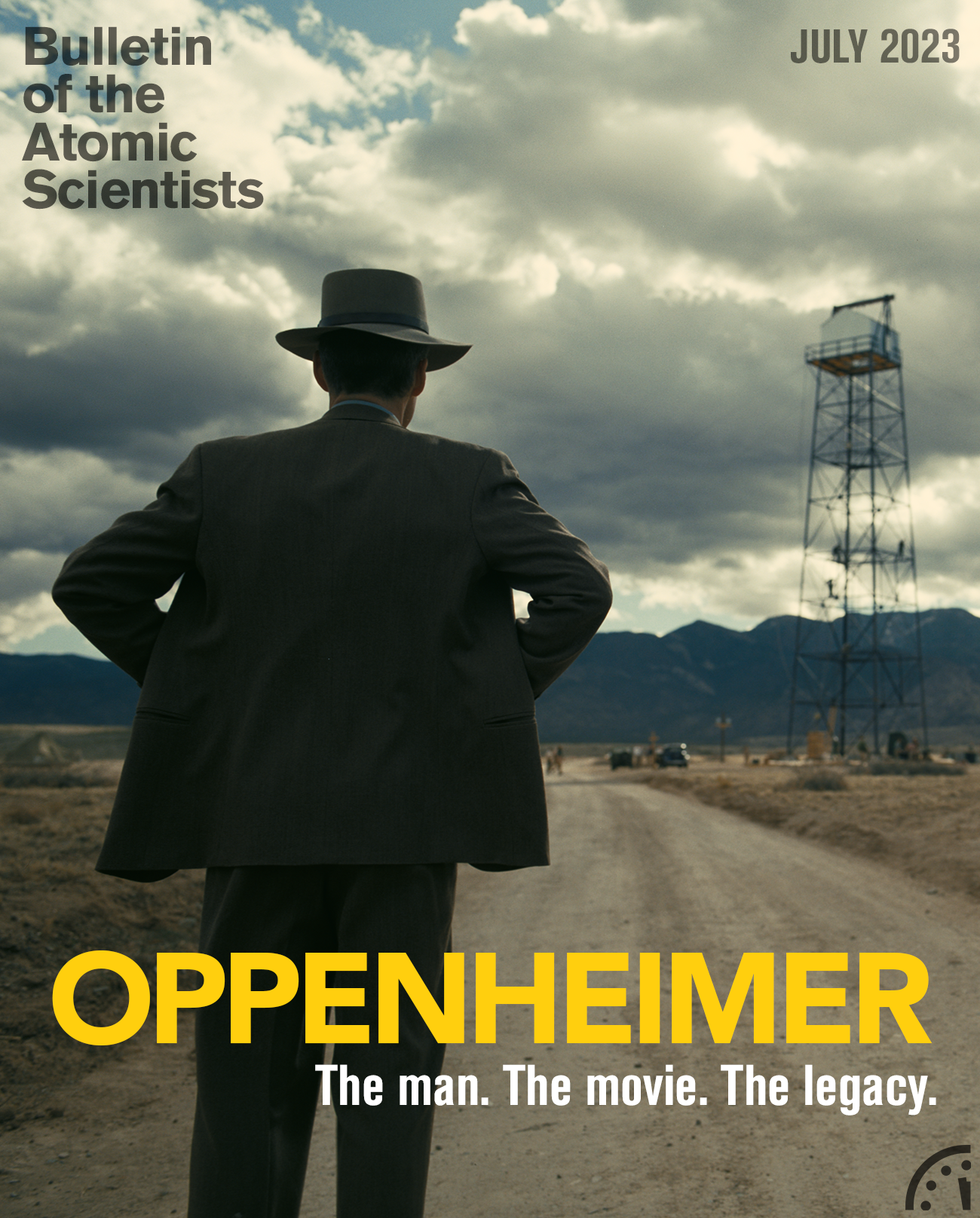

Introduction — Oppenheimer: The man behind the movie

By Dan Drollette Jr | July 17, 2023

Introduction — Oppenheimer: The man behind the movie

By Dan Drollette Jr | July 17, 2023

As this special all-Oppenheimer issue is being wrapped (to use the cinematic term), the release of the major NBC Universal Pictures movie of the same name is still nearly two months away—and what, exactly, will be in it is still mysterious. All that has been seen so far by anyone here at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists are trailers and one five-minute montage. So, even though the magazine itself was founded in 1945 by a group of atomic scientists and engineers, with J. Robert Oppenheimer—the director of the Los Alamos laboratory that built the first atomic bomb—serving as founding chair, we don’t know how the articles chosen for this issue may (or may not) fit in with the film’s narrative arc.

But this very mysteriousness is, in a way, appropriate for the subject matter.

Robert Oppenheimer seems to have been an enigma to all who knew him. By all accounts, Oppenheimer was a complicated figure; over the years, commentators have used words as disparate as “complex,” “contradictory,” “ambitious,” “charismatic,” “mystical,” and “flawed” to describe him. About the only thing pundits seem to agree on is that Oppenheimer—hailed as the father of the atomic bomb before being vilified during the red scare of the 1950s for opposing the subsequent arms race—was brilliant.

One of those who tried to get to the bottom of the man was Kai Bird. Together with his co-author Martin Sherwin, the writing team put in 25 years researching, interviewing, fact-checking, and writing the book that the film Oppenheimer is based upon. In their epic American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer—which won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography in 2005—the duo devoted 599 pages (721 pages including notes, bibliography, credits, and index) to build a nuanced, multifaceted portrait of his essential nature. In his Bulletin interview with me, titled “Oppenheimer: ‘A very mysterious and delphic character,’ ” Bird delves into the personality of “Oppie”—as he liked to be known—his leadership as the head of the scientific end of the effort to build the bomb, his climb to the heights of fame, and his fall from grace.[1]

Bird also describes the recent, and ultimately successful, effort to restore Oppenheimer’s legacy to its rightful place in American society, which culminated in Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm’s decision a few months ago—December of 2022—to vacate the 1954 order stripping Oppenheimer of his security clearance.

This issue also contains an in-depth interview with Christopher Nolan, the acclaimed director of Oppenheimer, by the Bulletin‘s editor-in-chief, John Mecklin. In the interview, Nolan explains his journey to transfer the biography of this polymath from the printed page to the medium of film—and describes Oppenheimer as “the ultimate Rorschach test. I believe you see in the Oppenheimer story all that is great and all that is terrible about America’s uniquely modern power in the world.”

Our Oppenheimer issue also includes a one-on-one interview with physicist and Nobel Prize-winner Roy Glauber—one of the last surviving physicists from the Manhattan Project—who, less than two years before he died, told me his personal impressions of Oppenheimer and the project, obtained when he was an 18-year-old working at Los Alamos. Glauber vividly describes what it was like to be plucked out of his first year of college to work on a secretive government war effort in the middle of the desert, alongside some of the world’s most famous scientists. Glauber also recounts what it was like to witness the bomb’s explosion—which, technically speaking, he wasn’t invited to do.

For more on what drove Oppie, psychiatrist and author Robert Lifton gives his analysis, arguing that Oppie’s greatest tragedy was not the extraordinary “American Inquisition” he underwent as his loyalty was challenged (wrongly, as it turns out) in the 1950s, but the way in which Oppie’s remarkable gifts as a physicist and as a human being were most realized in the building of a weapon that could lead to the destruction of humankind.

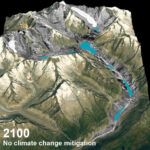

And destructive it was, in more ways than first anticipated. The mushroom cloud set off by the first test of an atomic bomb, at the Trinity site in New Mexico, rose roughly four times higher than anticipated. (Physicists were also not 100-percent sure what would happen when the bomb went off; there were some anxious moments as they calculated whether or not the detonation would set the entire atmosphere on fire.) As investigative journalist Lesley Blume reports, some of the so-called “collateral damage” from the Trinity test were the people who lived downwind from it—nearly half-a-million human beings were living within a 150-mile radius of the explosion, with some as close as 12 miles away. None were warned or evacuated by the US government ahead of time.

To give a deeper sense of events as they occurred in and around J. Robert Oppenheimer, this issue of the Bulletin includes four articles from its archives. The titles alone give a sense of the tale: “Nichols Presents Charges” (1954), “Oppenheimer Replies” (1954), “The Oppenheimer case: A study in the abuse of law” (1977), and “Bulletin statement on the Energy Department’s Oppenheimer decision” (2022).

The articles provide the context and details that those interested in Oppenheimer—the man or the movie—will find nowhere else.

Endnotes

[1] In 1953, a former congressional aide alleged Oppenheimer was a Soviet spy, and President Eisenhower cut off Oppenheimer’s access to classified information. Oppenheimer challenged the suspension of his security clearance, but a panel of the Atomic Energy Commission’s Personnel Security Board ultimately refused to reinstate it, effectively ending Oppenheimer’s government service.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

I read Peter Michaelmore’s book, “The Swift Years: The Robert Oppenheimer Story” in my college days, a half century ago. I then spent my career in the nuclear industry. The story impacted me greatly. Oppie is surely one of the greatest tragic heroes in American history. His story literally changed my life. I have always believed that he should be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, posthumously.

The same interest the military had in smearing Oppenheimer drives “deterrence” today: Oppie was a central figure in a place where big $ was to be made. Idealist, central to 100+ key employees, gifted– of course internal competition got rid of him! Howelse do you maintain a lifetime of $ in a military beurocracy, with no talent?