Israeli public opinion makes a US-Iran nuclear deal urgent

By Doreen Horschig | May 14, 2021

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Credit: Israeli Government Press Office/Kobi Gideon

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Credit: Israeli Government Press Office/Kobi Gideon

Israel has consistently opposed the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—the 2015 Iran nuclear deal that the Biden administration is seeking to revive. The recent diplomatic talks in Vienna have been a welcome opportunity for proponents of the deal. But when progress was reported, Israel allegedly damaged an Iranian military vessel and a few days later caused a power outage at the Iranian nuclear site in Natanz.

Israel believes Tehran never abandoned its ambition to become a nuclear-armed state and that the deal paves the path for realizing this ambition. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his administration have been trying to convince the United States that a return to the JCPOA would be a mistake unless major flaws are addressed.

There are some straightforward reasons why it might be in Israel’s interest to revive the JCPOA, including a reduction of Iran’s installed centrifuges and stockpiles of enriched uranium. But another reason for reviving the deal has received little attention: Israeli public opinion. Not because the public supports the JCPOA (they don’t), but because—as my own recent research found—the Israeli public is highly hawkish and would be supportive of a nuclear first strike against a nuclear-armed Iran.

In other words, the world cannot rely on the Israeli public to avoid atomic warfare in the Middle East. Because of this, the Biden administration needs to redouble its efforts to make sure that the United States and Iran re-enter the nuclear deal. If Iran further develops the bomb and eventually obtains it, Israel’s government has public backing for a nuclear first strike against Iran—which would be both a regional and global disaster. The Israeli public will not provide a constraint if a nuclear strike is being considered.

Israel and Iran’s nuclear program. When the Trump administration withdrew from the JCPOA in 2018 and imposed crippling economic sanctions, Iran responded by increasing its uranium enrichment and building new, advanced centrifuges. Iran has since abandoned all limits on its uranium stockpile—limits that it had fully complied with before US withdrawal.

Even though the consequences were fairly predictable, Netanyahu applauded President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw from the deal and has largely criticized any efforts to revive it under the Biden administration.

Israel has expressed three major concerns about the agreement, echoing the Trump administration’s reasons for withdrawal. First, Israel questions the sunset clauses of the agreement (“termination day” is currently set to October 2025) and argues that Iran could resume its pursuit of nuclear weapons if the agreement is not renewed. Second, Israel is concerned that the JCPOA puts no limits on Iran’s ballistic missile program. Iran currently limits the range of its ballistic missiles to 2,000 kilometers, but that is only a voluntary measure. Third, the Israeli government repeatedly questions the ability of the JCPOA verification regime—led by the International Atomic Energy Agency—to fully inspect undeclared research sites and activities.

But if the deal is not revived, the likelihood of Israel’s concerns becoming reality is just as high (if not higher). None of these concerns were successfully addressed by the US withdrawal. Instead, withdrawal effectively moved the sunset clauses forward to the present day.

Israel has been trying to use counterproliferation efforts to address its concerns. On several occasions Israel disrupted, set back, and undermined aspects of Iran’s nuclear program. In 2010 an Israeli-US computer worm, called Stuxnet, sabotaged Iranian gas centrifuges. Israel also was allegedly involved in assassinations of Iranian nuclear scientists and explosions at nuclear facilities. Most recently, the explosion that caused a power outage at Natanz might have set back part of Iran’s nuclear program by at least nine months.

Israel’s position is that a nuclear Iran would pose an existential threat. However, there is little tangible evidence that covert methods have had long-term effects constraining Iran’s nuclear program. On the contrary, the most recent action prompted Iran to increase uranium enrichment up to 60 percent purity (90 percent is suitable for a nuclear weapon). Similarly, Iran moved to increase uranium enrichment in response to the assassination of its top nuclear scientist, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh. Hardening Iran’s resolve to potentially reconstitute its nuclear weapons program seems like a questionable trade-off unless Israel is confident that it can keep sabotaging the program indefinitely—and effectively enough to prevent Iran from developing a warhead.

Israeli public opinion. Very few recent polls have attempted to identify preferences among the Israeli population for a nuclear strike. To fill this gap, I worked with Midgam—an Israeli research and consulting firm that frequently partners with academics—last summer to survey a nationally representative sample of 1,022 Israeli adults, including both Jews and Arabs. The survey aims to understand the circumstances under which people might support a first strike with a nuclear weapon.

In 2017, the Bulletin published an article highlighting a landmark experimental study by scholars Scott Sagan and Benjamin Valentino. In the study, the authors found that a clear majority of Americans would approve of a nuclear attack on Iran that would kill 2 million civilians. In contrast to regular polls, respondents were presented with a fictional news article that provided a trade-off between risking US soldiers’ lives and killing foreign Iranian noncombatants. Follow-on research by Janina Dill, Sagan, and Valentino compared US, British, French, and Israeli public opinion about using nuclear weapons, and found that the Israeli respondents displayed the most hawkish preferences.

My survey results confirm a large hawkish majority indeed lurks within the Israeli public. Survey respondents read a government press release presenting a scenario that included an Iranian nuclear threat—and suggesting that an Israeli nuclear strike would effectively destroy an Iranian nuclear facility. The respondents were then asked: “Given the facts described in the article, if Israel decides to strike, how much would you approve or disapprove of this decision?” The findings suggest that 60 percent of Israelis approved of a nuclear first strike on Natanz if they felt threatened by a (hypothetically) nuclear-armed Iran. Even with a reminder of likely Iranian retaliation, approval for a strike was higher (45 percent) than disapproval (38 percent).

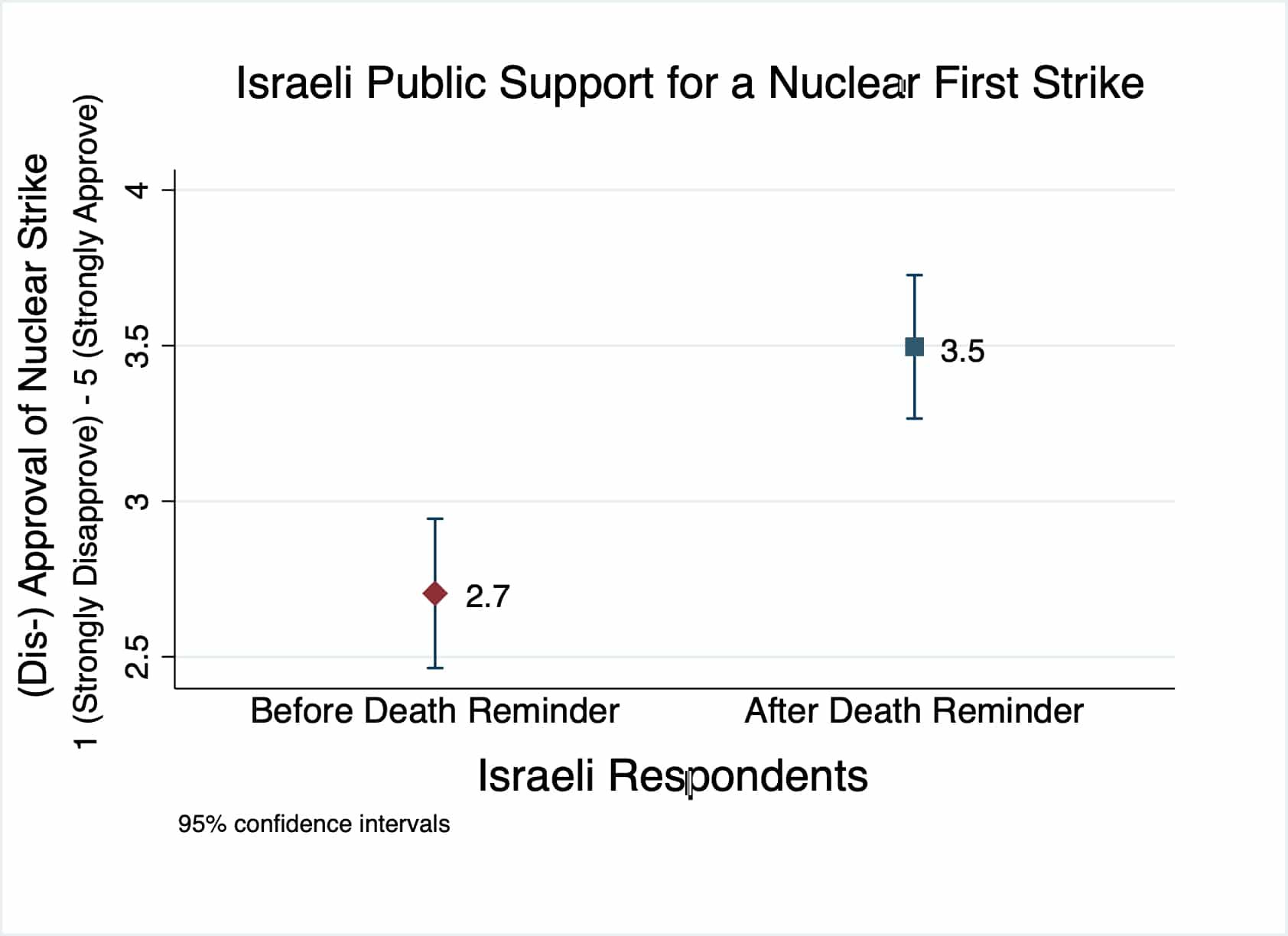

When I dug deeper to explore why some people are so supportive of the use of an atomic bomb, my research suggested that Israelis who were reminded of their mortality (through open-ended questions about their own deaths) were significantly more likely to support nuclear use in a first strike than those who were not reminded of death. Though it may seem paradoxical, a theory of psychology called Terror Management Theory predicts just that. It suggests that, when individuals are prompted to think of their own death, they become less risk-averse and increase their support for extreme aggression toward whatever it is that challenges their worldview—a worldview that normally provides a defensive death-denying belief. And what could remind Israelis more of their death than the threat of a nuclear-armed Iran?

This all suggests that the public cannot be counted on to be a constraint on Israeli leadership. Unlike during the Cold War, when people took to the streets to protest the US-Soviet arms race and use of nuclear weapons, there is currently no visible pro-disarmament sentiment in Israel. No public opposition in Israel will put a check on an Israeli nuclear first strike.

To avoid a dire conflict, it is in Israel’s interest to support diplomatic steps. So far, the JCPOA has prevented a trajectory to a nuclear first strike more effectively than counterproliferation measures and withdrawal did. If Israel needs one more reason to sympathize with the JCPOA, here it is: Public hawkishness could be a contributing factor that spirals the country into a nuclear crisis.

Netanyahu has made numerous provocative statements, including: “Those who threaten us with annihilation put themselves in mortal peril. Israel will defend itself with the full force of our arms and the full power of our convictions.” Opposing the nuclear deal serves his short-term electoral goals and caters to his political base that opposes the deal. But it is a dangerous game in the long term, as it raises the stakes with Iran and could backfire.

If the continued existence of the Israeli state is Netanyahu’s primary goal, then getting into a nuclear confrontation with Iran amid public calls for war is probably not the best way to accomplish that. Both sides are going to lose in an Israel-Iran nuclear war.

Preventing a nuclear crisis. Albeit imperfect, the JCPOA had been working before the US withdrawal. Iran stopped taking steps to develop warheads. In fact, the deal did far more to constrain Iran’s nuclear program than the cyberattacks, assassinations, and sabotage.

If Israel wants to prevent a situation in which a nuclear-armed Iran causes the Israeli citizenry to support a nuclear first strike, then it should get on board with the JCPOA. And the Israeli public’s hawkishness should give the Biden administration an increased sense of purpose and urgency.

The window of opportunity to revive the Iran nuclear deal is closing quickly. At the moment, the negotiations in Vienna are progressing. But Iran and the United States need to come to terms, and the sooner the better. The Biden administration is occupied with many items on its national security agenda, Iran is preparing for national elections in June, and hardliners are making their voices heard. Now is the time to listen to proponents of the deal and show support for the agreement and a way back into compliance for Iran and the United States.

While the deal is not perfect, it’s at least a measure that has shown effectiveness in the past. The majority of experts who study the Middle East (75 percent) believe that a US return to the JCPOA would make it less likely that Iran gets a nuclear weapon in the next 10 years. No one can know with certainty that the deal prevents a nuclear Iran, but a renewal can be used as a basis for follow-on negotiations that could address the very things the Israeli government is concerned about, such as ballistic missiles and various malign activities. There is no way to get there without reentry into the deal.

Editor’s note: This article builds on the academic manuscript “Israeli Public Opinion on the Use of Nuclear Weapons: Lessons from Terror Management Theory.” Data and results from the study are available from the author upon request. The author thanks John Carl Baker, Tom Collina, Rebecca Davis Gibbons, John Krzyzaniak, Heather Williams, and CSIS PONI Nuclear Scholars for their invaluable comments and feedback on drafts of this article. The views and any remaining errors in this article are those of the author alone. The author is the Roger Hale Fellow at the Ploughshares Fund, which provides financial support to the Bulletin.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Iran, Israel, JCPOA

Topics: Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons, Voices of Tomorrow