Is AI art’s true foe?

By Martin O’Leary | October 27, 2022

Illustration generated by OpenAI’s DALL-E 2.

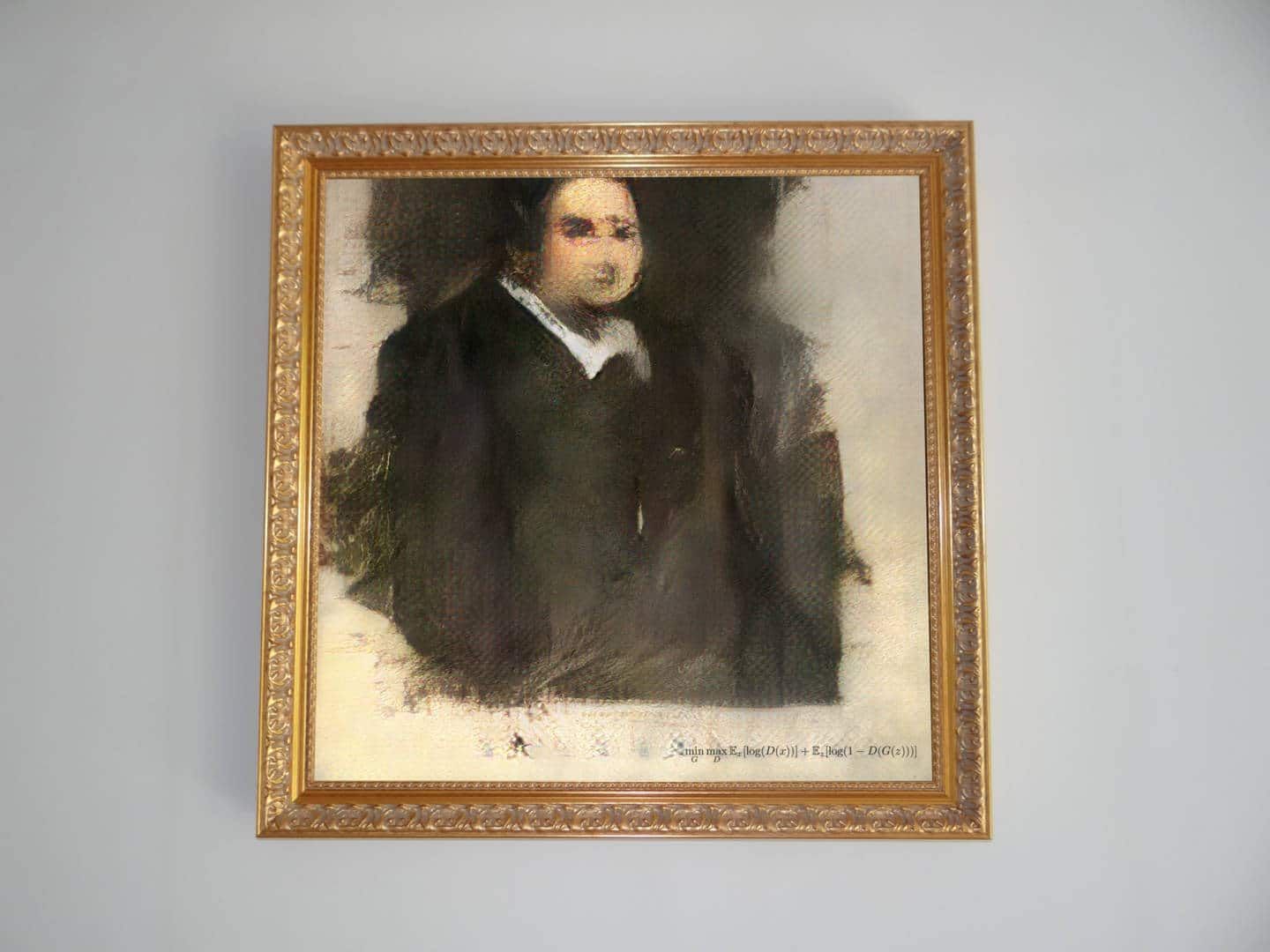

Illustration generated by OpenAI’s DALL-E 2.

The automation of art evokes strong emotions, in part because art is an aspirational profession, set apart from common work. Millions dream of quitting their jobs to become artists, even if on some level they understand the economic realities of such a precarious job. The mystique of high art leads us to imagine artists as a special class of blessed individuals, rather than workers selling the products of their labor.

In 2018, Edmond de Belamy, a mediocre AI-generated portrait of a man dressed in a dark suit by the Paris-based art collective Obvious, sold at Christie’s Auction House for $432,500 in a seeming vindication of AI’s potential. AI-assisted or not, most artists do not get to sell their work at Christie’s. Instead, the careers of many in art comprise of a succession of unstable and often deeply unglamorous freelance gigs. These can include illustrations for corporate brochures, décor for hotel rooms, advertising material and product catalogues. This is image-making, not as high art, but as an industry driven by commercial needs and cost-benefit analyses. It is in this setting that we can expect AI to outcompete traditional artists.

If AI kills art, it will join an illustrious club that includes movements like realism, impressionism, and abstraction, and other media such as film and photography. In truth, the art world thrives on supposed art killers. Gallerists and auctioneers salivate at the idea of showing (and selling) the first work employing some new gimmick that purports to upend the art world. AI-produced art has already been deployed repeatedly to drum up interest from the novelty-obsessed art market. The sale of Edmond de Belamy will not be the last time some technological spice is used to pump the price of an unimpressive image, but the availability of cheap AI-generated images, which are good enough for commercial purposes, is likely to have a much larger impact on most artists’ lives.

In similar ways, AI has already transformed the translation industry, where machine translation is now the norm. Professional translators are still needed for higher calibre work like important legal or technical documents, or for nuanced creative texts such as fiction and poetry. But the bread and butter of a translator’s job came from working on more functional texts like menus, packaging, or marketing copy. Now these tasks fall to automated systems, offered for free or at low cost by large tech companies. When faced with the choice between an expensive human and a cheap but inferior machine, the machine often wins.

Of course, machines are not really the players, let alone the winners, in this game. The real winners are those who own them, the tech companies that control the software and hardware platforms and have capital investments in server farms and model training and whose products can replace human labor. We can imagine a future in which the easiest way to acquire appropriate images is through a subscription to an AI model. This becomes a normal business cost, like the monthly charge to access Adobe Photoshop. The flow of money is thus redirected from freelance illustrators to those who own and operate the machines.

So, what can be done? Many have taken aim at the vast quantities of training data used to create AI systems, which now stretches into the billions of images, far outstripping the 15,000 oil portraits used to produce Edmond de Belamy. This data is almost universally obtained from freely available images on the web, under perhaps dubious interpretations of copyright laws. Some artists have demanded greater respect for copyright and the moral rights of creators. They suggest that images could be licensed under terms forbidding their use to train AI, or perhaps a set up where model users could pay artists for the images that contribute to a particular output.

These plans are morally satisfying but unlikely to have the desired effect of protecting the livelihoods of individual artists. In the past, strengthening copyright laws has universally benefited large media companies, and it is hard to see how this instance could be different. If AI models can only legally be trained on properly licensed images, then only those who own gargantuan image libraries will be able to train AI models. In practice, this would produce a monopoly for corporations like The Walt Disney Company that already control so much of our visual culture.

Even if artists could charge for the use of their work to train AI, we should not expect this to compensate for lost income. Much as music streaming platforms have decimated the incomes of musicians, the same cold logic applies here: If buyers are paying less for art, then the artists must also be paid less. The mediating presence of an AI system cannot change the basic balance of payments.

Yet some form of resistance is necessary if art is to remain a viable career for anyone but the wealthy. For many technologists, the questions around AI and art are abstract intellectual games about the philosophy of mind, or the nature of creativity and authorship. For working artists, however, they are concrete questions of tactics, of how to most effectively resist the forces that would destroy their sources of income.

There is a long tradition of workers resisting automation by attacking the machines that would replace them, dating back to the 19th century, when the Luddites, a secret society of weavers and textile workers, smashed the mechanised looms that turned them from skilled artisans to exploited factory workers. This tactic has merits; it can delay automation long enough to build solidarity and influence policy. But if artists are to use it effectively, they must recognize their common cause with others, like translators, checkout clerks, and truck drivers, whose livelihoods are also threatened by automation. And they must understand that their true foe is not the machine, but those who would wield it against them.

Special: Will AI destroy art? Or just change it?

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: AI, art, artificial intelligence

Topics: Artificial Intelligence, Disruptive Technologies

The arguments here equal the ‘deterrence’ arguments of pro nuclear monopoly policy promoted here. If AI makes movies, music, art, and politician’s speeches, if AI markets, brands, and decides who is in, who is out, if AI takes over nuclear codes and when and where to use them, if AI does a better job than corporate lawyers about crafting arguments and finding precedent ( already does), if AI can decide ‘sacrifice zones’, ‘acceptable losses’, how the masses will react when things are given or taken away, then we can hope that the 11% of the world involved in the Ukraine… Read more »

one way to head off AI art theft, but not a very good one, is to use watermarks on ones painting. sure it will take away from aesthetics of your work but with watermarks covering your work would make it harder for AI to steal it

That does not work. Some AIs have learned from images from watermarks and replicate the watermarks when generating images.

“If AI kills art, it will join an illustrious club that includes movements like realism, impressionism, and abstraction, and other media such as film and photography. In truth, the art world thrives on supposed art killers.” – this doesn’t make any sense. Any “movement” in art was just art in another form. While it’s true that photography or film were a threat for painters, it’s nowhere near the way that AI is a threat for the art now. AI means automation, it means achieving results much faster, while not really working and not being the only author of your work.… Read more »