The persistence of the radioactive bogeyman

By Andrew Newman | October 23, 2017

As the gigantic ants—mutations born of the first nuclear weapon test in New Mexico—are exterminated by US army flame-throwers in the climactic scene of 1954’s Them!, Dr. Harold Medford reflects: “When man entered the atomic age, he opened the door to a new world. What we’ll eventually find in that new world, nobody can predict.” In the world of horror cinema, however, the results are entirely predictable. Bad and scary things come of meddling with the atom.

Most movie buffs know about Godzilla and Mothra, but the range of radiation-themed horror movies extends far beyond those Japanese monsters. Since 1950, in fact, a remarkable number of American and European horror movies have used radiation as a central plot device. It is a rich, if not distinguished, history. In fact, it is a mostly miserable history, full of bad production values, bad plots, and bad acting. But that doesn’t mean these radioactive B-movies are unimportant. They reflect the fears and misconceptions of their era as they relate to scientific advances—and scientific arrogance.

Horror, science, and radiation. At the beginning of the 20th century, “excited physicists pointed out that for countless ages radium has been emitting heat and light while transmuting, as though it contained the energies of the original creation. When doctors reported that atomic rays could heal they seemed only to confirm that radioactivity meant life-force.” Indeed, as Spencer Weart’s book Nuclear Fear notes, in 1903 a Connecticut newspaper suggested that radium could plausibly raise the dead. Reflecting on his radium-based miniaturization experiments in Dr. Cyclops (1940), Dr. Thorkel declares: “In our very hands we have the cosmic force of creation itself … we can shape life, take it apart, put it together again, mold it like putty.” His colleague, Dr. Mendoza, objects: “But what you are doing is mad. It is diabolic. You are tampering with powers reserved to God.” Thorkel, clearly thrilled by the suggestion, responds: “That is good. That is very good. That is just what I am doing.”

But by 1945, radiation had acquired an even more insidious reputation in the real world. The awful fates of Marie Curie, the “Radium Girls” who died from painting luminous radium paint onto dial faces, steel company president Eben Byers, who died from drinking Radithor, a radium-laced tonic, and the residents of Hiroshima demonstrated the ghastly destruction that this odorless, flavorless, invisible force could wreak on the human body. It did not require a huge leap of faith for moviegoers to imagine that ionizing radiation could also cause miniaturization, gigantism, and terrible mutation.

Horror movies’ primary purpose is to scare the audience, and as a rule, the genre is quite conservative, reinforcing society’s rules and punishing transgressors. Given a deep public ambivalence toward scientific discovery, scientists have been big losers in horror films. In 1950s and 1960s cinema, science experiments were rarely portrayed as nefarious by design. All the same, they were held responsible for some horrific threat manifest in the world—but it was a threat that scientists also had the expertise to combat, usually by destroying the monster (with the help of the military). But by the 1970s, corporate/government/ military conspiracies are the norm; scientists unleash forces they cannot control, and the end of the movie is far from the end of the story.

The atomic monster cycle. The successful 1952 re-release of King Kong (1933) encouraged Warner Brothers to launch the atomic monster cycle film, film critic Kim Newman writes in his book Apocalypse Movies. And audiences loved it. By the mid-1950s, “if it wasn’t atomic and didn’t glow in the dark, it wasn’t going to sell,” Jamie Russell notes in Book of the Dead: The Complete History of Zombie Cinema. With the exception of The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), bigger and angrier was the sure-fire result of irradiation by good, bad, or indifferent scientists.

Scene from The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

In The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953), US nuclear weapons tests in the Arctic wake a 100 million year old “rhedosaurus.” The creature is shot with and killed by a radioactive isotope, providing one of the clearest illustrations of the thin line between nuclear science destroying the world and saving it.

In Them!, Warner’s highest grossing movie of 1954, giant ants leave a trail of death and destruction in New Mexico and, briefly, Los Angeles. However, in what is as close as 1950s horror came to an open ending, Dr. Medford muses: “We haven’t seen the end of them. We’ve only had a close view of the beginning of what may be the end of us”—a fair point to make, given that the United States didn’t conduct its last atmospheric nuclear test until July 1962, with underground tests continuing till September 1992.

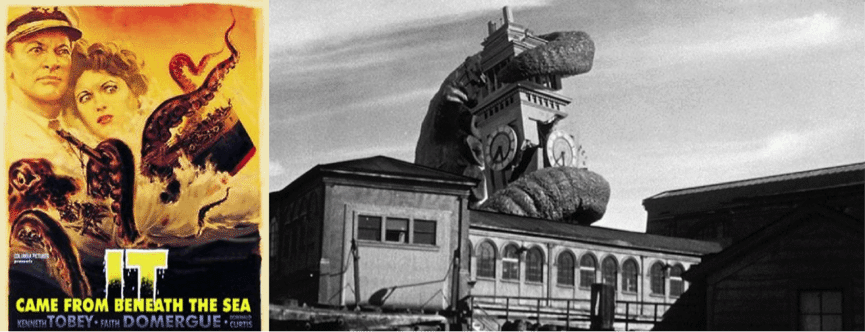

In It Came From Beneath The Sea (1955), a giant octopus causes havoc on the San Francisco waterfront before being blown to bits, hydrogen bomb tests in the Marshall Islands having irradiated the cephalopod and scared off all of the other sea creatures, forcing it to the surface in search of food.

It Came From Beneath The Sea. Photo credit: IMDb

In X the Unknown (1956), a subterranean explosion in the Scottish Highlands releases a blob-like ooze that destroys property and gives several non-essential cast members radiation burns. Conveniently, experiments with fictional radioactive element “trinium” are successful just in time to neutralize the life form. The subversive ramifications are clear: It is now possible to “neutralize” atomic bombs. (A Cold War side note: Film buffs may recall that Joseph Losey, who had fled to London several years earlier when brought to the attention of the House Un-American Activities Committee, directed X for a few days before “falling ill.” Star Dean Jagger’s refusal to work with a communist sympathizer had in fact forced Hammer Films to replace Losey.)

In Roger Corman’s Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957), nuclear testing in the Pacific creates a couple of massive crabs. Any matter they eat is assimilated, enabling the crustaceans to make use of human faculties, such as holding conversations with surviving cast members, who eventually electrocute the last of the monsters.

Attack of the Crab Monsters poster. Photo credit: IMDb

In Beginning of the End (1957), the Department of Agriculture under the direction of a pre-Mission Impossible Peter Graves is using radioisotopes to grow enormous vegetables. But the produce attracts hungry locusts, which then mutate to gigantic size before drowning in Lake Michigan. Director Bert Gordon liked the concept so much he also helmed The Cyclops (1957), The Amazing Colossal Man (1957) and War of the Colossal Beast (1958), all of which also deal with the power of radiation.

In Fiend Without A Face (1958), a professor diverting power from a nuclear reactor for thought-materialization experiments inadvertently creates “mental vampires” that attach themselves to hapless victims. Eventually realizing the error of his ways, the scientist sacrifices himself helping the military blow the reactor up.

In The Alligator People (1959), a doctor treats accident victims with an alligator protein in the Louisiana bayou. However, the patients begin to exhibit gator features. A radical procedure to treat these gator-humans—cobalt 60 gamma rays and x-rays—is sabotaged, and the first test subject transforms into an alligator man before he sinks into a swamp.

In The Hideous Sun Demon (1959), a doctor is irradiated while working with a new isotope. As a consequence, sunlight causes him to devolve into a scaly prehistoric creature. As the transformations increase, so do the creature’s homicidal urges, but even when bludgeoning policemen, the creature has the decorum to wear dress pants before being shot.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

In Atom Age Vampire (1960), a professor must harvest cells from young women to replenish a serum that treats accident victims. Lacking the intestinal fortitude to carry out this task, he uses another serum to transform into a homicidal monster and then irradiates himself back to normal. When the transformation to monster becomes permanent, the scientist is killed by his mute assistant.

In The Beast of Yucca Flats (1961), a defecting Russian scientist is transformed into a crazed killer by a nuclear test before being shot.

And in Die, Monster, Die! (1965), Boris Karloff reprises his 1936 role in The Invisible Ray: a scientist whose experiments with meteor radiation are rooted in benevolence but end in death and self-destruction.

The modern era. Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) introduced audiences to the future of horror. However, not until 1968 would the radioactive bogeyman shamble, in black-and-white, into the modern era … in Pittsburgh. In George Romero’s landmark Night of the Living Dead, causation is never proven, but speculation centers on radiation from a destroyed satellite that is reactivating the brains of the dead. Thus: kill the brain, kill the ghoul. In Let Sleeping Corpses Lie (1974), images of pollution, overcrowding, and nuclear plant cooling towers grace the beginning of the film. “Ultrasonic radiation” is being used to destroy insects, but it also brings back the dead. Set in England and filmed in color, the movie draws from Romero yet achieves a creepiness all of its own.

In The Being (1983), the fictional Pottsville, Idaho is host to a waste disposal facility and a series of unexplained murders. A haughty scientist and government flack concludes that a young boy with damaged chromosomes was irradiated at the site, creating a creature that uses a higher percentage of its brain and is completely psychotic! In C.H.U.D. (1984), the homeless living underground are disappearing because radioactive and other waste is being dumped in the New York City sewers; the government’s Contamination Hazard Urban Disposal (C.H.U.D.) program is turning the vagrants into Cannibalistic Humanoid Underground Dwellers (C.H.U.D.s). Umberto Lenzi’s otherwise abysmal Nightmare City (1980) is notable in this context because the marauding mob is the product of a radioactive spill at a power plant.

In 2006, Alexandre Aja re-made, and slightly reinterpreted, Wes Craven’s 1977 tale of inter-familial savagery The Hills Have Eyes. The movie opens with a written admonition: “Between 1945 and 1962 the United States conducted 331 atmospheric nuclear tests. Today, the government still denies the genetic effects caused by the radioactive fallout …” Why the filmmakers chose 331 is unclear; 210 is the correct number. In Aja’s vision, before the US nuclear weapons testing program could begin, local residents were relocated. Some hid in the mines and it is their offspring that begin murdering a family on a cross-country trip. A grosser sequel was released in 2007.

Photo credit: IMDb

Meanwhile, the military was busy creating its own exotic weapons systems. In Piranha (1978), genetically modified and irradiated fish bred for use in Vietnam are unwittingly released upstream of a Texas community enjoying a summer day in the river; carnage ensues. A sequel of sorts, Piranha II: The Spawning (1981), was directed by debutant James Cameron but there is little evidence of the talent that would helm The Terminator three years later. In It’s Alive III: Island of the Alive (1987), the murderous mutant children of the first two movies are relocated to an island used for secret nuclear tests. A team of scientists predict a Darwinian up-side: “We see them as a jump in the evolutionary pattern; creatures capable of surviving a nuclear holocaust, withstanding radiation, even thriving on it.” In Spontaneous Combustion (1990), a shadowy corporation uses an anti-radiation drug to create a man with the ability to ignite people and be “the world’s most sophisticated nuclear weapon.”

There have also been several radioactive zombie comedies (Fido, 2006; Dance of the Dead, 2008) and some more (Mansquito, 2004) or less (Teeth, 2008) conventional creature features.

A decaying bogeyman? In November 1945, Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy reported the “locust-like effects” of the Red Army, a threat that manifested quite literally in Beginning of the End. As Peter Biskind notes in his 1983 book Seeing is Believing, the incredible mutations of the early Cold War movies most obviously represented communism: primitive aggressive hordes or emotionless repressive automatons depending on your political philosophy. Either way, in little more than an hour the monster was destroyed and normality restored; a victory for “us” over “them.”

With Romero and Roman Polanski’s infamous final Satan’s-child scene in Rosemary’s Baby setting the stage in 1968, modern era horror embraced the post-Vietnam/Watergate aesthetic, as the locus of the horror shifted from them to us. While plots are still largely driven by experiments gone awry, authorities are the conspirators, innocent people become the monsters, and nuclear power is just as dangerous as nuclear weapons—a conviction confirmed for some by the Three Mile Island accident in 1979. Creature features survive, but they are an increasingly small minority, and in a subtle but important change, the monsters are engineered rather than created by accident.

Of course very few of these movies are considered classics or even particularly good within the horror genre, let alone the broader cinematic oeuvre. Technical and budget limitations (attempts to obscure sound dubbing problems in The Beast of Yucca Flats need to be seen to be believed), borderline acting, and implausible plots means many don’t age well. But that doesn’t mean that they are unimportant. They reflect the anxieties of their eras and warn of the timeless dangers of scientific hubris.

It is worth noting that while the zombie, loosely defined, has made a comeback in the 2000s, biology has superseded radiation as the mutagen; see, for example, the Resident Evil franchise (2002-2016), 28 Days Later/28 Weeks Later (2002/2007), Planet Terror (2007), Zombieland and Carriers (2009), World War Z (2013) and Extinction (2015). However, one of the most significant findings of a 2005 UN study on the 1986 Chernobyl accident was that myths and misperceptions have resulted in “paralysing fatalism”—“negative self-assessments of health, belief in a shortened life expectancy, lack of initiative, and dependency on assistance from the state”—among residents in affected areas. While public understanding has improved, many of these fallacies and half-truths were reanimated with the Fukushima accident in 2011.

Although there are fewer nuclear weapons now than at the height of the Cold War, the risk of world-ending nuclear war remains. And regional instability, the proliferation of nuclear weapons and the materials to make them, and emerging global threats like cyber attacks and terrorism mean the risk of a single nuclear weapon or device being detonated—by accident, by miscalculation, or on purpose—is on the rise. While unlikely to enjoy a return to the halcyon B-movie years of the 1950s, the radioactive bogeyman likely has a long half-life.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Analysis, Nuclear Energy, Nuclear Weapons, Special Topics