Should tech executives do hard time for violent content posted to their platforms?

By Matt Field | April 3, 2019

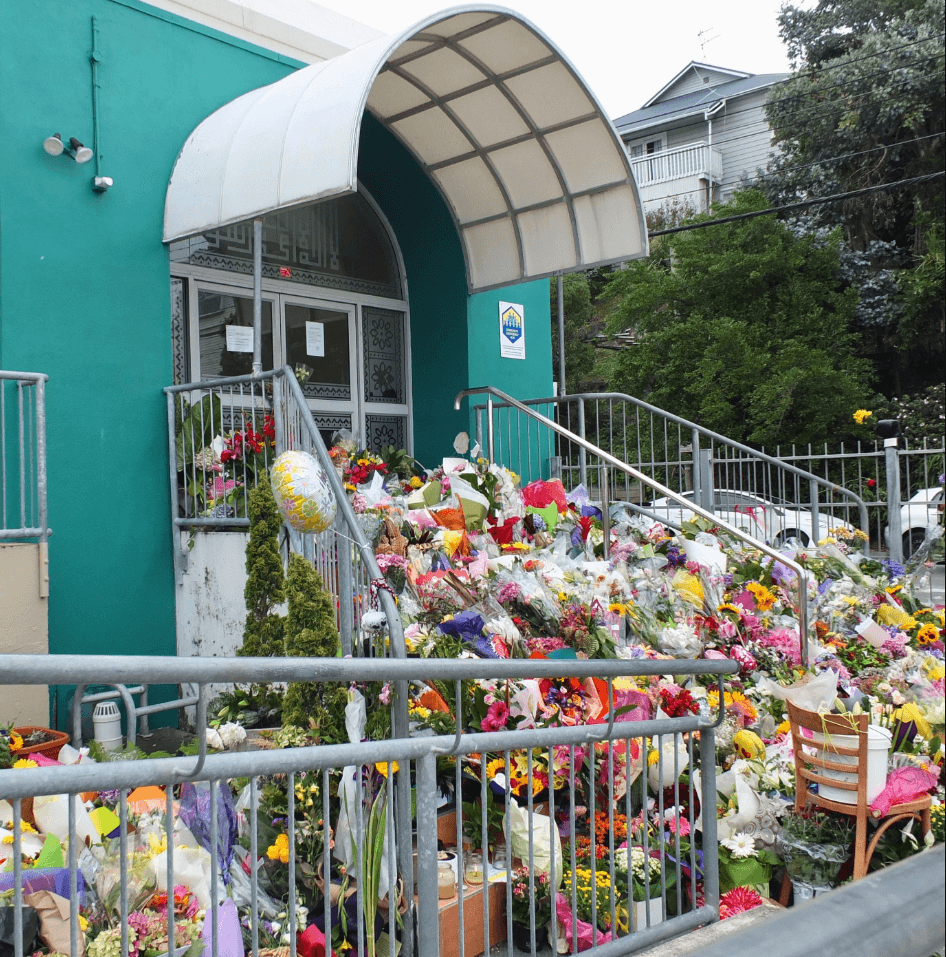

Flowers outside a mosque in New Zealand to commemorate the victims of an attack on two mosques that killed 50 people. Credit: Mike Dickison via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 4.0. (Edited)

Flowers outside a mosque in New Zealand to commemorate the victims of an attack on two mosques that killed 50 people. Credit: Mike Dickison via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 4.0. (Edited)

Following the massacre of 50 people at two New Zealand mosques last month, Australia’s ruling Liberal Party plans to introduce legislation this week to punish social media companies that don’t quickly remove violent content on their sites. New Zealand, where an Australian man used Facebook to livestream the mosque attacks, is also considering new regulations.

The major social media companies have weathered years of criticism about hateful content and propaganda on their sites. Mostly, they’ve responded by hiring more human content monitors or touting automated solutions. But the New Zealand attacks were further proof that the platforms haven’t managed to stop the problem on their own. And Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg sees the writing on the wall: Governments around the world are increasingly seeking to hold companies like his accountable for the content on their sites. In an op-ed in The Washington Post, he called for new regulation on harmful content.

“We have a responsibility to keep people safe on our services. That means deciding what counts as terrorist propaganda, hate speech, and more,” Zuckerberg wrote. “We continually review our policies with experts, but at our scale we’ll always make mistakes and decisions that people disagree with.”

In Australia, the government’s plan would mete out fines and even prison time if social media companies don’t take down “abhorrent violent material expeditiously.” (Videos of the mosque attacks could be found online even days later.)

“We will not allow social media platforms to be weaponised by terrorists and violent extremists who seek to harm and kill, and nor would we allow a situation that a young Australian child could log onto social media and watch a mass murder take place,” Australian Attorney General Christian Porter said.

Facebook executive Sheryl Sandberg echoed other tech officials by saying that people will inevitably bypass the content restrictions the companies put in place. In an open letter in The New Zealand Herald, she said Facebook had found at least 900 versions of the shooting video, edited to make detection by the platform’s automated content monitoring system more difficult. “People with bad intentions will always try to get around our security measures,” she wrote. She proposed new company-imposed restrictions on livestreams.

In the United States, where Facebook and other major social media companies are based, even if the federal government wanted to regulate online content, it would have to grapple with the First Amendment and its broad protection of free speech rights. That’s not as much an issue in places like Germany, where promoting neo-Nazi content, for instance, is banned. The US government can restrict speech that is intended or likely to incite “imminent lawless action.”

Since the 1990s, US internet companies like Facebook haven’t been treated like publishers who are liable for the content they publish, but like phone companies that aren’t legally responsible for what people say using their services.

In that respect, it’s significant that Zuckerberg is clamoring for government regulation on content, but not surprising. Other countries—Germany with its new social media hate-speech law and the European Union with a new privacy protection regime—are already regulating Facebook and its competitors. Regardless of what happens in the United States or Australia, Zuckerberg’s hands have already been forced. He alluded to this point last spring at a congressional hearing.

“As we’re able to technologically shift towards especially having AI proactively look at content, I think that that’s going to create massive questions for society about what obligations we want to require companies to fulfill,” Zuckerberg said. “And I do think that that’s a question that we need to struggle with as a country, because I know other countries are, and they’re putting laws in place. And I think that America needs to figure out and create the set of principles that we want American companies to operate under.”

Publication Name: Financial Times

To read what we're reading, click here

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Australia, Christchurch, Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg, New Zealand, livestream, mosque attack, social media

Topics: Disruptive Technologies, What We’re Reading