Right-Sizing the “Loose Nukes” Security Budget: Part 1

By Kenneth N. Luongo | May 25, 2010

Highlighting the danger posed by nuclear terrorism and the need for an effective response, President Barack Obama came to office promising to “secure all vulnerable nuclear materials around the world within four years.” The necessity of this goal is unquestioned. In fact, since 2004, at least four published official government reports have criticized the adequacy of the U.S. government’s response to the threat of nuclear terrorism. The ability to achieve this objective, however, has been questioned. The Obama administration is in the process of losing a year in its pursuit — its first proposed budget for this initiative fell far short, and Congress did not respond as if securing nuclear materials was an overriding national security priority. In order to meet the accelerated time frame to secure loose nukes around the globe, the president will need to maintain his leadership of the effort in the international community. Equally, if not more important, significant additional funding will be needed from both the United States and multilateral sources.

The Danger. In his April 5th Prague speech, President Obama outlined his arms control and nuclear nonproliferation objectives. At the top of the list was his assessment that terrorists are “determined to buy, build, or steal” a nuclear weapon. The president outlined the following major policy goals to prevent this danger of nuclear terrorism:

- Lead a global effort to secure all nuclear weapons materials at vulnerable sites within four years.

- Convene a nuclear security summit hosted by the U.S. in April 2010.

- Set new standards for nuclear material protection, expand U.S. cooperation with Russia, and pursue new partnerships to lock down sensitive nuclear materials.

- Turn efforts such as the Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) and the Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism into international institutions.

- Build on efforts to break up black markets, detect and intercept materials in transit, and use financial tools to disrupt dangerous trade.

The president’s concern with nuclear terrorism is consistent with a number of recent statements by current and former government officials and published blue ribbon commission reports.1 In reference to weapons of mass destruction (WMD), the 2004 9/11 Commission Report stated that, “Preventing the proliferation of these weapons warrants a maximum effort.” The 2005 9/11 Public Discourse Project: Final Report on the 9/11 Commission Recommendations gave the implementation of that recommendation a “D” grade. It further stated that not only should the president “dramatically accelerate the timetable for securing all nuclear weapons-usable materials around the world and request the necessary resources to complete this task,” but that Congress should “provide the resources needed.” The 2008 WMD Report Card: Evaluating Policies to Prevent Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Terrorism since 2005 gave a “C” to the prevention of WMD terrorism and called for prioritized funding and the abandonment of a “patchwork” approach to the challenge. The 2008 World At Risk: The Report of the Commission on the Prevention of WMD Proliferation and Terrorism advocated that the U.S. work to gain international agreement on “specific, stringent standards” for securing nuclear materials.

Despite these recommendations and some budget spikes notwithstanding, over the past four years the programs for managing the global nuclear danger have remained relatively static with an overall effort that is still not commensurate with the threat. Unfortunately, this trend continued with President Obama’s fiscal year (FY) 2010 budget. The president’s request was even less than the budget that was appropriated for FY 2009 and not sized to meet his ambitious goal. This fact has been acknowledged on and off the record by Obama administration officials.2 The out-year budgets promise to be larger than the FY 2010 budget submission and show significant growth, but not for all relevant programs.

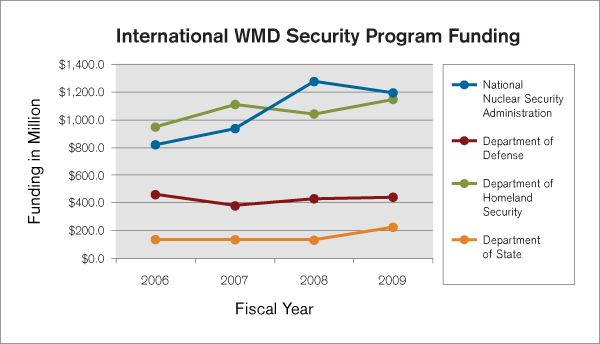

The Budget Trends. The primary agencies that are assigned responsibility for the security of WMDs are the Defense Department, State Department, Department of Homeland Security, and the Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA). The chart below shows the trend in the funding for WMD security programs for each of these agencies from FY 2006-09. Mostly, the trend has been steady during this period, with NNSA’s budget spiking in FY 2008.

Source: Partnership for Global Security

Another important trend is the evolution of the overall budget. In the early and mid-1990s, the budgets for these agencies were focused primarily on nuclear security in Russia and the former Soviet states. The portion of the budget for this region across agencies has shifted in recent years, however, and is projected to drop significantly, especially if Congressional instructions to draw down that funding remain intact. In addition, particularly in both the Defense Department and State Department, the focus appears to have turned from nuclear challenges to defeating biological threats around the globe.

NNSA has emerged as the most important agency in the nuclear material security area. The key programs in NNSA are the International Nuclear Material Protection Cooperation (INMPC) and the Global Threat Reduction Initiative (GTRI) programs. The INMPC program, which focuses on nuclear material protection and accounting at vulnerable sites around the globe, has existed since the mid-1990s. The GTRI program, which focuses on securing and removing dangerous nuclear and radiological materials, was created in 2004 by banding several existing programs together and then expanding their missions and accelerating their objectives.

A comparison of these programs’ budgets for the last five years (FY 2006-10) shows that the INMPC program received an aggregate appropriation of $2.6 billion and the GTRI program less than half that amount at $1.13 billion. However, while the GTRI program has grown relatively steadily, and in FY 2009 substantially, the INMPC program has been on something of a budgetary rollercoaster since its inception and has never again reached its FY 2008 high point of $625 million.

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonproliferation and International Security | $95.0 | $95.0 | $150.0 | $150.0 | $187.2 |

| International Nuclear Materials Protection and Cooperation | $422.7 | $521.7 | $624.5 | $455.0 | $572.1 |

| Elimination of Weapons-Grade Plutonium Production | $174.4 | $174.4 | $179.9 | $141.3 | $24.5 |

| Fissile Materials Disposition | $34.2 | $34.2 | $66.2 | $41.8 | $36.4 |

| Global Threat Reduction Initiative | $97.0 | $115.5 | $193.2 | $395.0 | $333.5 |

| Other Appropriations (not program specific) | $0.0 | $0.0 | $56.9 | $1.9 | $0.0 |

| TOTAL | $823.3 | $940.8 | $1,270.7 | $1,185.0 | $1,154.0 |

Also, the INMPC budget has been split between the “first line of defense” against nuclear dangers (the protection of the materials at their source) and the “second line of defense”, which focuses on border and port security. In fact, the second line of defense programs have grown to about 45 percent of the INMPC budget. The remainder of the INMPC program focuses primarily on nuclear security in Russia and the former Soviet states, with activities in other countries like China filling out the balance. By contrast, about 35 percent of the GTRI program focuses on Russia and the former Soviet states.

Budgeting for the Four-Year Pledge. Given the high priority that the administration has placed on securing all vulnerable nuclear materials in four years, its FY 2010 budget request was inadequate, though this can partially be explained by the challenges created by the transition between administrations. But the actions of Congress on this budget request and the lackluster effort by the administration to lobby for increased funds has left the overall nuclear security budget below the FY 2009 level. While there was a boost given to some programs, in reality the administration is in the process of losing a year of its four-year pledge.

Among the major congressional committees that deal with nuclear security, only the House Armed Services Committee (HASC) provided any significant programmatic increases. For example, that committee increased the INMPC program’s budget by almost $200 million. Further, the committee increased the GTRI budget by over $200 million, which includes $126 million specifically for the development of a four-year nuclear security plan. The HASC also boosted the budget for the Defense Department’s Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) program by $30 million. All told, this was roughly a $430 million increase that would have provided the administration with funds to front-load their efforts to secure nuclear materials.

Unfortunately, other committees did not consider the issue as urgent as the HASC. When the final appropriations bill was signed into law in late October, the INMPC program received a $20 million boost, while GTRI’s funding was cut by $20 million. However, within GTRI, the final bill did usefully increase funding for the conversion of research reactors to low-enrich uranium fuel by $20 million.

Administration officials have stated behind the scenes that the budget for FY 2011 and beyond will look much different.3 The FY 2010 budget request document previewed their future planning, but it also revealed some serious flaws. The budget projects significant growth for the GTRI program through FY 2014, when it tops out at over $1 billion. But the funding profile is out of balance as the major funding increase does not come until the last year. From FY 2011-14, the projected budget augmentation is about $592 million, but $356 million of that funding increase is projected to be provided in FY 2014. This curve needs to be evened out and more funding provided at the front end.

Conversely, the INMPC budget is projected to stay relatively flat from FY 2011 through FY 2014. Most significantly, the budget assumes that funding for nuclear security in Russia and the former Soviet states will drop to around $50 million after FY 2012. These funds would be used to consolidate nuclear materials at fewer locations and sustain the security improvements that have been put in place over the past two decades. This ramp-down is based on congressional direction that these programs be ended, but it does not reflect the reality that work must still be done in these countries after 2012. If this budget profile holds, the INMPC program would be almost entirely a second line of defense effort by the end of the administration’s four-year term.

| Program | FY 20115 | FY 2012 | FY 2013 | FY 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| International Nuclear Materials Protection and Cooperation | ||||

| Navy Complex | 42.4 | 31.8 | 0 | 0 |

| Strategic Rocket Forces | 44.9 | 37.8 | 0 | 0 |

| Rosatom Weapons Complex | 103.5 | 52.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Civilian Nuclear Sites | 24.8 | 18.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Material Consolidation and Conversion | 14.2 | 14.3 | 14.6 | 14.6 |

| National Programs and Sustainability | 62.1 | 62.0 | 39.0 | 39.0 |

| Second Line of Defense Program | 291.4 | 354.4 | 508.2 | 504.9 |

| Subtotal, INMPC | $583.4 | $570.8 | $561.8 | $558.5 |

| Global Threat Reduction Initiative | ||||

| HEU Reactor Conversion | 105.0 | 189.0 | 193.0 | 299.0 |

| Nuclear and Radiological Material Removal | 278.5 | 328.0 | 356.0 | 491.0 |

| Nuclear and Radiological Material Protection | 97.7 | 135.2 | 168.3 | 283.0 |

| Subtotal, GTRI | $481.1 | $652.2 | $717.3 | $1,073.0 |

| TOTAL | $1,064.5 | $1,223.0 | $1,279.1 | $1,631.5 |

Recommendations. As a first order of business, the administration should correct the FY 2010 budget shortfalls by proposing increases in a supplemental appropriations request of $115 million. At the very least, the cut to the GTRI program should be reversed and its funding restored to the FY 2009 level of $395 million (an addition of $62 million). Similarly, the INMPC budget should be closer to $625 million (an addition of about $53 million).

In addition, the congressional limit on nuclear security spending in Russia and the former Soviet states beginning in FY 2012 needs to be modified so that the programs can continue. This is especially important not just because the job will not have been completed by that date, but also because security equipment installed at the start of this cooperation in the early and mid-1990s is nearing the end of its life expectancy and is becoming obsolete. Improvements on the original security measures, therefore, may be required. Also, the first and second lines of defense missions likely will grow in other countries over the next several years.

In addition, the radiological security mission should be boosted. Recent news reports, about terrorist activity in the United States make clear that the danger has not passed.6 A large number of radiological sources exist in the United States, and many are in public buildings. An even larger number of these sources can be found abroad. As a result, the challenge of securing all radiological materials is significant, but it can seem too unwieldy. The administration, however, at the very least, should commit to secure all the radiological sources in public buildings, beginning with major metropolitan hospitals, in the U.S. on an accelerated timetable.

Looking forward, in order to accomplish the president’s four-year goal, a more realistic budget for both the INMPC and GTRI programs needs to be constructed. For INMPC, FY 2011 funding should be about $650 million and then, on average, grow to about $700-$750 million per year for FY 2012-14. This level of funding would allow INMPC to sustain its current work in Russia and the former Soviet states while supporting its ability to respond to emerging threats in other nations and regions. Half of this funding could be directed to nuclear security improvements in Russia, the former Soviet states, and other regions and countries of concern. The other half of the funding could be used for the second line of defense. In order for GTRI to accelerate the removal of high-priority nuclear and radiological materials and meet its research reactor conversion objectives, its FY 2011 budget should be in the $550-$600 million range. It should then grow to about $700-$750 million per year for FY 2012-14. This would reduce some of the bubble-like growth in the program’s currently projected FY 2014 budget and allow it to ramp-up its activities more effectively in support of the president’s objectives.

Conclusion. Within three months of taking office, President Obama committed the United States to one of the most essential and ambitious policies for protecting the globe from nuclear terrorism. Securing all vulnerable nuclear material in four years is a necessary objective and maximum effort must be made to achieve it, both in the United States and internationally. However, the administration’s strong political commitment has not been matched with adequate resources at home or abroad. The administration should seek a supplemental appropriation for FY 2010 to overcome the current funding deficit. Then it should increase and refine its out-year budgets for key programs. In addition, the world’s wealthiest nations must expand their global nuclear security efforts and collectively match the spending of the United States. Only with the fusing of political commitment and adequate financing can the mission of securing all vulnerable nuclear and radiological materials on an accelerated timetable be accomplished.

1 See for example Robert Gates, “Nuclear Weapons and Deterrence in the 21st Century,” speech at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington, D.C., October 28, 2008, available at http://www.carnegieendowment.org/files/1028_transcrip_gates_checked.pdf; J. Michael McConnell, “Annual Threat Assessment of the Intelligence Community,” testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee, February 27, 2008, http://www.fas.org/irp/congress/2008_hr/022708mcconnell.pdf; and George Tenet, “The Worldwide Threat 2004: Challenges in a Changing Global Context,” testimony before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, February 24, 2004, available at http://intelligence.senate.gov/040224/tenet.pdf.

2 According to the transcript of the May 21, 2009 House Appropriations Energy and Water Subcommittee, Cong. Chet Edwards, Democrat of Texas, asked NNSA Administrator Thomas D’Agostino, “So to just be clear on that key point, the budget numbers coming out of the administration for fiscal year 2010 were put together before the four year plan was–was proposed and the cost implications of it were fully considered. Is that correct?” D’Agostino replied, “That’s correct, sir.” In that same hearing, Ken Baker, NNSA’s acting deputy administrator for defense nuclear nonproliferation, also testified that, “It will take a lot more money to do the four-year plan.”

3 Private communications between the author and Obama administration officials in 2009.

4 Energy Department, “FY 2010 Congressional Budget Request, National Nuclear Security Administration,” May 2009, DOE/CF-035, vol. 1, pp. 389, 444, available at http://www.cfo.doe.gov/budget/10budget/Content/Volumes/Volume1.pdf.

5 Some line items do not add exactly due to rounding.

6 For further examples see Abby Goodnough and Liz Robbins, “Mass. Man Arrested in Terrorism Case,” New York Times, October 21, 2009, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/22/us/22terror.html; FBI, “FBI Arrests Jordanian Citizen for Attempting to Bomb Skyscraper in Downtown Dallas,” Department of Justice press release, September 24, 2009, http://dallas.fbi.gov/dojpressrel/pressrel09/dl092409.htm; and FBI, “Three Arrested in Ongoing Terror Investigation,” Department of Justice press release,September 20, 2009, available at http://www.fbi.gov/pressrel/pressrel09/zazi_092009.htm.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Nuclear Weapons, Opinion