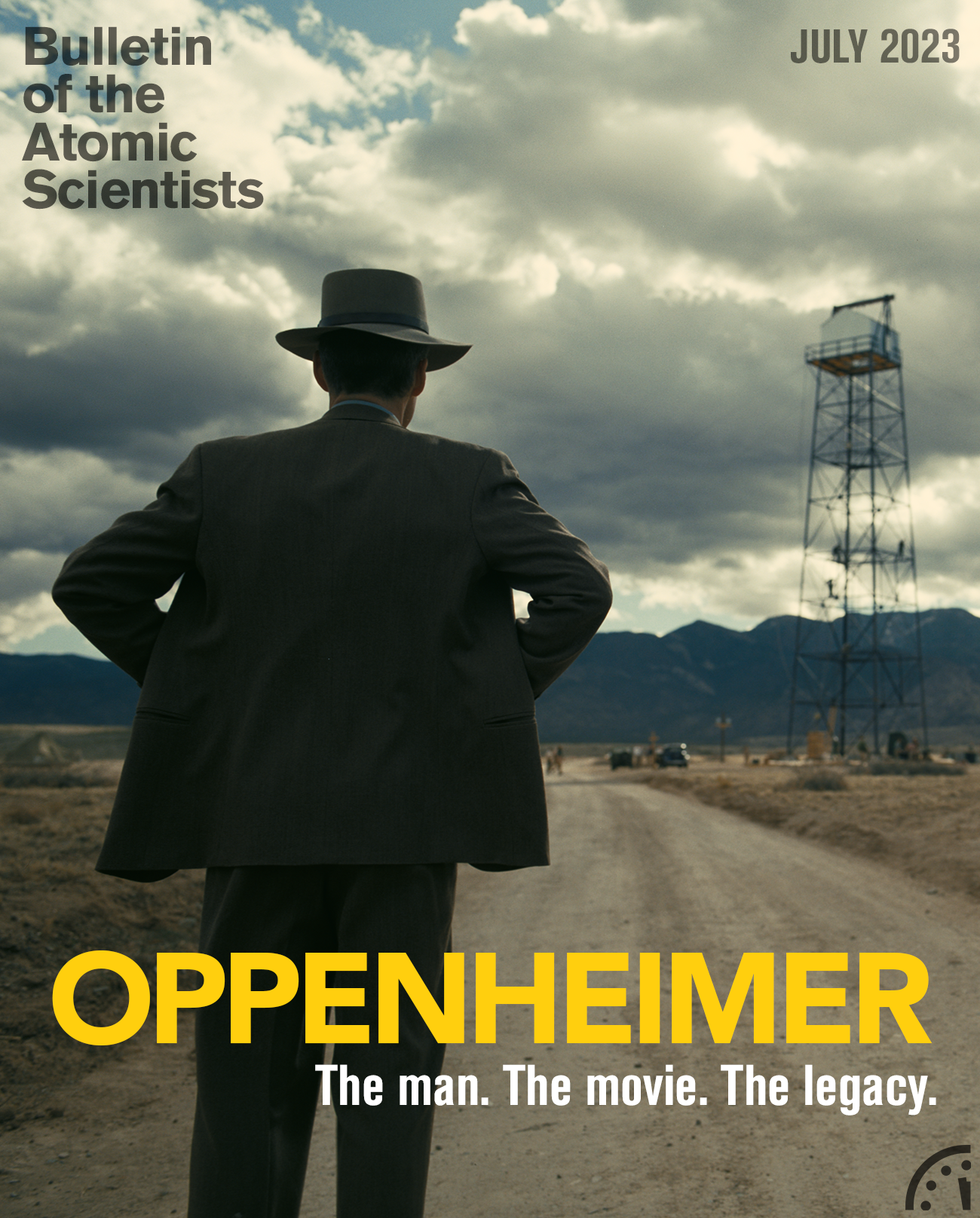

An extended interview with Christopher Nolan, director of Oppenheimer

By John Mecklin | July 17, 2023

An extended interview with Christopher Nolan, director of Oppenheimer

By John Mecklin | July 17, 2023

In the middle of May, I drove to Universal Studios Hollywood and proceeded, per instruction, to Jurassic Parking (yes, that really is the name of the parking garage). I then walked down the Citywalk “street” to the Universal Cinema AMC theaters, where I watched a five-minute montage edited from the soon-to-debut Christopher Nolan film Oppenheimer.

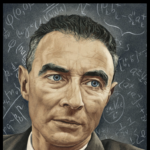

The film clip was brisk and intriguing but not particularly revealing as to plot, so you don’t have to worry about reading further into this piece; I have no spoilers to offer (though I can say Matt Damon plays a mean Gen. Leslie Groves). After the screening, I drove to a leafy and placid part of Hollywood and what appeared to be a converted residence that serves as a cutting studio, where I spoke with Nolan about how he came to choose J. Robert Oppenheimer, the enigmatic director of the Los Alamos laboratory that birthed the atomic bomb, as the subject of a mass-market film.

For those not up on their recent Hollywood history, Nolan has directed a series of major films over the last several decades—among them Tenet, Dunkirk, Interstellar, Inception and three Batman-related films known as The Dark Knight trilogy—that have featured complex narrative approaches and achieved remarkable success, commercial and critical. (Nolan’s films are said to have earned more than $5 billion in the global box office and won 11 Oscars, among 36 total Academy Awards nominations).[1]

Even taking the wide range of his previous work and predilection for innovative storytelling into account, Oppenheimer seems an ambitious choice of subject. The story of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the so-called father of the atomic bomb, certainly doesn’t lack for historical sweep. Oppenheimer was a key figure in the revolution in physics that started in December 1938, when physicists Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch[2] found that something previously thought impossible was actually happening: a uranium nucleus had split in two. Subsequent theorizing and experimentation led scientists to confirm that a chain reaction of such atomic “fissions” was possible. And that such a chain reaction could lead to a massive release in energy, dwarfing what conventional explosives produce.

The race to build an American atomic bomb before Nazi Germany could acquire one is, in its own right, a complicated and existential drama of the highest order. Many of the top physicists at Los Alamos had earlier fled the Third Reich; they knew Werner Heisenberg and other scientists in the emerging field of quantum mechanics had stayed in Germany and worked on a Nazi bomb (though how faithfully later came into question). Beyond the gargantuan task of building a secret laboratory in an isolated part of New Mexico, attracting top scientists to it, and managing their quirky and sometimes conflicting personalities, the Oppenheimer saga includes a variety of complex personal, psychological, and political strands. A polymath seemingly as interested in psychotherapy, poetry, Eastern religion, the arts, and horseback rides across the New Mexican outback as in physics, Oppenheimer was both a commanding figure—a hero of sorts to many at Los Alamos—and a sensitive, ambiguous soul of some fragility.[3]

After education at Harvard, Cambridge, and the University of Göttingen in Germany during the 1920s, Oppenheimer grew to become a major figure in US and world science as he built a physics program at the University of California, Berkeley, along with a joint appointment at the prestigious California Institute of Technology, or Caltech. His contributions to theoretical physics were important across several of its subfields, from quantum field theory to the phenomena that came to be called black holes. In California in the 1930s, Oppenheimer also developed an interest in left political causes. His membership in progressive circles that contained members of US communist and socialist groups was not particularly unusual in the context of a great depression then ravaging the US working class and the rise of fascism in Europe. Many American intellectuals on the political left felt some connection with the Soviet Union, especially as regards its support of the Republican government in the Spanish Civil War, against the fascist Nationalists of Gen. Francisco Franco.

Oppenheimer always maintained that he had never belonged to the Communist Party or taken direction from it, and the public record contains little documentary evidence to the contrary. Still, because of his interactions with a variety of people who were members of the party and allied groups, Oppenheimer became a focus of FBI surveillance and wiretapping well before he was appointed director of the Los Alamos lab.

After the war, Oppenheimer and other scientists involved in creating the first atomic bombs feared that political leaders did not fully appreciate the danger they posed. In hopes of avoiding a global nuclear arms race, some of those scientists, including Oppenheimer,[4] advocated placing nuclear technology under international control (an effort that failed, at least in the short term). A group of Manhattan Project scientists and engineers also focused on wider public education on nuclear weapons and energy (and science generally) through the creation of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists; Oppenheimer served as the first chair of the magazine’s Board of Sponsors.[5]

As the atomic bomb’s so-called father, the porkpie-hatted, cigarette-smoking Oppenheimer became a scientific celebrity in the post-World War II years, serving as director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton and appearing on the covers and in the pages of major magazines. But in 1953, a former congressional aide alleged to the FBI that Oppenheimer was a Soviet spy, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered that a “blank wall be placed between Dr. Oppenheimer and secret data.”[6] Oppenheimer challenged the suspension of his security clearance, but after 19 days of highly publicized hearings, a panel of the Atomic Energy Commission’s Personnel Security Board ultimately refused to reinstate the clearance, effectively ending Oppenheimer’s government service.[7]

It was a decision that haunted Oppenheimer until his death in 1967, and one that was not rescinded until December 2022, when Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm vacated the order that stripped Oppenheimer of his security clearance “through a flawed process that violated the Commission’s own regulations. As time has passed, more evidence has come to light of the bias and unfairness of the process that Dr. Oppenheimer was subjected to while the evidence of his loyalty and love of country have only been further affirmed.”[8] Decades after the fact, records of the Oppenheimer security hearing made it clear that, rather than any disloyalty to the nation, it was his principled opposition to development of the hydrogen bomb—a nuclear fusion-based weapon of immensely greater power than the fission weapons used to decimate Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945—that was key to the decision to essentially bar him from government service.

So the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer is rich, nuanced, dramatic, politically fraught, existentially important, morally challenging—and therefore a narrative that stands out against the general run of animated superhero sequels and other Hollywood franchise fare as starkly (to my way of thinking) as Raymond Chandler’s tarantula on an angel food cake. In the following interview, I asked Nolan how he came to choose Oppenheimer as the subject of a movie and how he went about boiling down the physicist’s sprawling life—as laid out in Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s 700-plus-page, Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, American Prometheus—into a manageable film script.[9] His answers constitute a cinematic origin story of sorts, and one that seemed, to me, both important and interesting during the interview and, on subsequent review, even more worthy of thoughtful attention, as Russia’s sporadic threats of nuclear weapons use in Ukraine continue.

John Mecklin: I work in a field where the material is naturally off-putting; nuclear weapons are not something that people want to talk about. So, the first thing I am interested in is: How did you come to choose Oppenheimer as a movie? It’s not Batman or something.

Christopher Nolan: No, it’s something that’s been on my radar for a number of years. I was a teenager in the ‘80s, the early ‘80s in England. It was the peak of CND, Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, the Greenham Common [protest]; the threat of nuclear war was when I was 12, 13, 14—it was the biggest fear we all had. I think I first encountered Oppenheimer in that relation; I think he was referred to in Sting’s song about the Russians that came out then and talks about Oppenheimer’s “deadly toys.” He was part of the pop culture then, without us knowing a lot about him.

And at some point, in the intervening decades, I got ahold of the information, the fact that the scientists at Los Alamos at a point had determined there was a small statistical possibility that the Trinity test would ignite the atmosphere and destroy all life on Earth. They couldn’t mathematically, theoretically, completely eliminate that possibility; they went ahead anyway. And that struck me as the most dramatic situation in the history of the world, with any sort of possibility being an end to life on Earth. That’s a responsibility that nobody else in the history of the world had ever faced.

I put a reference to that in my last film, Tenet; there’s dialogue, a reference to that exact situation by Oppenheimer. That film deals with a science-fiction extrapolation of that notion: Can you put the toothpaste back in the tube? The danger of knowledge, once knowledge is unveiled—once it’s known, once it’s fact—you can’t wind the clock back and put that away.

So having dealt with that, in a science-fiction sense, at the end of that film, I was sort of left with that as a hanging question. And actually, Robert Pattinson, who’s in Tenet, as a wrap gift, he gave me a book of Oppenheimer speeches, post-World War II speeches. And reading those and reading about the great minds of that time, in the early ‘50s, trying to wrestle with and create some kind of intellectual framework by which to understand and deal with a new existential threat, the first ever truly existential threat to life on Earth—it’s a frightening time to read about, when it’s so new. Then over the decades, we’ve managed to dress it up in all kinds of policy statements, philosophical discussions, you know, all the rest. So, we’ve got generations of people giving intellectual context to the idea of Armageddon, which disguises it and makes it all feel a bit more acceptable as part of the life that we’ve grown up with under the shadow of the bomb. And other than the Bulletin and the Doomsday Clock, [that’s all we have] to remind people of the terrible situation we’re in.

My goal when making the film—I don’t make films to send a message, I made it because it’s a fascinating story. But part of that storytelling is getting back to basics about the bomb, stripping away policy statements, philosophy, the geopolitical situation and just looking at raw power that’s about to be unleashed and what that means for the people involved and means for all of us.

Mecklin: So that was obviously a long runway, a long period of interest. When you sit down to write your screenplay, as I understand, basically based on the American Prometheus book—I mean, that book is 700 pages, and it covers a lot of ground. Just talk a little bit about what the process of getting to a movie is.

Nolan: The process was an interesting one because of everything that makes American Prometheus firstly such a brilliant record of Oppenheimer’s life and interpretation of Oppenheimer’s life. But everything that makes it seem daunting as adaptation is what I found wonderful to adapt, because dealing with real life, with history, and in trying to then make an entertainment from it, an expressive dramatic piece—your biggest hindrance as a screenwriter is authority, is knowledge. I’m not a scientist; I have no way to become a scientist in the period of time it would take me to write the script. You look to experts and expert knowledge.

So, in the past, I’ve collaborated with [Caltech physicist and Nobel laureate] Kip Thorne, for example, on Interstellar and on Tenet. With American Prometheus, Kai Bird and Marty Sherwin (and Marty Sherwin in particular spent 25 years researching the book)—there is an enormous amount of authoritative information, every rock’s been lifted, no stone left unturned. And so, you’re then dealing with an enormous amount of knowledge that, thankfully, has an index at the back. So, once you’ve read it, you can say, “Hang on, what was that bit about [Edward] Teller?” [and] you can look at all the references. And so it was this incredible wealth of knowledge to be able to then start writing a much more subjective script from. I took the view of wanting to tell the story from Oppenheimer’s point of view. That’s what I got from Kai and Martin’s book; I got a feeling of what it is to be this guy, what’s going on in his head. And I felt like that’s the movie.

Mecklin: He’s a tough someone to pin down. I mean, he is ambiguous, shifting, whatever. Did you find that fun to try to put into a movie, or…

Nolan: Yeah, if you look at the films that I’ve made, I’ve always been drawn to ambiguous storytellers, possibly unreliable narrators, people who have interesting layers—those are the characters, right? You know, back to Bruce Wayne, Batman, all the rest, I was interested in characters who in some sense are imprisoned by paradox, who are at the mercy of paradox. And so, for me, it was a very natural fit. And the fact that his story is real, verifiable documentary record, history, really frees you up to just take the audience on the journey. But [for] my interpretation—and ultimately Cillian Murphy’s interpretation of what’s going on in his head, his interior state, which we’re trying to represent—we’ve got a lot of information about where he went, how he got there, what he did.

I’ve always actually favored the medieval, Middle English approach to characterization to the more modern, psychological, novelistic approach to characterization in film, because in film, character defined through action has always been the strongest, because it’s visual, and it’s narrative-based; it’s for me the strongest, most interesting form of building character and characterization. And so, in approaching Oppenheimer, my feeling was by researching, looking at what he said and what he did—where they’re the same, where they’re different—you start to get a sense of the contradictory impulses, and how he dealt with these impossible situations that he was put into.

Mecklin: It’s certainly an open field. In the book, everybody has a slightly different view of who Oppenheimer is. Was he a communist, wasn’t he, all of that. So, I’ll be fascinated to see how he’s handled.

Nolan: He is the ultimate Rorschach test. I believe you see in the Oppenheimer story all that is great and all that is terrible about America’s uniquely modern power in the world. It’s a very, very American story. And there are no simple answers to the questions that it raises, and anyone claiming simple answers to Oppenheimer’s story, let alone to the film itself, is definitely ignoring certain aspects.

Mecklin: These are subjects that deal with physics; physicists are notably persnickety about facts and details. Did you have science advisors along the way, looking at what you’ve done or at the script?

Nolan: I did. We had a very helpful chap from UCLA, David Saltzberg, who was helping us with certain scientific aspects on set. We also brought Kip Thorne into the fold because we’d worked with Kip on a couple of movies. Kip attended Princeton, among other institutions, and while at Princeton went to seminars at the [Institute for Advanced Studies] under Oppenheimer and actually met him; he actually watched him teach. And so I was able to put Kip on the phone with Cillian—and then he visited the set—to talk about what it was like to watch Oppenheimer manage a group of minds in a seminar, how he would organize a debate, how he would apparently listen to all these different points of view and summarize them very, very efficiently and eloquently, and move the dialogue forward.

Kip was also able to answer some of my questions about, for example, there’s a moment where [physicist and subsequently Nobel laureate] Luis Alvarez, [physicist and Nobel laureate] Ernest Lawrence, and Oppenheimer, reading about the splitting of the atom in Germany, apparently then immediately went off and proved on the board that it couldn’t be done. So, of course, we then have to portray it as, “Okay, what does he write on the board?” So, Kip was able to go into it and say, “Okay, this is what we think he may have written. And this is what’s wrong with it; this is where the mistake is, if you like.”

Mecklin: Wow, that’s fascinating. You would think, trying to introduce a general audience to fission, fusion, quantum mechanics, trying to get that into a movie narrative—it must have been some trick.

Nolan: Well, luckily, I’ve had a bit of practice, because my last couple of films have gone in pretty hard on some of the aspects of the science, of the physics, where they create dramatic opportunity. And the thing about fission and fusion, the thing about the revolutionary nature of quantum physics in the 1920s, that’s very dramatic, when you’re dealing with a person’s life. You’re dealing with people who were engaged in a revolutionary reappraisal of the laws of the universe, just as Picasso and other artists were engaged in a revolutionary reappraisal of aesthetic art, of visual representation, just as Stravinsky, you know, was there writing all his music, and indeed, Marx, the communists—that is to say, moving on from Marx, the communist 1920s, the Russian Revolution. I mean, you’re literally rewriting all aspects of the rules whereby we live, physics being the most radical of any of those. So the difference between classical physics and quantum physics is extraordinarily dramatic, even if you can’t understand it.

I can’t explain to the audience—I could barely understand myself—what those differences really constitute, where Einstein’s theory of relativity really takes us. But everybody knows who Einstein is, everybody knows the theory of relativity as a thing that happened, that changed the world. And it lets me position Oppenheimer at the most exciting time in physics, when, literally, the laws of the universe are reappraised and looked at in a completely different way. It’s a paradigm shift that’s, I think, really very unprecedented.

It’s kind of an amazing time. And then, of course, as you start to research and look at the drama of his story and where it then went, where this revolutionary fervor actually wound up—that’s when so many revolutions wound up in a pretty awful place. So trying to give the audience the terms and the grounding, just enough to know that yes, we can’t explain to the audience how quantum physics is different, just that it is radically different.

The difference between fission and fusion becomes very important in terms of the atom bomb versus the hydrogen bomb, how that plays into the politics, the situation where Oppenheimer is, where Teller is. That’s a very relatable human dynamic between the guys interested in fission and the guys interested in fusion and the conflict between them. So I was able, in the screenplay and then the finished film, to build on the sort of pop culture understanding of some of these concepts, because people know the A-bomb, and they know the H-bomb. Do they know the difference between them? No, not really, but that we can explain in the film. So there are lots of ways in which we’re able to dramatize the scientific concepts.

But there are a lot of ways in which—this is what my brother and I found working with Kip on Interstellar—a lot of ways in which the science itself is so dramatic, the theory itself is what’s presenting the possibility of the end of the world, the possibility of enormous destruction, really fearful destruction. These are the most dramatic stakes imaginable. So following the science leads you to some very, very extreme dramatic situations. And as a filmmaker, that’s really what you’re after.

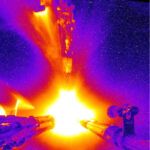

Mecklin: It’s a real departure from the day-to-day ignoring of the ultimate meaning of nuclear weapons. They really could end the Earth, and most people don’t really have a concept of nuclear weapons, or the difference in their sizes. How important was it to you in portraying the Trinity test, or whatever nuclear explosions are going to be portrayed in your movie, and how did you come to the decision about “We’re going to do it [the Trinity test] this way.”

Nolan: The first person we showed the script to after Emma Thomas [my producing partner] was Andrew Jackson, who has been my visual effects supervisor in the last couple movies. Because what I wanted to say to him right out of the gate was, “In this film, we’re going to try and portray the inner state of the character, we’re going to try and show atomic activity, we’re trying to show the quantum world to a degree, which is something that’s unshowable and might obviously lend itself to fancy computer graphics. I don’t want to use any computer graphics for that. We’ve got to show the Trinity test, we’ve got to show the destruction of that; I don’t want to use any computer graphics for that.”

In one of my previous films we portrayed an atomic explosion using CG, and whilst I thought the team did a very good job, and technically the result was good, it confirms to me something that I’ve always felt about computer graphics, which is they tend to feel inherently, in the subconscious of the audience, that they’re animations; they’re not something that’s been photographed in the real world. And so there isn’t really a feeling of danger. And in The Dark Knight Rises, where we have the nuclear explosion, it’s not meant to feel particularly dangerous at the time, because the danger is past, it’s happening out to sea, it’s far enough away.

The point of the Trinity test being there for that birth of atomic weaponry, you want to be terrified. You want it to be beautiful but also frightening, and things that are photographed for real, they’re going to inherently have more weight to them, they’re going to have that threat. Computer graphics tends to feel a bit safer. It’s one thing if the whole film was fanciful. But if the whole film was grounded and real and recognizable as the world we live in, you want this most important event of the film to be equally valid, to have the weight of reality to it. So Andrew thought long and hard about ways in which to photograph real things, both microscopic and macroscopic; he collaborated with our special effects coordinator. Visual effects are the things you do in post-production: optical effects, computer graphics, all those kinds of things that you do after the fact. And special effects are what you do on the floor with the actors, in the moment. Scott Fisher does our special effects, has done for years. He worked very closely with Andrew on some small-scale things to photograph that could be proxies for bigger events and could use the scale of things but also some massive explosions on set that the actors were tied in with; they were there. By using different frame rates and forced perspectives and different combinations of chemicals—magnesium flares in combination with black powder explosions and petrol—to create a variety of explosive effects that could stand in for the Trinity test. Rather than detonating a real atomic bomb, which would be a little extreme (laughs).

Mecklin: Extremely extreme. But it sounds like fun.

Nolan: It was a lot of fun. And they took a very long time to do it. But where their methods became very interesting to me was in the attempts to visualize the quantum world. Because what we were looking for, and what I think we managed to achieve, was a combination of shooting very large things and shooting very tiny things. There is a confusion of scale in the imagery. Are we looking at distant stars and planets or are we looking at atoms and molecules? You don’t quite know; the scales are confused. And to me, one of the most fascinating things about quantum mechanics and everything that’s come from it is this shift between the absolute tiniest things that we know of and the largest that we know of, and both being clearly defined by, determined by, the same set of rules. It’s what’s in the middle that gets a bit complicated, and the interactions between quantum physics and that world in the middle that we all live in, the human-scale world, are some of the most destructive things imaginable. The micro and the macro, the sort of two ends of the scale, I think, are really fascinating.

Mecklin: Do you have any thoughts or expectations about what the response to your movie might be? I know that everybody wants it to be a great success, and you think it’s obviously good. But it really is a touchy subject. Right?

Nolan: I have shown the film to a lot of people by this point; it is a Rorschach test that prompts a variety of responses. There are people who come out of the film literally speechless. They can’t talk; they’re upset in some way. They’ve enjoyed the film, but they don’t understand why they’ve enjoyed it. It’s a very conflicted set of feelings that the film gives you. And that was the goal, that peculiar mixture of emotions, and from the responses so far, we seem to have achieved that. How that fits into the culture, I have no real way of knowing until after it happens. We give it to the audience, and it becomes theirs. What I do know is that, in the history of movies, there are many times in which a complicated emotional response or subject matter can be very powerful for people, can be very entertaining.

Entertaining is a sort of reductive word, we tend to think of that as happy, funny things, whatever, but it’s not. It’s about engagement. It’s about: Does the film resonate with people, do they think about it afterward, do they tell other people to go see it, and that kind of thing? And movies embrace all sorts of different types of engagement. So yes, this is a complicated form of engagement that we’re after. And we’re looking for an extremity of response, an emotional response that’s not necessarily clear-cut. But the film does seem to resonate with people. It does seem to mean something to people. And I think, as a filmmaker, that’s all you can hope for. What that translates to in the culture, we’ll see.

Mecklin: The other current-day question I have is: Obviously, you started this movie well before the invasion of Ukraine. But that invasion has happened since then, and Vladimir Putin and various people in his government have threatened to use nuclear weapons. I’d just like to hear you talk about what you think about your movie being birthed into that current reality.

Nolan: Well, you don’t have any way of knowing the circumstances of the world in which your film will be released, because you started years before. And when I first started writing Oppenheimer, I remember clearly a conversation I had with one of my teenage sons where I told him what I was working on. And he literally said to me, “Well, nobody really worries about nuclear weapons anymore. Are people going to be interested in that?” And, of course, my response to that at the time was, “We should be, and maybe the film would help with that.” But, of course, what then in awful, actual fact has happened is the world has once again been reminded of the threat. Which is, you know, it’s a terrible circumstance. It’s a terrible circumstance. But certainly, our intention with the film—whatever world it was coming out into—absolutely part of the intention of the film is to reiterate the unique and extraordinary danger of nuclear weapons. That’s something we should all be thinking about all the time and care about very, very deeply. But obviously, it’s extraordinarily troubling that the geopolitical situation would have deteriorated once again to the extent that it’s being talked about in the news.

Mecklin: Well, I appreciate you taking all this time to talk to me. So, I think I will turn to a final question: Did anything about making the movie change your mind, change how you think about nuclear weapons? Did it make you more, or less, or the same concerned about this world situation?

Nolan: It’s a hard question to answer. I think the honest answer is that, the deeper into the research I got, and the more that we all talked and thought about it, there’s a phase in which the more you know about nuclear weapons, you start to see them as more ordinary armaments. Because you’re comparing, for example, atomic munitions with hydrogen weapons, so you’re starting to engage in the slippery slope of looking at the scale of things, and how many people were killed by this particular device, you’re starting to get used to the analysis of these things.

Mecklin: You’re normalizing the killing of tens of thousands of people.

Nolan: You’re normalizing killing tens of thousands of people. You’re creating moral equivalences, false equivalences with other types of conflict, et cetera, et cetera. So, you’re going down a lot of different roads toward a more accepting, normalizing of the danger. But then that ultimately leads you around to: That’s the real danger. And that’s when, you know, even Oppenheimer himself, when you start talking to the Army about let’s bring battle back to the battlefield and start talking about tactical nukes—that’s the conversation that I now am most afraid of, because I hear that from both sides of the political spectrum, not just from Putin. I feel we’re in a world now where people are starting to once again talk about those things as some kind of acceptable possibility for our world. And, of course, if we want to think about how nuclear Armageddon ultimately is probably going to happen, is it going to be some Dr. Strangelove-type scenario with bombers getting the wrong signal? I think it’s far more likely to be the normalizing of atomic weapons at the beginning, the use of tactical nukes leading to larger- and larger-scale conflict that will ultimately destroy the planet. So yeah, I came away with a different understanding, a different set of fears that ultimately are founded on the same ultimate fear, which is that the world is going to be destroyed by these things.

Endnotes

[1] See https://www.universalpictures.com/movies/oppenheimer

[2] See https://www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/200712/physicshistory.cfm

[3] Mental distress and odd behavior that surfaced during Oppenheimer’s early university studies led one physicist and science historian to write that even later-in-life Oppie, as he was called by colleagues, retained “a vulnerability that ran through his personality like a geological fault, to be revealed at the next earthquake.”

[4] See https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1949/02/the-open-mind/305431/

[5] See https://thebulletin.org/about-us/board-of-sponsors/

[6] See https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00963402.1977.11458398

[7] See https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/opp06.asp

[8] See https://www.energy.gov/articles/secretary-granholm-statement-doe-order-vacating-1954-atomic-energy-commission-decision

[9] See https://www.pulitzer.org/winners/kai-bird-and-martin-j-sherwin

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: American Prometheus, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Los Alamos, Manhattan Project, Nolan, atomic bomb, movie

Topics: Interviews, Nuclear Weapons

I wonder why 50 star flags are showing in the above picture subtiled “Oppenheimer,” written and directed by Christopher Nolan. Image courtesy of Melinda Sue Gordon/Universal Pictures”.

This article, like others in the BotAS, suggests that the development of atomic bomb was purely an American affair, which, of course, it wasn’t. The idea of an atomic bomb using pure U-235 was first conceived by Peierls and Frisch working at the University of Birmingham in England in 1940 having fled Nazi Germany (Pu fission was worked out slightly later by Feather and Bretscher in Cambridge, England also in 1940). The British then formed the MAUD committee and started their “Tube Alloys” project along with the Canadians. The British and the Canadians then brought the Americans in through the… Read more »

Worse, because Nolan is half English. I don’t think it was ignorance, rather a deliberate decision to cut out the British contribution which was essential, and once again, the British are being airbrushed from Hollywood ‘history’.