National Guard: Between protests and pandemics, no room for hurricane season?

By Rebecca Leber | June 6, 2020

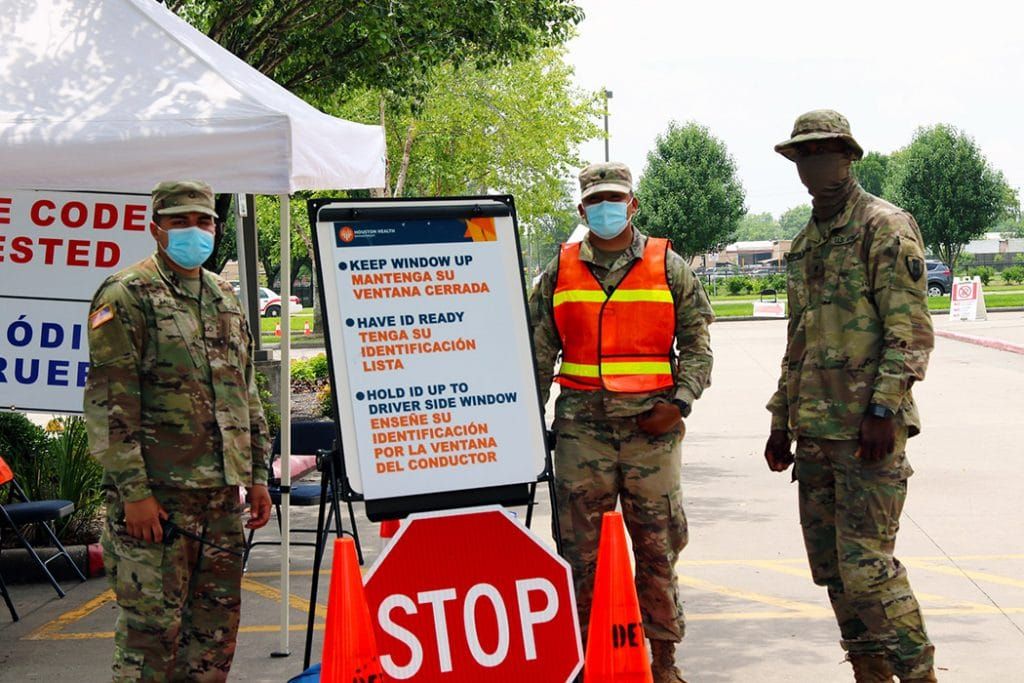

Texas Army National Guard Soldiers prepare to receive patients for COVID-19 tests at a mobile testing team facility at an elementary school, May 21, 2020. US Army National Guard photo by Sgt. Erin Castle

Texas Army National Guard Soldiers prepare to receive patients for COVID-19 tests at a mobile testing team facility at an elementary school, May 21, 2020. US Army National Guard photo by Sgt. Erin Castle

Editor’s note: This story was originally published by Mother Jones. It appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Monday marked the official calendar start of hurricane season. In the United States, we usually see the annual peak of weather disasters between summer and fall, and scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration expect this year to be especially brutal: Hotter ocean waters could fuel an especially punishing hurricane season, severe flooding in 23 states, and the record high temperatures to feed devastating wildfires.

Experts were already worried about our government’s ability to respond to a major disaster—or just as likely, many of them—in the middle of a pandemic. Now the violent crackdown on protests has added another layer to the crisis, because the National Guard typically plays a key role in the response to climate disasters, from searching and rescuing to distributing supplies, food, and medical equipment.

In the last week, 23 states and the District of Columbia have activated 17,000 National Guard members to respond to the nationwide protests calling for justice for George Floyd. That’s in addition to the 45,000 already working on the COVID-19 pandemic response, helping run drive-through testing sites and distribute supplies. That’s about 14 percent of the 450,000 National Guard soldiers and airmen across the nation. A little more context: That’s about the same number of National Guardsmen as active troops in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, and is more than the 51,000 activated in the Hurricane Katrina response.

A day after the police and National Guard troops hit demonstrators in Washington, D.C., with tear gas to clear a path for President Trump’s photo-op, I spoke with Robert Verchick, a law professor at Loyola University New Orleans and former Obama EPA official, who wrote a book on the response to Hurricane Katrina. We talked about how the multiple roles of a militarized force spells trouble for hurricane season.

Is it actually possible for the National Guard to be stretched too thin to handle climate disasters?

You’ve got tens of thousands of National Guard troops already activated because of COVID. For example, Florida has about 9,600 troops, and 2,300 of those troops are already activated because of COVID and another 700 of those troops are activated to address the protests. So you’ve got nearly a third of all of the National Guard troops already connected to something other than a national disaster. With Hurricane Irma in 2017, Florida deployed 7,700National Guardsmen. In Hurricane Katrina, we had 50,000 National Guard troops deployed and 23,000 federal troops. The numbers are huge.

If Florida’s troops are already devoted to other things, that’s fewer that can be devoted to Florida for a natural disaster. It’s fewer that could be lent to Alabama or Mississippi during a disaster. We’re just running really thin on resources, because we’ve got a triple whammy all at once.

States are using their troops already for COVID almost everywhere, and 23 states and D.C. are using troops for demonstrations now. There’s going to be a limit to how many can be moved around and what governors are going to allow for, say, Texas, Florida, and California. All have their National Guard troops activated for the demonstrations, and those are the bullseye states for extreme weather disasters.

What are you most worried about?

The National Guard’s help in disasters is one of the things that Americans have come to depend on, but there is often a tension, and the tension is that it’s a military force.

When tensions are very high and emotions are raw, you can get a situation in which either National Guard troops are acting more like law enforcers or people are perceiving them in that threatening role, whether or not they deserve that perception. That is when things can go wrong. You see in in large disaster response situations where people have been harmed or at least threatened by troops, because of misperceptions in motive. One of the things that I worry about is that when you have a situation in which you have National Guard troops who are in a caregiver-helper roles, responding to COVID emergencies, or responding to a flood or storm, and you have other National Guard troops, who are put in a state either by the governor or by the president to “maintain the peace” or suppress insurrection.

It just seems to me you’re going to have a lot of confusion about what the roles are, both confusion within the minds of the National Guard troops and confusion in the minds of people who are around them, because the public is just going to see troops in its khaki and boots. They’re not necessarily going to think, ‘Oh that’s the National Guard troops here to administer tests, and those are the ones who are going to be shooting rubber bullets.’

How was this a problem in Hurricane Katrina?

You had National Guard troops who didn’t know quite what to expect, because of blown-up, exaggerated reports about lawlessness and crime and violence and now we know almost none of that happened.

In Hurricane Katrina, we had National Guard troops in Louisiana, some of whom had just been serving in Iraq, and they would show up in what are essentially helper roles, but waving their weapons around where there are children and elderly people. It created an enormous amount of stress and an enormous amount of risk that something violent might happen that didn’t need to happen and that some kind of a mistake would be made.

During those days, President Bush famously delayed sending in federal troops for days to help in Louisiana and, at least according to some reports, the reason was he was afraid for the safety of the troops, of all things. Again, that was based on a lot of exaggerated information.

Hypothetically, imagine a state that gets a big storm. And let’s imagine this is a state with a city that has had some of these demonstrations going on. There’s a lot of amped-up press about the possibility of political protest turning violent. Then all of a sudden, there are questions about if the National Guard be sent in there to help for this storm relief. If they are sent in there, should they be armed and to what degree should they be armed? What should the rules of engagement be? It just requires an enormous amount of sensitivity and situational awareness.

Why don’t we demilitarize this response to hurricanes? Like you said, troops are supposed to be in a helping role.

It’s almost like what you hear about with good police work: What you want is to be trusted and understood by the community and communicate in a way that the community understands. How do you connect with people? Because a lot of times during a disaster organization, it’s important that people go to a certain place and stay in a sheltered secure area, but if you yell at them and wave weapons at them, that’s not the way to do it obviously.

There is a whole literature of how deescalating the display of force can help a lot in helping people during disasters. There’s a lot of evidence that shows deescalating force is good in situations involving political demonstrations. When you escalate force by police in political demonstrations, more force by police leads to more violence, not less. So it seems to me the solution to both of these problems is about tamping down displays of force and tamping down displays of aggression.

Who is in charge of the National Guard? What would it take to see these reforms?

In the case of Hurricane Katrina, you had basically three different kinds of troops. You had National Guard troops who were under the command of a governor, you had centralized National Guard troops who were under the command of the President. Then on top of that you have what you can think of as federal troop—people who are officers or soldiers under the command of a federal commander.

For instance in Hurricane Sandy, you had all three of those types of soldiers working at the same time often working together, in some cases under some kind of joint-command in which you had the federal commander commanding the state National Guard troops and the Federal National Guard troops reporting jointly to the president and to the governor.

But sometimes governors don’t trust the president, often when they’re of different parties. So during Hurricane Katrina, we had a Democratic governor who did not didn’t see eye to eye with our Republican president. And and they went back and forth as to whether or not those National Guard troops in Louisiana, and whether they should be under federal command or under state command.

It is amazingly confusing. It’s a real problem with the chain of command.

This interview was edited for clarity.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronavirus, George Floyd, National Guard, climate change, hurricane season, protests

Topics: Analysis