The money behind the Islamic State

By Dan Drollette Jr | July 6, 2014

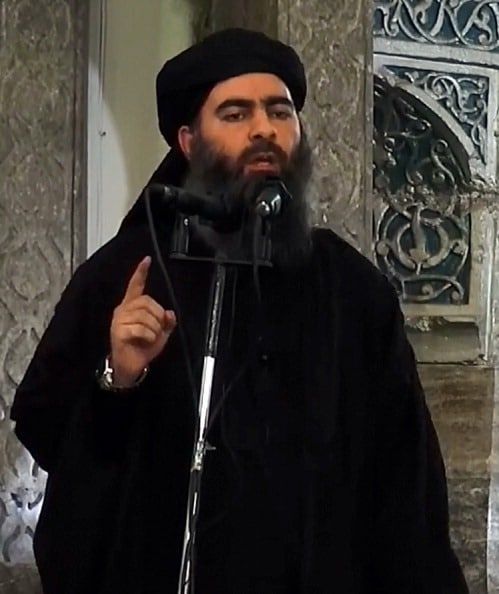

Recent articles about the nature of the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (since renamed simply the Islamic State, or ISIS) are harrowing in their description of the group's ferocity, viz. a BBC article contending it regularly executes “those who are foolish enough to stay behind.” A recent New York Times’ story about the advance of this Sunni jihadist army in Iraq makes the point from a slightly different vantage: “Behind the image of savagery that the extremists of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria present to the world, as casual executioners who kill helpless prisoners and behead even rival jihadis, lies a disciplined organization that employs social media and sophisticated financial strategies in the funding and governance of the areas it has conquered.” In addition, “Its members are better paid, better trained, and better armed than even the national armies of Syria and Iraq,” the leader of an opposing force told the paper. And as Charles P. Blair pointed out in these pages a couple of weeks ago, we should not have been surprised by the appearance of ISIS, as it has been percolating along in the background for a long time, steadily building an infrastructure, gaining adherents, and soliciting all-important financial backers.

One of the problems in assessing the Islamic State involves sorting out exactly who is behind it, financially speaking. Clearly, however, a good portion of the funding for the ISIS—and similar terror groups, such as the Al Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra—comes from Sunni elites located in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the Gulf states, countries that are ostensibly US allies. Under-the-radar funding tactics and lax regulations in the region allow fundraisers to set up small religious charities and ask for money in mosques and other public places, in what The Washington Post describes as “terrorist fundraising.”

This private funding for terror groups puts the United States in a difficult situation, to say the least. The Gulf states are US allies, and suppliers of oil; like the US, they want a new government in Syria. But the US does not want extreme Sunni terrorists to take over that country or continue expanding into Iraq; however, the Kuwaiti, Saudi, and emirati patrons of the Islamic State do not seem particularly worried about such outcomes.

And outside funding for the Islamic State is anything but small potatoes. Hundreds of millions of dollars has flowed into the group's coffers from Kuwaitis, as well as from citizens of Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states solicited from Kuwait.

The Saudi case is especially interesting, given the huge volume of arms sales the US has made to the country over the decades, and the seemingly close alignment of US-Saudi interests—at least, on the surface. Saudi Arabia exported almost 10 million barrels of petroleum a day in 2013, according to the US Energy Information Administration; the United States imported about 1.5 million of those barrels daily. Indeed, the original name of what is now the Saudi national oil company was the Arab American Oil Company, or Aramco, back when it started in the 1940s. But the country’s religious leadership, which promotes a strict form of Islam known as Wahhabism, associated religious schools, and the Saudi populace are all sources for the spread of extremist political Islam, and wealthy Saudi individuals fund jihadists worldwide.

US-Saudi tensions will be familiar to longtime readers of The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. As far back as 1966, Bulletin writer John S. Badeau was commenting about the inherent shakiness of the US alliance with Saudi Arabia, saying: “[The United States] is in the position of supporting governments and systems which we do not like and whose activities frequently cause trouble… Although Saudi Arabia is closely bound to us by a mutual interest in petroleum and in general may be considered, at least for the moment, pro-American, no one would maintain that its royal government is the best of all possible political systems or represents what may be most desirable for the advancement of the country.”

These were strong words, but Badeau knew what he was talking about: He was US ambassador to the United Arab Republic from 1961 to 1964 (when it was Egypt's official name), former president of the American University in Cairo, and at the time of writing the article, director of the Middle East Institute of Columbia University.

His was not the only voice to urge caution. In 1983, Robert Andersen pointed out that “the petrodollars of Libya, Saudi Arabia, and the Gulf states financed Pakistan’s bomb project” in a Bulletin review of the book The Islamic Bomb.

And as long ago as the late 1970s, analysts were worried about the Saudi government’s continuous purchase of arms from the United States, “which it intends quite openly to transfer to Arab ‘confrontation states,’” Yair Evron of Tel Aviv University wrote in these pages in his article, “Arms and Security in the Middle East.” It appears that Evron was right to be worried. If it is not yet widely accepted as a nation, the Islamic State's newly announced caliphate over large portions of Syria and Iraq certainly could be considered a confrontation state.

Editor’s note: The full archive of Bulletin print issues—from 1945 to 1998, and complete with covers and other illustrations—is available here.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Analysis, Nuclear Weapons, Special Topics