Nuclear power won’t fix Iraq’s energy crisis

By Nils Holst | August 18, 2021

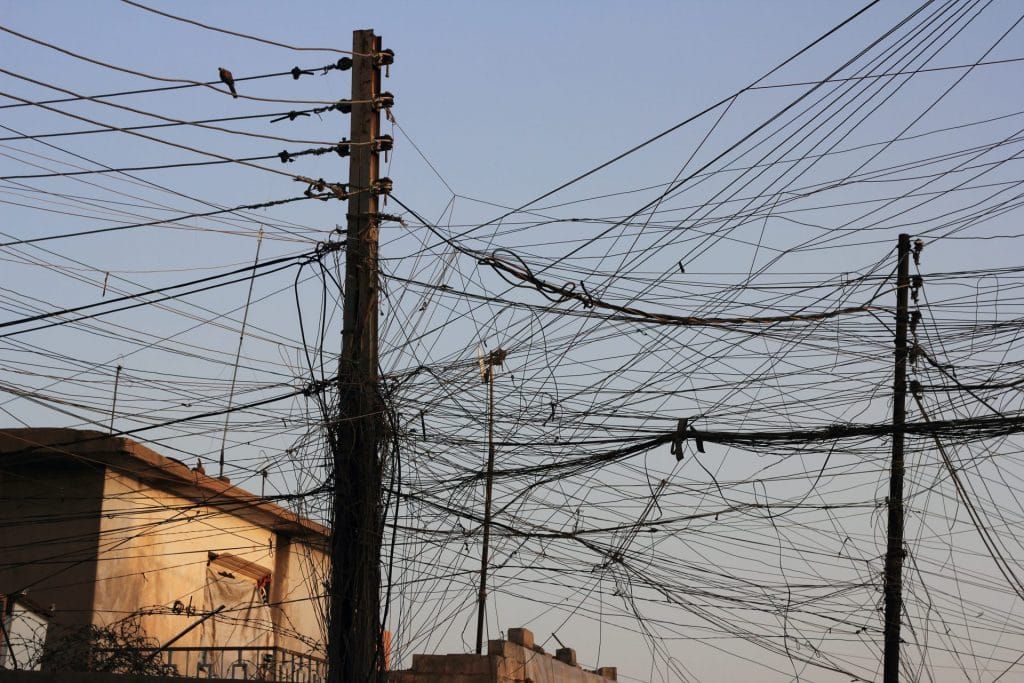

A tangle of power lines in Erbil, the most populated city in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Credit: Leif Hinrichsen/Creative Commons

A tangle of power lines in Erbil, the most populated city in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Credit: Leif Hinrichsen/Creative Commons

On June 29, Iran halted gas and electricity exports to Iraq over nonpayment of fees. The move left millions of Iraqis without power as temperatures soared to more than 120 degrees, turning cities into ovens and throwing the embattled government of Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi into yet another political firestorm. While the Iranian move was clearly designed to increase Tehran’s influence over its neighbor, it also raises questions about Iraq’s proposal last month to restart the country’s civilian nuclear program, once the subject of proliferation concern.

Iraq is the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries’ second-largest producer and has some of the largest oil and natural gas reserves on the planet. By rights Iraq should be energy self-sufficient, but decades of war damage and mismanagement, combined with an overreliance on oil and gas exports, mean the country doesn’t generate enough power to meet demand. Instead, between a quarter and a third of Iraq’s electricity is produced with piped-in Iranian gas, and Iraq also imports about 5 percent of its electricity directly from Iran—an uncomfortable reliance on a historic enemy.

The Iraqi government owed Iran $4 billion in unpaid utility bills at the end of June, but the coronavirus pandemic and other economic troubles have made it difficult to pay. What money Iraq does release must perform complex financial acrobatics to get around US sanctions on Iran, a process Iran says takes too long.

Against this backdrop, Iraq’s announcement that it plans to spend $40 billion on eight nuclear reactors for civilian energy production is puzzling. Nuclear power would diversify the country’s energy sources and make the petrostate less dependent on energy imports from its neighbors, but there are faster and cheaper ways to help the millions of Iraqis currently without power in the sweltering heat.

Iraq’s nuclear legacy. Iraq received its first research reactor from the Soviet Union in 1962, and acquired several more over the next two decades. Although these reactors were purportedly developed for peaceful purposes, Iraq launched a covert nuclear weapons program in the early 1970s in violation of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which it signed in 1968. Concerned with Iraq’s likely nuclear weapons development, Israel bombed the Osiraq reactor complex in 1981, driving Iraq’s nuclear weapons program underground. Iraq spent the next decade experimenting with different methods to enrich uranium covertly to weapons-grade levels (typically 90 percent uranium 235), along with additional research on nuclear weapons designs.

After the 1991 Gulf War, the United Nations Security Council instructed the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to dismantle Iraq’s nuclear weapons program. The IAEA removed all weapons-grade nuclear material from Iraq and destroyed or disabled the country’s nuclear facilities. Iraq was reluctant to cooperate with international inspectors, however, which, coupled with then-President Saddam Hussein’s tendency to exaggerate his country’s weapons-of-mass-destruction capabilities, led US intelligence agencies to incorrectly assess that Iraq was hiding a nuclear weapons program. This assessment led to the 2003 US invasion, after which it was discovered that Hussein had not, in fact, restarted the program.

The Iraqi government made efforts to conform to international nonproliferation norms in the post-Hussein era. Iraq ratified the IAEA Additional Protocol in 2012, giving the IAEA greater insight into the country’s nuclear activities, and the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 2013. The UN Security Council lifted restrictions on Iraq’s nuclear industry in 2010. Current and former government officials have routinely floated the idea of using nuclear power to solve the country’s crippling energy shortages, which leave large parts of the country without power during the hot summer months, a major cause of political unrest in recent years.

In June, Kamal Hussein Latif, chairman of the Iraqi Radioactive Sources Regulatory Authority, said the Iraqi government is currently in talks with Russia’s Rosatom about a $40 billion plan to build eight nuclear reactors. Latif also said Iraq discussed the plan with French, American and South Korean officials. Rosatom has secured contracts to construct nuclear reactors with several of Iraq’s neighbors, including Turkey, Iran, Jordan, and Egypt, although the contract with Jordan later fell through.

The $40 billion question. Part of Iraq’s nation-building strategy is ensuring greater access to electricity, and Baghdad sees nuclear power as an attractive way to address this challenge. The proposed eight-reactor plan would provide the country with a steady 11 gigawatts of power, bridging the gap between supply and demand even during the hottest part of the year. Iraq would reduce its reliance on Iranian gas, free up more of its hydrocarbons for export, and limit its dependence on carbon-based fuel generally. Nuclear power could also boost the legitimacy of al-Kadhimi’s government, and potentially rehabilitate Iraq’s image as an upstanding member of the civilian nuclear community.

There are some problems with this plan, though. Establishing and maintaining nuclear facilities would impose a large financial burden on a government already struggling to provide basic services to its citizens. Declining oil prices in 2020 forced Iraq to dip into its foreign reserves to pay public-sector salaries, and to shelve a much smaller plan to repair and upgrade the country’s dilapidated transmission and distribution network. And don’t forget the $4 billion Iraq owes Iran in unpaid utility bills, the cause of the most recent blackouts sweeping the country. Even with favorable terms, a $40 billion project would be hard to justify given the government’s difficulty meeting its current financial obligations.

Compounding the affordability problem is the fact that about two thirds of generated power isn’t paid for, due to theft or unmetered connections. The government already heavily subsidizes electricity costs, with customers only paying for about 10 percent of the actual cost of the electricity they use. As a result, the Ministry of Electricity needs $12 billion per year to balance the books. Adding nuclear energy to the mix would push the ministry even deeper into the red, depending on how much financing Iraq could get for the project.

Proliferation is another major concern. The Iraqi power grid has weathered 35 terror attacks so far this year. Introducing nuclear technology would increase the risk of nuclear material falling into terrorist hands, either through a direct attack on a nuclear facility or via a corrupt government official. Given the country’s existing abundant energy resources, Iraq’s neighbors may suspect a civilian nuclear program is once again a cover story for weapons development. With other regional states like Turkey and Saudi Arabia toying with the idea of nuclear weapons, the appearance of seemingly unaffordable reactors in Iraq could be the straw that breaks the back of the already overburdened camel that is nonproliferation in the Middle East. Uncertainty over what happens if the Iran nuclear deal is not renewed, or renewed but expires in a few years, adds to this danger.

Iraq needs energy, but nuclear power is not the answer. In the short term, Iraq must rebuild its broken transmission and distribution system, overhaul the Ministry of Electricity’s fee collection system, and remove bottlenecks in the gas pipeline network to improve generation capacity. In the medium term, the country can encourage renewable energy use and diversify its energy mix by expanding solar power projects and refurbishing existing hydroelectric facilities. These infrastructure projects will ensure Iraq has reliable and consistent power generation in the long term, and be a better use of resources than an unnecessary, budget-busting prestige project.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Iran, Iraq

Topics: Nuclear Energy, Nuclear Risk, Voices of Tomorrow

Would be nice if the Bulletin could also mention improving energy efficiency. That can be done by each and every user – and it will reduce the impact of shortages. Shading buildings, use of cool colors, appropriate ventilation, planting trees, …. it all can work and will reduce the impact of crises by reducing the demand in normal operation. And it will reduce climate change problems.