AI isn’t choosing our artistic future, we are

By Katie Peyton Hofstadter | October 27, 2022

Illustration generated by OpenAI’s DALL-E 2.

Illustration generated by OpenAI’s DALL-E 2.

Like other technologies that have come before it, artificial intelligence, commonly known as AI, is changing art forms that have existed for millennia. It will also be instrumental in the creation of art forms not yet imagined. In the future, there will be three or four types of intelligences creating art: human artists, humans and AI working collaboratively, machine learning models that don’t require human initiation but still lack sentience, and finally, in the event technologists create truly sentient artificial intelligence, artificial general intelligence or AGI capable of self-creating art. In all cases, it’s unlikely that AI will destroy art, but it will certainly transform it—a process that has already begun. Humans are making choices about how that will happen, and they are making those choices right now.

In the late 19th century, the camera didn’t destroy painting, but it did change the world of visual art. Freed from the pressure to convincingly depict reality, artists embarked on experiments with aesthetics and meaning. In the early 20th century, the readymade (the use of found and manufactured objects as art) didn’t destroy sculpture but released some artists from narrow notions of authorship and craftsmanship. This liberated sculptors to focus on theory and concept.

So, one might say the world has always asked existential questions about new technologies. Of course, it’s not entirely accurate to compare machine learning to a 19th-century camera that does not make decisions and cannot learn—or learn to operate itself. Merging human practices with machine learning, as we move towards a future of AGI, edges humanity towards a visible horizon where human and machine intelligences intersect and interact. Or is it a precipice?

For her project, “ماه طلعت، Moon-faced,” Allahyari uses a carefully researched and chosen series of keywords with a multimodal AI model to generate a series of videos from the Qajar Dynasty painting archive (1786-1925). Through this collaboration, the machine program learns to paint new, genderless portraits, in an effort to undo and repair a history of Westernization that ended the course of nonbinary gender representation in the Persian visual culture. (Morehshin Allahyari, ماه طلعت، MOON-FACED, 2022. Video and text courtesy of the artist.)

Today, the labor of visualization can be quickly accomplished by AI, raising questions like which new forms of creativity this might free some artists to pursue, and what their next experiments could reveal. Already, contemporary artists like Mario Klingeman, Sasha Stiles, Lauren Lee McCarthy, Morehshin Allahyari, Carla Gannis, and Connie Bakshi are examining this new potential by collaborating with machines; building their own training sets to demonstrate bias; and generally helping the world talk about how deep learning and neural networks are affecting humans, both today and in a variety of speculative futures. Far from working towards the destruction of art, these artists are using AI to expand the field of creativity.

But it’s also worth a critical examination of how humans will be used in return. Humans design the models and generally provide the training sets. It’s already easy to see that just scraping the internet for training data encodes explicit bias that endangers marginalized communities. It is imperative today to design the training process for Ais with intention, rather than turning a blind eye and hoping for the best.

In addition, the inputs for current machine learning regimes come from the same artists whose paid work the models may replace: illustrators, designers, writers, composers, translators.

That said, if artists and their supporters are dedicated to systems that advance culture rather than cannibalize it, AI can be an incredible opportunity for learning and collaboration. That’s a big if. The systems for training AIs are far from set, and those who create artificial intelligence programs are making critical decisions right now.

Today, AI-generated images are created by models that scrape existing images produced through creative labor (with their viewpoints and biases), along with responses to those images, essentially creating variations on pre-existing images and stylistic choices. While this process offers the opportunity for collaboration and learning, it also has drawn reasonablepushback from artists whose work has been used as training data without permission or compensation. Often, artists’ names—or the styles they helped create—are even used as prompts. And while AI is routinely credited as a co-creator, the human creators whose work fed the machine often are not mentioned or paid.

Fundamentally, it’s problematic to create a system that scrapes creative labor, then expect that material to keep producing to feed the next generation of algorithms. In other words, if the AI-powered creators are starved of inputs, there’s no reason to believe those outputs will continue to evolve. If companies are using human labor to feed machines, who is designing the ethical framework, who is enforcing it, and who is studying the impact? If the answer to any of these questions is whoever can make the most money in the shortest time, by paying the least for creative labor, then yes: The arts sector will suffer, both human and machine. As Jeanette Winterson points out in “Love(Lace) Actually,” from her 2021 collection, 12 Bytes: How We Got Here. Where We Might Go Next, there is great potential for human-AI collaborations in novel-writing software. But without Virginia Woolf, GPT-3 will not produce her.

“… if I type in: Cat falls down mineshaft and discovers a secret world of giant mice with computing skills, novel-Writer will help with all the components of character (probably a lot of characters if they are mice), and plot twists – and yippee, I have written a novel (about mice). On the other hand, if I put in: Young man in the reign of Elizabeth the First wakes up one morning in Turkey as a woman, I probably won’t write Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. Anyway, it’s been done.”

If creative growth is to continue, now is the time to invest resources to support and equitably grow the arts, education, libraries, and culture—rather than taking the easy bait and allowing a few corporations to scrape existing artistic troves now for all they’re worth, and perhaps one day sell them back to advertisers. Humankind has built a civilization of enormous wealth and capabilities, though it is not equally distributed. Innovators and visionaries in the tech and art world have the ability to choose the world they want. AI isn’t making that choice—people are.

“As an artist that works with code,” writes Lauren Lee McCarthy, “I think in terms of scripts, both the social and technical ones.” In LAUREN, McCarthy performs the role of a personal assistant without volition, imitating the role of (usually female-voiced) programs like Alexa or Siri. Instead of shouting at an AI, participants shout (and sometimes, softly speak) for Lauren, who answers the requests without judgment. “I attempt to be better than an AI, understanding them as a person and taking action in anticipation of their needs and desires.” Lauren Lee McCarthy, LAUREN, 2017. (Video: LAUREN Testimonials, 2017, directed by David Leonard.)

I don’t wring my hands over the idea of transformational change in art. In 50 years, art may be as unrecognizable to me, today, as Christo and Jean-Claude’s wrapped Reichstag would be to a European court painter. Yet, that court painter would find much to recognize in Amy Sheridan’s painting of Michelle Obama. Today, society recognizes the merits of both artworks. One doesn’t negate the other.

So those who make and support art should embrace this technology, yes, and learn from it, collaborate with it—and also make conscious decisions about the future. If the wealth generated by an AI workforce is used to create income security for those who need it, for example, the world might see an AI-enhanced explosion of creativity and diversity in art. This type of explosion would see exciting and enriching new forms of storytelling, community, and criticism.

Now, as in the past, art is made for humans. People love it for its beauty, for asking questions and subverting answers, for challenging society, for sounding alarms and sometimes, for simply making individual human beings feel seen. Even as humans merge with machines, it’s hard to see why they would stop creating or loving art.

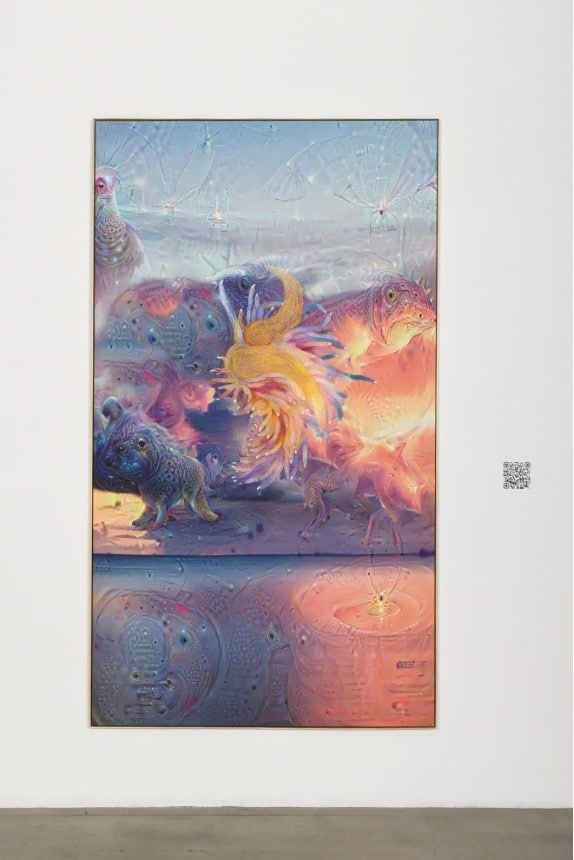

In 2015, the internet was flooded with images created with Deep Dream, a program that used a neural network to find and enhance patterns in input images. Today, artists like Gretta Louw use the technology with a heavy dose of metacommentary. (Installation view of Gretta Louw’s During Dark Days We Must Dream in Double Time, 2021 Digital embroidery and digital print on linen, and NFT .mp3 file via QR-Code. Courtesy of Honor Fraser Gallery, Los Angeles; photo by Jeff Mclane. )

Special: Will AI destroy art? Or just change it?

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: AI, art, artificial intelligence, images

Topics: Artificial Intelligence, Disruptive Technologies