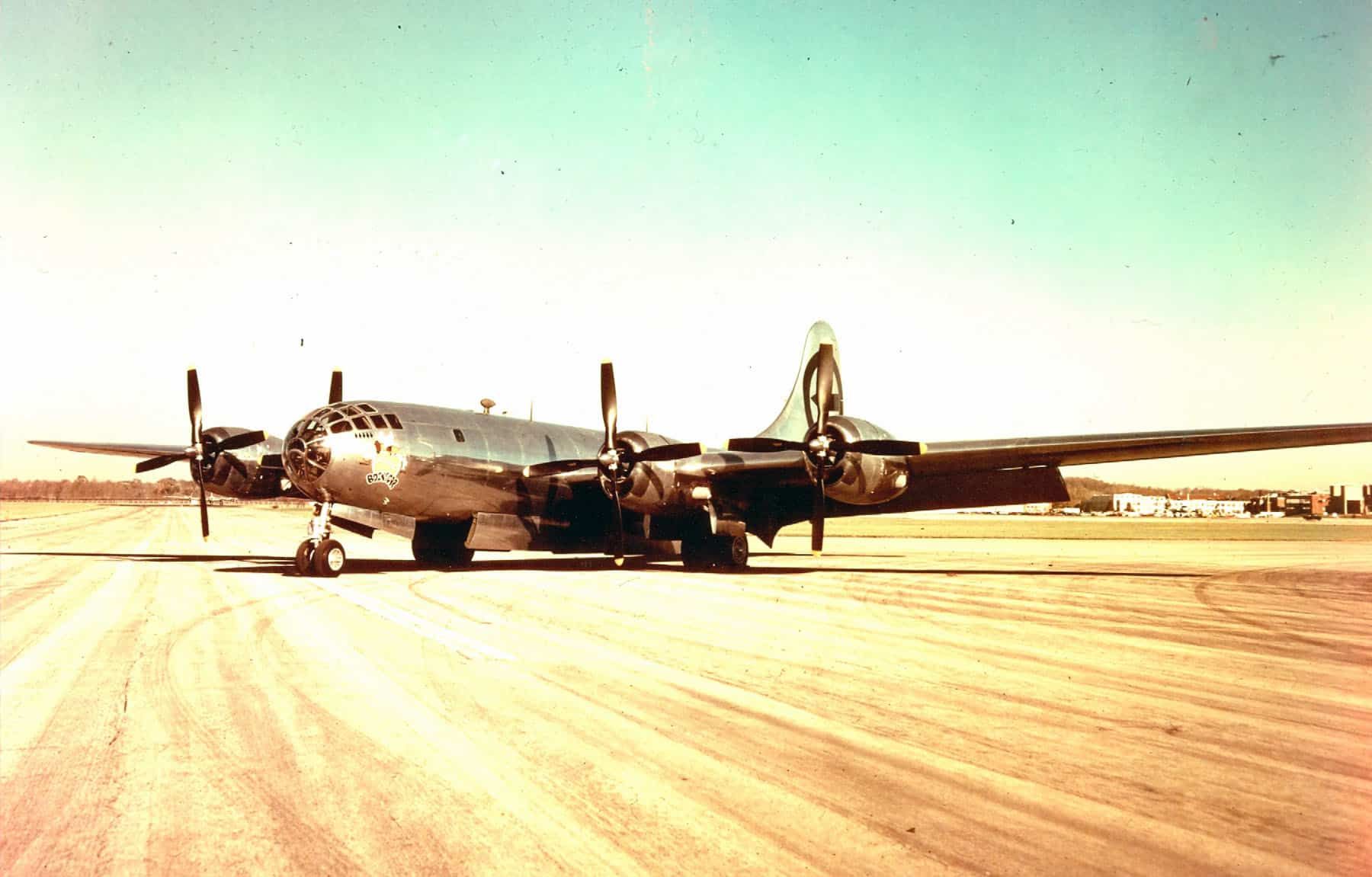

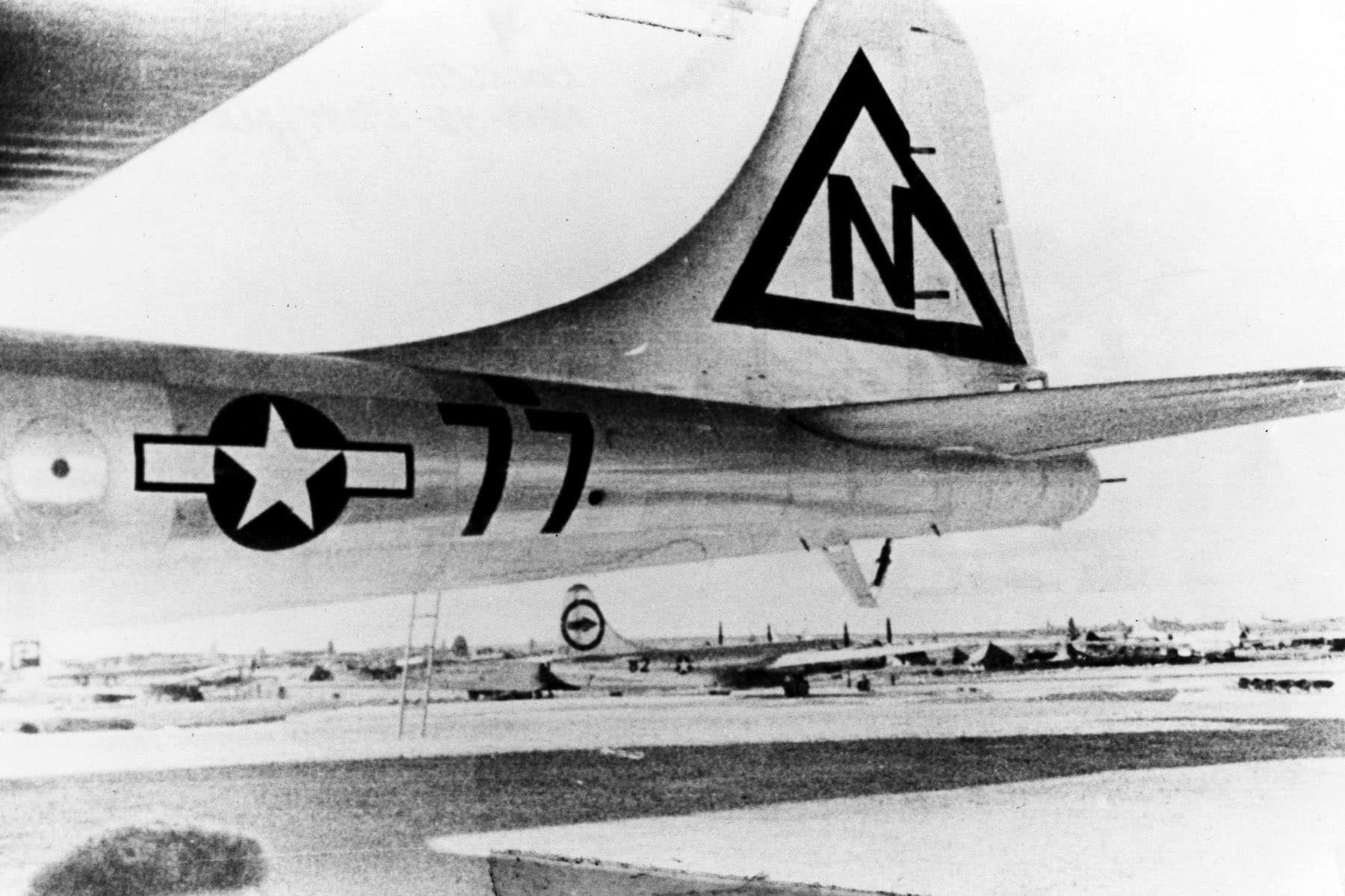

"Bockscar" en route to Japan with the atomic bomb on board, August 9, 1945. (US Air Force photo)

The harrowing story of the Nagasaki bombing mission

By Ellen Bradbury, Sandra Blakeslee Originally published August 4, 2015

The harrowing story of the Nagasaki bombing mission

By Ellen Bradbury, Sandra Blakeslee

Originally published August 4, 2015

Editor’s note: Due to popular demand we thought it appropriate to republish this Bulletin article, which deals with an often-overlooked aspect of the atomic bombings in Japan, as told to New York Times reporter Sandra Blakeslee by Ellen Bradbury of Los Alamos.

First, some background. Before he died in 2005, retired Navy man Frederick L. Ashworth revealed some little-known information about the dropping of the Nagasaki atomic bomb to his friend and neighbor, Ellen Bradbury, who subsequently wrote it down. Ashworth had been the operations officer in charge of the final testing and assembly of the “Fat Man” atomic bomb components, and he was in command of the device while aboard the plane that actually dropped the weapon on Nagasaki. Years later, New York Times science reporter Sandra Blakeslee worked closely with Bradbury to craft the article below from Ashworth’s recollections, and to locate corroborating accounts, interviews, and other support materials. Other observers may disagree with Ashworth’s details and views—especially because so much time has passed since August 9, 1945. But Ashworth’s detailed, in-depth account—recounted here in full for the first time—provides a different view of the Nagasaki mission than much of what was written previously.

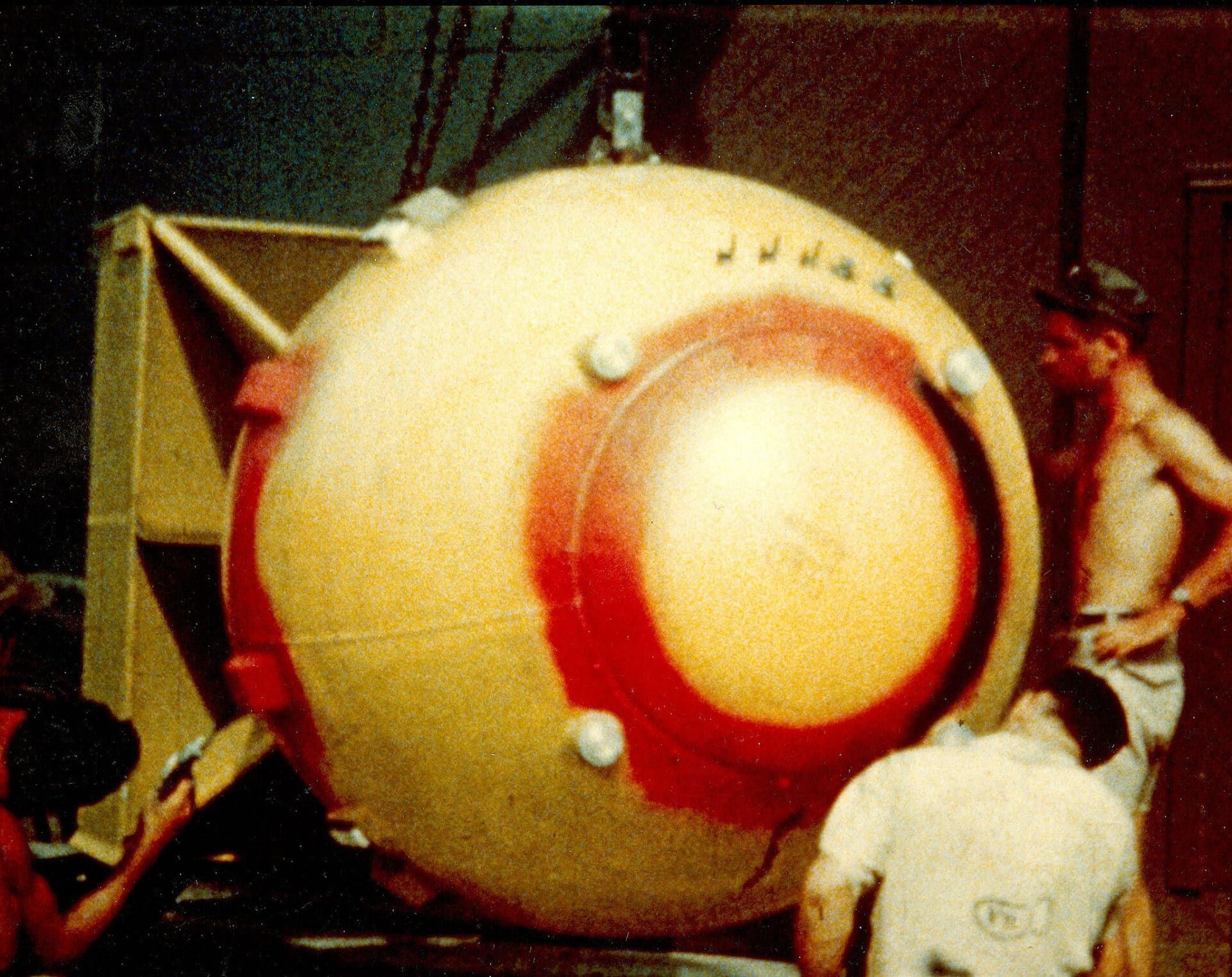

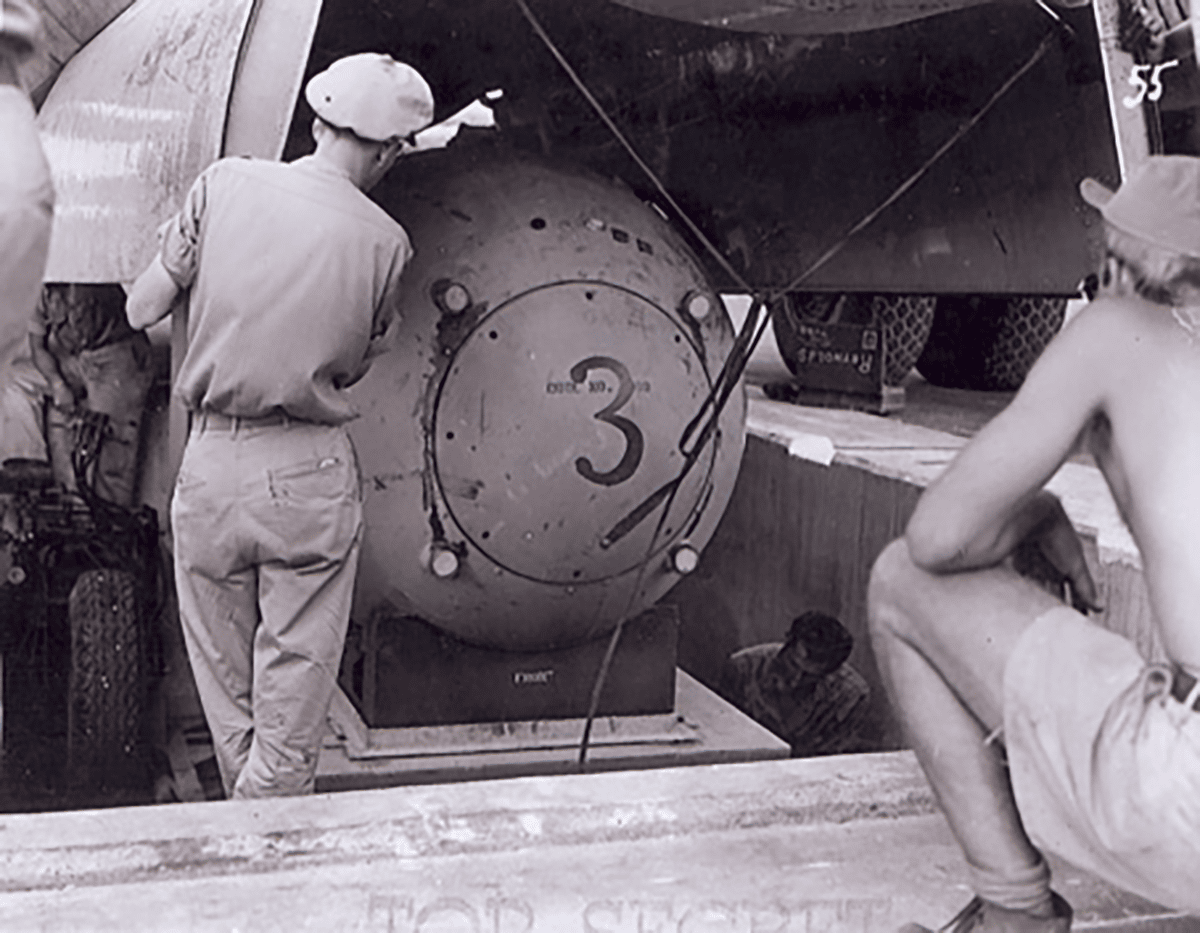

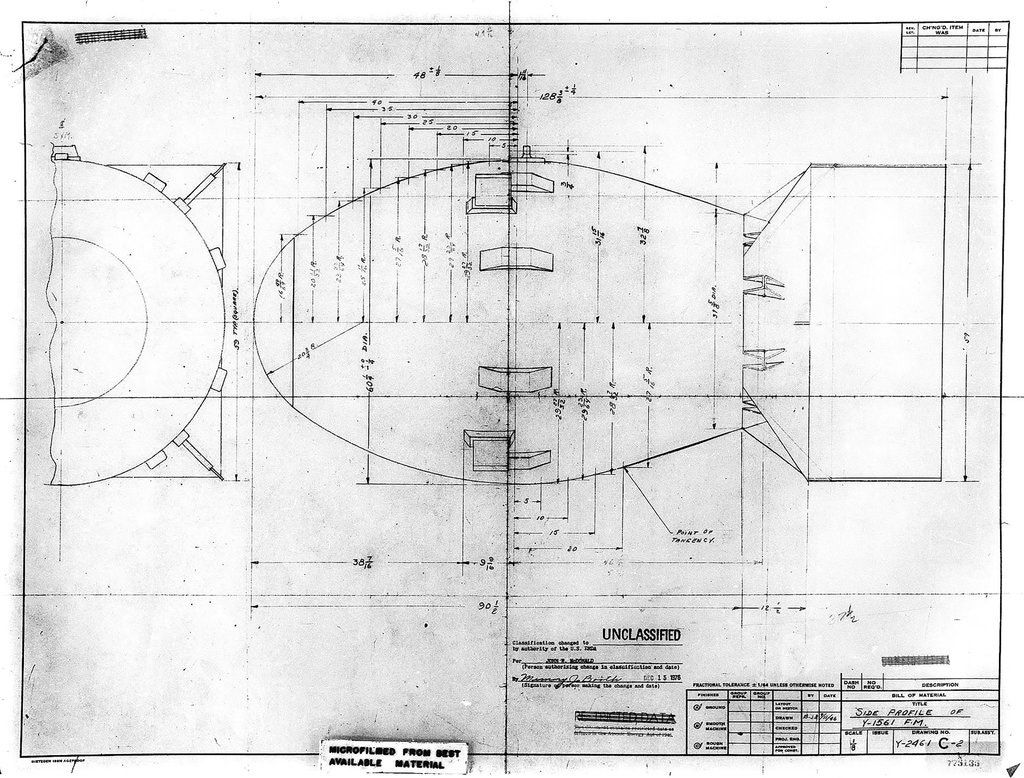

Seventy years ago, on August 9, at approximately 3:47 a.m. local time on the island of Tinian, a massive B-29 Superfortress aircraft roared down a tropical airport runway, carrying 13 men and what was then the world’s most destructive weapon—an atomic bomb called Fat Man. It was the second atomic bomb in existence (not counting the test in the New Mexico desert about 3 weeks earlier). And it was far more powerful than the first atomic bomb to be used in warfare, which was called “Little Boy” and had been dropped on Hiroshima just three days earlier.

For nearly eight hours, the crew of the plane carrying Fat Man sped toward mainland Japan, each man hunkered in a cramped workspace with no access to external radio communication. Outside, monsoon winds, rain, and lightning lashed at them. Inside, they experienced moments of terror, such as when the bomb began to arm itself—a red light blinking with increasing rapidity—midway to their destination. One of them, bearing the newly minted title “weaponeer,” grabbed the Bomb’s blueprints and raced to figure out what was wrong.

The story of what transpired inside the plane carrying Fat Man to Nagasaki, Japan, has not really been told in detail to this extent, although some excellent overall renditions have been written of the atomic bomb program as a whole. Bits and pieces of the story have appeared in the diaries of the men who flew the mission—although sometimes the diaries appeared years after the event, or were based on hurriedly scribbled, hand-written notes jotted down during the flight. Scrubbed versions have been published in military archives. A couple of accounts differ, suggesting false memories or outright lies, making the whole tale reminiscent of the famous Japanese film Rashomon.

It is a story of astonishing screw-ups that easily could have plunged the plane, the men, and the bomb into the Pacific Ocean. That the mission succeeded is genuinely miraculous. New, in-depth particulars of what went wrong, recounted here in a single narrative for what may be the first time, matter a great deal.

RELATED POSTS

Fat Man versus Little Boy. The Little Boy bomb dropped on Hiroshima continues to garner the most publicity, because it was the first-ever atomic weapon to be used in an attack. But compared to the Fat Man implosion assembly design, Little Boy’s output was puny, even though “little” is hardly the adjective that springs to mind for a bomb that was 10 feet long, 28 inches wide, and weighed 9,000 pounds. Despite its size, Little Boy was “crude,” wrote physicist Frank Barnaby of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute more than three decades later; a modern 8-inch nuclear artillery shell has about the same yield as the first atomic bomb. The Little Boy design was never built or used again.

Fat Man became the basis for US domination in the nuclear age. Its design became the model for all atom bombs that followed—including the kinds of things that North Korea and all new atomic powers seek to accomplish today, according to William J. Broad, science reporter for the New York Times. An implosion bomb that used plutonium, Fat Man produced far more bang for the buck: the explosive power of 22 kilotons of TNT from Fat Man, versus the 12.5 kilotons of Little Boy.

There is another difference as well: Fat Man almost didn’t reach its target. Unlike the Hiroshima mission, which was nearly flawless, almost nothing during the Nagasaki mission went according to plan, atomic historians say. Its failure might have changed the course of history, discrediting the utility of this new bomb design and possibly affecting the course of subsequent nuclear weapons use. The mission was a game changer, yet the military has been loathe to talk about it for reasons of national security and, perhaps, embarrassment.

I learned harrowing new details of this historic flight from the weaponeer, Vice Admiral Frederick Lincoln “Dick” Ashworth, a few months before he died in 2005, in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Ashworth had been a Navy commander who helped to select Tinian as the base for the atomic mission. He then became the operations officer in charge of the final testing and assembly of the bomb components on the island and was ultimately the person in charge of the atomic bomb while aboard the plane that dropped the bomb on Nagasaki.

And he was my neighbor. I grew up in Los Alamos, where my father had been hired by Norris Bradbury to work on the implosion detonator for the Fat Man bomb. Which is partly why, I think, Ashworth opened up to me. (Full disclosure: Los Alamos in those days was a small, tight-knit community, much more so than today. Back then, it seemed that everyone knew everyone else. And Norris Bradbury was to eventually become my father-in-law.) Maybe it was because of these facts that Ashworth—normally a buttoned-up kind of guy, averse to any whiff of disloyalty—spoke candidly about the conflicts that occurred before the bomb was dropped. Luckily, I wrote down his recollections and saved all his emails. He stressed that he didn’t have the energy, time, or inclination to tell the story in “a big way” to national media. (Although Ashworth did give an account to the Los Alamos Historical Society, which is still in the process of digitizing its recordings.)

While it may not be found in official histories, what Ashworth had to say contains the ring of truth. A leading civilian expert on the bombing missions, John Coster-Mullen—whose self-published research is considered by prominent atomic historians such as Robert Norris to be the ultimate authority on what happened—corroborated Ashworth’s version. (In his review of Coster-Mullen’s book Atom Bombs: The Top Secret Inside Story of Little Boy and Fat Man, Norris said: “Nothing else in the Manhattan Project literature comes close to his exacting breakdown of the bomb’s parts. Coster-Mullen describes the size, weight, and composition of many of Little Boy’s components, including the nose section and its target case; the uranium-235 target rings and tamper; the arming and fuzing system; the forged steel 6.5-inch-in-diameter gun barrel through which the uranium-235 projectile was fired at the target rings; and the tail section—to cite just a few.”)

And what does Coster-Mullen have to say about the flight of Bockscar? “That mission was a sorry mess from the get-go,” he said recently. “And ramifications have carried on through many decades.”

Ashworth was in charge of the nuclear part of the mission, where, in his words, “We had tons of stuff out there to assemble into bombs … 24 hours per day, 7 days a week.” Even though Fat Man had been pre-assembled by the experts at Los Alamos in peace and quiet, a few key components of the bomb then had to be taken apart in order to safely ship Fat Man halfway around the globe. “This saved the people on Tinian of a lot of heavy handling work, and their job was only to remove the two explosive blocks, insert the pit and close it up,” Ashworth said.

Still, this approach meant that the atomic bomb needed to be reassembled, in a remote part of the Pacific, during war-time, thousands of miles away from where it had first been conceived. (The active materials, such as each bomb’s all-important plutonium “pit”—the critical core component—were shipped separately and hand-carried.) Because it was all so complex and intricate, Ashworth flew on board the plane with the finished product. To my mind, he had no reason to alter the facts. This is his account of those final hours on the plane with Fat Man, as Ashworth told them to me over 15 hours of face-to-face interviews.

Prologue to the flight. The heart of Fat Man was a grapefruit-sized core of plutonium—a newly manufactured, radioactive element that is more stable than most isotopes of uranium and more powerful. It was shiny, slightly warm, and weighed about 14.1 pounds. And someone had to carry it to the tiny Pacific Island of Tinian, where the bomb would be assembled and loaded on to a B-29 bomber.

The task fell to a young scientist—he drew the short straw—named Raemer Schreiber, whose story is recounted here for the first time. His unpublished diary (shared with me by his daughter, Paula) recounts how on July 26, at Los Alamos, colleagues handed him the plutonium core, nicknamed “Rufus,” which he placed in a little, open-wire carrying case that resembled a milk crate. They also asked him to transport a huge wheel of cheese, presumably for the nuclear scientists waiting on Tinian. With the core in his lap, Schreiber bounced over dirt roads on the way to Albuquerque where he boarded an empty C-54 aircraft. He knew the core could not explode without a detonator.

As described in his diary, Schreiber sat on a hard wooden chair strapped inside the big plane all the way to Tinian. Like everyone working on the Bomb, he was exhausted. So he slept sitting up, sometimes holding the bomb case in his lap. At one point, over the Pacific, he went up to the cockpit to get a better view of what was causing turbulence. One of the crew came up behind and tapped him on the shoulder: “Whatever that thing is you got, it’s rolling around the back of the plane. Maybe you want to corral it.”

The wire container had tipped over, the first in a series of mishaps. Schreiber quickly fetched the nation’s most technologically advanced wartime treasure, tied it to the leg of his chair, and went back to sleep.

Schreiber landed on Tinian on July 28, local time. Located in the Marianas archipelago, on the other side of the International Date Line, the island was hot and muggy; it rained almost constantly. No one had thought about where to put the plutonium carrier, so the Los Alamos scientists already on Tinian stuck it in the back of the Quonset hut where they slept. Then they took snapshots of themselves holding all the plutonium there was in the world.

In February, Ashworth selected Tinian because it was one of the first liberated islands that had a runway long enough for a heavily loaded B-29 to take off and was close enough to the Japanese mainland for the planes to make round trips. But B-29s were notoriously unreliable flying machines, especially in the early days, when they had been rushed into service without complete testing. Until the designs improved, many engines overheated, caught on fire, and caused the planes—full of bombs and fuel—to crash on takeoff. The end of Tinian’s runway was littered with a pile of wrecked B-29s. (The planes used for the atomic bomb runs had been modified and upgraded, which was reflected in the planes’ official designation: “Silverplate.”)

The men waited. The weather remained dreadful. The crew talked about the possibility of the Japanese surrendering but the Hiroshima bomb did not make that happen. The scientists wanted the enemy to think they had an endless supply of atomic bombs but there was only one more immediately available: Fat Man, whose core lay in the back of the hut. (There were other cores in various stages of completion.)

Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, who had piloted the plane carrying Little Boy to Hiroshima, was one of the people involved with deciding when to drop the second bomb, scheduled for August 11. The primary target was Kokura, site of one of Japan’s largest munitions plants. Nagasaki was the backup target. When five days of bad weather was forecast (including a typhoon), the mission was moved up to August 9. The change meant that corners inevitably had to be cut to get the bomb airborne in time.

These shortcuts imperiled the mission several times. For example, late in the evening of August 8, a young nuclear engineer, Bernard O’Keefe, and an assistant worked to fit a casing over the core, setting fuses and turning screws. They crouched in the only air-conditioned room on Tinian with a bare electric light bulb. Sometime before midnight, O’Keefe stepped back to make a last check.

As elaborated in my conversations with Ashworth, O’Keefe tried to plug a cable into the firing unit. It didn’t fit. He told himself he must have been doing something wrong. He was too tired, not thinking straight. O’Keefe realized he was trying to fit a female plug to another female plug on the end of the cable. He walked around the weapon and on the other side saw two male plugs in the same position. That wasn’t right. But they were soldered on that way.

He called his assistant and asked him to look at the plugs. He confirmed that they were put together wrong.

O’Keefe fumed. He couldn’t call the whole show off because of some stupid mistake. He’d just have to fix it, unsolder and re-solder the damn thing. He asked where there was an electrical outlet.

They finally located one two rooms away, so O’Keefe had to find extension cords. Then he strung two cords together and heated up his soldering iron. He recalled that sweat was pouring off his body and the assistant was terrified.

“Sir, that is dangerous.”

“Right,” said O’Keefe. “Then go hide somewhere, although if this blows up it won’t make much difference where you hide.”

O’Keefe carefully unsoldered two connectors, switched them, re-soldered them, and stood up. Then he sank down to the floor. It was midnight. Fat Man was now ready to be fully armed, but with green safety plugs engaged. Soldiers came to roll the bomb out and hoist it into the belly of a B-29 named Bockscar(sometimes spelled as Bock’s Car).

Army Major Charles W. Sweeney piloted Bockscar. Major James I. Hopkins piloted a second plane, Big Stink, there to observe the strike and take photos. Captain Frederick C. Bock—who was normally in command of the Bockscarnamed after him—piloted a third plane, The Great Artiste, which carried blast measurement instruments and observers. Two weather reconnaissance planes had taken off an hour earlier.

To accommodate the 10,800-pound Fat Man, Bockscar was stripped of all its guns. It had to carry enough fuel for the long trip to the Japanese mainland. On takeoff, it was seriously over its designated weight for safety.

Before the crew boarded the plane, Tibbets held a briefing where he announced last-minute changes. According to Ashworth, Tibbets announced that his good buddy Sweeney would pilot Bockscar instead of Bock. There would be glory in it for his friend. Second, due to bad monsoon weather, the rendezvous point for the three planes was changed from Iwo Jima to Yakushima, an island off the southern tip of Japan. Third, Bockscar was to fly at altitudes higher than its normal 9,000 feet if it encountered foul weather over the Pacific. This meant greater fuel consumption.

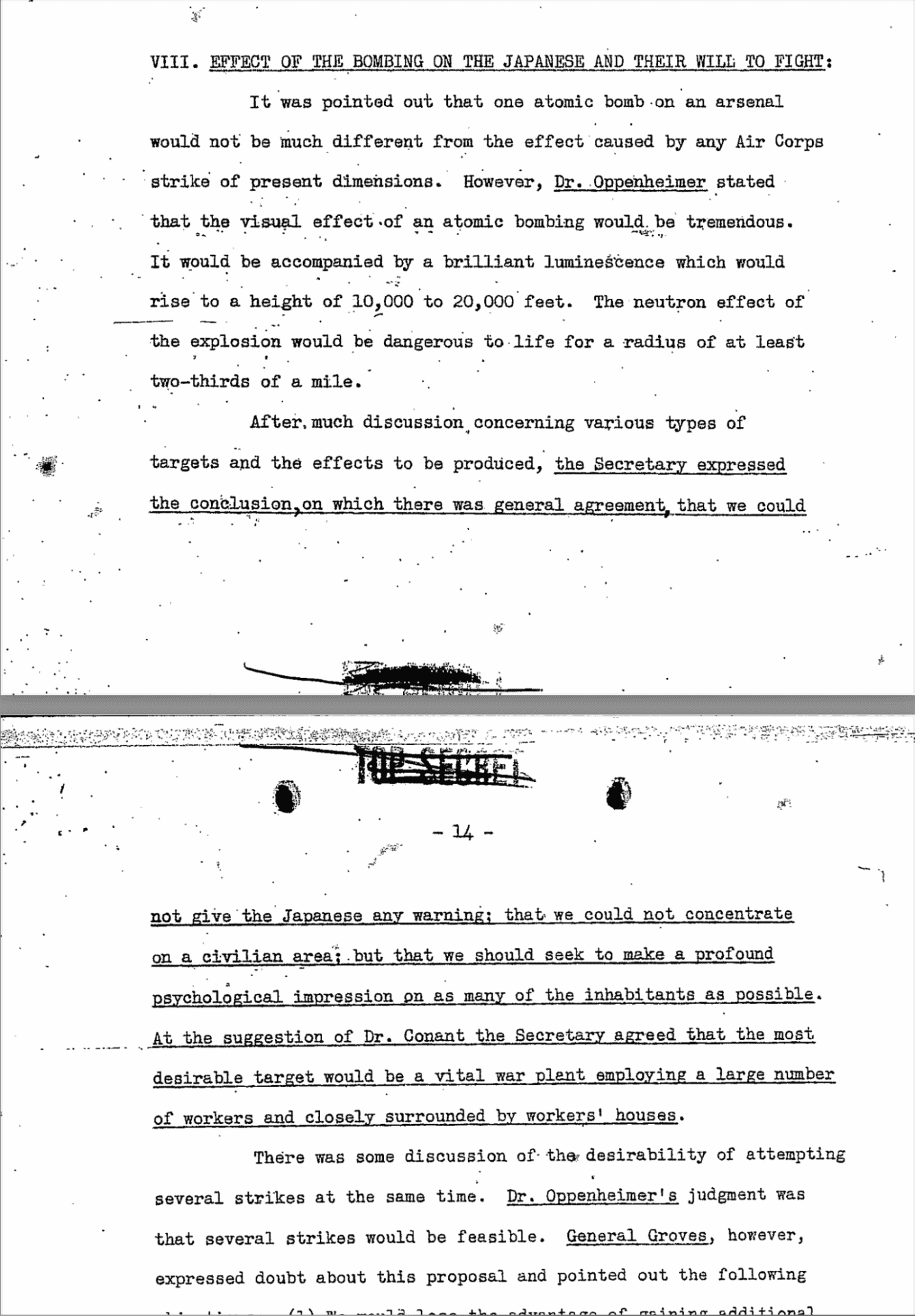

Finally, Tibbets gave two clear instructions. Wait no more than 15 minutes at the rendezvous point before proceeding to the Japanese mainland. And drop Fat Man visually instead of using radar. The target must be photographed. The head of the scientific project that developed the atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer, wanted a clear demonstration of the power of the new weapon. He had told the US Secretary of War, Harry Stimson, that “the visual effect of an atomic bombing would be tremendous” and “we should seek to make a profound psychological impression on as many of the inhabitants as possible,” as was duly noted on pages 13 and 14 of the minutes of their July 31, 1945 meeting and then stamped “Top Secret” (and now declassified).

As the men prepared to board the plane, Raymond Gallagher, the assistant flight engineer, said: “The feeling in our hearts, when we heard about the briefing, was very, very low.” Following standard procedures, the men all dropped their wallets into a barracks bag near the door. “Truthfully, I think I will never pick it up,” he said.

On the plane. Once onboard,at 2:15 a.m., the crew went through a final pre-flight check. It went well until Sweeney’s flight engineer, Master Sergeant John D. Kuharek, tried to access 640 gallons of fuel in Bockscar’s reserve tank in the tail of the aircraft. It provided ballast as well as a margin of safety for getting back to Tinian. Kuharek flipped a switch. The fuel did not move. He tried again and again. No dice. There was no time to replace the fuel pump. Another mishap.

Regulations required that the flight be cancelled. Sweeney ordered everyone off the plane. The men got off, stood around nervously and looked to Tibbets and base commander Brigadier General Thomas F. Farrell for a decision.

According to Ashworth, Tibbets said that they were fast losing the weather. And the Hiroshima flight had been a milk run, with no problems—they’d got back to Tinian and never touched that fuel in the reserve tank.

“I say, ‘Go.’ ”

Farrell, somewhat more reluctantly, agreed. It was a go.

The men on the runway looked at each other, then climbed back into the plane.

Like all B-29s, Bockscar was temperamental. According to Ashworth, Fred Bock probably could have twiddled and fiddled the controls to make the pump work. But Charles Sweeney was in charge. Although a good pilot, he was not as familiar with the plane’s quirks.

Here is where Dick Ashworth’s story begins to get personal and diverge from conventional accounts. He told me that Sweeney was an Army man, accustomed to following orders. Ashworth, on the other hand, was a Navy man, accustomed to getting a mission accomplished no matter what came his way. In other words, the Navy gets things done. The Army follows orders. And that is where the conflict, which nearly caused the mission to fail, began.

Such conflict between operating systems is a military classic—called a “purple operation,” from the mixture of Army red and Navy blue. It even had a code: JANCFU for “joint army navy combined foul up” which was a cousin of “SNAFU,” military vernacular for “situation normal, all f***ed up.”

Bockscar lifted off at 3:47 a.m., using the whole length of an 8,500-foot runway. Palm trees below bent down as the plane pulled up, as if the Earth were reluctant to let it go.

Two minutes later Sweeney turned the controls over to his co-pilot, 1st Lt. Charles Donald Albury, and took a nap. Back in the belly of the plane, Ashworth removed the green safety plugs and replaced them with red arming plugs. Then Ashworth told me that he dozed for a few minutes with his head resting on the Bomb, which hung from a grappling hook, swaying slightly. It was several hours to the rendezvous point.

At 7:00 a.m., after about three hours in the air, Ashworth told me that his assistant weaponeer, Lt. Philip M. Barnes, awakened him.

We don’t know to a 100 percent certainty what was said next, but Ashworth recalls the following exchange. What happened does not seem to have appeared in any official histories, but Ashworth swore to me it was true.

“Hey, Commander, Ashworth, Dick.” Barnes called him first by rank, then last name, then first name, with increasing terror. “Hey, we got something wrong here. We got a red light going off like the bomb is going to explode right now. Armed, it’s armed. Fully armed, look at this. Can you take a look, what is going on with this?”

A red light that had been blinking steadily suddenly sped up, flashing a dire warming.

Ashworth said he shook himself awake. “Are you sure? Oh my God.” He saw the red light. “There is something … do you have the blueprints? This bomb can pre-detonate if we drop below a predetermined level. What’s our altitude? Where are the blueprints?”

Barnes and Ashworth unrolled the blueprints and started checking. They took the casing off the bomb, and scrutinized the switches. After 10 tense minutes, they saw the problem. Two switches had been reversed, a mistake in the arming process. Barnes flipped the two tiny switches into their proper positions and the red light stopped blinking.

Ashworth went back to sleep.

Barnes sat on a small stool in front of the bomb and never took his eyes off the light.

The bad weather continued. Their wings were occasionally bathed in St. Elmo’s fire—a non-threatening electrical phenomenon that was nevertheless scary under the circumstances. Shortly after the incident with the red light—which no one on the plane other than Barnes and Ashworth knew about—they slowly climbed to 30,000 feet to arrive at the rendezvous point at roughly 9 a.m. Ten minutes later, they spotted the instrument plane. But the third, with the photographic equipment, did not appear.

Sweeney began to circle the island, waiting for the third plane. He circled for 15 minutes, then 30 minutes, then for 45 fuel-guzzling minutes.

Sweeney turned to his co-pilot. “Where the hell is Hoppy?”

James “Hoppy” Hopkins, piloting The Big Stink—another modified Silverplate B-29, able to fly at higher altitudes than earlier models—was circling above them at 39,000 feet, looking anxiously for the other two planes.

Sweeney later told his superiors that Ashworth commanded him to keep circling. But Ashworth told me a very different story. He said that if he had been able to see which plane was with them (it was The Great Artiste with the instruments), he would have argued to immediately proceed onward. But from his small window, Ashworth could not readily see all that was going on. He wanted that instrument plane, but the photo plane was not much of a priority to him—especially if waiting for it meant endangering the entire mission. But Ashworth could not make his concerns known, even though he was not far from the pilots’ seats. Although the crew all had headsets, Ashworth did not, so they and he had to make themselves heard over the engine noise to communicate. This was normally OK, but this was not a normal situation. Adding to the tension, Kuharek made it clear they were beginning to be critically short of fuel.

“We waited and waited for the last plane,” Ashworth told me. “Sweeney had in mind that we were supposed to have three airplanes going to target. I think he wanted a perfect operation. The net result was we wasted 45 minutes of precious gasoline. Finally I said to Sweeney, proceed to first target.” Once again, the mission was imperiled by multiple mishaps.

Above them, at 39,000 feet, Hopkins hovered, desperately looking for the other planes, at the wrong altitude. At last, frantic, he broke radio silence and radioed back to Tinian.

He said, in code, “Is Bockscar down?”

But on Tinian the first word of the transmission was dropped. They heard: “Bockscar down.”

Commander Ferrell was having breakfast. When he heard the news, he ran outside his tent and threw up. He then cancelled a contingent air-to-sea rescue operation. Despair settled on the island. They believed that they had lost one of the weapons that was to finally end the war.

Kokura’s lucky escape. But Bockscar was not down. It flew on toward Kokura, followed by The Great Artiste, as The Big Stink continued searching for it at the wrong altitude.

They arrived at 10:44 a.m. to find Kokura blanketed in thick smoke. On the ground, three employees of the Yawata Steel Works had been burning drums of coal tar to lay down a smoke screen, on the orders of their supervisor. And steelworker Satoru Miyashiro and his co-workers had heard about Hiroshima.

Bockscar began a bombing run but the bombardier, Kermit Beahan, could not see enough to do a visual drop. As the B-29 pulled away in futility, flak began bursting all around them. Kokura was one of the most heavily armed cities in Japan because of its munitions factories and steelworks. Bockscar had no guns to defend itself, and in any case, guns would have been no protection against flak.

Sweeney announced he would do a second run over Kokura. Ashworth told me he was steaming. Tension in the plane mounted. Meanwhile, the men were calculating the amount of remaining fuel. Second Lieutenant Fred Olivi, wrote in his diary, “Our gas is going fast at this altitude, and we can’t wait any longer.”

Again Sweeney began to circle for another run. At this point Ashworth went to talk with Sweeney.

They heard a worried voice from the tail gunner, Sergeant Albert T. ‘Pappy’ Dehart. “Major, flak is closer.”

“Roger,” said Sweeney.

Pappy’s voice was a squeak: “Major, flak right on our tail and coming closer.”

Then Second Lieutenant Jacob Beser, who was in charge of radar counter-measures, began to pick up signals near Japanese control frequencies. Japanese fighters were darting up fast.

Then Staff Sgt. Edward K. Buckly, the radar operator, broke in: “Skipper, Jap Zeros coming up at us. Looks like about 10.”

“Let’s try from another angle,” Sweeney said.

Telling the tale all these years later, Ashworth says that he was effectively stuck, administratively, in what he called “the bilge” (a Navy reference to the bowels of the craft)—unable to see or hear all that was going on, with his fate in the hands of someone else, and more than dubious about the choices the skipper was making. He knew that Sweeney had never flown in combat, and that changes decision-making, whatever the orders are. At this point they were on their own, alone, in the air, and carrying an atomic bomb. Ashworth had been in combat, and knew that at some point you scrap orders and do the best and only thing you can. You complete your mission. You save your men if you can.

It was not clear who was in charge. Sweeney, the Army guy, piloted the plane. Ashworth, the Navy guy, was in charge of the bomb. As the weaponeer, Ashworth wanted to get to the target and make the visual drop as specified. In retrospect, he was in charge but the mishandling of their orders led to the plane nearly falling out of the sky.

They didn’t have enough fuel to make any more runs.

Sergeant Abraham Spitzer, the radio operator, later said: “I could see Commander (Ashworth) was struggling within. He seemed perplexed. What to do? Disregard orders, risk a return to Okinawa and the lives of the men aboard, perhaps the loss of the bomb in the ocean to save our own necks? All that weighed heavily on his mind. Desperately, he made up his mind. Casting aside all consideration he told the major it was Nagasaki—radar or visually, but drop we will. We cheered. Nagasaki, here we come.”

Nagasaki. At 11:32, Bockscar banked and turned south. Sweeney tipped the aircraft wings to indicate that The Great Artiste should follow. Ashworth told me that the two B-29s nearly collided midair—a detail often overlooked in subsequent accounts.

They flew the shortest route overland to reach Nagasaki, 95 miles away. They did not have enough fuel to make it back to any US base. Ashworth told me that, at this point in the mission, he was prepared to take all responsibility, even if it meant a court martial. If the target could not be seen visually, he would use radar. It wouldn’t be what the brass wanted but would get the job done.

He also told me that he did not think any of them would survive the mission. There was a very slim chance they might make it to the recently liberated island of Okinawa. But he did not count on it.

The navigator, Fred Olivi, recounted how he wondered if the Pacific Ocean would be cold when they ditched.

At 11:50 a.m., Bockscar arrived over Nagasaki.

Big fluffy clouds drifted over the city. Ashworth said that, given the fuel situation, he had only had one chance to drop the bomb. “I felt it was my responsibility to try a radar approach. The only alternative was to ditch the plane with the bomb.”

Bockscar began a five-minute bombing run. When the bomb-bay doors opened, Ashworth spoke to Beahan, the bombardier. “Use the radar.”

As large holes pooled through the puffy clouds, Beahan shouted: “I see it! I see it! I got it!”

Sweeney said, “Okay, you own the plane.”

Beahan had about 45 seconds to set up the bombsight, to kill the drift, and to kill the rate of closure on the target. Then: “Bombs away!”

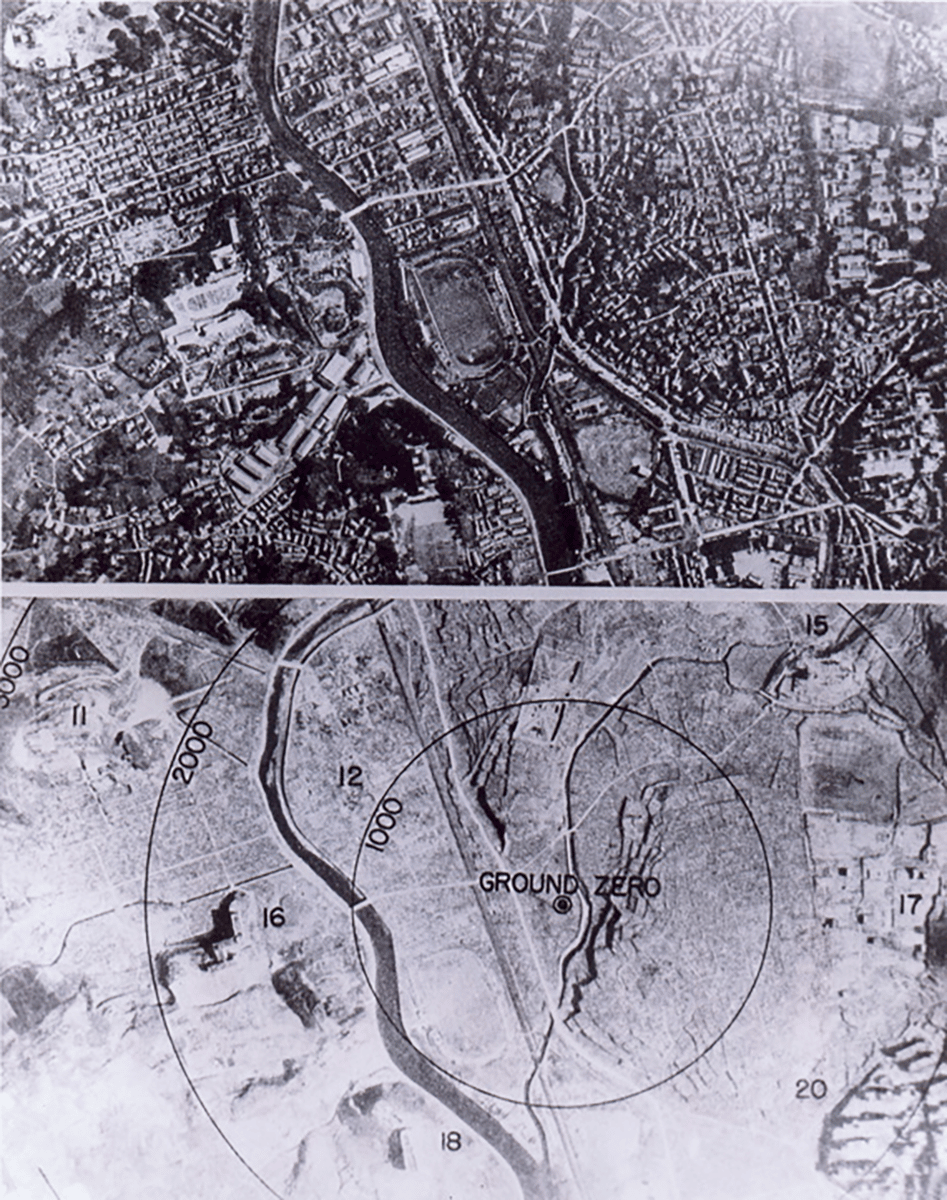

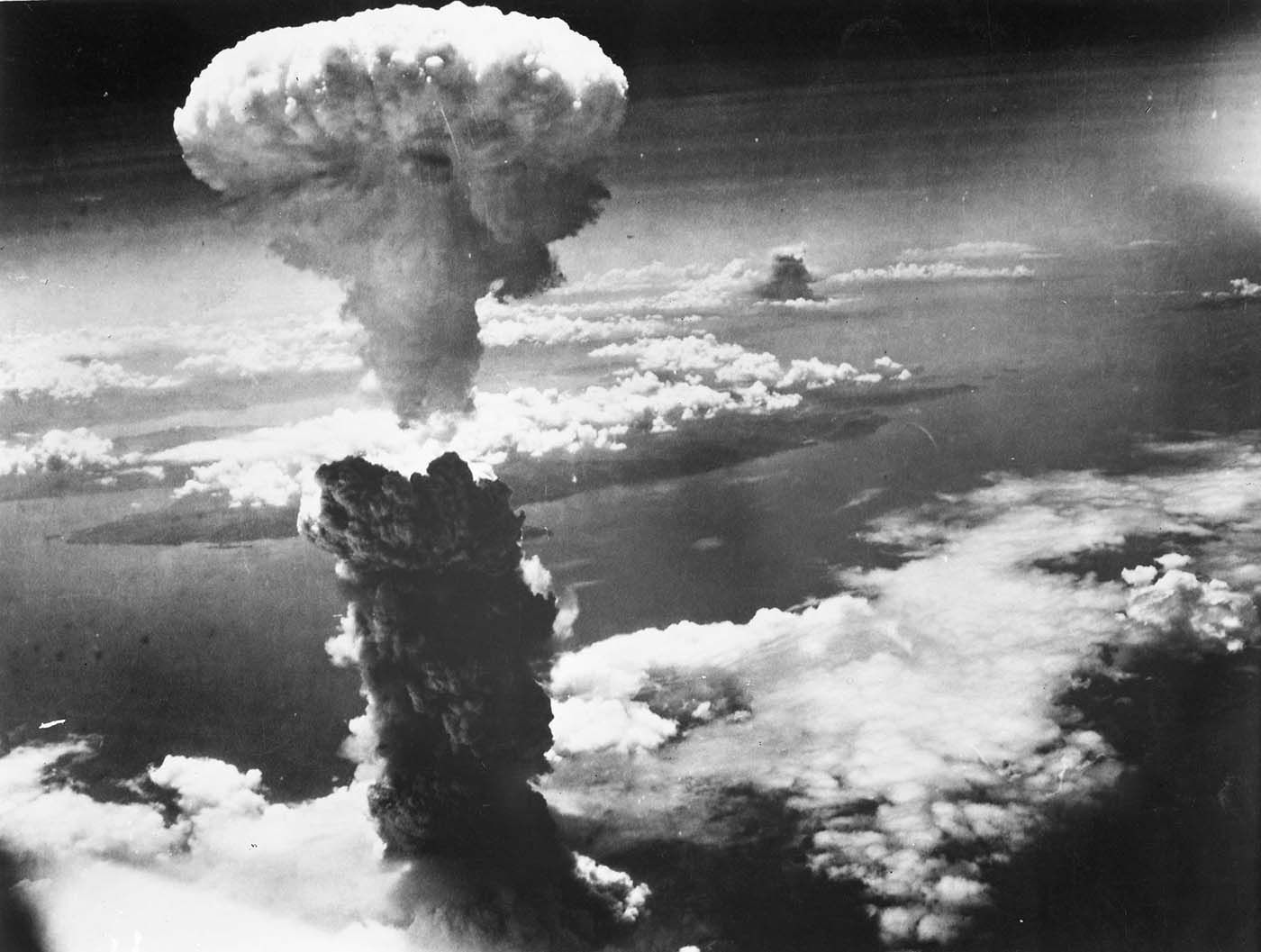

Fat Man fell from the plane for 20 seconds and, at 12:02 p.m., exploded at an altitude of 1,840 feet with a force of 22,000 tons of TNT.

The bomb-bay doors snapped shut. Inside the plane, men were thrown down by several shock waves. Beser was pinned to the floor and thought the plane was going to be torn apart.

Olivi described the mushroom cloud: “It was bright bluish color. It took about 45 or 50 seconds to get up to our altitude and then continued on up. We could see the bottom of the mushroom stem. It was a boiling cauldron. Salmon pink was the predominant color. We couldn’t see anything down there because it was smoke and fire all over the area where the city was. Everybody was concentrating down there and I remember the mushroom cloud was on our left. Somebody hollered in the back: ‘The mushroom cloud is coming toward us.’ This is where Sweeney took the aircraft and dove it down to the right, full throttle, and I remember looking at the damn thing on our left, and I couldn’t tell for a while whether it was gaining on us or we were gaining on it.”

At 12:05 p.m., Sweeney kicked the plane over into another dive just in time to avoid running into a cloud of atomic ash and smoke, which was still climbing up.

They were 457 miles from Okinawa. The Great Artiste, which had dropped a suite of instruments right after the bomb exploded, was on their tail. Both planes were low on fuel but Bockscar was running on hope. Because of radio silence, they could not talk to each other.

Ashworth said he told the crew to say goodbye to one other and put on their Mae West life jackets. They would probably have to crash-land in the ocean. There was a very small chance of a rescue. Except for The Great Artiste, no one else knew they were in the air. And although they didn’t know it, as far as the military was concerned, their plane had been lost many hours earlier.

As they left the Japanese shore, Sweeney sent an international distress signal. “May Day. May Day. May Day.” There was no response.

They were at 30,000 feet and could descend, almost in a glide, with minimum fuel consumption. About five minutes out of Okinawa, with heavy air traffic moving to and from the runways, all fuel tanks read empty. Sweeney frantically tried to call the busy control tower on Okinawa but got no response. They had only once chance at landing. He yelled, “Fire every goddamn flare in the airplane.”

Olivi later wrote: “I took out the flare gun, stuck it out of the porthole at the top of the fuselage and fired all the flares we had, one after another. There were about eight or ten of them. Each color indicated a specific condition onboard the aircraft.”

As far as the tower was concerned, Bockscar was out of fuel, on fire, had wounded men, and every other crisis a plane could have.

Still firing flares, Bockscar touched down at 1:51 p.m. going 140 miles per hour—about 30 mph too fast. It bounced 25 feet in the air before settling down. At touchdown, the number two inboard engine died. This actually made the plane easier to handle. Sweeney and Albury both stood hard on the brakes and reversed the propellers to slow down the plane. They passed rows of parked B-24 Liberator heavy bombers that were fueled up and loaded with incendiary bombs, but didn’t smack into any. At the end of the runway, they made a full 180-degree turn and headed to a paved area for parking heavy vehicles, rolling on fumes.

Then stopped.

Ambulances, fire trucks, and jeeps pulled up. Sweeney told the men not to tell anyone about the mission. Ashworth and Sweeney jumped into a jeep that took them to headquarters.

Okinawa base commander and aviation pioneer James Harold “Jimmy” Doolittle had been there two weeks. He looked at Ashworth and said, “Who the hell are you?” Ashworth bristled and said, “What the hell is wrong with your control tower? We are the 509, Bockscar. We dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki. Sir, I think we were a little off target.” He stopped.

“Bockscar?” said Doolittle. “You, you’re not lost? Thank God you didn’t hit those B-24s. Just missed one hell of an explosion. Guess you already had one hell of an explosion.”

He looked hard at Ashworth. “We heard you were down.”

Later, Doolittle remarked to a friend of mine in New Mexico, Linda Davis, that the landing was “the scariest thing I ever saw.”

A little later, the crew sat in the mess hall eating Spam. The third plane, piloted by Hopkins, arrived three hours later after circling Nagasaki and photographing the damage with an unofficial camera that a young physicist, Harold Agnew, had snuck on board. This was fortuitous. No one on the plane knew how to operate the official camera because the man assigned the task was kicked off before takeoff because he had hastily grabbed a raft instead of a parachute.

At about 5:00 or 5:30 p.m., all three B-29s left Okinawa for Tinian Island, arriving at 10:45 p.m.

Unlike the Enola Gay that had bombed Hiroshima, Bockscar was not greeted on its return with fanfare and praise. The military did not push the Bockscar story or decorate the men who flew the mission—unlike what happened with the Enola Gay’s crew. There was talk that Sweeney should be court-martialed for disobeying orders, but nothing came of it. We had won the war. There was no point in making the military look bad. There was no need to do a formal review, which could reveal the embarrassing mishaps, just as there was no need to assemble the other cores or fly more missions. (An August 16 teletype to Washington said, “Although they are completely ready, F-101, 103 and 102 will not be dropped due to surrender agreement. An active sphere for F-32, it is also assumed, will not be sent.”) A full-scale land invasion of Japan was averted, saving what the Joint Chiefs of Staff estimated would be tens or even hundreds of thousands of lives—although the exact figures are one of history’s great “what if” questions.

The future was all that mattered.

Postscript. Near the end of his life, Sweeney wrote a highly controversial and factually disputed memoir called “War’s End: An Eyewitness Account of America’s Last Atomic Mission.” For example, he asserted that Ashworth ordered him to circle the rendezvous point for 45 minutes. He also wrote that Bockscar circled Okinawa before landing and that the plane had enough fuel in its tanks. Many surviving members of the mission were reportedly outraged. In response to the book, Tibbets revised his own autobiography to set the facts straight.

Ashworth told me that he never wanted to get drawn into these disputes. He felt they tarnished the image of the military he loved. He did write an autobiography but thus far it has been lost to historians. We do have several interviews (including the ones with me), speeches to the Los Alamos Historical Society, and recollections of others who flew with Ashworth—and who admired him greatly.

I’ve been telling Ashworth’s story for the past 10 years to select, interested audiences around the country. As a child, I was always interested in the bomb and talked to many scientists about what they thought; by accident, I watched some of the first films of Hiroshima and Nagasaki when they were shown to a conference of scientists at Los Alamos. The extraordinary nature of the bomb was clear to me, and I have interviewed many people associated with it, but out of a personal, not professional, interest. With the 70th anniversary of the bombing, I felt it was time to see Ashworth’s account in print.

As the coronavirus crisis shows, we need science now more than ever.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent, nonprofit media organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

My Dad was the bombardier-navigator on a B-25 mission which was in the area of Nagasaki when the bomb was dropped so saw the explosion from the air. He never told me that, but my brother let it be known at his funeral. I’m still amazed that he never told me, although one of my nephews said “He told me”.

My father was on a ship in the Pacific when the bomb was dropped. He would have been part of the deadly invasion. I was born in 1947.