Ahead of 2020, disinformation and fake news are alive and well on social media

By Matt Field | August 15, 2019

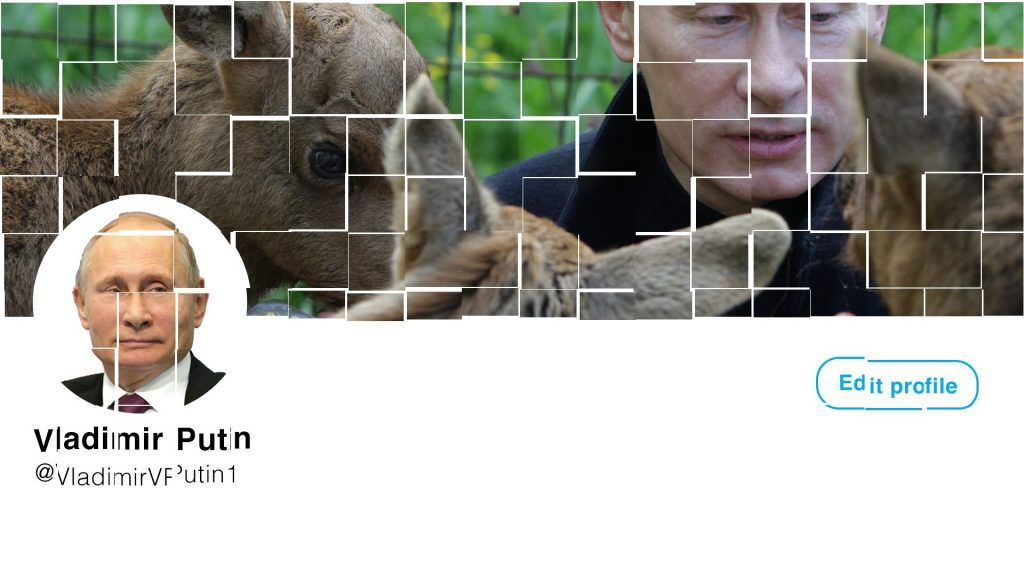

Photo illustration by Matt Field based in part on photos by premier.gov.ru and www.kremlin.ru via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 4.0.

Photo illustration by Matt Field based in part on photos by premier.gov.ru and www.kremlin.ru via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 4.0.

Watching the crowded field of Democratic presidential contenders spar over health care plans and criminal justice records, it can be easy to forget that the big show, the presidential election, is still far off. Eventually, only one Democrat will face Donald Trump, and when that happens, it won’t just be US voters taking sides, but governments around the world.

As in 2016, experts expect, Russia and others will attempt to interfere in the next election. If anything, an article in The Atlantic notes, the incentives for doing so are even higher this time around. A “Donald Trump presidency isn’t some pipe dream or fuzzy nightmare, as it was for many foreign governments during the 2016 race,” Uri Friedman writes. “It is instead an all-consuming reality that is disrupting America’s alliances, role in the world, and relationships with great powers like China and Russia.”

In a sign that online disinformation campaigns could blossom again in 2020, foreign governments, led by Russia, have regularly been promoting disinformation to achieve their political goals, a July report by Princeton researchers cited in the The Atlantic suggests. Researchers combed through a wide array of news sources and expert reports to develop a database of 53 instances of a governments pushing content in other countries that was made to appear as “indigenous to the target” country. Run between 2013 and 2018, these campaigns were pushed in the media of the target countries, including on social media.

The study shows that the bulk of the foreign influence efforts since 2013 have targeted the United States. Most of the efforts the Princeton researchers identified sought to defame people or institutions, or to persuade people one way or another on an issue.

Facebook and Twitter have touted their efforts to counter these sorts of disinformation campaigns and disable the accounts behind the content. One key effort that Facebook rolled out to combat the fake news proliferating on its network was a fact-checking program. While the company has arrangements with dozens of organizations around the world, it appears the program has a mixed record of success. When a fact-checking organization marks a post as false, users who want to share it are told so and are directed to accurate information. Facebook also suppresses the spread of false posts on the network.

A Poynter Institute blog post on the process highlighted instances in which false information had much greater engagement than fact-checks. One meme claiming that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Democratic leader Chuck Schumer helped former President Barack Obama fork over $150 billion of US funds to Iran had almost 200,000 engagements. The fact-check meanwhile, had just 4,500. (The nuclear deal with Iran unfroze $150 billion in assets that belonged to Iran.)

During his presidency, Trump has frequently assailed the news media and pushed conspiracy theories, and the news media has duly fact-checked him, which the president has regularly decried. As a result, being fact-checked or in some other way regulated by the big social media platforms can be something of a badge of honor among his biggest online fans.

Case in point: Terrence K. Williams, a comedian and commentator, pushed out a conspiracy theory that politically connected financier Jeffrey Epstein didn’t commit suicide in jail while awaiting trial, but rather might have been targeted for murder by the Clintons, part of the so-called #ClintonBodyCount. Williams posted his allegation to Twitter and Facebook, prompting a re-tweet from Trump, as well as a fact-check from Facebook.

Williams made the most of both the re-tweet and the fact-check. In the latter case, he responded by posting a video urgently proclaiming that, “Facebook is after me.” In the Twitter version of the post, he urged his followers to promote the video in order to get it trending on the platform. “Please President Donald Trump, do something about this free speech stuff. They are coming after conservatives and Trump supporters because 2020 is around the corner and they are trying to shut me down,” Williams said. “If anything happens to me ya’ll, just know somebody on the left did it, somebody that don’t like Trump did it.”

As with his initial post about Epstein, Williams’ video was shared tens-of-thousands of times on Twitter.

Publication Name: The Atlantic

To read what we're reading, click here

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.