Remembering George Shultz: an interview with a key figure in ending the Cold War

By John Mecklin | February 7, 2021

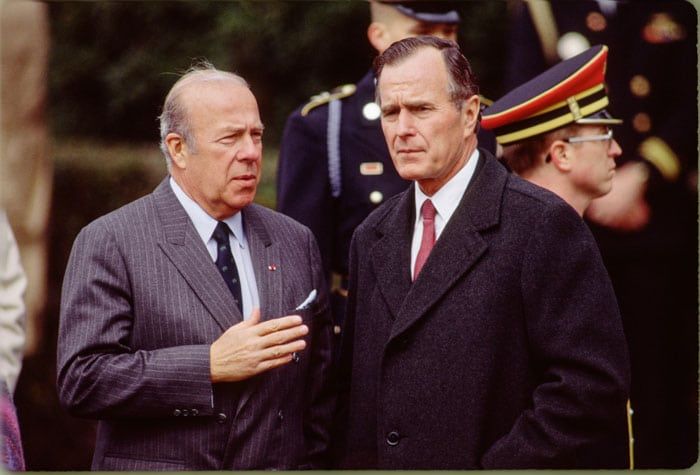

Secretary of State George P. Shultz (L) and Vice President George H.W. Bush at an event in Washington, DC, circa 1983. (Photo by David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images)

Secretary of State George P. Shultz (L) and Vice President George H.W. Bush at an event in Washington, DC, circa 1983. (Photo by David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images)

Editor’s note: Former Secretary of State George P. Shultz, one of the “four horsemen of the nuclear apocalypse” who advocated for serious moves toward less reliance on and eventual elimination of nuclear weapons, died Saturday at the age of 100. You can also read William Tobey’s remembrance of Shultz on our website here. To commemorate his decades of public service in and out of the government, we are republishing this 2013 interview, in which he details his arms control efforts and his later work in the climate change arena.

As one of President Ronald Reagan’s most trusted advisers, George P. Shultz was a key figure during the Cold War. Appointed secretary of state in 1982, Shultz was at the president’s side—often literally whispering in his ear—during the tense years when Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative, began a personal dialogue with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, and, together with Gorbachev, signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. Shultz was instrumental in mapping out the foreign policy that helped bring an end to the Cold War.

Before heading the State Department, Shultz served in the Nixon administration as secretary of labor and secretary of the treasury, and he was the first director of the Office of Management and Budget. During the Nixon years, Shultz also chaired the Council on Economic Policy. His training as an economist—first at Princeton and later at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he earned a PhD in industrial economics—prepared him well for these positions. Shultz also taught at MIT and later joined the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business.

Along with government and academia, Shultz also explored the private sector. Between his time with the Nixon and Reagan administrations, he worked for eight years as an executive at Bechtel, a large engineering and construction company. While still at Bechtel, he joined the faculty of Stanford University. After Reagan’s second term ended, Shultz returned to Stanford as a professor of international economics at the Graduate School of Business and as a distinguished fellow at the Hoover Institution, where he remains today.

In October 2006, Shultz and Hoover senior fellow Sidney D. Drell organized a conference to reconsider the vision that Reagan and Gorbachev brought to the Reykjavik summit meeting two decades earlier, where the two leaders discussed eliminating nuclear weapons but were unable to reach agreement. The Hoover conference resulted in an op-ed published in The Wall Street Journal in January 2007, authored by “the four horsemen of the nuclear apocalypse,” as they have been dubbed: Shultz; former Defense Secretary William Perry, now a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution; former Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger; and former Senator Sam Nunn, who now heads the Nuclear Threat Initiative. The influential op-ed, which called upon the United States to lead the world to “a solid consensus for reversing reliance on nuclear weapons globally,” was the first in a series advocating a nuclear-free world.

Shultz continues his work to eliminate nuclear weapons, but he has also taken up a new cause: to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. As chair of the Hoover Institution’s Shultz-Stephenson Task Force on Energy Policy, he leads a group that plans to propose a revenue-neutral tax on carbon. Shultz, who served a president known for removing solar panels from the White House, installed solar panels on his own house a few years ago and drives an electric car. The Bulletin spoke with Shultz about his new and old goals—and how he plans to reach them.

BAS: You appeared on live television immediately after “The Day After” first aired in 1983 and defended the Reagan administration’s nuclear arms buildup, but by 2007 you were calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons. When and why did your views change in those intervening 24 years?

Shultz: There’s no difference. In the earlier time, we were in a Cold War with the Soviet Union. The Soviets had deployed intermediate-range weapons to divide the Americans and the Europeans, and we were on a NATO track to either get the Soviets to agree to remove these weapons or deploy some of our own in Western Europe. The Soviets walked out of negotiations, so the NATO allies went ahead with deployments in Britain, Italy, and the most important, Germany. I believe that was a turning point in the Cold War, because it showed the Soviets that NATO was cohesive, and we could do difficult things to counter what they were doing. At the same time, Ronald Reagan had many statements on the record saying that the United States sought a world free of nuclear weapons. Reagan and I didn’t think the way to get there was just for us to eliminate nuclear weapons. We needed a process that would cause both sides to make arms reductions jointly, so our tough stance on deployments was perfectly consistent with our desire to eliminate nuclear weapons. That hasn’t changed over the years.

BAS: So the series of op-eds that you wrote with William Perry, Henry Kissinger, and Sam Nunn for The Wall Street Journal was not a change of heart?

Shultz: Ronald Reagan kept calling for a world free of nuclear weapons. I remember an address to the Japanese Diet. And we had Soviet interventions before Reykjavik. [Soviet General Secretary Konstantin] Chernenko wrote to Reagan in December 1984, basically saying, “We’ve been reading your statements, and yes, we can get to a world free of nuclear weapons.” After that, I negotiated with [Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei] Gromyko to restart the arms control negotiations. In November 1985, we had the first Reagan–Gorbachev summit, in Geneva, and one of the statements issued then was that a nuclear war can never be won and must never be fought. I think it’s important to let people know that, early in his presidency, Reagan asked the Joint Chiefs of Staff to tell him what would be the effect of an all-out Soviet nuclear attack on the United States, and they said initial casualties would be 150 million—which was about two-thirds of the US population at the time—with continuing casualties because we would have no infrastructure left. Would he retaliate? Yes. But I heard him say many times: “What’s so good about keeping the peace by an ability to wipe each other out?” The fact that we took a tough line—in the end, a successful line—in dealing with the Soviets only reinforced the objective. You don’t get to an objective by throwing away all your cards.

BAS: Do you agree with the statement made in Time magazine that your op-eds “are becoming increasingly chastened and unambitious as time goes on”? Have you given up on abolition as a near-term goal?

Shultz: I think it’s important to notice that we said, “Here is a goal, a vision, and here are the steps you have to take to get there. So let’s start taking the steps.” And since that time, a number of very positive things have happened. In September 2009, the UN Security Council had a unanimous vote in favor of a world free of nuclear weapons, and the heads of the council’s member governments made statements in support. Many referred to our work. So that’s a very positive development. Then there have been two nuclear security summits—one in Washington, one in Seoul—and the subject was how to get better control of fissile material. That’s a very important step to be taken. And it’s worth emphasizing that heads of government attended these conferences, so they were taking it very seriously. Now Iran is seeking a nuclear weapon, and North Korea has some nuclear weapons. That’s going in the wrong direction. That’s proliferation, and so we oppose the Iranian program and the North Korean program. We also know that tensions help produce nuclear weapons, as in India and Pakistan, so we have had—at the Hoover Institution—several meetings with high-ranking former officials of India and Pakistan to discuss the relationship and what can be done to improve it. We said in our op-eds that you have to do something about these regional tensions, so we’re working at it. I’m not saying we’re home free. We’re a long way from home, but we’re still working.

BAS: What is the next big step that needs to happen?

Shultz: The next thing is something that may very well come out of the fissile material meetings, and that is to construct a sense of a global enterprise. Yes, the United States and Russia have the most weapons, but most of the steps that we identified have to be taken by a broad group of countries. What we can do as private citizens—and as people at a place like Hoover and Sam Nunn’s Nuclear Threat Initiative—is to develop ideas, flesh them out, and identify people who know how to work on these things. There’s a huge difference in atmosphere between Reykjavik and now. When I came home from Reykjavik, I was virtually summoned to the British ambassador’s residence in Washington, where Margaret Thatcher “handbagged” me. You recall she had those little stiff handbags she carried? Well, the verb “handbag” in the British language means to be beaten with her handbag. She said, “George, how can you sit there and allow the president to agree to a world free of nuclear weapons?”

I thought, “Why not, he’s the president?”

“Yes, but you’re supposed to be the one with his feet on the ground.”

“But Margaret, I agree with him.”

“Grrrr…”

But when we published our essays in The Wall Street Journal, the reaction was quite different. There were—and still are—people who were avid advocates of nuclear weapons. But there was a general reaction that was much more favorable, much more willing to push forward. Now we’re reaching out for the next initiative—which, as I said, probably stems from the fissile material work—to create a joint enterprise.

BAS: At Reykjavik, where Reagan rebuffed an offer from Gorbachev to abolish nuclear weapons because it also would have restricted work on missile defense, you reportedly whispered to Reagan: “You are right.” How do you feel about that moment now?

Shultz: The president was absolutely right. The Soviets’ objective was to derail our ability to defend ourselves, and my guess is that, if we had agreed to give up on that, it would have been very hard to carry through on any agreement. It was a pointed exchange because we also talked about getting rid of ballistic missiles, and Gorbachev asked Reagan, “Mr. President, if we agree to get rid of these missiles, why do you need a defense against them?” Reagan said, “Because people know how to make them, and there will always be some rogue state around that will develop them, and then you and I will be glad that we have a way of defending ourselves.”

BAS: Do you still think that a missile defense system makes sense?

Shultz: To the extent that it is conceived of as something that can defend against one or two missiles, yes. I’m sure the Israelis right now are glad that we’ve pushed that, and they have at least a reasonable ability to defend themselves.

BAS: Is a missile-defense capability something that everyone should have and that might make it easier to abolish weapons?

Shultz: I’m certain that, if people are comfortable with eliminating weapons, they will want effective verification and effective measures to deal with any cheater. And among the measures you want is an ability to defend yourself.

BAS: You have been called the father of the Bush Doctrine. How do you feel today about the notion of “preventive war”?

Shultz: I think the idea of prevention is a no-brainer. If you see something coming at you that’s going to destroy you, you try to prevent that from happening. But implementation is hard. It’s hard enough, within the United States, to identify people who are plotting and then to nip the plot in the bud. And of course we count on international collaborative intelligence. Even way back when I was in office, there were a lot of terrorist attacks that didn’t happen because we found out about them and stopped them from happening. Every country certainly wants to do that. The issue is what a country should do when it is threatened by something going on in some other place. There the intelligence gets harder, and the questions of sovereignty come up.

BAS: You are leading a task force that is planning to propose a revenue-neutral tax on carbon to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and oil consumption. Why a tax?

Shultz: Energy affects our national security. It affects our economic health. It affects our environment—both the air we breathe and the climate that results from it. So we have to address the subject on all of these fronts, and one of the things we need to do is put all sources of energy on a level playing field. The effects on the environment are not a natural part of costs. So you need a way to make all forms of energy bear these costs, and a tax on pollution—on carbon—is a good way to do it. Doing it on a revenue-neutral basis is a good idea because then you’re not creating any fiscal drag on the economy.

BAS: Are you envisioning something similar to the revenue-neutral carbon tax in British Columbia?

Shultz: British Columbia is an interesting example. It’s a rather different case from ours, because they have huge amounts of hydropower, but nevertheless they’ve done a good job. The whole thing has been run by the Ministry of Finance. They assess the tax, they accumulate the money, and then they send back the refunds. We are trying to find out more about it. But if we were to do it in the United States, we would have to think carefully about how you impose the tax and how you make sure that people realize that it is being refunded.

BAS: When you talk about leveling the playing field, does that include eliminating subsidies for the oil and gas industry, nuclear power, and renewable energy?

Shultz: In an ideal world, it would be nice to do away with them all, but the system is shot full of them. What we need is strong and sustained support for energy research and development. Development means you take something to the point where it’s clearly operational and scalable. At that point, my opinion is that we should leave it to the marketplace and not have the government giving loan guarantees and otherwise subsidizing the commercial side of it. Subsidize R&D but not the commercial side.

BAS: Can a carbon tax succeed in the current political environment?

Shultz: Ronald Reagan always said, “If it’s a really good idea, sooner or later the American people will buy it.” And I think this is a good idea. So sooner or later, its time will come.

BAS: As president, Reagan removed solar panels from the White House roof. What made you put solar panels on your own house and start driving an electric car?

Shultz: Solar panels now are much more efficient and much less expensive than they were 25 years ago, so it makes sense. I have a little chart that I’ve shown to people that has bars representing my monthly electricity bill, before and after my solar panels. It’s a very sharp reduction. I’ve had the panels for about five years, and I’ve basically paid for them with my savings on electricity. I did it, in part, because I thought it was a good deal and, in part, because I thought, if you’re going to talk the talk, you have to walk the walk. The electric car that I drive … well, I’m driving on sunshine, and there’s plenty of it in California and it’s free.

BAS: Along with a carbon tax, your energy task force is also looking at how to deal with spent nuclear fuel internationally. What options are you considering?

Shultz: In our work on a nuclear-free world, we say that among the steps needed is to get control of the nuclear fuel cycle, and I think some sort of international method is the right way. Sam Nunn’s group, the Nuclear Threat Initiative, has made a lot of progress toward a fuel bank, which is a way of assuring countries that they can have access to enriched uranium for a power plant without doing it themselves.

BAS: You co-edited, with Sidney D. Drell, The Nuclear Enterprise—a book on how to improve safety for nuclear reactors as well as for nuclear weapons. If nuclear power plants pose catastrophic risks, why aren’t you calling for their abolition, too?

Shultz: Well, I think we have a very good safety record in the United States on nuclear power. It’s just astonishingly good. And the methods of keeping it that way are in place, so what we advocate is a very high safety culture in everything connected with the nuclear enterprise, because you’re dealing with something where the probability of an event is very low but the consequences are huge. So it has to be a gigantic safety effort everywhere, and that’s not only in the United States but globally.

BAS: How do you feel about the political polarization that we see today on climate change and other environmental issues? What hope, if any, do you hold out for bipartisan consensus of the sort that was common during the Nixon days?

Shultz: I think the facts will wind up being compelling. I remember when, in the Reagan administration, we found that the ozone layer was in danger of depleting. Most scientists thought it was happening; some questioned it, but they all agreed that, if it happened, it would be catastrophic. I talked with President Reagan a lot about it, and I said, “We should take out an insurance policy,” and the Montreal Protocol came about as a result of that. Sometimes when a clear and desirable objective takes hold, people come up with ideas of how to achieve it—and DuPont did that, so we were able to get an agreement internationally. It turned out that the scientists who were worried were right, and we acted in the nick of time. Now, on the global warming issue, I think by this time it’s pretty obvious that the planet is warming. After all, there’s a new ocean being created, and we’re having big diplomatic issues around access to minerals and navigation rights and what’s going to happen to the native populations in the Arctic. That’s not an opinion; it’s an observable reality. We need to figure out what to do about it as best we can.

BAS: The Kyoto Protocol on climate change, which seems similar in some respects to the Montreal Protocol on ozone depletion, was a failure. Why?

Shultz: It wasn’t similar. The people who negotiated the Kyoto Protocol on our behalf did not properly represent the United States. For the Montreal Protocol, we consulted with the Senate. They knew what we were doing. We got their views. And when it was time to ratify the treaty, it was easy. In the Kyoto case, the Senate voted 95 to nothing that the negotiators should not bring back to the Senate the treaty that was under consideration, because it did nothing about the activities of China and India and other developing countries. So they brought back a treaty that was defective, and it never went anywhere. That was the fault of the negotiators. They didn’t strike a good enough deal.

BAS: Do you see potential for a do-over?

Shultz: I think the way they’re going about it now is not likely to get results. What you have to do, at least in my experience on these things, is get the key countries together and bring about a consensus that “yes, we have a problem that affects us all, and there are things we can do about it.” Let’s identify the things that can be done and encourage research on that. So we’re not just talking about objectives, we’re talking about things to do. Once key countries sign on, others will. And in the case of the very poor countries, the industrialized countries can do as they did in the Montreal Protocol: They provided a fund to help developing countries get started. So I think that’s the way to go about it—a much more pragmatic method.

BAS: Many experts see parallels between climate change and nuclear weapons: Both are threats that often seem remote from our day-to-day lives yet have the potential to radically alter our world. What lessons have you learned from your work on nuclear weapons reduction that might help with the push to reduce carbon emissions?

Shultz: I haven’t really tried to put those issues together; they’re rather different. But I do recommend what we have advocated in the nuclear weapons field: Set out a vision. Without a vision, the steps that you identify don’t seem fair. Without the steps, the vision seems unrealistic. So you combine vision with doable steps that you can identify and get your arms around.

George Shultz spoke during the Bulletin’s 2016 Doomsday Clock announcement, which was hosted in partnership with the Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC) at Stanford University (from The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists on Vimeo).

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: George Shultz, Interview, four horsemen of the nuclear apocalypse, obituary

Topics: Climate Change, Nuclear Weapons