“The new retirement” for nuclear power plants

By Dawn Stover | April 26, 2012

America’s senior citizens once dreamed of moving to a beach house in Florida or touring the nation’s parks in a motor home when they turned 65. But the global financial crisis has taken a heavy toll on retirement plans. During the past four years, many seniors have watched helplessly as their homes plummeted in value and their 401(k) savings plans became 201(k)s.

Today, only 14 percent of Americans age 25 and older are confident that they will have enough money to retire comfortably, according to a recent survey by the Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI). Another recent survey, by Wells Fargo, reported that a quarter of middle-class Americans now plan to postpone retirement until they are at least 80 years old — longer than many of them are expected to live. For Americans facing an uncertain financial future, 80 is the new 65.

Some are calling it “the new retirement.” But it really should be called “the no retirement.”

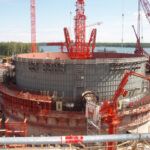

And senior citizens aren’t alone. Nuclear reactors are experiencing some of the same woes: Retirement age is fast approaching or already in the rearview mirror, but there is a lot less money in the nest egg than anticipated. At the 44 US nuclear reactors that have already received license extensions, 60 is the new 40. And even when those reactors reach the end of their working lives, they may not be able to move on to the final stage. According to a recent article in The New York Times, the operators of 20 US nuclear reactors — including some with licenses that expire soon — do not have sufficient funding for prompt dismantling. If these reactors can’t keep working, their owners “intend to let them sit like industrial relics for 20 to 60 years or even longer while interest accrues in the reactors’ retirement accounts.”

The challenges ahead for nuclear reactors are much like those that America’s seniors now face in their less-than-golden years. They include:

Insufficient savings. The proportion of American workers who have saved for retirement has dropped from 75 percent in 2009 to 66 percent in 2012, according to the EBRI telephone survey of 1,262 individuals. Of these people, 60 percent say they have less than $25,000 in savings (not counting a home or traditional pension plan), and 30 percent say they have less than $1,000. More than half of workers have not even tried to calculate how much money they will need to save before they can retire.

Some reactor operators haven’t saved enough, either. Decommissioning a reactor is an expensive undertaking that involves dismantling large structures and burying their radioactive components in one of the very few sites around the country that will accept them. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) estimates that this process costs $300 million to $400 million per reactor, but other estimates range as high as $1 billion.

Nuclear reactor licensees are required to report to the NRC every two years on the status of their funding and to provide an estimate of the minimum amount needed for decommissioning. About 30 percent of licensees are required to have prepaid funds or some other method of guaranteeing payment, but most licensees — including rate-regulated utilities — are authorized to accumulate decommissioning funds over the operating life of their plants. The problem is that these funds are invested in the same financial marketplace where individual Americans put their savings — which clearly has proved to be an extremely risky environment.

Job insecurity. Many Americans plan to work longer, but there is no guarantee that there will be enough jobs for all of them in this time of high unemployment. Even when jobs are available, they are often low-paying and physically demanding. Seniors who dreamed of relaxing in their RVs may instead find themselves making their way across the country as “workampers,” doing back-breaking seasonal labor in warehouses, or cleaning toilets at campgrounds in exchange for free parking.

Like older Americans, many nuclear reactors may keep on chugging well past their original retirement ages. But if there isn’t enough demand for nuclear power, there is no guarantee that they will be able to do so, either — especially without a carbon tax to lift their job prospects.

Health problems. Although many Americans plan to keep working past age 65, the reality is that retirees are often forced to leave the work force earlier than expected, usually for health reasons. The EBRI survey found that although only 8 percent of workers say they plan to retire before age 60, 40 percent of people who have already retired did so before age 60. And 25 percent retired between ages 60 and 64 — although only 16 percent had planned to do so.

Health problems can cause reactors to retire earlier than planned, too. Of all US reactors that have been completed and brought online, 13 percent have retired before their licenses expired, and another 25 percent have experienced outages lasting longer than a year.

Rising costs. For people who are still employed in their 50s and 60s, income may not be rising in step with expenses — particularly the cost of health care. Many seniors are clueless about how much money they really need to live worry-free.

The same can be true of nuclear reactors, where repairs and retrofits often cost far more than anticipated. In some cases, the cost of decommissioning a nuclear reactor may end up being higher than the cost of building it.

Stifled growth. When older workers stay on the job longer than originally planned, that leaves no room for new workers to fill their shoes. The same is true for nuclear power, where new plants are not being brought online to replace old ones. The result is stagnation at the entry level — for more technically savvy reactors and echo-boomers alike.

Instead of retiring reactors by immediately dismantling them and decontaminating the property so that it can be used for something new, reactor owners may instead choose option number two, known as SAFSTOR (safe storage), in which decontamination is delayed and radioactive waste is allowed to decay on site for decades. (The NRC’s third option for decommissioning a nuclear reactor — entombing it in concrete on site — has never been used at any NRC-licensed facilities.) Extended dry-cask storage has already become the de facto alternative to geologic disposal in the United States, so perhaps it is no surprise that entire power plants — not just spent fuel — may end up in limbo for a century or more.

Is it crazy for someone to delay his retirement past the age he can expect to live? Sure, but that’s essentially what the nuclear industry plans to do with many of its reactors. And it should not come as a surprise that the NRC has no problem with this plan. After all, we’re talking about a regulatory agency that issues 40-year licenses for a process that creates a radioactive waste problem lasting tens of thousands of years.

Time for reform. It is only thanks to Social Security and Medicare that many seniors are able to retire at all. Clearly, we need government reforms that encourage — or force — people to save more and that protect retirement savings from the vagaries of the financial markets; otherwise, we will all bear the burden of caring for unprepared elders. The same is true for reactor decommissioning funds.

It’s not that reactor operators have failed to save for retirement. On October 26, 2011, the NRC issued its staff review of the 2010 decommissioning funding status reports from licensees, which reported that $40.4 billion had been set aside for decommissioning the nation’s 104 reactors. But that might not be enough, especially if nothing more is done to fix our broken financial regulatory system.

Don’t blame the victims. “The no retirement” was not created by lazy workers or irresponsible NRC licensees. It is the result of greedy, deceitful practices at the world’s largest financial institutions — aided by regulators and politicians. Regardless of how hard Americans work and how much they save, market forces continue to control every aspect of their lives, from retirement plans to how much they pay for gas at the pump. And because of these same market forces, some communities can now expect to live with elderly radioactive relics for decades to come.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Columnists, Nuclear Energy