“When it comes to Russia, it’s like living in a volcano” — Interview with Farida Rustamova, an independent reporter in Putin’s Russia

By Dan Drollette Jr | September 8, 2022

“When it comes to Russia, it’s like living in a volcano” — Interview with Farida Rustamova, an independent reporter in Putin’s Russia

By Dan Drollette Jr | September 8, 2022

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

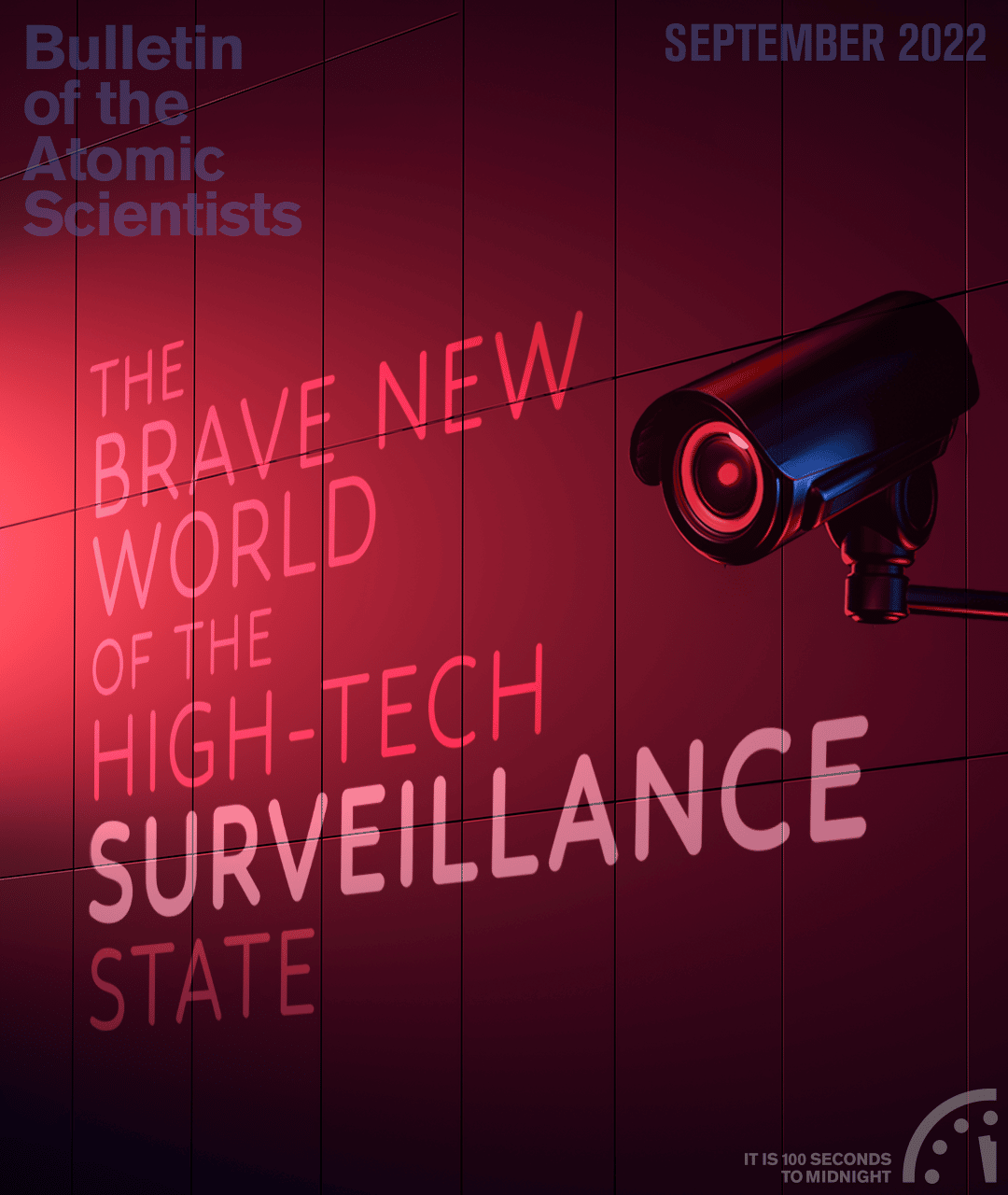

Keywords: Putin, Russia, Ukraine, authoritarianism, democracy, digital repression, dissent, human rights, surveillance

Topics: Interviews