TILTING TOWARD WINDMILLS

A homespun Rhode Island destination gets an offshore wind farm—and, mostly, likes it. Will massive offshore wind parks follow, powering America’s Northeast?

A Bulletin special report by Dan Drollette Jr.

The Block Island wind farm. BOEM video excerpt

A Bulletin special report by Dan Drollette Jr.

To learn more about the latest in offshore wind power, you have to go offshore—specifically, to the waters just off Block Island, Rhode Island. Here, one of the biggest experiments in renewable energy in North America is wrapping up, setting the stage for what could be a rapid explosion in the number of commercial offshore windmills on the entire East Coast of the United States, assuming they leap the latest set of ever-changing legal hurdles set by fossil-fuel friendly regulators in Washington, DC. The goal of the Block Island test wind farm—which started construction in the summer of 2015 and started generating some power in December 2016—is to see if it is technologically, environmentally, and scientifically possible to transfer offshore wind power technology from Europe to North America. (So far as the political and legal aspects go, see sidebar, “You can spot the pioneers by the arrows in their backs.”)

But to see the wind farm, you first have to get there.

So I am traveling to Block Island from the nearest port on the mainland: Point Judith, Rhode Island. Located on the north side of Block Island Sound, Point Judith sits at a marine crossroads: southwest takes one to the tip of New York’s Long Island, while northeast leads to the approaches of the calm, flat waters of Massachusetts’ Cape Cod Canal. Roughly 13 miles due south of Point Judith lies the island that Dutch explorer Adriaen Block discovered just over 400 years ago and named after himself. The trip takes about 30 minutes on this small high-speed catamaran ferry, the MV Athena, which carries no cars or other bulk goods—just people, a few groceries, and some of the bicycles that seem to outnumber trees on Block Island.

Because I’m making the trip in early October, it’s quiet—not truly off-season anymore in these days of climate change, but close. That means some businesses are still operating, but it’s easy to find a space in the parking lot, and there are fewer than two dozen people in the interior of the ferry’s top-most deck, where the coffee shop is located.

Any beach community at this time of year carries a touch of melancholy, not altogether unpleasant, and Point Judith is no exception. The empty beaches, deserted hot dog stands, and shuttered clam shacks speak of a summer gone by. Still, it’s a warm and sunny day for early autumn, with calm, exceptionally clear skies that let one see for miles. And there’s still the screech of seagulls, the taste of salt in the air, and the smell of a mixture of diesel fuel and seaweed at low tide.

Looking west at Block Island, with its five offshore windmills; north is to the right in this aerial photo. The tip of Long Island can just be made out on the far left horizon; immediately behind Block Island on the right one can make out the line of white surf that marks the Connecticut shoreline. Deepwater Wind

The ferry is not too far out to sea before I make out the blue-gray form of Block, followed by something new: five high-tech windmills, about four miles east of the island’s iconic lighthouse, known as Southeast Light. I try to take a picture, but when I step outside onto the bow with my cell phone camera, the wind is so strong that I must lean far forward to keep my balance. The phone’s flat surface catches the wind like a sail, and I nearly lose it overboard. The near-miss serves as a reminder: As locals tell me repeatedly in the next few days, don’t underestimate the power of the wind and the sea around here.

Case in point: The first man to single-handedly circumnavigate the globe, Joshua Slocum, likely sank somewhere here in Block Island Sound after his converted 36-foot oyster boat, “Spray,” foundered. Slocum had successfully crossed the South Pacific, survived encounters with cyclones, rogue waves, night-time attacks by pirates, and rounded Cape Horn and the Cape of Good Hope—only to disappear below Cape Cod in 1909, shortly after setting sail from his nearby farm.

A real-world experiment in offshore power, paving the way for wind farms 600 times larger

Block Island may be home to the smallest town (New Shoreham) in the country’s smallest state, but big things have happened here. Since December 2016, the seas off this speck of land in the Atlantic Ocean—Block Island is under 10 square miles in area, or less than half the size of the island of Manhattan—have been the proving grounds for the privately funded firm of Deepwater Wind, the primary driving force behind the first and so far only commercial offshore wind farm in North America.

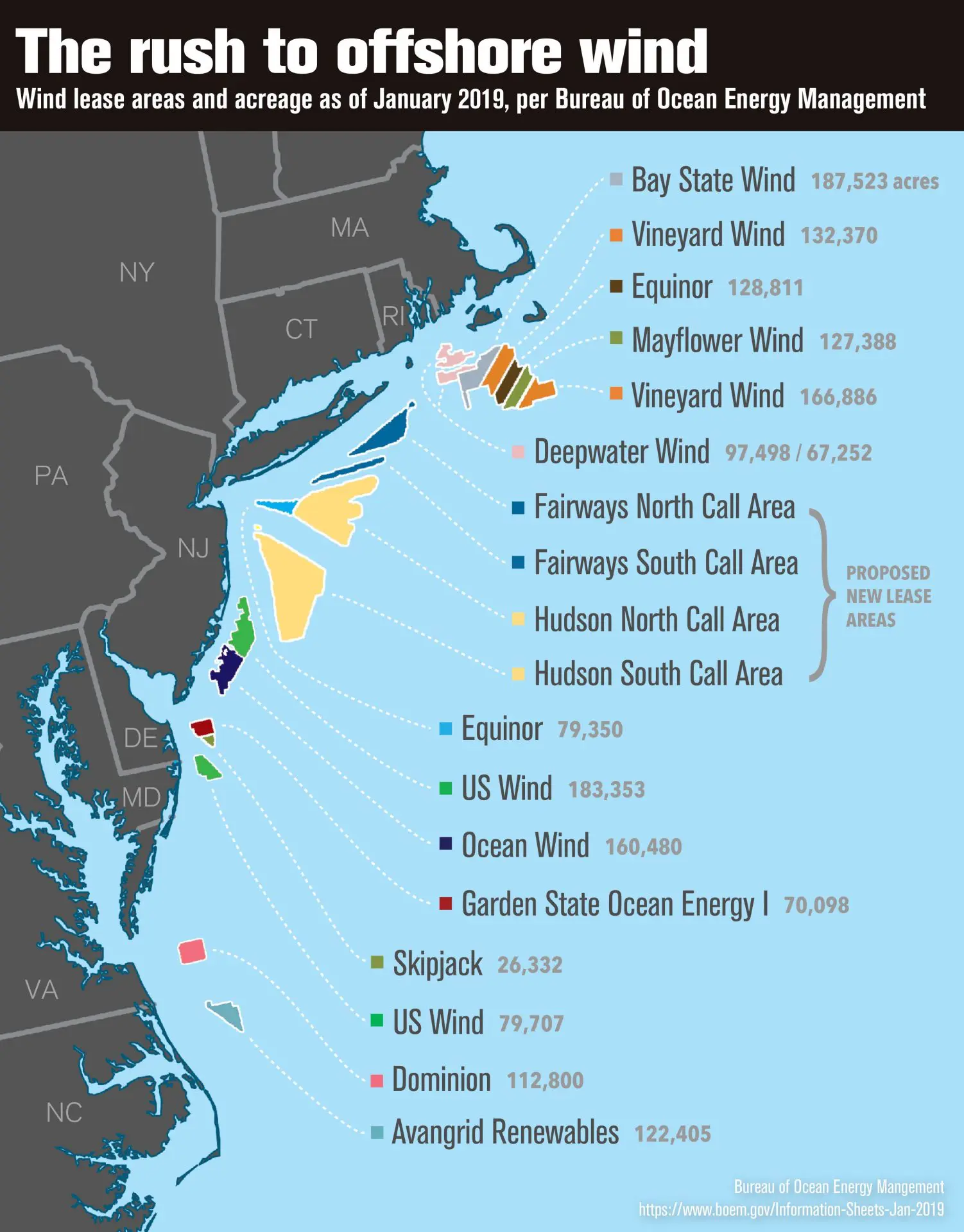

This five-turbine, 30-megawatt endeavor has been effectively acting as a multi-year, real-world experiment in offshore wind power for the United States, paving the way for offshore wind farms on the northeast coast and the mid-Atlantic that could each be as much as 600 times the size of this test site, with hundreds of turbines generating electricity for hundreds of thousands of homes from just one full-scale, industrial-sized wind farm. There are more than a dozen large offshore “wind lease areas” suitable for wind farms currently up for bid from the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, stretching from Massachusetts to North Carolina.

Massachusetts alone is soliciting contracts for 1,600 megawatts of offshore wind development (half have now been sold), which is more than 50 times the size of this pilot project off of Block Island. (Because it is the region’s financial powerhouse, and its major cities represent a large market of potential wind power consumers next to the coast, the doings of Massachusetts dominate the conversation of little Rhode Island next-door.) Once it is built and running, the Massachusetts project off Martha’s Vineyard alone will provide enough energy to power at least 230,000 households, or about a third of the state’s residential energy demand. Other states are working on a similar gargantuan scale. All told, there are 28 offshore wind projects in the works on the East Coast, with a total capacity of 24 gigawatts, or 24,000 megawatts. To give a sense of the massive size of the generating power of the wind farms now in the works, the first commercial civilian nuclear reactor in the United States—Massachusetts’ Yankee Rowe Nuclear Power Station, now decommissioned—generated just 185 megawatts at its peak.

But after decades of false starts and tangled litigation, a sea change appears to be occurring for offshore wind in the United States, as this country races to catch up with Northern Europe, where this renewable energy source has become increasingly mainstream and increasingly cheap. A 2015 US Energy Department study predicted that America’s offshore wind production will grow from 30 megawatts today to 22,000 megawatts by 2030, providing as many as 80,000 American jobs. Literally billions of dollars are at stake. And these offshore wind projects could have a big impact on the environment. The Union of Concerned Scientists estimates that the newly contracted wind farms would offset carbon emissions equivalent to removing about 270,000 cars from the road. They could play a key role in reducing the region’s climate change footprint, while allowing the New England economy to grow. Already, the business section of the New York Times has run articles on how the coming boom in wind power could revitalize struggling, down-at-the-heels towns such as New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Thomas Gaulkin / BOEM

Consequently, this handful of windmills in one test plot have been closely watched, studied, and debated, from multiple points of view, by many different “stakeholders,” as the parlance goes— including Wall Street analysts, investment firms, engineers, economists, sociologists, fisheries experts, environmental activists, historic preservationists, ornithologists, marine mammal biologists, Native American tribes, scallopers, long-liners, oystermen, sport fisherman, real estate investors, the tourism industry, and homeowners.

And, of course, lawyers. Many, many lawyers.

The rap against wind power, and pretty much any form of renewable energy, has long been that it is impractical because of it of its intermittence—that is, its perceived unreliability and unpredictability—and its expense. But from what I had heard, for at least one of those objections, matters had changed: The price of electricity generated by wind has gone down dramatically in the last few years, to the point where wind is now cheaper than nuclear power, and possibly even cheaper than coal, still the cheapest form of energy (depending on how one factors in variables such as efficiency, subsidies, clean-up, and the costs of “externalities” such as pollution, lung disease, and the amount of greenhouse gas produced). “Customers save money when utilities replace existing coal with wind or solar,” reported Forbes magazine in December 2018, in a story tellingly headlined “Plunging Prices Mean Building New Renewable Energy Is Cheaper Than Running Existing Coal.”

The promoters of this offshore wind project had promised the islanders that their electric bills would go down by about 40 percent once it was in operation; I wanted to see whether that had proven true, and how satisfied they were with their new power supply. And what had the presence of this small wind farm done to the island’s views of the sea, and therefore its tourism, a mainstay of the island’s economy for at least a century-and-a-half?

And there were concerns about what it might do to the fishing—not an idle consideration on the docks of fishing ports on the mainland. Erwin Veit, skipper of the 125-foot long-line tuna boat Vera out of New Bedford, told me: “The last thing I want is to have to be slaloming through a field of windmills in 30-foot seas during a heavy storm, while carrying 600 feet of gear behind me.”

But probably the most important questions involved the why of it all—why was Block Island, a lesser-known, if still very desirable island my family used to visit on summer weekends when I was a kid, chosen? Block Islanders are well-aware that their isle offers a different draw than the Hamptons, Nantucket, or Martha’s Vineyard. The words that one local official used to describe Block Island, if with a shudder, were “quaint” and “old-fashioned”—and I could certainly agree with that, so far as quick descriptions go.

In my memory, Block Island was sort of like going to visit your grandmother’s. It was a place of wide porches facing the sea, no air conditioning, few televisions, the occasional brownout, and somewhat intermittent phone service—which meant more time spent socializing, in-person, one on one. Back then, it was the antithesis of current destinations with high-speed internet and reliable cell service. And I had loved it for the things it was not: not overly hyped, not a gated community (though it does have some very expensive homes, good restaurants, and famous denizens), not subject to prepackaged mass tourism. Even now, many of the hotel rooms don’t have alarm clocks, and no 5,000-person cruise ships dock in Block Island’s harbors—so far. Rather, on this island, the fastest, cheapest, and easiest transportation was often by bicycle; it was where 40 percent of the land remained a protected nature reserve, where the local movie theatre was a converted nineteenth-century wooden roller skating rink, and where the major attraction of the downtown landmark Surf Hotel was its porch, where you could rock in a chair facing the harbor and watch the ferries come in. Or maybe if the weather turned, you might sit indoors by the fire and play with the proprietor’s King Charles Spaniel puppies.

I’d have to find out where things stood, now that the wind turbines had come.

“The last thing I want is to have to be slaloming through a field of windmills in 30-foot seas during a heavy storm, while carrying 600 feet of gear behind me.”

Looking west at Block Island, with its five offshore windmills; north is to the right in this aerial photo. The tip of Long Island can just be made out on the far left horizon; immediately behind Block Island on the right one can make out the line of white surf that marks the Connecticut shoreline. Deepwater Wind

The distinctive architecture of this windswept island, with its emphasis on porches, can even be seen in the most modern buildings. Dan Drollette Jr.

Thomas Gaulkin / BOEM

You can spot the pioneers by the arrows in their backs

The long, twisted story of US politics and offshore wind farms.

Scandinavia and the Netherlands are the leaders in the race to develop bigger, better, more efficient windmills. Part of the reason for this may be cultural: There is little resistance in northern Europe to the sight of windmills on the horizon; no one in Denmark seems particularly exercised about the endless row of turbines a couple of miles off of Copenhagen. Similarly, the Netherlands has long had a love affair with windmills; walking through a quiet upscale suburb of Amsterdam one Saturday afternoon, I found the enormous pylon of a huge modern windmill tucked in among the expensive homes, luxury cars, manicured hedges, and billiard table-like lawns. Holland even holds a National Windmill Day.

Not so in the United States, where there seems to be a visceral dislike of the sight of windmills on the horizon among those in the upper-income tax brackets—as can be seen in tracing the long, twisted story involved in getting federal approval for offshore wind farms...

The local movie theater on Block Island. When it was being renovated in the late 1980s, old posters for silent movies and traveling stage shows were found—including one, The Pink Lady (below), that debuted while the Titanic was still being built. Dan Drollette Jr.

The Danish are coming, the Danish are coming

Illustration from GE, showing the planned largest windmill in the world, next to the Eiffel Tower and the Chrysler Building.

Middelgrunden offshore wind park, outside Copenhagen. Wikimedia via Creative Commons License

Looking out a bedroom window at the National Hotel. Dan Drollette Jr.

Some hardy souls on Block Island's Crescent Beach, seated less than 100 yards from the place where an underwater cable connecting the island to the mainland emerges from the sea. A set of small white buoys just visible in the surf marks the cable’s approach to the island. Dan Drollette Jr.

On a global level, offshore wind power has been quietly taking off in a big way, partly because of concerns about carbon emissions, but also because of massive changes in technology. A new generation of high-efficiency, lightweight, ultra-modern designs has emerged, using the latest in carbon-fiber technology to make truly immense windmills—towering as much as 600 feet above the ground, or about twice the height of the Statue of Liberty as measured from the bottom of the statue’s pedestal to the tip of its upraised torch. Some windmills have individual rotor blades that are 270 feet long—the same as the wingspan of the world’s largest commercial plane. Just moving a single rotor blade of that size from the factory to its final destination is a challenge; the internet is full of videos that show things like a truck loaded with a turbine blade making a 90-degree turn onto a bridge. Meanwhile, construction of the biggest wind turbine in the world is underway outside the city of Rotterdam; it will stand 850 feet from the turbine’s base to the tip of the topmost blade. If put next to one of New York City’s tallest buildings, it would touch the foot of the mast atop the Chrysler building.

Windmill builders go for this kind of scale because of a simple law of physics: Double the length of a rotor blade, and it will generate eight times more energy. And the more energy you can generate from a given structure, the lower it costs to operate, and the more money you can make.

And money ultimately plays a large role in what’s driving the race towards wind power, possibly equaling that of the urge to get serious about cutting down carbon emissions. Consequently, for the past three decades or so, there has been a sprint towards taller windmills with longer rotor arms; the largest modern offshore windmill—also known as a turbine—generates about 20 times more power than its 1980s grandfathers.

Illustration from GE, showing the planned largest windmill in the world, next to the Eiffel Tower and the Chrysler Building.

Curiously enough, the leaders in the windmill race are not the Dutch, as one would expect (although the Netherlands is still a top contender, with just under 2,000 working windmills scattered up and down the country). Instead, the world’s leaders in wind power these days are the Danes. Everywhere you turn, there seems to be a Danish connection: manufacturers with Danish names, investment groups with titles such as Danish Oil and Natural Gas, along with Danish pension funds. (Deepwater Wind itself was acquired in 2018 by the North American branch of the $9 billion Danish consortium known as Ørsted. But Deepwater is hardly the only investor in the Block Island Wind Farm; participants also include GE Energy Financial Services and Citigroup.)

The Danes have long been the world leader in wind power. At times, says Wind Denmark, the trade magazine of the Danish Wind Industry Association, Denmark’s wind energy provides for more than half of that country’s electricity demand, and the Danish government is aiming for wind and other renewables to provide 100 percent of Denmark’s energy supply by the year 2050. The reasons for this go all the way back to the 1970s Arab oil embargo, when the price of a barrel of oil skyrocketed and Denmark went on a tear to pursue this form of alternative energy—accelerated by a growing domestic anti-nuclear power sentiment—and began to tap into the Baltic Sea’s large supply of steady and relentless, if not particularly speedy, wind. It took a while to get the kinks worked out; some of the initial windmills made by the Danes in the 1970s broke or fell apart—and were hugely inefficient by today’s standards, with blades only 15 feet long. But with practice and testing—and prolonged encouragement from the Danish government—the Danish wind turbine industry improved, and the country eventually became the world’s largest manufacturers of the machines; Danish companies such as Vestas and Siemens Wind Power now dominate the field.

And now, that technology is poised to come to America.

In May of 2018, after decades of epic legal battles (and after the first results from Block Island came in), Massachusetts signed its first offshore wind contract with the firm of Vineyard Wind—yet another Danish-led project, this one spearheaded by Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners—for 100 windmills. They will produce 800 megawatts of power in their particular wind farm in the seas south of Martha’s Vineyard, roughly 51 miles northeast of Deepwater Wind’s Block Island pilot project as the gull flies. And Boston is eager for energy; already, Massachusetts pays some of the highest electric bills in the continental United States—only Hawaii pays more. The same week that Massachusetts awarded its first commercial wind farm lease, Rhode Island awarded a contract to Deepwater Wind to move up from its current 30-megawatt test wind farm to a 400 megawatt, 50-turbine project. And New Jersey passed a new law aiming for 3,500 megawatts of offshore wind power. (To give a sense of the massive scale of these projects, Hoover Dam generates 2,000 megawatts.) Connecticut, Maryland, New York state, Delaware, and Virginia are also planning expansive offshore wind complexes. Environmentalists were jubilant; “We could run the whole East Coast on offshore wind,” Amory Lovins of the Rocky Mountain Institute told The New York Times.

When the ferry lands at Block Island, the weather has changed dramatically, and the Coast Guard has issued small craft warnings, meaning that there is little chance of getting out to the windmills themselves today. I check into the rambling old wooden National Hotel on the main street of the main village, known as Old Harbor. I find that my room is a bit old-fashioned but with a sort of severe, stark charm—and a glorious view of the harbor. Here and elsewhere over the next few days, I will have the repeated feeling of having stepped into an Edward Hopper painting.

On the door, I see a notice posted at eye level: “Block Island has one of the highest electricity rates in the country. Please turn off all lights and other electrical items.”

They weren’t kidding. In 2008—nearly a decade before the wind farm came on-line—the average homeowner on the island paid 61 cents per kilowatt-hour for electricity, with businesses paying as much 70 cents, plus various fees and surcharges. (This was not a new phenomenon, a 1998 Wall Street Journal article said that Block Island was on the verge of paying the highest power bill in the entire United States.) And this was at a time when the average mainland Rhode Islander paid 15 cents per kilowatt-hour, and Midwesterners—home of the monstrously big coal-fired plants—were paying half that. The owner of the island’s historic Spring House hotel (established 1852) lamented the situation to the Block Island Times, telling the newspaper his electric bills had shot up to $30,000 per month. (No, that’s not a typographical error; it really was $30,000 per month.)

Why Block?

Adirondack chairs facing the sea at the Spring House Hotel, in continuous operation since 1852. At times, walking around the island in the off-season felt like stepping into an Edward Hopper painting. Dan Drollette Jr.

Down the street from my hotel, the menu of the Mohegan Cafe carried a notice lauding “our celebrated offshore wind farm,” and the free, 116-page Block Island Guide tourist guidebook said on page 21 that the turbines “are well on their way to becoming an enduring symbol of this place, much as the Eiffel Tower now is for France. The turbines have been supplying all of the island’s power since May 2017.” The bulletin boards of the local supermarket included at least six different narrated tours of the windmills. One notice is from an anthropologist at the University of Rhode Island, looking for comments about decision-making and tourism on the island.

As I wait for the weather to turn, over the next few days I visit the local newspaper, the tourism office, the ferry office, the library, and the history museum, among others. Because it is off-season, shop owners and sales clerks have time to chat, so I catch up on little bits of folksy news: Aldo Leone, the local baker, still sends out a guy in a dinghy at ungodly hours of the morning to sell fresh pastries to potential customers on their boats in New Harbor; to pass the time, he sometimes sings in Italian. Consequently, boaters anchored there were often startled awake to the eerie and unexpected sound of “doughnuts, doughnuts” coming out of the white morning mist, accompanied by strains of Pagliacci. Sometimes boaters do not appreciate being awakened in this manner.

But everyone I talk to seems upbeat about the windmills. In fact, the biggest surprise of my visit may have come from the mouths of Bill Padien and Ann Hall, of the Block Island Bagel Shop. When asked their opinions of the new wind farm, the words they used were “beautiful” and “sculptural.” Padien waxed eloquent about what it was like to fly in an airplane and see the tops of the windmills emerge from the bank of clouds below, while Hall extolled the fact that there was no longer any need for a loud and smelly diesel generator in the heart of town to provide electricity. “A friend of mine lives near there, and she’s so happy...” she says. “She can actually hear the birds.”

After power switched over to the wind farm, the island's diesel generator was shut down ceremoniously (be sure to turn the audio on!). Block Island Power Company

The reason that Deepwater Wind chose this spot for tests of wind power is the same reason that old-timers on the island chose to erect so many windmills here so long ago: Prevailing winds in this part of the world generally run east to west, meaning that they come from most of the way across the ocean before striking landfall in the form of Block Island and its neighbors. Consequently, the island and its surrounds have some of the strongest, most consistent winds in the world, making it “the Saudi Arabia of wind.” What’s more, by the time the wind gets here, it has traveled an extraordinarily long distance over the water in a single direction (technically known as “fetch”) without encountering any obstacles to disturb it; in other words, it has what one Deepwater Wind employee called “good quality, very pure wind.” He added: “When you hear a turbine going ‘chop, chop, chop’ or ‘whoop, whoop, whoop’ and stuff like that, that’s because of dirty wind, or wind that’s been corrupted by the terrain. It sort of bounces around and swirls and whirls. If you can hear a turbine, then it’s not working right.”

In addition, the south coast of New England lies a relatively short distance from major cities, cutting down on the amount of expensive undersea cables to be laid. And on land, in many cases power companies can piggyback on existing infrastructure, in the form of the high-tension power lines built for decommissioned nuclear plants or retired coal-fired plants such as the 1,500 megawatt Brayton Point Power Station on the mainland—the last coal-burning plant in Massachusetts, which was shut down in May 2017.

Later in the day, I bike up the hills of Block Island, to Southeast Lighthouse, or Southeast Light, which is open to the public. This is the island’s iconic symbol, an 1870s octagonal Gothic Revival brick-and-granite structure with an attached, similarly ornate, two-and-a-half story lighthouse keeper’s cottage, both of which are perched atop one of the highest cliffs on the island—Mohegan Bluffs, 200 feet above sea level. From here, there is an unobstructed view of the offshore windmills. They do indeed change the seascape on this slightly overcast day, but not as much as I’d imagined: When I stretch out my arm, I can block the sight of one with my palm.

Long deactivated, Southeast Light had been neglected for years and was in danger of tumbling into the sea after centuries of erosion had eaten away the bluffs to the point where the light was only 55 feet from the edge. (It was originally about 300 feet away, say historians.) A local group of volunteers formed a non-profit foundation to save the lighthouse and move the structure 230 feet inland.

Lisa Nolan, one of the driving forces behind preserving the island’s Southeast Light. Dan Drollette Jr.

I’m admiring the facade of Southeast Light when the current head of the lighthouse rescue group, Lisa Nolan, emerges from a 1960s-era suburban ranch-style building about 100 yards away. We have to raise our voices to hear each other over the howl of the wind, which seems to have picked up greatly in late afternoon, as usual. But she tells me a bit of the future plans for the building, which include things such as homestays—in which tourists would pay for the privilege of living in the ornate keeper’s cottage and attending to the round-the-clock duties of a typical employee of the 19th-century US Lighthouse Service, as the organization was known before it merged with the Coast Guard in the late 1930s.

When asked her feelings about the loss of the pristine view, Nolan seems hesitant to answer; later I learn from a Deepwater Wind employee that the company had donated a “significant amount of money” to compensate the historic society. Nolan does tell me, however, of a new twist she’s noticed among the site’s visitors: “Sometimes they walk right past the lighthouse to see the windmills.” She sighed. “They even bring lawnchairs and set them up on the grass to look out at them, ignoring the lighthouse completely.”

On another visit to Southeast Light, I was to see a group of about a dozen people on the edge of the cliff, all clustered around someone giving a talk about what they can see. It turns out that they are from the Nature Conservancy—the island is a major stop for migrating birds on the Atlantic flyway—here to learn more about wind farms and their impact on birdlife. (Answer: Windmills have minimal impact, especially when compared to the effects of fossil fuels, such as global warming, and oil spills.) Their host seems well-equipped with handouts, photos, and an impressive array of facts: “The turbine blades are from Denmark, the pylons from Spain, the cable from South Korea; each windmill is 0.6 miles apart. The windmills did not cause any collapse in housing prices on Block Island... This is not gonna save the world, it’s just a small project. But it is a big step—and it’s very visible.”

It turns out that the speaker is Bryan Wilson of Deepwater Wind, well-known on the island and regarded as someone who can talk your ear off on all things wind-related—as I was to confirm later in a 3-hour interview in his harborside office about the technicalities of wind turbines. (See sidebar: “When you hear a turbine going ‘whoop, whoop, whoop.’”) But for now I simply listen in, while the windmills turn in the middle distance, a pair of large cargo ships go by on the far horizon, and a sportfishing boat passes in the foreground. Enthusiastic about his subject, hearty, tall and bearded, with graying windswept hair, Wilson looks oddly familiar. I suddenly realize why: He was the subject of a full-page Citi ad for wind energy on the back cover of Time magazine.

Adirondack chairs facing the sea at the Spring House Hotel, in continuous operation since 1852. At times, walking around the island in the off-season felt like stepping into an Edward Hopper painting. Dan Drollette Jr.

A 1981 Journal Inquirer story about Aldo Leone.

Lisa Nolan, one of the driving forces behind preserving the island’s Southeast Light. Dan Drollette Jr.

When you hear a turbine going “whoop, whoop, whoop”

The offices of Bryan Wilson, the Block Island Wind Farm’s manager, overlook the water, with spectacular views of the harbor traffic. Crammed with helmets, lifejackets, fluorescent vests, carabiners, WD-40, maps, “No mooring” signs, and unidentifiable marine gear, the space recalls Quint’s harborside shack in the movie Jaws.

Wilson loves talking about wind power, and our scheduled interview goes on nearly three times longer than planned, as he whips out facts and figures and locates photos, studies, and diagrams. At one point, he even drags out a two-foot-long sample crosssection of undersea cable—a piece of multimillion-dollar technology in itself...

“This is not gonna save the world, it’s just a small project. But it is a big step—and it’s very visible.”

Bryan Wilson was the face of a Citi print ad campaign for the Block Island wind farm. Dan Drollette Jr.

Killing the view?

Driving away the tourists?

Rhode Island Sea Grant / University of Rhode Island

The next day dawned nice and clear, so I called a number of charter boat captains about “driving out to the windmills,” as one of them put it. The response of Chris Hobe of “Fish the World Charters” was typical: Small craft warnings were still out, and one should not be fooled by a bit of blue sky. Even when it’s passable on Block, conditions can be extreme on the open water.

So instead of visiting windmills, I interviewed Jessica Willi, executive director of the Block Island Tourism Council, located at the town airport. Block Island State Airport pulls in a fair number of people with serious wealth, as evidenced by the expensive small planes parked on the tarmac and the magazines in the airport lounge with titles like Elite Traveler: The Private Jet Lifestyle Magazine, which carried stories on superyachts and $249,000 watches.

After minor pleasantries, Willi tells me of a University of Rhode Island study of Block’s wind farm, funded by the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, scheduled to come out in a few months. The study is composed of several smaller studies, including a three-year sampling of public opinion by cultural anthropologist Amelia Moore on approval or disapproval of the wind farm, and whether it went up or down over time. (Answer: up.) Moore’s study began when the turbines were just being put in; now that several full tourist seasons have gone by, results were starting to come in about the effect on the “viewshed.” In Willi’s opinion, such a meta-study—which included a look at the wind farm’s effects on tourism—is great: “When a company is talking about coming in and building a wind farm offshore, and the powers-that-be say ‘not in my backyard because it’s going to affect tourism,’ they can show the study ... and the end result, if anything, [showed] it probably improved tourism.”

Willi says that there are definitely people who come to Block Island just to see the wind farm, but adds: “It’s probably less than 100 people that come specifically to see it. And we have 1.3 million visitors a year, so it’s not like a huge percentage of people, it’s not making or breaking the economy... 99.5 percent of people tell us it’s not affecting their visit to Block Island. So it’s probably a net wash.”

From her point of view, even such a neutral outcome is a relief; tourism revenues provide much of the money the town needs for roads, schools, health care, emergency services, the town library, and just about everything else. Whether it’s day-trippers or full-time summer cottage people, it’s those 1.3 million yearly tourists to Block Island who pay the taxes that support the community, not the tax revenue from the island’s thousand or so year-round residents. An increasing number of those tourists have been coming from the wealthiest one-percent of the population—so there were legitimate worries about what they would think of a wind farm in the viewshed.

In at least one case, the value of a home facing the offshore windmills went up, not down. “I’ve actually had people say that they’ve been given offers on their house because they have views of the wind farm,” said Willi. “But I think that’s somebody trying to prove a point. Because there’s like two neighbors out there, and one’s super pro-wind, and one’s like the most anti-Block Island wind farm. And they are neighbors, and so I think they’re trying to prove a point to each other.” She added: “But the great thing [about the coming of the wind farm] is that it’s stable energy.”

Her assertion, of course, goes against the primary criticism of renewables. But the electricity situation here is complex: If Block Island had been able to simply pay the estimated $25-to-$40 million on its own for a 22-mile-long submerged power cable buried 6 feet under the ocean floor from the nearest substation on the mainland—without the wind farm, just having the regional electric company known as National Grid provide the electricity from the mainland—islanders would have also seen the arrival of stable power. But the island had petitioned for such a cable for decades, without any luck, and there was no way they could have paid for it on their own. Better to let the wind farm do it.

Still, Willi is an islander and eventually talked about the wind farm from that point of view, rather than as someone concerned about tourism numbers and how to compete with Martha’s Vineyard or the Hamptons. “What was lost by the advent of the windmills is sort of very intangible,” Willi says. “There was something about going to the Southeast Lighthouse or standing on the bluffs, with a view of nothing but the sea and the stars. It’s really hard to describe, it’s a feeling you really only have if you’ve lived on Block Island for many, many years, and you’ve been to that spot a hundred times. You go up there and look out at the ocean for whatever reason, and you get clarity or peace of mind. And now when you go do that, there’s something industrial there. And sad to say, they’re not beautiful—at least, not to me.

“And whatever you think about them, the reality is they’re there now, and they weren’t there before.”

Four of the five Deepwater Wind turbines as seen from Southeast Light, October 2018. Dan Drollette Jr.

Judy Mitchell

From several dozen interviews—long and short, in-depth and off-the-cuff, some of which made it into this story, and many of which did not—it became clear to me that the general rap against wind power was wrong, at least in this instance. On Block Island, the wind farm was pretty dependable as a source of energy, and the undersea power cable that accompanied it had provided a vital umbilical cord to the mainland, allowing the reliable source of power that islanders had long wanted. While prices had not gone down as much as people had hoped—partly due to the costs of putting up a substation and all the ensuing island infrastructure—Block Island was no longer one of the two most expensive places in the United States for electricity. If nothing else, wind had turned out to be more reliable than ferrying barrels of diesel fuel to a generator located on an island 13 miles out to sea.

From what I could tell, it also seemed that what had been learned about offshore wind was readily transferrable on a commercial scale, at least so far as engineering goes. True, the wind farm at Block Island is in an extraordinarily well-suited place for wind power, with near-perfect topography and fetch, and close to major population centers and markets. And even though the winds around Block are notoriously likely to ramp up quickly and become potentially destructive, the test site had weathered a major hurricane without a problem. So it will probably scale very well.

But it is hard to know what regular electric power (and the high-speed internet cable that came along with it) will mean for Block Island, culturally. After all, part of the appeal of an island is getting away from it all, and enjoying the scenery.

Toward the end of my visit, I go to the town library to use the internet, and I tell the librarian, Judy Mitchell, about my efforts to talk to as many islanders as I can about the windmills. The next thing I know I am grabbed by the elbow and introduced to everyone she can find in the building. I am hardly done with talking with Kay Lewis—who lives on Lewis Point near Southeast Light and says she loves the windmills—before another person tells me: “I’m a YIMBY about it, not a NIMBY.” (It takes me a while to figure out she means “yes in my back yard” about windmills, instead of “not in my backyard.”) There are so many positive responses—about a dozen or so in the space of an hour—that I almost start to suspect being set up. But that would be almost impossible on a spur-of-the-moment event, and the comments feel genuine.

If there is a common thread to the comments, it is that the windmills are quiet and distant, and that with a steady and predictable source of power, islanders no longer have to worry about blackouts or brownouts. With modern appliances, the latter is almost as bad as the former, because these days so many appliances are “smart” and contain microchips in some way, shape, or form—meaning that many furnaces, stoves, microwaves, refrigerators, windows, doors, alarms, power supplies and the like (not to mention desktop computers) are seriously disrupted when the power is low, leading to frozen pipes, flooding, or worse.

After some effort, I do find a person—an older male who won’t identify himself—who says simply: “I hate the windmills.” I follow up, and mention the name of someone I’d interviewed; the response is: “I hate him, too.” In fact, regardless of topic, every sentence he utters is prefaced “I hate...”

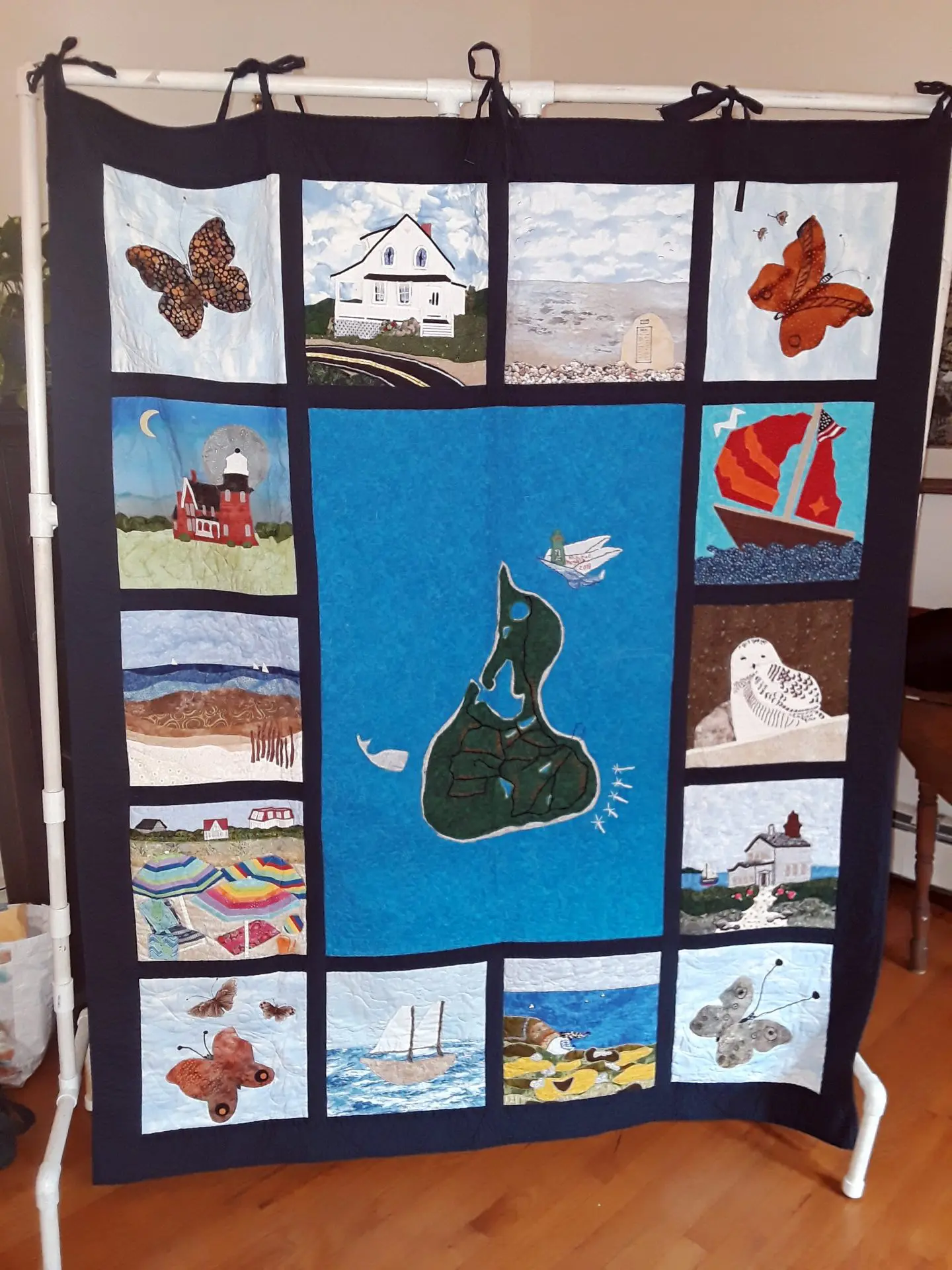

As I leave the building, the librarian shows me a photo on her iPhone of a quilt that islanders had made of Block. She did the center piece, which gives an aerial view, with a decorative element—five little white windmills—on its lower right side. Whether the quilt could be called quaint, exactly, probably depends on one’s point of view.

Editor's note: Cassius Shuman provided research assistance for this story.

Design: Thomas Gaulkin

Share:

[addthis tool="addthis_inline_share_toolbox"]