What could happen if a Democratic president declared a national climate emergency

By Jackie Flynn Mogensen | March 9, 2019

Credit: Mother Jones illustration

Credit: Mother Jones illustration

Editor’s note: This story was originally published by Mother Jones. It appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Over and over, President Donald Trump has done things no sitting president would dare do. In February, the country again entered new terrain when he declared a national emergency, effectively unlocking billions of dollars in emergency funding for his border wall. Almost immediately, members of both parties started theorizing—and sounding the alarm—about the precedent such a move would set.

On one side, Democrats like House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) were quick to argue that the declaration was a bad move—but suggested that a future Democratic president could use the same powers for a different emergency, like climate change or gun control. After all, the two issues, they argued, have far more legitimacy as emergencies than Trump’s “border crisis.”

This line of thinking has sent Republicans like Sens. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Thom Tillis (R-N.C.) into something of a panic. As Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) warned in an interview with CNBC in January: “If today the national emergency is border security… tomorrow the national emergency might be climate change.”

Now, with the support of Tillis and Sens. Susan Collins (R-Maine), Lisa Murkowski (R-Ala.), and Rand Paul (R-Ky.), there seem to be enough votes in the Senate to pass a resolution to stop Trump’s emergency, which already passed the House. But, as neither chamber is likely to have enough votes to override Trump’s almost-certain veto, its fate will almost assuredly be left up to the courts, following an onslaught of lawsuits.

But we’ve been wondering: What would a national emergency declaration over climate change really look like, hypothetically speaking? And, crucially, is it even a good idea?

“Declaring an emergency isn’t a magic wand,” says Dan Farber, a law professor and faculty director of the Center for Law, Energy, and the Environment at the University of California-Berkeley. “What declaring an emergency does is allow the president or administrative agencies to then take advantage of a long list of statutes that have national emergency triggers,” as permitted by the National Emergencies Act of 1976. While doing so, he says, is “not an excuse for the president to take over the country,” it could do some good.

“This is something even a moderate Democrat really ought to think about,” Farber argues.

To be clear, the feasibility of a climate emergency largely depends on if the courts uphold Trump’s emergency declaration (and, of course, a future president’s willingness to declare one). As Andrew Boyle, counsel in the Liberty and National Security Program at the Brennan Center, a nonpartisan law and policy institute out of New York University, points out, there is no real definition of what constitutes an “emergency” in the eyes of the law.

“This is the first time a president has used emergency powers under the National Emergencies Act after asking Congress and not being able to do it,” he says. “So in a lot of ways, we’re in sort of uncharted territory, and we’ll have to wait and see what happens in the courts.”

Caveats aside, here are five key actions a president could take to address climate change under a declaration of national emergency:

1. Divert military money to fund renewable energy and climate-related construction projects. If this sounds familiar, that’s because it’s basically what Trump plans to do for his wall. In his emergency declaration, Trump invoked statute 10 USC 2808 to unlock “up to $3.6 billion” of Pentagon funds for wall construction, according to the White House. Importantly, statute 2808 only authorizes the president to redistribute military funding for construction projects that support the military. It’s unclear if Trump’s argument that the wall supports the military will withstand legal muster, but if the courts give it the go-ahead, it’s possible that the same statute could also be applied to fund green energy construction projects, according to Boyle—assuming the federal government could successfully argue that fighting climate change is supporting the military.

In a January story for Legal Planet, a law blog run by the University of California-Los Angeles and Berkeley, Farber writes that those projects could include building wind or solar farms or new transmission lines for renewable power sources. Depending on what standard the court sets, “anything that increases reliability to the grid could be supporting the military,” he says.

There’s also another possible interpretation of statute 2808, according to Mark Nevitt, a former environmental attorney in the Navy Judge Advocate General’s Corps who served as the Defense Department’s regional environmental counsel in Norfolk, Virginia: to use funds to protect vulnerable military bases from rising sea levels, violent storms, or other climate-related threats. (The amount of money available for these sorts of projects depends on how much has already been allocated for military construction.)

The case for renovating military bases could be supported by a January 2019 Pentagon report focused on 79 “priority” armed-forces installations across military branches. It showed that 53 installations currently see recurrent flooding, 43 experience drought, 36 are threatened by wildfires, six face desertification, and one is confronting thawing permafrost. And those are just the installations that are currently encountering climate threats; an even greater number of installations will be vulnerable in the next 20 years, the report found.

2. Block domestic oil drilling. Farber’s blog post makes the point bluntly: “If climate change is a national emergency caused by fossil fuels, then suspension [of oil leases] seems like a logical response.” In an interview, he adds, “Federal oil leases have a clause allowing them to be suspended during national emergencies. So, one pretty dramatic possibility would be to go suspend a lot of oil leases, which obviously would create a huge uproar—but that might or might not be a good thing.”

This could, in theory, apply to more than 38,000 oil and gas leases on federal land (the amount in the 2017 fiscal year, the most recent data available from the Interior Department). So suspending oil leases could have a major impact on emissions; according to a 2018 report by the Trump administration, drilling on public lands contributes nearly a quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions in the United States.

3. Restrict car emissions. Statute 49 USC 114, which grants the Transportation Security Administration administrator the ability to “coordinate domestic transportation” during a national emergency, could possibly be interpreted to place restrictions on vehicle use and slash car emissions, according to Farber. “Who knows exactly what ‘coordinate transportation’ means, right?” he says. “So if you could even start to move things using that power, it could be pretty useful.”

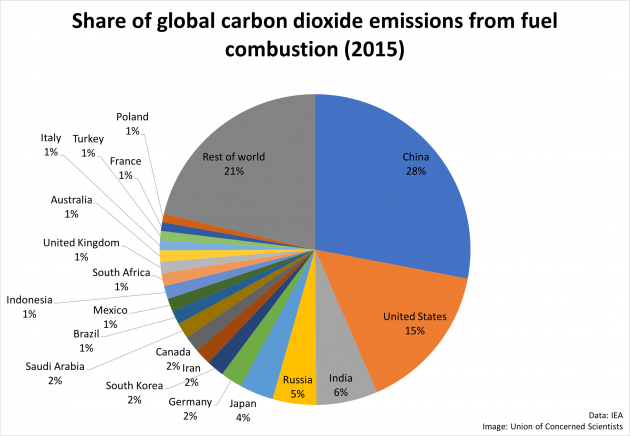

The largest source of greenhouse gas emissions from the United States comes from transportation and electricity generation, each with 28 percent of the country’s share of emissions, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. And, as Nevitt points out, the United States emits about 15 percent of the worldwide greenhouse gas emissions, second to China. So cutting down on our own greenhouses gas emissions could make a difference for the planet, even without coordinating with other countries (though an international climate agreement is certainly ideal, Nevitt says).

Union of Concerned Scientists, International Energy Agency

4. Overhaul trade with countries that buy and sell fossil fuels. Another step would be to invoke the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, a law which authorizes the president to regulate commerce with foreign countries after declaring a national emergency over “any unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States.” Climate change would meet that definition, Farber argues.

One specific application of that law could be to regulate coal exports. “We export a bunch of coal… It would be really useful if we could clamp down on that,” says Farber. “We should not be helping countries like India build new coal-fired power plants.”

Another option would be to institute sanctions limiting trade with certain polluter countries. “The president has international emergency economic powers, which we use for things like imposing sanctions on people or countries or different kinds of commercial transactions,” says Farber.

5. Motivate Congress to pass climate legislation. While this is the only step that doesn’t require legal wrangling, it might also be the hardest given the environment in Washington. That said, Nevitt notes that declaring a national emergency over climate change could still have a rhetorical advantage—an action that shows the country where a president’s priorities are. “The president has enormous authorities and enormous communications ability with the bully pulpit,” says Nevitt. “So using this nomenclature, this lexicon of ‘climate emergency,’ has certain rhetorical advantages to spark legislation or spark movement.” (Of course, Congress’ opposition to Trump’s wall and emergency declaration shows that the chamber doesn’t always bend easily to a president’s wishes.)

Environmental benefits aside, is a national emergency the best way, or even a good way, to deal with the climate crisis? Despite several experts laying out the specifics of what a president could theoretically do, each expert that Mother Jones spoke with sounded the same alarm: If the court upholds Trump’s emergency and approves his maneuver around Congress, it could open the door to potential abuses of power. “We should worry about the expansion of presidential emergency powers,” Farber says.

What’s more, “an emergency isn’t something you plan for,” says Kristina Costa, a former adviser to the counselor to the president in the Obama White House, who also served as a policy adviser and speechwriter on the 2016 Hillary Clinton campaign. “It’s something that happens unexpectedly and has to be responded to. We’ve known about climate change for a really long time, right? The impacts of climate change are in no way unexpected… It’s a real problem and it deserves a real solution.”

For Francesco Femia, co-founder of the policy and security research nonprofit Center for Climate and Security, declaring a national emergency over climate change would be so much of an authoritarian overstep that it isn’t even worth entertaining the hypothetical. When Mother Jones asked him what he would advise a president to do if they wanted to declare an emergency over climate change, he said, “I’d rather not answer.” He says that even if there was one step—like shutting down every single coal-generated power plant in the United States—that could immediately reduce emissions, “the damage that would do to the social fabric of the democratic system would be too great.”

Looking ahead to 2020, it’s unclear if any Democratic president would actually take the step to declare a national emergency over climate change. Even presidential candidate Jay Inslee, the Washington governor who is running on a platform of addressing climate change, told reporters last week that as of now, he wouldn’t want to use emergency powers to accomplish his climate goals if elected.

As Costa and Nevitt point out, finding a bipartisan legislative solution is probably the strongest (and most legal) route to addressing climate change. After all, the country’s bedrock environmental laws—the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act, for example—were all passed with the support of both Democrats and Republicans. “All those things have been enacted or voted on on a bipartisan basis,” says Costa. “And they achieved enormous good for the environment and for the US economy over the years.”

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Analysis, Climate Change