruise missile (TASS 2020h). The Kazan was delivered to the Navy in May 2021 and is now operational with the Northern Fleet (TASS 2021k). The next Yasen-M boat––the Novosibirsk––began sea trials in July 2021, was delivered to the Navy’s Pacific Fleet in December 2021, and may become operational in 2022 (Manaranche 2021; Sevmash 2021a).

Six additional Yasen-M SSGNs––named Krasnoyarsk, Arkhangelsk, Perm, Ulyanovsk, Voronezh, and Vladivostok––are under various stages of construction. The Krasnoyarsk was launched in July 2021 and will likely conduct its sea trials in late 2022 (TASS 2021l). The five other boats were laid down in 2015, 2016, 2017, 2020, and 2020, respectively (RIA Novosti 2015; TASS 2016b; TASS 2020m).

The first Yasen submarine is reportedly 10 to 12 meters (about 33 to 39 feet) longer than the improved Yasen-M submarine and can therefore accommodate 40 Kalibr missiles, eight more than its successors (Gady 2018). The Yasen-M boats reportedly also have improved reactors and sonar systems, which may enhance their ability to evade detection (Kaushal et al. 2021).

In addition to dual-capable Kalibr land-attack cruise missiles, the Yasen-class submarines will also be able to deliver the SS-N-26 anti-ship cruise missile, SS-N-16 (Veter) nuclear anti-submarine rockets, as well as nuclear torpedoes. Additionally, in October 2021 the Severodvinsk successfully test-launched the Tsirkon hypersonic missile from surface and sub-surface positions––the first tests of the new system from a submarine (TASS 2021i). According to Russian military officials, the Yasen-M submarines are able to salvo-launch several different types of missiles through the use of “universal launchers” that can accommodate multiple systems (Interfax 2021; TASS 2021j).

Other upgrades of naval nonstrategic nuclear-capable platforms include those planned for the Sierra class (Project 945), the Oscar II class (Project 949A), and the Akula class (Project 971). While the conventional version of the Kalibr is being fielded on a wide range of submarines and ships, the nuclear version will likely replace the current SS-N-21 nuclear land-attack cruise missile on select attack submarines. There is also speculation that Russia might consider building a new type of cruise missile submarine based on the Borei SSBN design, which would be called Borei-K. The Borei-Ks could potentially carry nuclear-armed cruise missiles instead of ballistic missiles, and if they were approved then they would be scheduled for delivery after 2027 (TASS 2019c). However, given that the incoming Yasen-M submarines are also capable of delivering nuclear-armed cruise missiles, there may be no need for a new type of SSGN.

Air-based nonstrategic nuclear weapons

The Russian Air Force is the military’s second-largest user of nonstrategic nuclear weapons, with roughly 500 such weapons assigned for delivery by Tu-22M3 (Backfire) intermediate-range bombers, Su-24M (Fencer-D) fighter-bombers, the new Su-34 (Fullback) fighter bomber, and the MiG-31K. All types can deliver nuclear weapons. A total of four regiments are now equipped with the new Su-34, which is replacing the Su-24, with more than 125 aircraft delivered so far. Russia is also purchasing an additional 76 upgraded units of the Su-34M with improved avionics, resulting in a total future fleet of approximately 200 Su-34s (Lavrov and Krezul 2020).

The Tu-22M3 can also deliver Kh-22 (AS-4 Kitchen) air-launched cruise missiles, which is being replaced by an upgraded missile known as Kh-32. The Tu-22M3 and Su-24M are also being upgraded, and the new Tu-22M3M—which reportedly contains 80 percent entirely new avionics and shares a communications suite with the new Su-57 fighter—conducted its maiden flight in December 2018 (United Aircraft Corporation 2018; TASS 2020d). The second prototype of the upgraded Tu-22M3M conducted its first flight in March 2020, and has since conducted four additional flight tests—one of which tested the plane’s resilience at supersonic speeds (TASS 2020i). The Tu-22M3M––in addition to the Tu-160M and future PAK-DA strategic bombers––will eventually be equipped with a new Kh-95 hypersonic missile, a prototype of which has reportedly already been tested (RIA Novosti 2021c).

It is possible that the Russian Air Force also has various types of other guided bombs, air-to-surface missiles, and air-to-air missiles with nuclear capability. If they exist, however, these systems would probably already be included in the Defense Intelligence Agency’s estimate of 1,000-2,000 nonstrategic warheads.

Russia has also developed a new long-range, dual-capable, air-launched ballistic missile system known as the 9-A-7760 Kinzhal. The missile, which appears similar to the ground-launched SS-26 short-range ballistic missile used on the Iskander system, allegedly has a range of up to 2,000 kilometers (about 1,243 miles) if launched from a specially modified MiG-31K (Foxhound) designated as MiG-31IK, and up to 3,000 kilometers (about 1,864 miles) if launched from the Tu-22M3 bomber (the range is the combined combat range of the aircraft plus the missile). The MiG-31IK cannot carry both the Kinzhal and its regular air-to-air missiles and must therefore be deployed alongside a protective air detail (TASS 2018h). The Kinzhal could potentially be used against targets on both land and sea and has reportedly been deployed on experimental combat duty in the Southern Military District since December 2017 (TASS 2018d). The Kinzhal was publicly demonstrated for the first time in an airshow in August 2019, although it is unclear if the missile was actually fired during the competition (TASS 2019e). In December 2021, Defense Minister Shoigu announced that in 2021 “a separate aviation regiment was formed, armed with MiG-31IK aircraft with the Dagger hypersonic missile” (Russian Federation 2021a), apparently in the North Fleet area on the Kola Peninsula. Plans reportedly are underway to equip the Western and Central Military Districts with Kinzhal missiles by 2024 (Izvestia 2021, TASS 2021m).

Additionally, the Russian Aerospace Force reportedly received its first batch of Su-57 (PAK-FA) fighter jets in late 2020 (TASS 2020j). Four more were scheduled for delivery in 2021––although given program delays and setbacks it is unclear whether any of these delivered took place––and the delivery of 22 aircraft are scheduled by the end of 2024 (Suciu 2021). The full contract is expected to comprise 76 planes for delivery by the end of 2028 (TASS 2020k). The US Defense Department says that the Su-57s are nuclear-capable (US Defense Department 2018). They will reportedly also be equipped with hypersonic “missiles with characteristics similar to that of the Kinzhal” (TASS 2018e).

Nonstrategic nuclear weapons in missile defense

The 2018 Nuclear Posture Review also asserted that Russia continues to use nuclear warheads in its air and missile defense forces; however, the document did not identify which systems have dual-capability or how many are assigned nuclear warheads. The US Defense Intelligence Agency said in its March 2018 Worldwide Threat Assessment that: “Russia may also have warheads for surface-to-air and other aerospace defense missile systems” (Ashley 2018). Russia currently operates several different kinds of missile defense complexes for use against different tiers of threats. The mobile S-300 and S-400 systems are designed for theater air and missile defense, and US government sources privately indicate that both the S-300 (SA-20) and S-400 (SA-21) are dual-capable.

Russia is developing several next-generation air and missile defense systems to supplement––and in some cases––replace its older systems. It appears that several of these systems, including the S-550, Nudol, and Aerostat, are expected to utilize conventional warheads rather than nuclear ones; however, their improved ranges and speeds will also likely offer them the capabilities to target satellites in orbit (Hendrickx 2021; TASS 2021n).

The A-135 antiballistic missile defense system around Moscow is equipped with 68 nuclear-tipped 53T6 Gazelle interceptors. An upgrade of the A-135 is underway, and it will be known as A-235 (Krasnaya Zvezda 2017); however, it remains unclear whether the A-235 system will use either nuclear or conventional warheads, or perhaps instead rely on kinetic hit-to-kill technology.

Russian officials said over a decade ago that about 40 percent of the country’s 1991 stockpile of air defense nuclear warheads remained. Alexei Arbatov, then a member of the Russian Federation State Duma defense committee, wrote in 1999 that the 1991 inventory included 3,000 air defense warheads (Arbatov 1999). Many of those were probably from systems that had been retired, and US intelligence officials estimated that the number had declined to around 2,500 by the late 1980s (Cochran et al. 1989), in which case the 1991 inventory might have been closer to 2,000 air defense warheads. In 1992, Russia promised to destroy half of its nuclear air defense warheads, but Russian officials said in 2007 that 60 percent had been destroyed (Pravda 2007).

If those officials were correct, the number of nuclear warheads for Russian air defense forces might have been 800 to 1,000 a decade ago. Assuming that the inventory has shrunk further since 2007 (due to the improving capabilities of conventional air-defense interceptors and continued retirement of excess warheads), we estimate that nearly 290 nuclear warheads remain for air defense forces today, plus an additional roughly 90 for the Moscow A-135 missile defense system and coastal defense units, for a total inventory of about 380 warheads. However, it must be emphasized that this estimate comes with considerable uncertainty.

Ground-based nonstrategic nuclear weapons

Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu announced in December 2019 that the upgrade of all army missile brigades to the 350-kilometer (217 mile) range SS-26 (Iskander) short-range ballistic missile had been completed (Russian Federation 2019), but construction continues at several bases two years later and not all have missile depots. This includes at least 12 brigades: four in the Western Military District; two in the Southern Military District; two in the Central Military District, and at least four in the Eastern Military District. Each brigade has 12 launchers, each with two missiles for a total of 24 missiles (at least one reload is in storage). In 2019, Izvestia quoted unnamed defense ministry sources saying that each brigade would receive an additional battalion so that each brigade in the future would have 16 launchers with 32 missiles (Izvestia 2019). We estimate that there are roughly 70 warheads for short-range ballistic missiles. There are also unconfirmed rumors that the SSC-7 (9M728 or R-500) ground-launched cruise missile may have nuclear capability.

The US government also says that Russia has developed and deployed a dual-capable ground-launched cruise missile in violation of the now-defunct Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. The missile is identified as the 9M729 (SSC-8) (US State Department 2019a). In 2018, former Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats said Russia initially tested the 9M729 to prohibited ranges from a fixed launcher, then tested it to permitted ranges from a mobile launcher (Office of the Director National Intelligence 2018). US Gen. Paul Selva, former vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, however, told Congress in 2017 that the 9M729 deployment at that time did not give Russia a military advantage: “Given the location of the specific missiles and deployment, they don’t gain any advantage in Europe” (Brissett 2017). After having denied the existence of a 9M729 missile, the Russian military in January 2019 displayed what it said was a launcher, missile canisters, and schematics of a missile named 9M729, but claimed its range was less than 500 kilometers, or about 311 miles (TASS 2019g). However, a US intelligence report on the display subsequently concluded that the event was a hoax: Neither the missile, nor its launch vehicle, nor the schematics shown were what Russia claimed them to be (Panda 2019b). The Trump administration in February 2019 formally announced that the United States would withdraw from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty effective in six months (US State Department 2019b). On August 2, 2019, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty officially died.

The first two 9M729 battalions were deployed in late 2017 (Gordon 2017), and US intelligence sources indicated in December 2018 that Russia had deployed four battalions in the Western, Southern, Central, and Eastern Military Districts with nearly 100 missiles (including spares) (Gordon 2019). We estimate that these four battalions are co-located with the Iskander sites at Elanskiy, Kapustin Yar (possibly moved to a permanent base by now, possibly in the Far East), Mozdok, and Shuya.

It is unknown if Russia has added 9M729 battalions beyond the four reported in December 2018. There is no public confirmation that it has, but in February 2019, only a few weeks after Russia acknowledged the existence of the 9M729 but claimed its range was legal, the press service of Russia’s Western Military District reported it had carried out “electronic launches” of the 9M279 in the Leningrad region (RIA Novosti 2019). This could indicate the 9M729 has been added to a fifth brigade: the 26th Missile Brigade outside Luga about 125 kilometers (about 78 miles) south of St. Petersburg. And in December 2019, Izvestia reported that the Russian military planned to add a fourth battalion to each existing Iskander brigade, each of which previously comprised three battalions of four launchers each (each launcher carries two missiles and probably two reloads) (Izvestia 2019). It remains to be seen if this means that 9M729 launchers will be added to all of Russia’s 12 Iskander brigades; however, in October 2020 Putin declared his willingness to impose a moratorium on future 9M729 deployments in European territory, “but only provided that NATO countries take reciprocal steps that preclude the deployment in Europe of the weapons earlier prohibited under the [Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces] Treaty” (Russian Federation 2020b).

Notes

- We estimate that Russia stores its nuclear weapons at approximately 40 permanent storage sites across the country, including about 10 national-level central storage sites (Kristensen and Norris 2014, 2–9). Essential references for following Russian strategic nuclear forces include the general New START aggregate data that the US and Russian governments release biannually; BBC Monitoring; Pavel Podvig’s website on Russian strategic nuclear forces (Podvig n.d.); and the Russia profile maintained by the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies (2018) on the Nuclear Threat Initiative website. ↑

- For examples of such analyses, see Sokov (2020); Oliker (2018); Tertrais (2018); Oliker and Baklitskiy (2018); Bruusgaard (2016, 2017). ↑

- Three Typhoon-class (Project 941) submarines also remain afloat. One has been converted to a missile test platform. None of these submarines carries nuclear weapons. ↑

- One normally well-informed source says there are no nuclear gravity bombs for the Tu-95MS and Tu-160 aircraft (Podvig 2005). ↑

- Russia is also adding conventional cruise missiles to its bomber fleet, a capability that was showcased in September 2015 when Tu-160 and Tu-95MS bombers launched several long-range conventional Kh-555 and Kh-101 cruise missiles against targets in Syria. New storage facilities have been added to Russia’s bomber bases over the past few years that might be related to the introduction of conventional cruise missiles. ↑

- A US government telegram stated in September 2009 that Russia had “3,000–5,000 plus” nonstrategic nuclear weapons (Hedgehogs.net 2010), a number that comes close to our estimate at the time (Kristensen 2009). The US deputy undersecretary of defense for policy, James Miller, stated in 2011 that nongovernmental sources estimated Russia might have 2,000 to 4,000 nonstrategic nuclear weapons (Miller 2011). For a more in-depth overview of Russian and US nonstrategic nuclear weapons, see Kristensen (2012). Some analysts estimate that Russia has significantly fewer warheads assigned to nonstrategic forces (Sutyagin et al. 2012). ↑

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This research was carried out with grants from the John D. and Katherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Nuclear Notebook, Russia, Russian nuclear arsenal, nuclear arsenal, nuclear risk, nuclear weapons

Topics: Nuclear Notebook, Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons