The Doomsday Clock Through Time

The Clock Shifts

The Clock Shifts

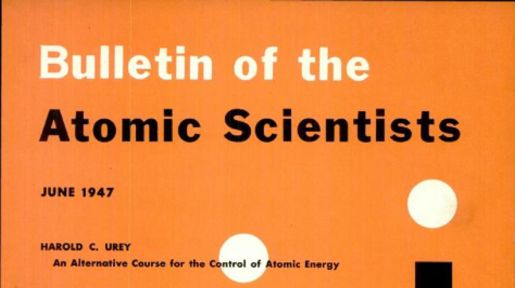

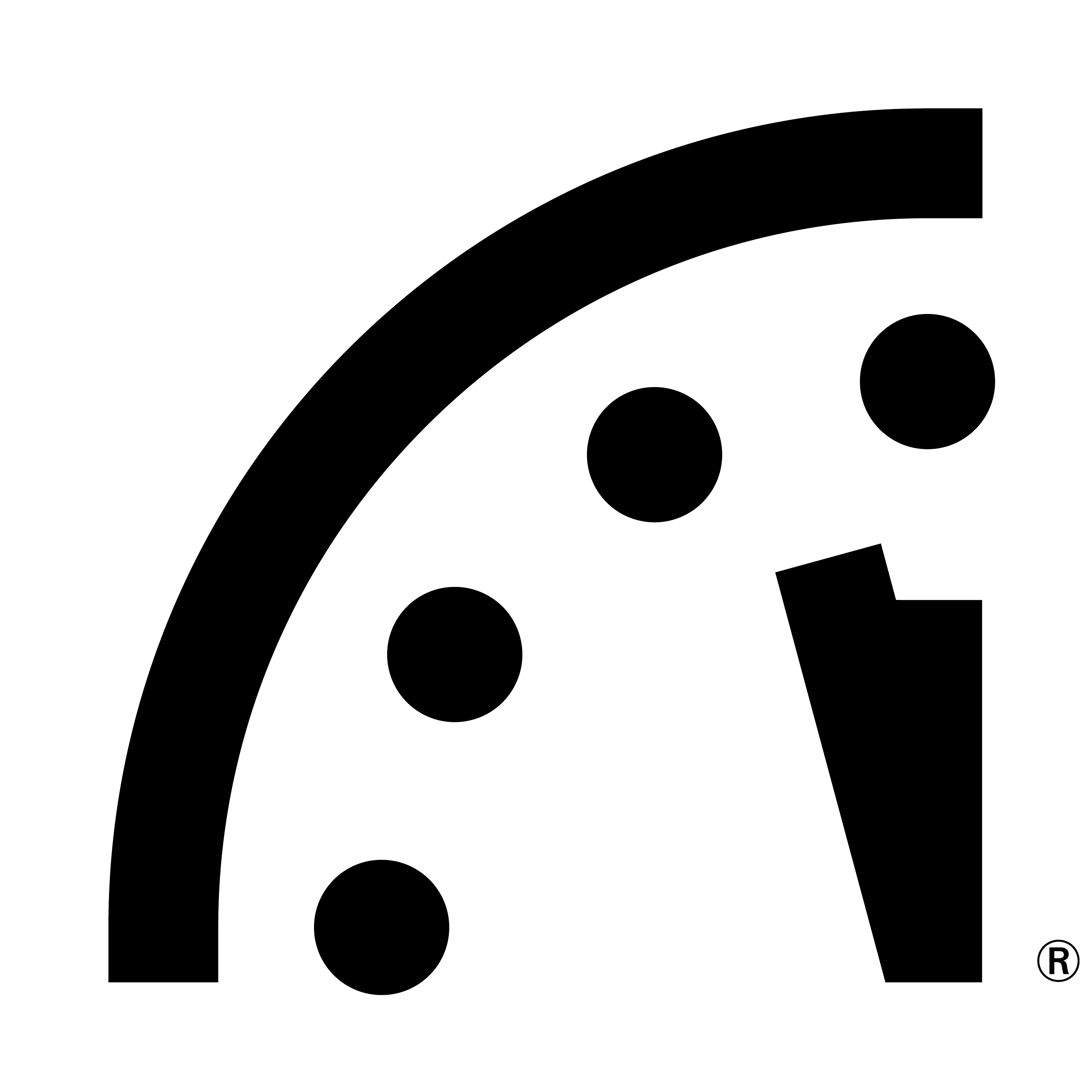

The Clock Starts Running

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists changes its format from a newsletter to a magazine. Its first cover features a clock, both conceptualized and designed by artist Martyl Langsdorf. At the time, Langsdorf designed it because “it seemed the right time on the page … it suited my eye.” This purely aesthetic design later becomes known as the “Doomsday Clock,” one of the most recognizable and lasting icons in popular culture to convey the urgency of nuclear danger. For decades to come, the Clock’s hands move based upon whether events push humanity closer to or further from nuclear apocalypse. The Clock later includes dangers posed by climate change and other existential threats.

The Arms Race is On

In the fall, at a remote site in Central Asia, the Soviet Union explodes a nuclear device—the design of which is very similar to that of the bomb that the United States used on Japan four years earlier. The Soviets deny the test, but US President Harry Truman shares the news with the American public about it, and the arms race begins. The Bulletin explains, “We do not advise Americans that doomsday is near and that they can expect atomic bombs to start falling on their heads a month or year from now. But we think they have reason to be deeply alarmed and to be prepared for grave decisions.”

The Horror of Hydrogen

Over the opposition of many nuclear scientists, the United States decides to pursue the hydrogen bomb, a weapon far more powerful than any atomic bomb. In October 1952, the United States tests its first thermonuclear device, obliterating a Pacific Ocean islet in the process. Nine months later, the Soviets test an H-bomb of their own. “The hands of the Clock of Doom have moved again, ” the Bulletin announces. “Only a few more swings of the pendulum, and, from Moscow to Chicago, atomic explosions will strike midnight for Western civilization.”

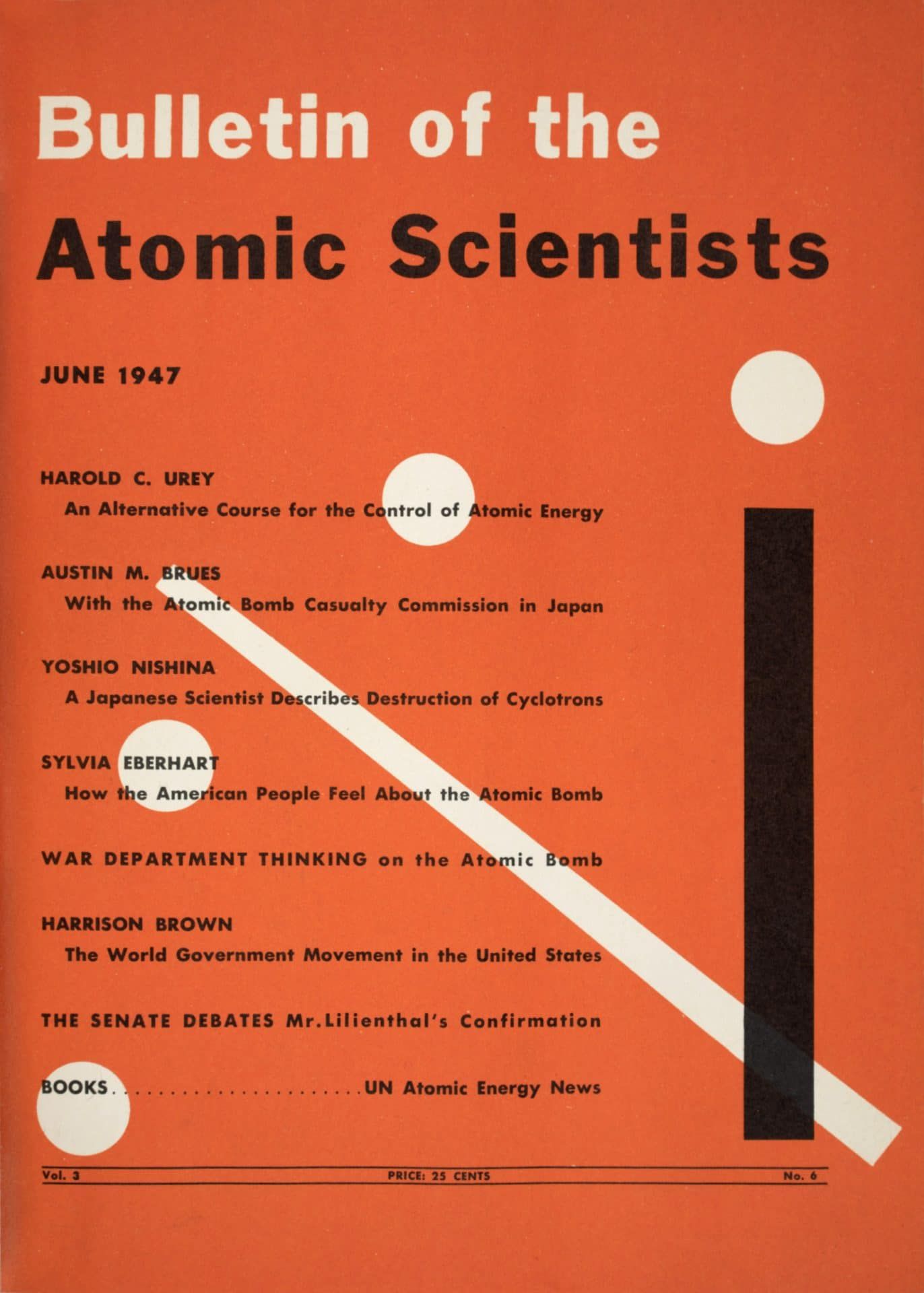

Cooperation, not Confrontation

Political actions belied the superpowers’ tough talk of “massive retaliation.” For the first time, the United States and the Soviet Union seek to avoid direct confrontation in regional conflicts such as the 1956 Egyptian-Israeli dispute. Joint projects to build trust and dialogue between third parties also help quell hostilities. Scientists initiate many of these measures: They help establish the International Geophysical Year, a series of coordinated, worldwide scientific events intended to raise public awareness, and the Pugwash Conferences, where Soviet and American scientists can interact.

A Rest from Tests

After the near-catastrophe of the Cuban Missile Crisis a year before and a decade of almost non-stop nuclear tests, the United States and the Soviet Union sign the Partial Test Ban Treaty, which ends all atmospheric nuclear testing. The treaty does nothing to outlaw underground testing, but it represents the first instance of concrete progress in at least slowing the arms race. It also signals awareness between the two countries that they must work together in order to prevent nuclear annihilation.

The Eastern World Explodes

While the superpowers wage the Cold War, much hotter wars rage in Asia. United States involvement in Vietnam intensifies, India and Pakistan battle over Kashmir in 1965, and Israel and its Arab neighbors renew hostilities in 1967. Worse yet, France and China develop nuclear weapons in order to assert themselves as global players. This combination of conventional warfare and nuclear proliferation causes the Bulletin’s editors to move the Clock’s minute hand toward midnight. The Bulletin recognizes the possibility that these regional conflicts could flare into wider wars with the potential use of nuclear weapons.

A Landmark Agreement

Nearly all of the world’s nations come together to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. The deal is simple: States with nuclear weapons vow to help the treaty’s other signatories develop nuclear power if they promise not to produce weapons. The nuclear weapon states also pledge to abolish their own arsenals when political conditions allow for it. Israel, India, and Pakistan refuse to sign, but the Bulletin remains cautiously optimistic: “The great powers have made the first step. They must proceed without delay to the next one—the dismantling, gradually, of their own oversized military establishments.”

Passing the SALT

After more than 20 years vying for arms, the United States and Soviet Union sign two treaties that attempt to curb the race for nuclear superiority in favor of rough parity between the superpowers. The Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT) limits the number of ballistic missile launchers either country can possess. The Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty seeks to stop a race for weapons designed to shoot down an adversary’s incoming nuclear missiles. SALT leaves the two countries with thousands of warheads pointed at each other, and the United States eventually withdraws from the ABM Treaty.

India Joins the Club

South Asia gets the bomb, as India tests its first nuclear device. Any gains in previous arms control agreements seem like a mirage. The United States and Soviet Union appear to be modernizing their nuclear forces, not reducing them. Thanks to the deployment of multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRV), both countries can now load their intercontinental ballistic missiles with more nuclear warheads than before.

Accelerating drift toward world disaster

As the Bulletin begins its 35th year, we feel impelled to record and to emphasize the accelerating drift toward world disaster in almost all realms of social activity. Alongside their failure to advance SALT treaty negotiations toward disarmament, both the United States and Soviet Union have been behaving like what may best be described as “nucleoholics.” Crises of resources, the spreading trend toward irrationality in the national and international conduct of many states and peoples, and the inability of international institutions to contain political crises move the hands of the clock forward.

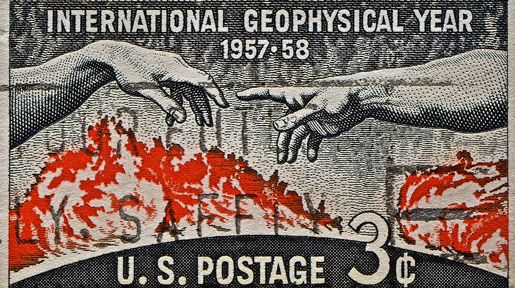

Reheating the Cold War

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and the 1980 election of Ronald Reagan in the United States both serve to harden the US nuclear posture. Before leaving office in January 1981, President Jimmy Carter pulls the United States from the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow and considers ways in which the United States can win, rather than avert, a nuclear war. Reagan intensifies the hawkish posturing by scrapping any talk of arms control and proposing that the best way to end the Cold War is for the United States to win.

Stalemate and Star Wars

As US-Soviet relations reach their iciest point in decades, dialogue between the two superpowers virtually stops. “Every channel of communication has been constricted or shut down; every form of contact has been attenuated or cut off. And arms control negotiations have been reduced to a species of propaganda, ” the Bulletin informs readers. The United States threatens to provoke a new arms race by seeking a space-based anti-ballistic missile system.

Protests Yield Progress

At the end of 1987, the United States and Soviet Union sign the historic Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, the first agreement to actually ban a whole category of nuclear weapons. The leadership shown by US President Ronald Reagan and Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev makes the treaty a reality, but Western European public opposition to US nuclear weapons inspired it. In the 1980s, both countries had increased the quantity and the deadliness of their intermediate-range missiles in Europe, keeping the continent in the crosshairs of the two superpowers.

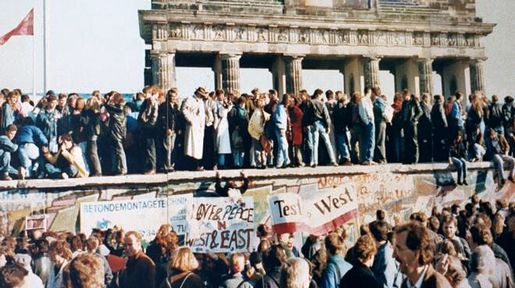

Lowering the Iron Curtain

The fall of the Berlin Wall in late 1989 symbolically ends the Cold War. Between 1989 and 1991, one Eastern European country after another overthrows its Soviet-backed government, while Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev repudiates his predecessors’ policies and refuses to intervene. These revolutions end the post-World War II ideological division of Europe and significantly diminish the risk of all-out nuclear war. “Forty-four years after Winston Churchill’s ‘Iron Curtain’ speech, the myth of monolithic communism has been shattered for all to see,” the Bulletin writes.

A Fresh START

With the Cold War officially over, the United States and Russia begin making deep cuts to their nuclear arsenals. US President George H.W. Bush and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev sign the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty. Known as START, the agreement greatly reduces the number of strategic nuclear weapons deployed by the two countries. Better still, a series of unilateral initiatives take most of the missiles and bombers in both countries off hair-trigger alert. The Bulletin declares: “The illusion that tens of thousands of nuclear weapons are a guarantor of national security has been stripped away.”

A Close Call

The year begins ominously when the Russian military mistakes a US-Norwegian scientific rocket for a nuclear missile and Russian President Boris Yeltsin must decide whether to launch a nuclear attack on the United States. That incident helps bolster the case made by US hard-liners that a resurgent Russia could be as much a threat as the Soviet Union. Hopes diminish for a large post-Cold War peace dividend, and more than 40,000 nuclear weapons remain worldwide. Concerns arise that terrorists could exploit poorly secured nuclear facilities within the former Soviet Union.

South Asia’s Nasty Surprise

Fourteen years after joining the ranks of countries with nuclear weapons, India carries out a series of nuclear tests that catch US intelligence off guard. The tests provoke worldwide outrage, and tensions heighten when Pakistan holds its own tests only three weeks later. The Bulletin calls the tests “a symptom of the failure of the international community to fully commit itself to control the spread of nuclear weapons.” Russia and the United States continue to serve as poor examples to the rest of the world, with a combined total of more than 7,000 weapons aimed at each other and ready to launch within 15 minutes.

New Worries, New Weapons

After the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the United States expresses increasing concerns about nuclear weapons falling into the hands of non-state actors. A top concern is the enormous amount of unsecured—and sometimes unaccounted for—weapon-grade nuclear materials throughout the world. The United States expresses a desire to design new nuclear weapons, especially ones that can destroy hardened and deeply buried targets. It also rejects a series of arms control treaties and announces that it will withdraw from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty that it had signed with the Soviet Union in 1972.

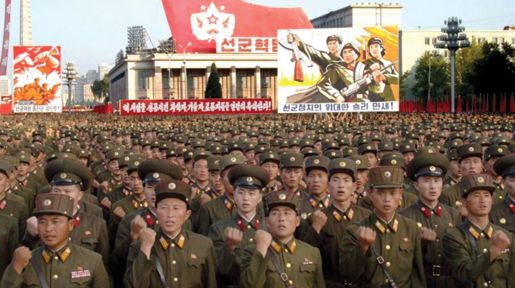

North Korea Rising

North Korea conducts a nuclear test, and many in the international community worry that Iran is working toward a bomb of its own. Meanwhile, the United States and Russia remain ready to wage nuclear war within minutes.

Hope after Copenhagen

Just before the start of the year, a breakthrough occurs at the United Nations climate change conference in Copenhagen. Both developing and industrialized countries agree to take responsibility for carbon emissions and to limit global temperature rise to 2 degrees Celsius. Washington and Moscow enter talks for a follow-on agreement to START and plan negotiations aimed at further cuts in the US and Russian nuclear arsenals. The Bulletin writes, “We are poised to bend the arc of history toward a world free of nuclear weapons.”

Desperately Seeking Solutions

Ridding the world of nuclear weapons, harnessing nuclear power, and managing the profound disruptions caused by climate change are complex and interconnected endeavors that the world's political processes have not fostered. The rhetoric of would-be nuclear provocateurs such as North Korea's Kim Jong-un underlines the potential for nuclear war in Northeast Asia; the nuclear situation in the Middle East and South Asia remains tense. Safer nuclear reactors with better oversight and training could help prevent power plant disasters, but technology-based approaches to managing climate change may not prevent widespread hardship.

Failures of Leadership

“Unchecked climate change, global nuclear weapons modernizations, and outsized nuclear weapons arsenals pose extraordinary and undeniable threats to the continued existence of humanity, and world leaders have failed to act with the speed or on the scale required to protect citizens from potential catastrophe. These failures of political leadership endanger every person on Earth.” Despite some modestly positive developments in the climate change arena, current efforts are entirely insufficient to prevent a catastrophic warming of Earth. Meanwhile, the United States and Russia have embarked on massive programs to modernize their nuclear triads-thereby undermining existing nuclear weapons treaties. “The clock ticks now at just three minutes to midnight because international leaders are failing to perform their most important duty—ensuring and preserving the health and vitality of human civilization.”

A half step toward Doomsday

“For the last two years, the minute hand of the Doomsday Clock stayed set at three minutes before the hour, the closest it had been to midnight since the early 1980s. In its two most recent annual announcements on the Clock, the Science and Security Board warned: ‘The probability of global catastrophe is very high, and the actions needed to reduce the risks of disaster must be taken very soon.’ In 2017, we find the danger to be even greater, the need for action more urgent. It is two and a half minutes to midnight, the Clock is ticking, global danger looms. Wise public officials should act immediately, guiding humanity away from the brink. If they do not, wise citizens must step forward and lead the way.”

2 Minutes to Midnight

“The warning the Science and Security Board now sends is clear, the danger obvious and imminent. The opportunity to reduce the danger is equally clear. The world has seen the threat posed by the misuse of information technology and witnessed the vulnerability of democracies to disinformation. But there is a flip side to the abuse of social media. Leaders react when citizens insist they do so, and citizens around the world can use the power of the internet to improve the long-term prospects of their children and grandchildren. They can insist on facts, and discount nonsense. They can demand action to reduce the existential threat of nuclear war and unchecked climate change. They can seize the opportunity to make a safer and saner world.”

100 Seconds to Midnight

Humanity continues to face two simultaneous existential dangers—nuclear war and climate change—that are compounded by a threat multiplier, cyber-enabled information warfare, that undercuts society’s ability to respond. Faced with this daunting threat landscape and a new willingness of political leaders to reject the negotiations and institutions that can protect civilization over the long term, the Science and Security Board moved the Doomsday Clock 20 seconds closer to midnight—a warning to leaders and citizens around the world that the international security situation is now more dangerous than it has ever been, even at the height of the Cold War.

90 Seconds to Midnight

The Science and Security Board moves the hands of the Doomsday Clock forward, largely (though not exclusively) because of the mounting dangers of the war in Ukraine. The war has raised profound questions about how states interact, eroding norms of international conduct that underpin successful responses to a variety of global risks. The Clock now stands at 90 seconds to midnight—the closest to global catastrophe it has ever been.

89 Seconds to Midnight

In 2024, humanity edged ever closer to catastrophe. Despite unmistakable signs of danger, national leaders and their societies have failed to do what is needed to change course. In setting the Clock one second closer to midnight, the Science and Security Board sends a stark signal: Because the world is already perilously close to the precipice, a move of even a single second should be taken as an indication of extreme danger and an unmistakable warning that every second of delay in reversing course increases the probability of global disaster.

Culture & The Clock

Culture & The Clock

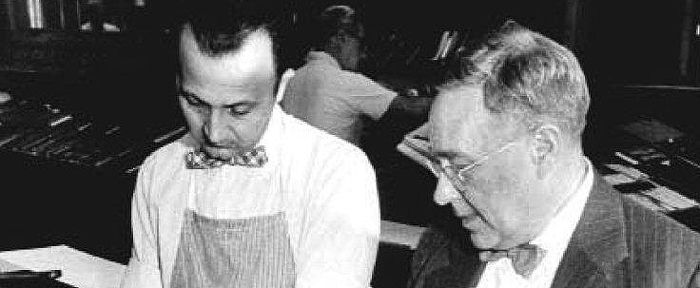

Moving the Minute Hand

The Doomsday Clock’s minute hand moves for the first time upon news of the Soviet atomic bomb test. Bulletin editor Eugene Rabinowitch, a leading scientist in the movement for international control of atomic energy, consults his colleagues before changing the minute hand on the cover design from 7 minutes to midnight to 3 minutes to midnight. Known for his broad and active network of independent scientists and his ability to capture the prevailing wisdom about world politics and the nuclear arms race, Rabinowitch is responsible for every movement of the minute hand until his death in 1973.

Doomsday and Dissent

After the Cuban Missile Crisis and before the escalation of the United States’ role in Vietnam, US public opinion broadly supports the Cold War and the country's nuclear policies. Against this backdrop, satire is an effective tool for questioning the conventional wisdom about nuclear weapons. Stanley Kubrick’s film, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, uses the darkest of black comedy, a remarkable three-role performance by Peter Sellers, and the specter of a Soviet “doomsday device” to take issue with the arms race between the superpowers.

The End of an Era

Eugene Rabinowitch dies, and the Bulletin’s board of directors assumes the responsibility for setting the Doomsday Clock. Before making decisions, the directors consult scientific and other expert colleagues, especially the distinguished members of the Bulletin’s Board of Sponsors.

The Clock in Fiction

American mystery writer Helen McCloy (also known as Helen Clarkson) publishes her novel The Impostor. She employs the Doomsday Clock as a plot device in the story of a woman named Marina who recovers consciousness after a car crash to find herself in a psychiatric clinic and who becomes a pawn in someone else's sinister game.

The Nuclear Culture

Thirty-five years into the nuclear era, cultural references to the Doomsday Clock and nuclear peril abound. The Clash releases Sandinista, a triple album that includes “The Call Up,” a song that references the Doomsday Clock with the line “It’s 55 minutes past 11.” Meanwhile in the political sphere, the superpowers cling to nuclear weapons, to the Bulletin’s dismay: “The Soviet Union and United States have been behaving like what may best be described as ‘nucleoholics’—drunks who continue to insist that the drink being consumed is positively ‘the last one’ but who can always find a good excuse for ‘just one more round.’”

Doctor Who ...

Doomsday motifs continue to proliferate in popular culture as evidenced by the title of an episode of the BBC science fiction television program Dr. Who: “Four to Doomsday.”

... and The Who Too

The Who's album “It's Hard” taps into early 1980s nuclear anxiety. The song “Why Did I Fall for That?” mentions the Doomsday Clock specifically: “Four minutes to midnight on a sunny day maybe if we smile the clock'll fade away maybe we can force the hands to just reverse.” Another song, “I've Known No War,” also expresses the fears and hopes for peace of those who came of age during the Cold War decades. Meanwhile the board game Trivial Pursuit becomes a cultural phenomenon. Later editions include this question: “What clock was created to adorn The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists?”

Two Minutes … and 30 Years

British heavy metal band Iron Maiden releases the song “Two Minutes to Midnight.” It rises to number 11 on the UK singles chart. Contrary to popular belief it doesn't mention either 1980s Cold War tensions or the Cuban Missile Crisis but was instead inspired by hydrogen bomb tests in the 1950s.

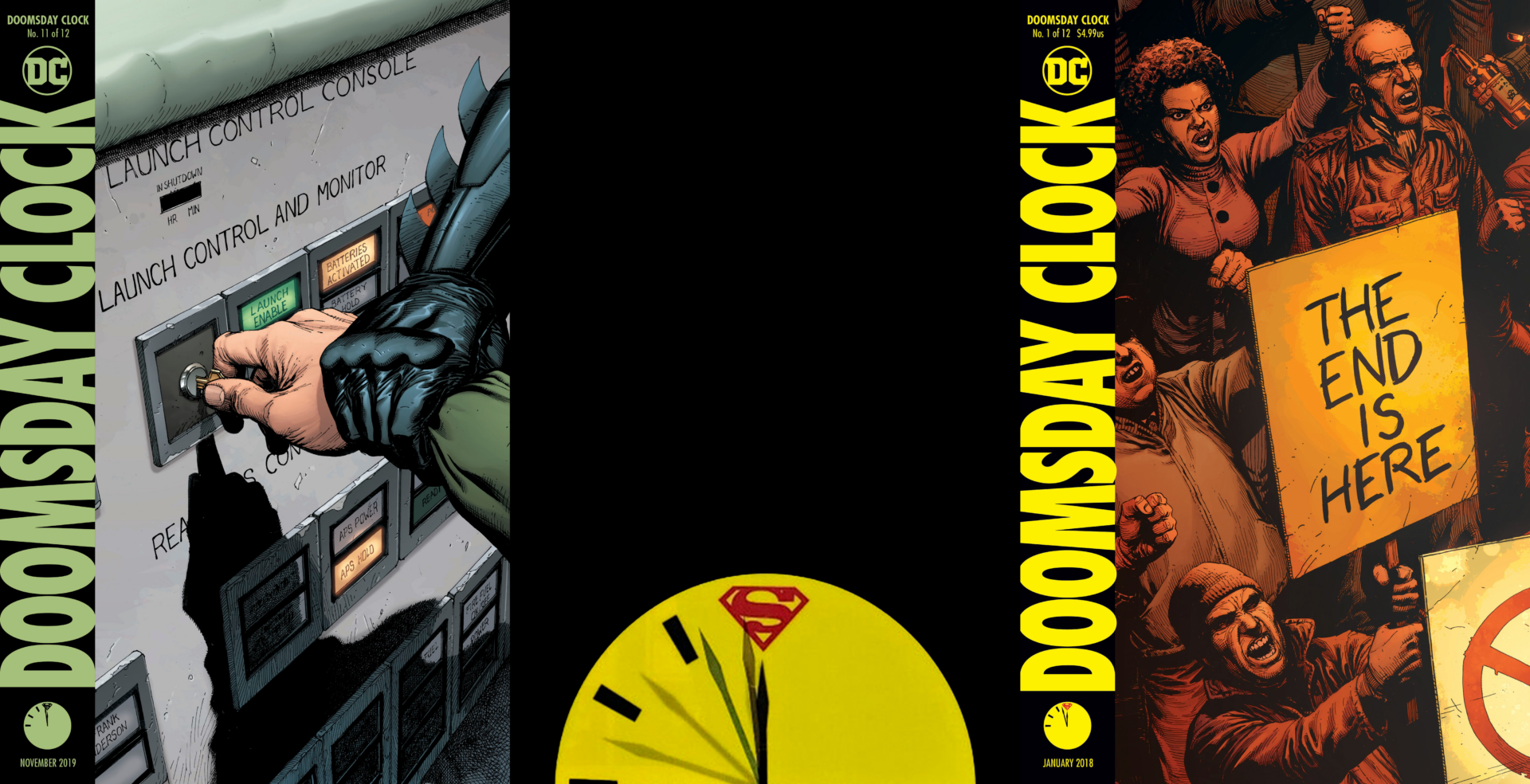

Watching the Clock

Alan Moore publishes his graphic novel Watchmen in which the Doomsday Clock is an ominous recurring presence. It takes place in an alternate version of 1985 in which the United States and the Soviet Union are preparing for an impending nuclear war.

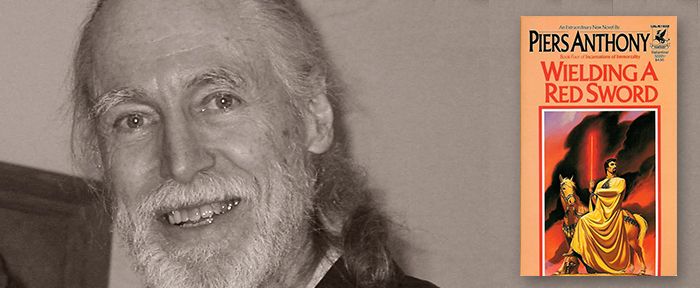

Bringing Fear to Fantasy

Bestselling science fiction and fantasy writer Piers Anthony publishes his novel, Wielding a Red Sword. In the book, a character known as The Incarnation of War can use the Doomsday Clock to bring about World War III.

Off-the-Charts Exuberance

The Bulletin’s board of directors vigorously debates how far back from midnight the Doomsday Clock’s hands should be moved now that the Soviet Union has broken apart and the Cold War has ended. The time they choose—17 minutes to midnight—requires the minute hand to be moved to a position outside the portion of the Clock depicted on the original design. The change symbolizes the euphoria many feel for surviving 45 years without a nuclear exchange between the United States and the Soviet Union.

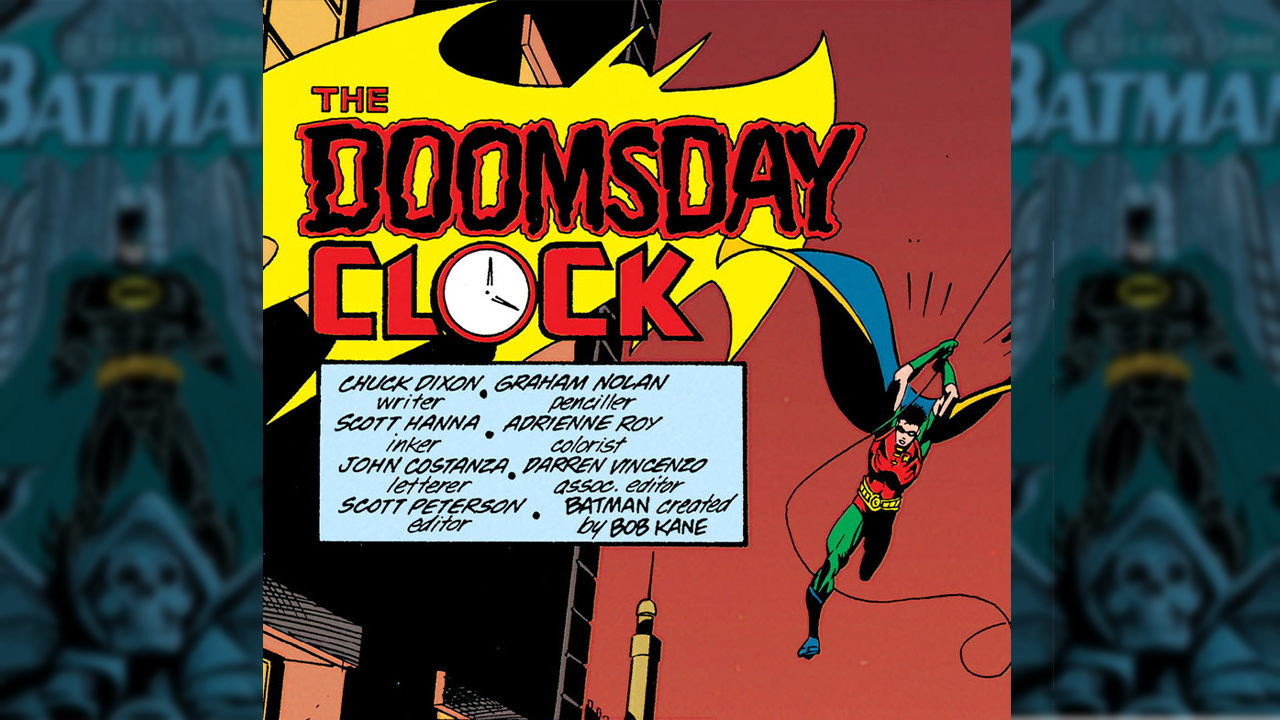

Holy clock hands, Batman!

DC Comics writer Chuck Dixon titled Detective Comics #635 "The Doomsday Clock." In this issue, Bruce Wayne tries to regain his hold on Wayne Enterprises and his role as Batman after an injury. At the climax of the story, the big baddie—Soviet master assassin KGBeast—threatens to blow up Gotham City with a baseball-size nuclear bomb.

A Deadly Serious Game

Microsoft publishes the online game Rise of Nations which features a Doomsday Clock-like “Armageddon timer.” Each time a player fires a nuclear missile the timer counts down by one tick—when the timer reaches zero a nuclear holocaust engulfs the Earth and all players lose.

Bright Eyes Dark Thoughts

Bright Eyes releases the song “Easy/Lucky/Free.” It includes the lines “I set my watch to the atomic clock I hear the crowd count down 'til the bomb gets dropped I always figured that there’d be time enough I never let it get me down.”

Not Just Nukes

The Bulletin’s board determines that the Doomsday Clock should also take existential threats outside nuclear catastrophe into account, specifically the Earth-threatening dangers posed by climate change and rapid developments in the life sciences and other emerging technologies. Against this backdrop, the US band Smashing Pumpkins releases its song “Doomsday Clock,” which later appears in professional wrestling, monster truck competitions, and a trailer for the film The Incredible Hulk.

Still Watching the Clock

Nearly 20 years after the end of the Cold War, the Doomsday Clock remains a potent symbol of civilization’s vulnerability and the anxiety of life in a world full of nuclear weapons. In director Zack Snyder’s film adaptation of Alan Moore’s Watchmen, the clock remains an ominous recurring presence, even though the film changes many of the novel’s other details and plot points.

Remembering Martyl

Martyl Langsdorf, the creator of the Doomsday Clock, dies on March 26 at the age of 96. Her work appeared in exhibitions at a variety of leading institutions, including the Art Institute of Chicago, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the St. Louis Art Museum. Her landscapes and still lifes are in the permanent collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington DC. Her last cover design for the Bulletin was for the May/June 2007 issue.

A Primetime Spot

The second season of the hit CBS show Madam Secretary includes the Doomsday Clock in a fantastical subplot: To protect the US president’s election chances, Secretary of State Elizabeth McCord is tasked with persuading the Bulletin not to move the Clock hands forward as planned. When the lobbying effort doesn't go as hoped, McCord’s chief of staff says, "You can’t dissuade people with that much integrity. They’re in the pocket of Big Truth..."

The Doomsday Clock and the Justice League

Between 2017 and 2019, DC Comics publishes 12 issues of a comic-book series titled Doomsday Clock. Written by Geoff Johns, the series brings back Watchmen characters like Doctor Manhattan and puts them in the same pages as Superman and Batman. The second issue in the series depicts scientists announcing the Doomsday Clock hands have moved to 3 minutes to midnight. At the time it’s published, the real Clock actually was set to two and a half minutes. If that was not proof enough that this comic is fully fictional, the white lab coats worn by the comic-book Bulletin representatives should be.

Watching the Watchmen, on TV

Damon Lindelof, a creator of the hit series Lost, brings Alan Moore's Watchmen universe to TV in a new limited HBO series he describes as a remix of the original story, not a reboot. “The Old Testament was specific to the Eighties of Reagan and Thatcher and Gorbachev,” Lindelof tells fans. “Ours needs to resonate with the frequency of Trump and May and Putin.” Regina King stars in the series, which garners critical acclaim and goes on to win 11 Emmy awards.

Clock Settings & Statements

Clock Statements

2025

IT IS 89 SECONDS TO MIDNIGHT

2024

IT IS STILL 90 SECONDS TO MIDNIGHT

2023

IT IS 90 SECONDS TO MIDNIGHT

2022

IT IS STILL 100 SECONDS TO MIDNIGHT

Leaders around the world must immediately commit 2022 themselves to renewed cooperation in the many ways and venues available for reducing existential risk. Citizens of the world can and should organize to demand that their leaders do so—and quickly. The doorstep of doom is no place to loiter.

2021

IT IS STILL 100 SECONDS TO MIDNIGHT

If humanity is to avoid an existential catastrophe—one that would dwarf anything it has yet seen—national leaders must do a far better job of countering disinformation, heeding science, and cooperating to diminish global risks. Citizens around the world can and should organize and demand—through public protests, at ballot boxes, and in other creative ways—that their governments reorder their priorities and cooperate domestically and internationally to reduce the risk of nuclear war, climate change, and other global disasters, including pandemic disease.

2020

IT IS 100 SECONDS TO MIDNIGHT

Civilization-ending nuclear war—whether started by design, blunder, or simple miscommunication—is a genuine possibility. Climate change that could devastate the planet is undeniably happening. And for a variety of reasons that include a corrupted and manipulated media environment, democratic governments and other institutions that should be working to address these threats have failed to rise to the challenge. Faced with a daunting threat landscape and a new willingness of political leaders to reject the negotiations and institutions that can protect civilization over the long term, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Science and Security Board moved the Doomsday Clock 20 seconds closer to midnight—closer to apocalypse than ever. See the full statement from the Science and Security Board on the 2020 time of the Doomsday Clock.

2019

IT IS STILL 2 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

As the Bulletin’s Science and Security Board prepared for its first set of Doomsday Clock discussions this fall, it began referring to the current world security situation as a “new abnormal.” This new abnormal is a pernicious and dangerous departure from the time when the United States sought a leadership role in designing and supporting global agreements that advanced a safer and healthier planet. The new abnormal describes a moment in which fact is becoming indistinguishable from fiction, undermining our very abilities to develop and apply solutions to the big problems of our time. The new abnormal risks emboldening autocrats and lulling citizens around the world into a dangerous sense of anomie and political paralysis.See the full statement from the Science and Security Board on the 2019 time of the Doomsday Clock.

2018

IT IS 2 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

The failure of world leaders to address the largest threats to humanity’s future is lamentable—but that failure can be reversed. It is two minutes to midnight, but the Doomsday Clock has ticked away from midnight in the past, and during the next year, the world can again move it further from apocalypse. The warning the Science and Security Board now sends is clear, the danger obvious and imminent. The opportunity to reduce the danger is equally clear. The world has seen the threat posed by the misuse of information technology and witnessed the vulnerability of democracies to disinformation. But there is a flip side to the abuse of social media. Leaders react when citizens insist they do so, and citizens around the world can use the power of the internet to improve the long-term prospects of their children and grandchildren. They can insist on facts, and discount nonsense. They can demand action to reduce the existential threat of nuclear war and unchecked climate change. They can seize the opportunity to make a safer and saner world. See the full statement from the Science and Security Board on the 2018 time of the Doomsday Clock.

2017

IT IS 2 AND A HALF MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

For the last two years, the minute hand of the Doomsday Clock stayed set at three minutes before the hour, the closest it had been to midnight since the early 1980s. In its two most recent annual announcements on the Clock, the Science and Security Board warned: “The probability of global catastrophe is very high, and the actions needed to reduce the risks of disaster must be taken very soon.” In 2017, we find the danger to be even greater, the need for action more urgent. It is two and a half minutes to midnight, the Clock is ticking, global danger looms. Wise public officials should act immediately, guiding humanity away from the brink. If they do not, wise citizens must step forward and lead the way. See the full statement from the Science and Security Board on the 2017 time of the Doomsday Clock.

2016

IT IS STILL 3 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

"Last year, the Science and Security Board moved the Doomsday Clock forward to three minutes to midnight, noting: 'The probability of global catastrophe is very high, and the actions needed to reduce the risks of disaster must be taken very soon.' That probability has not been reduced. The Clock ticks. Global danger looms. Wise leaders should act—immediately." See the full statement from the Science and Security Board on the 2016 time of the Doomsday Clock.

2015

IT IS 3 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

"Unchecked climate change, global nuclear weapons modernizations, and outsized nuclear weapons arsenals pose extraordinary and undeniable threats to the continued existence of humanity, and world leaders have failed to act with the speed or on the scale required to protect citizens from potential catastrophe. These failures of political leadership endanger every person on Earth." Despite some modestly positive developments in the climate change arena, current efforts are entirely insufficient to prevent a catastrophic warming of Earth. Meanwhile, the United States and Russia have embarked on massive programs to modernize their nuclear triads-thereby undermining existing nuclear weapons treaties. "The clock ticks now at just three minutes to midnight because international leaders are failing to perform their most important duty—ensuring and preserving the health and vitality of human civilization." Read the full statement.

2012

IT IS 5 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

"The challenges to rid the world of nuclear weapons, harness nuclear power, and meet the nearly inexorable climate disruptions from global warming are complex and interconnected. In the face of such complex problems, it is difficult to see where the capacity lies to address these challenges." Political processes seem wholly inadequate; the potential for nuclear weapons use in regional conflicts in the Middle East, Northeast Asia, and South Asia are alarming; safer nuclear reactor designs need to be developed and built, and more stringent oversight, training, and attention are needed to prevent future disasters; the pace of technological solutions to address climate change may not be adequate to meet the hardships that large-scale disruption of the climate portends. Read the full statement.

2010

IT IS 6 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

"We are poised to bend the arc of history toward a world free of nuclear weapons" is the Bulletin's assessment. Talks between Washington and Moscow for a follow-on agreement to the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty are nearly complete, and more negotiations for further reductions in the U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenal are already planned. The dangers posed by climate change are growing, but there are pockets of progress. Most notably, at Copenhagen, the developing and industrialized countries agree to take responsibility for carbon emissions and to limit global temperature rise to 2 degrees Celsius. Read the full statement.

2007

IT IS 5 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

The world stands at the brink of a second nuclear age. The United States and Russia remain ready to stage a nuclear attack within minutes, North Korea conducts a nuclear test, and many in the international community worry that Iran plans to acquire the Bomb. Climate change also presents a dire challenge to humanity. Damage to ecosystems is already taking place; flooding, destructive storms, increased drought, and polar ice melt are causing loss of life and property. Read the full statement.

2002

IT IS 7 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

Concerns regarding a nuclear terrorist attack underscore the enormous amount of unsecured — and sometimes unaccounted for — weapon-grade nuclear materials located throughout the world. Meanwhile, the United States expresses a desire to design new nuclear weapons, with an emphasis on those able to destroy hardened and deeply buried targets. It also rejects a series of arms control treaties and announces it will withdraw from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. Read the full statement.

1998

IT IS 9 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

India and Pakistan stage nuclear weapons tests only three weeks apart. "The tests are a symptom of the failure of the international community to fully commit itself to control the spread of nuclear weapons — and to work toward substantial reductions in the numbers of these weapons," a dismayed Bulletin reports. Russia and the United States continue to serve as poor examples to the rest of the world. Together, they still maintain 7,000 warheads ready to fire at each other within 15 minutes. Read the full statement.

1995

IT IS 14 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

Hopes for a large post-Cold War peace dividend and a renouncing of nuclear weapons fade. Particularly in the United States, hard-liners seem reluctant to soften their rhetoric or actions, as they claim that a resurgent Russia could provide as much of a threat as the Soviet Union. Such talk slows the rollback in global nuclear forces; more than 40,000 nuclear weapons remain worldwide. There is also concern that terrorists could exploit poorly secured nuclear facilities in the former Soviet Union. Read the full statement.

1991

IT IS 17 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

With the Cold War officially over, the United States and Russia begin making deep cuts to their nuclear arsenals. The Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty greatly reduces the number of strategic nuclear weapons deployed by the two former adversaries. Better still, a series of unilateral initiatives remove most of the intercontinental ballistic missiles and bombers in both countries from hair-trigger alert. "The illusion that tens of thousands of nuclear weapons are a guarantor of national security has been stripped away," the Bulletin declares. Read the full statement.

1990

IT IS 10 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

"We are poised to bend the arc of history toward a world free of nuclear weapons" is the Bulletin's assessment. Talks between Washington and Moscow for a follow-on agreement to the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty are nearly complete, and more negotiations for further reductions in the U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenal are already planned. The dangers posed by climate change are growing, but there are pockets of progress. Most notably, at Copenhagen, the developing and industrialized countries agree to take responsibility for carbon emissions and to limit global temperature rise to 2 degrees Celsius. Read the full statement.

1988

IT IS 6 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

The United States and Soviet Union sign the historic Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, the first agreement to actually ban a whole category of nuclear weapons. The leadership shown by President Ronald Reagan and Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev makes the treaty a reality, but public opposition to U.S. nuclear weapons in Western Europe inspires it. For years, such intermediate-range missiles had kept Western Europe in the crosshairs of the two superpowers. Read the full statement.

1984

IT IS 3 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

U.S.-Soviet relations reach their iciest point in decades. Dialogue between the two superpowers virtually stops. "Every channel of communications has been constricted or shut down; every form of contact has been attenuated or cut off. And arms control negotiations have been reduced to a species of propaganda," a concerned Bulletin informs readers. The United States seems to flout the few arms control agreements in place by seeking an expansive, space-based anti-ballistic missile capability, raising worries that a new arms race will begin. Read the full statement.

1981

IT IS 4 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan hardens the U.S. nuclear posture. Before he leaves office, President Jimmy Carter pulls the United States from the Olympic Games in Moscow and considers ways in which the United States could win a nuclear war. The rhetoric only intensifies with the election of Ronald Reagan as president. Reagan scraps any talk of arms control and proposes that the best way to end the Cold War is for the United States to win it. Read the full statement.

1980

IT IS 7 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

Thirty-five years after the start of the nuclear age and after some promising disarmament gains, the United States and the Soviet Union still view nuclear weapons as an integral component of their national security. This stalled progress discourages the Bulletin: "[The Soviet Union and United States have] been behaving like what may best be described as 'nucleoholics' — drunks who continue to insist that the drink being consumed is positively 'the last one,' but who can always find a good excuse for 'just one more round.'" Read the full statement.

1974

IT IS 9 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

South Asia gets the Bomb, as India tests its first nuclear device. And any gains in previous arms control agreements seem like a mirage. The United States and Soviet Union appear to be modernizing their nuclear forces, not reducing them. Thanks to the deployment of multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRV), both countries can now load their intercontinental ballistic missiles with more nuclear warheads than before. Read the full statement.

1972

IT IS 12 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

The United States and Soviet Union attempt to curb the race for nuclear superiority by signing the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT) and the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty. The two treaties force a nuclear parity of sorts. SALT limits the number of ballistic missile launchers either country can possess, and the ABM Treaty stops an arms race in defensive weaponry from developing. Read the full statement.

1969

IT IS 10 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

Nearly all of the world's nations come together to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. The deal is simple — the nuclear weapon states vow to help the treaty's non-nuclear weapon signatories develop nuclear power if they promise to forego producing nuclear weapons. The nuclear weapon states also pledge to abolish their own arsenals when political conditions allow for it. Although Israel, India, and Pakistan refuse to sign the treaty, the Bulletin is cautiously optimistic: "The great powers have made the first step. They must proceed without delay to the next one — the dismantling, gradually, of their own oversized military establishments." Read the full statement.

1968

IT IS 7 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

Regional wars rage. U.S. involvement in Vietnam intensifies, India and Pakistan battle in 1965, and Israel and its Arab neighbors renew hostilities in 1967. Worse yet, France and China develop nuclear weapons to assert themselves as global players. "There is little reason to feel sanguine about the future of our society on the world scale," the Bulletin laments. "There is a mass revulsion against war, yes; but no sign of conscious intellectual leadership in a rebellion against the deadly heritage of international anarchy." Read the full statement.

1963

IT IS 12 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

After a decade of almost non-stop nuclear tests, the United States and Soviet Union sign the Partial Test Ban Treaty, which ends all atmospheric nuclear testing. While it does not outlaw underground testing, the treaty represents progress in at least slowing the arms race. It also signals awareness among the Soviets and United States that they need to work together to prevent nuclear annihilation. Read the full statement.

1960

IT IS 7 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

Political actions belie the tough talk of "massive retaliation." For the first time, the United States and Soviet Union appear eager to avoid direct confrontation in regional conflicts such as the 1956 Egyptian-Israeli dispute. Joint projects that build trust and constructive dialogue between third parties also quell diplomatic hostilities. Scientists initiate many of these measures, helping establish the International Geophysical Year, a series of coordinated, worldwide scientific observations, and the Pugwash Conferences, which allow Soviet and American scientists to interact. Read the full statement.

1953

IT IS 2 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

After much debate, the United States decides to pursue the hydrogen bomb, a weapon far more powerful than any atomic bomb. In October 1952, the United States tests its first thermonuclear device, obliterating a Pacific Ocean islet in the process; nine months later, the Soviets test an H-bomb of their own. "The hands of the Clock of Doom have moved again," the Bulletin announces. "Only a few more swings of the pendulum, and, from Moscow to Chicago, atomic explosions will strike midnight for Western civilization." Read the full statement.

1949

IT IS 3 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

The Soviet Union denies it, but in the fall, President Harry Truman tells the American public that the Soviets tested their first nuclear device, officially starting the arms race. "We do not advise Americans that doomsday is near and that they can expect atomic bombs to start falling on their heads a month or year from now," the Bulletin explains. "But we think they have reason to be deeply alarmed and to be prepared for grave decisions." Read the full statement.

1947

IT IS 7 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT

As the Bulletin evolves from a newsletter into a magazine, the Clock appears on the cover for the first time. It symbolizes the urgency of the nuclear dangers that the magazine's founders — and the broader scientific community — are trying to convey to the public and political leaders around the world. Read about Martyl Langsdorf, the creator of the Doomsday Clock, and read her note about how and why she came up with the design for what graphic designer Michael Beirut calls "the most powerful piece of information design of the 20th Century."