Two key questions about North Korea’s new missile

By Xu Tianran | October 22, 2020

In its recent military parade celebrating the 75th anniversary of the Workers’ Party of Korea, North Korea displayed a staggering 22 different weapon systems, eight of which the outside world had never seen before. These included a new type of anti-tank guided missile, a prototype battle tank, a submarine-launched ballistic missile, a short-range air defense missile system, and a new intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), to name just a few.

While North Korea’s overall steady military modernization is perhaps the most important takeaway from the parade, the new ICBM deserves special attention because of its potential strategic importance. There’s a possibility the new missile will never be much more than a mock-up. But, assuming it does eventually become operational, two crucial questions are: How vulnerable will the missile be to preemptive strikes, and what kind of payload might it carry?

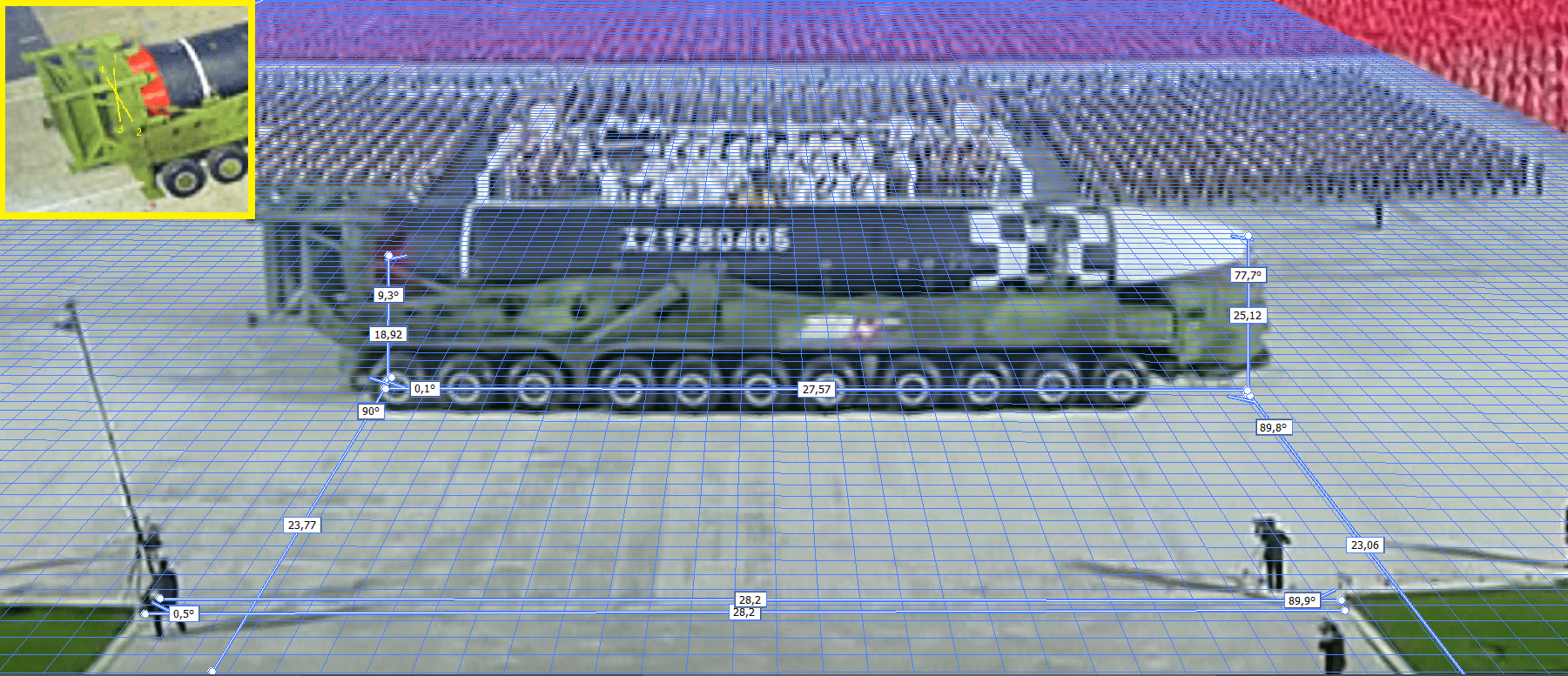

How vulnerable is it? The new missile appears to be a large, two stage, liquid propellant rocket of intercontinental range. My colleagues and I at Open Nuclear Network have estimated that it is over 25 meters long and about 2.6 meters in diameter, making it larger than the Hwasong-15, the ICBM that the country successfully tested in November 2017. While the older Hwasong-15 is estimated to be powered by one dual-chamber engine, this “new strategic weapon” is powered by a pair of such engines.

In other words, the new ICBM is not a significant breakthrough in technology, but rather an effort to achieve the biggest possible payload while maintaining a certain degree of mobility. For now, the missile has not been flight tested. But if it works, it should be able to deliver a heavy payload to anywhere in the United States.

The size has real implications for whether the missile would be vulnerable to a preemptive strike that could destroy it before launch. Of course, the missile can be transported on its 11-axle launcher, which makes it more immune than if it were stationary.

Beyond that, however, is the important question of whether the missile can be transported while fully fueled with propellant, or whether it could only be transported while empty. There are no precedents to show that such a big missile could be fueled horizontally and moved around under a combat environment on a transporter-erector-launcher (TEL).

But North Korea has previously published images that suggest the Hwasong-14, a different ICBM, could be fueled horizontally. In the Soviet Union, the 2-meter-diameter UR-100 ICBM and the 2.5-meter-diameter RS-18 ICBM, among others, were fueled in a factory and sealed in a transport launch canister, which was then moved to the silos. This does not mean the transport launch canisters had any ability to be land mobile, nor were they required to be. It simply means that transporting liquid-fueled missiles is not an outright impossibility.

If the fully fueled missile cannot be transported on a truck and erected by the hydraulic arms, it means the missile must stand on an outdoor launch pad for hours to be fueled before launch, making it very vulnerable to an adversary’s airstrike. That would mostly defeat the purpose of building and assembling such a large carrier truck.

On the other hand, if the new ICBM does have the ability to be fueled horizontally, then transported and erected, that would make it much more survivable. To make that possible, the ICBM’s structure might have been strengthened to meet such unprecedented handling requirements, presumably adding to the weight and reducing its potential performance.

Nevertheless, even if the new ICBM is more vulnerable than smaller types, that does not mean it was a wasted investment. In case the missile is never deployed, certain features could still serve as a template for future rockets. The Soviets designed but never deployed the R-26 ICBM, but its first stage propulsion system was the same that powered an intermediate range ballistic missile and a light-weight space launch vehicle. Similarly, the new North Korean missile’s first stage may very well prove useful in the future, so that the cost of designing such a big mobile ICBM could be better justified.

What is its payload? There are two possible payload options for this ICBM: multiple warheads or one large, single warhead. Both options could be accompanied by penetration aids. Although the new ICBM has a shroud—a hollow cover over the nosecone—this should not be interpreted as an indicator of the type of payload, as all North Korean ICBMs that have been flight tested have a shroud for better aerodynamic performance in the initial (“boost”) phase.

The new ICBM could probably carry around three Hwasong-15 warheads, giving it a multiple reentry vehicle or MRV payload. The introduction of a dispenser (called a “bus”) to independently direct each warhead—which would make it a multiple independent reentry vehicle, or MIRV—would eat into the payload capacity and add more complexity to the guidance system. Multiple warheads have the advantage of striking more targets or a bigger area in a single launch. They also have a higher chance of overwhelming an adversary’s missile defense system, though penetration aids could serve the same purpose.

By contrast, a large single warhead has the benefit of using less fissile material than the combined MRVs or MIRVs but offering a higher yield. Given the size of the missile, it may be capable of delivering a warhead with a megaton of explosive power. The increase in yield could be achieved by thickening the uranium 238 shell, which is inexpensive and easy to obtain.

A single warhead option also places fewer figurative eggs in one basket, an important consideration since North Korea has a weak air defense network. If the new ICBM carrying a large warhead gets taken out in an airstrike, North Korea will only lose roughly one bomb’s worth of fissile material, whereas it would lose more if it carried multiple warheads.

So, if the goal were about targeting multiple cities or defeating missile defense, several Hwasong-15s are more survivable than the same number of MRV/MIRVed warheads on a single new ICBM. What several Hwasong-15s cannot compete with, however, would be the yield of a large warhead that can only be delivered by the new ICBM.

Ultimately, North Korea’s top leadership will choose from these two payload options. On the one hand, a single megaton yield warhead would send a strong political signal because it would cross a threshold once reached by major nuclear powers. On the other hand, a MRV or MIRV payload could display technological prowess.

Every country with a missile program has to balance two competing imperatives: The need to keep the size of the rockets manageable but to maximize their destructive power. Though the outside world cannot be sure about the survivability of such a large liquid-propellant missile, it represents an effort to deliver the heaviest possible payload while maintaining at least a certain degree of mobility. If realized, this new type missile could potentially inflict much greater damage to the United States than previous North Korean ICBMs. Additionally, the new missile could also form the basis of a carrier rocket to further advance Pyongyang’s space program.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Hwasong, ICBM, Kim Jong-un, North Korea, intercontinental ballistic missile

Topics: Analysis, Nuclear Weapons