Poll: Americans, Japanese, and South Koreans don’t support using nuclear weapons against North Korea

By David M. Allison, Stephen Herzog | October 25, 2022

North Korea launches a suspected intercontinental ballistic missile reported to be a Hwasong-17, its largest-known ICBM, on May 25 (Seoul time), 2022 (Image YTN & YTN plus).

North Korea launches a suspected intercontinental ballistic missile reported to be a Hwasong-17, its largest-known ICBM, on May 25 (Seoul time), 2022 (Image YTN & YTN plus).

For months, evidence has accumulated that North Korea may be preparing its seventh nuclear explosive test. Continuous warnings by analysts and the media about this possibility are a sobering reminder that Pyongyang’s continued pursuit of a larger nuclear arsenal remains a challenge for the Non-Proliferation Treaty and the nonproliferation regime. This continues to be the case even as the public and leaders around the world have largely shifted their attention to the nuclear dimensions of the war in Ukraine.

Resumption of nuclear activity on the Korean Peninsula is hardly a work of speculative fiction. In December 2019, North Korean Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un announced an end to his self-imposed nuclear testing moratorium. Alongside this rhetoric, satellite imagery analysts now believe the tunnels at the Punggye-ri Nuclear Test Site were never actually destroyed in the lead-up to the Singapore Summit. Moreover, there are several reasons to believe that North Korea, which has tested six nuclear devices since 2006 and over a dozen ballistic missiles in the last month alone, may be considering a new nuclear test. These include signaling the regime’s resolve to retain a nuclear arsenal, increasing its bargaining leverage with adversaries, and more tangibly, improving its capabilities to field deliverable nuclear weapons.

A North Korean test will almost inevitably draw a response from the United States and the two most likely targets of future aggression by Pyongyang: Japan and South Korea. Such a response would likely entail increased defense cooperation, joint military exercises, and reaffirmed alliance commitments. Washington has already provided security guarantees to its East Asian allies by extending its nuclear umbrella. This has included the so-called “tripwire” deployments of large contingents of US troops to Japan and South Korea. Yet, longstanding concerns that became prominent during the Trump administration about US willingness to defend these allies remain. Hoping to avoid the fate of Ukraine, some South Korean politicians have even increased their calls for indigenous nuclear proliferation to deter an invasion by the North. At the same time, the administrations of Joe Biden, Fumio Kushida, and Yoon Suk-yeol have all been clear about the ironclad nature of US nuclear umbrella pledges.

Regardless of what seems like an elite consensus on the nuclear umbrella, it’s not clear that the US, Japanese, and South Korean populations would actually support the retaliatory strikes underpinning it. Americans have shown increasing skepticism of international commitments in recent years. Polling shows a majority of Japanese support nuclear disarmament and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), a legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. South Koreans may reject any nuclear use on the Korean Peninsula because it would have major human and environmental consequences for their homeland.

Nuclear crises, extended deterrence, and public opinion. Together with our colleague Jiyoung Ko, we investigated the potential disconnect between public and elite views on extended deterrence vis-à-vis North Korea. Our new survey research, recently published in the Journal of Conflict Resolution, speaks directly to this question.

We collected responses from 6,623 American, Japanese, and South Korean adults in an internet survey setting during a period of high tension with North Korea in 2018. The key demographics of our samples matched those of each respective country, allowing us to make inferences about the views of these national populations.

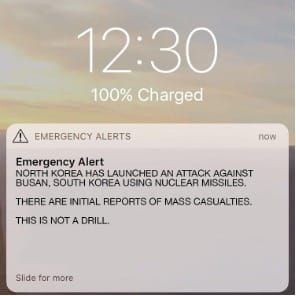

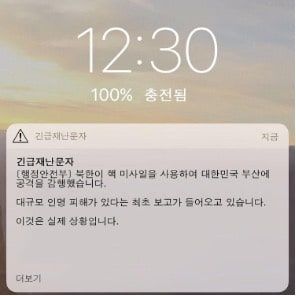

We asked participants—in English, Japanese, or Korean—how the United States should respond to hypothetical scenarios in which North Korea attacked Japan or South Korea. Then we showed them realistic emergency alert messages about a North Korean attack, modeled on the formats actually used by their governments. To determine how certain features of the attack affected preferences for retaliation, we randomly assigned respondents to different crisis scenarios. While all participants were informed of a North Korean attack on a civilian target, we varied:

- Whether the attack targeted Japan or South Korea;

- Whether the attack used conventional or nuclear weapons; and

- Whether or not US troops were among the casualties.

Simulated emergency alert messages

After the survey takers viewed an emergency alert message, we asked them about potential US responses. First, they were asked to select their preferred response(s) from a list of non-military and military options ranging from doing nothing to nuclear retaliation. The list included a realistic set of possible nuclear, conventional, and diplomatic responses to a North Korean attack. Then, we asked respondents to explain their choices before asking whether they would support nuclear use presented as a fait accompli: a US presidential decision to launch a nuclear strike against the Kim regime.

Low cross-national support for nuclear weapon use. Our central finding was extremely limited public support in all three countries for the use of nuclear weapons against North Korea. This result is durable regardless of whether North Korea attacks with nuclear or conventional missiles, strikes Japan or South Korea, kills forward-deployed US troops, or threatens subjects’ homelands.

Previous survey-based studies have suggested much higher levels of support among Americans for nuclear strikes. But these studies simulated conflicts between the United States and non-nuclear adversaries, scenarios where nuclear use is unlikely to be considered. By contrast, our study of a North Korean nuclear crisis under the shadow of the nuclear umbrella represents a most-likely case for US nuclear strikes. It also introduces the retaliatory dynamics present in any conflict with a nuclear-armed adversary.

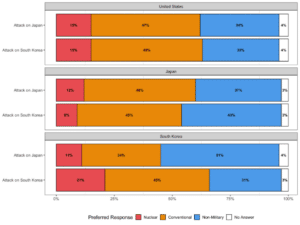

Publics’ preferred responses to a North Korean attack

As our data show, members of the public who prefer a nuclear response to a North Korean attack represent a small minority of Americans, Japanese, and South Koreans. We do find that a North Korean first-use of nuclear weapons and a US presidential order for a nuclear response both increase support for the nuclear option. However, even in these scenarios, backing for the retaliatory strikes underpinning Washington’s nuclear umbrella remains low.

This is not to say that affected publics would take a pacifist approach to North Korean escalation beyond its oftentimes harsh rhetoric. Previous polling published in the Bulletin indicated that a majority of Americans prefer a non-military solution to Pyongyang’s testing of nuclear-capable missiles. Our work suggests that actual missile attacks on US allies would generate majority support for military action. As the graph shows, support for conventional military operations against North Korea is high. But one thing is clear: The overwhelming preference among the three publics is to avoid nuclear retaliation.

We asked respondents to select from 10 possible reasons why they preferred nuclear restraint. Fear of nuclear escalation and the belief that nuclear use is abhorrent were the most frequently cited. In the United States (60 percent) and South Korea (59 percent), the most prominent concern was fear of nuclear escalation. Among Japanese citizens (53 percent), this was the second most selected answer. The most common rationale in Japan (58 percent) was the nuclear taboo, the belief that no country should ever use nuclear weapons. This was the second most pervasive explanation in the United States (44 percent) and South Korea (51 percent).

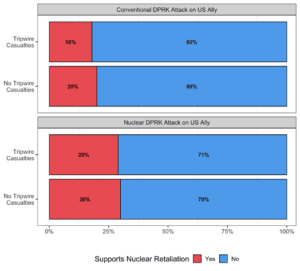

We found no evidence that casualties among US troops placed as “tripwires” in Japan and South Korea increase American public support for nuclear retaliation against North Korea. Our research tested whether the US public would support a nuclear response after the president has ordered a nuclear strike. Presenting the strike as a fait accompli increased public support relative to respondents’ independent preferences, but an overwhelming majority of Americans still reject nuclear use. This holds true even when the scenario specifically mentioned US military casualties. Taking the poll’s margin of error into account, US troop deaths at the hands of the Kim regime do not statistically increase American public support for nuclear retaliation. Our finding thus calls into question the tripwire component of decades of US overseas basing strategies.

Tripwire casualties and US support for nuclear use after a presidential strike order

Policy implications. The North Korean nuclear threat is unlikely to dissipate in the near-term future. A seventh North Korean test may unfortunately occur in the coming weeks or months. Likewise, there appears to be no end in sight for the debate over whether Washington would—or should—live up to the retaliatory commitments of its nuclear umbrella. These discussions are hardly new, but decades-old theories of deterrence require rethinking in today’s world of complex threats and alliances. Our finding of universally low public support for nuclear retaliation in response to an unprovoked North Korean attack on a civilian target should make American, Japanese, and South Korean officials pause for reflection.

Reassuringly, our results suggest leaders should not fear strong public pressure to use nuclear weapons in an escalating crisis during which North Korea attacks a US ally. While publics prefer responses that include a conventional military component, avoiding escalation to nuclear war is a majority preference in all three countries. On the other hand, the inability of US military casualties to increase American public support for a nuclear response risks undermining long-held beliefs about using tripwires to reassure allies. As we concluded in our study: “Like the overall policy of extended nuclear deterrence it intends to bolster, the tripwire is a product of decades of elite consensus that may require reevaluation.”

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.