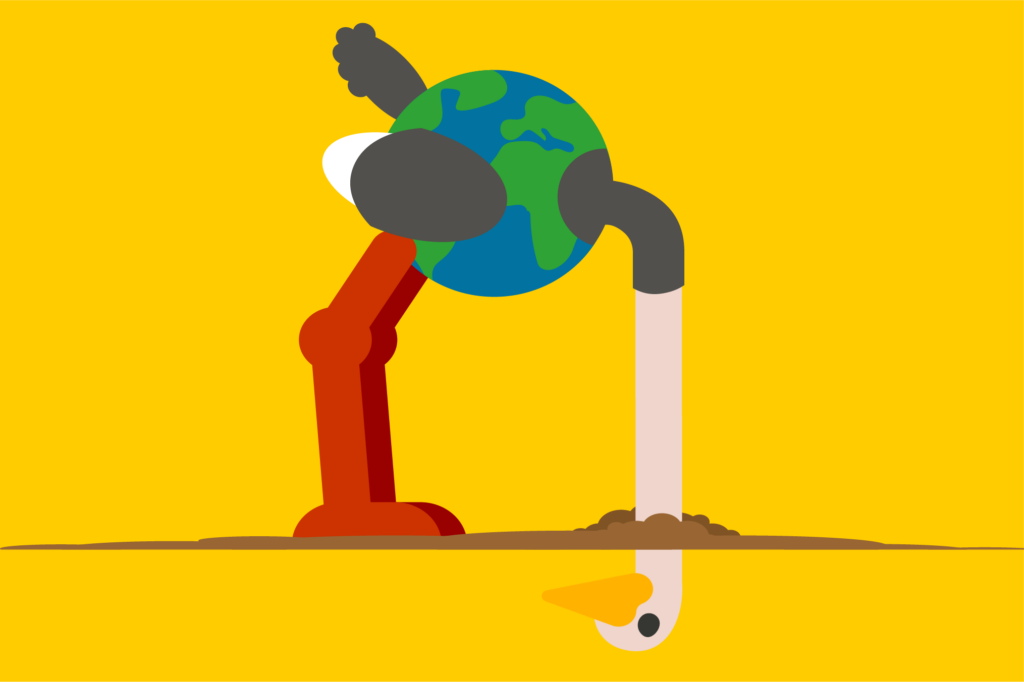

To prevent global catastrophe, governments must first admit there’s a problem

By Rumtin Sepasspour, Courtney Tee | March 25, 2024

Illustration by Thomas Gaulkin / Mary Valery / AonSitthipon

Illustration by Thomas Gaulkin / Mary Valery / AonSitthipon

In January, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists announced that its Doomsday Clock was remaining at an ominous 90 seconds to midnight. The Clock is an annual clarion call for the threats—nuclear weapons, climate change, biosecurity, and disruptive technologies—that, if left unchecked, could destroy humanity. These threats form a combined level of global catastrophic risk, the potential for human death or suffering on a massive scale.

A month earlier, the Global Challenges Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to raising awareness about global catastrophic risk, released their seventh annual report on the risk. It pointed to the same threats as the Bulletin and added “ecological collapse” onto the pile for good measure. The World Economic Forum’s annual Global Risk Report also chimed in: More than half of those surveyed believed that the risk of global catastrophe was high or extreme over the next decade.

Despite these warnings, if one were to turn to government officials anywhere in the world and ask for their view of the risk of global catastrophe, the response would be thunderous silence. These worst-case scenarios receive little attention from policymakers because they are out of the realms of imagination and the time frames of politics.

To properly prevent and prepare for the risk, governments must admit there’s a problem. Such an admission can only come with proper effort to assess and monitor global catastrophic risk, develop potential future scenarios, build and analyze intelligence, and invest in scientific and technical expertise.

Until that happens, governments won’t be able to see beyond their current conceptions of what the future might hold. Such tunnel vision could have catastrophic consequences.

A dose of reality. Should global warming reach an extreme level, an engineered virus be released, unleashing a pandemic, or a football-field-sized asteroid hit Earth, millions—even billions—of people could die. A global catastrophe of this order would also severely cripple humanity. Under such scenarios, food, water, energy, economic, governance, and infrastructure systems are unlikely to recover.

Thinking about calamities of this magnitude can be overwhelmingly terrifying. It is easier to turn away, dismissing the risk as too unlikely to care about or too difficult to properly intervene against. Neither, as it happens, is true.

Governments must step in. They have the resources and mandate to act at the scale that global catastrophic risk demands. Policymakers need to prevent and prepare for the risk of a global catastrophe, especially in a manner that reduces the whole risk collectively. Small actions can have great impact, and those actions are available to any government with the will to take the appropriate steps.

Expanding the mind. For policymakers, issues that are complex, emerging, technical, or chronic tend to receive lackluster attention. Unfortunately, global catastrophic risk is all those things at the same time. Therefore, very little government focus is directed at avoiding the worst-case scenarios that humanity faces.

Although there is some ongoing outside research on the issue, external experts can only help so much. Building a case is fruitless when there is no avid audience within the policy community. Expert efforts to assess the risk from all its various angles is most effective when government itself has the capacity to absorb those assessments.

Governments need to study and conduct research internally, ultimately taking their own steps to understand and assess global catastrophic risk. This should include building a holistic picture of global catastrophic risk, analyzing its various impacts, understanding its drivers, developing monitoring systems that keep tabs on a changing risk landscape, and conceptualizing potential pathways and scenarios for catastrophe.

Properly understanding global catastrophic risk requires clear direction, strong analytical capabilities, and dedicated commitment. Yet, to date, no government has a holistic or a systematic effort towards better understanding global catastrophic risk.

A journey of discovery. Global catastrophic risk can no longer be ignored or be siloed in some dark corner of the bureaucracy. By approaching it via four separate paths, global catastrophic risk can receive whole-of-government attention.

The first is risk assessment: Governments must identify and analyze global catastrophic threats. There is already a blueprint for this kind of assessment in the United States. Passed in 2022, the Global Catastrophic Risk Management Act (GCRMA, 6 U.S.C. §821-825) requires the US government to conduct an assessment of existential and global catastrophic risk. The Global Catastrophic Risk Management Act is the world’s first government-led attempt at properly analyzing the greatest threats bearing down on humanity. Other countries should follow suit.

The second element that can help improve governmental approaches to global catastrophic risk is futures analysis. This could include horizon-scanning, forecasting, and foresight activities. Policymakers must be systematically alerted to emerging trends so that their imagination of what is possible is expanded. The greatest risk to humanity in the next decades may not even be a threat that humans currently have a terminology for. Those governments that have an ongoing futures capability should add global catastrophic risk to the agenda.

The third required element falls into the intelligence and warning category. Governments should develop and allocate intelligence assets to global catastrophic risk, particularly intelligence analysis and collaboration, as previously proposed in the Bulletin. Intelligence and warning for security threats is already an established arm of most governments. There is little reason why some of these efforts could not be regeared and reorientated to consider a wide range of globally catastrophic scenarios.

Lastly, governments should increase their science and research capability so that policy is supported by cutting-edge expertise. Whether increasing internal abilities or focusing academic and research communities’ efforts, understanding and reducing the risk requires access to a breadth and depth of talent.

Incorporating any of these elements will give policymakers a leg up in terms of dealing with global risk. All four, and policymakers will have a rock-solid foundation to prevent and prepare for catastrophe. The utilization of all these parts will ensure governments can prioritize resources and develop well-informed policies that reduce the risk. Such an effort will also support productive collaboration and reasoned communication across society.

Reaching clarity and insight. Governments might listen to external experts and public pressure when it comes to the risk of global catastrophe. But when the call of warning comes from inside the house, it is more difficult to ignore. If publicly available, these government-led assessments and reports are the ammunition that the public and advocates can use to keep governments accountable.

The warning calls are only getting louder this year. The United Nations is conducting a survey of global risk which is expected to be released ahead of the Summit of the Future taking place in late September. The EU Policy Lab–the European Commission’s internal think tank–is conducting their own survey of future risk. The seventh edition of the UK Ministry of Defence’s Global Strategic Trends report is due out this year. And the US-led global catastrophic risk assessment is nearing completion.

These efforts will inch governments closer to a greater understanding of the risk. But it is only the beginning. There is more to discover about the threats humans face and how they can be prevented from becoming catastrophes. As they learn, governments must share the knowledge, internally and throughout society. Ultimately, they must translate their insights into policies that will ensure a global catastrophe is avoided. Collective imagination, wisdom, and action are humanity’s only option.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

The best and perhaps the only practical response to climate and world peace issues is a world government. In other words allow the UN to tax and enforce the conclusions of legal arguments. It means the end of sovereignty for the U.S. government comparable to the way the constitution ended the sovereignty of the state under the articles of confederation. It means UN decisions will be enforced and appealable. U.S. troops would enforce UN orders and the UN would become the sole nuclear power. It might mean the UN issues a world currency. Anyone want to be the next John… Read more »

I like the idea of a world assembly better than a world government. Maybe make the UN Security Council more inclusive of all countries around the world instead of doing a rotation. In fact, perhaps temporarily annul a country’s membership in the Security Council if that country is engaged in a unilateral war for so long as that country is at war, especially one beyond its borders. If a war is being conducted by any country(s) without the democratic approval of the world assembly, then it’s off the Security Council. The only nations that should be on the Security Council… Read more »