March 6, 2023

Can a 1975 bioweapons ban handle today’s biothreats?

Rapid advances in biotechnology and the lack of an enforcement mechanism are challenging the Biological Weapons Convention. Amid swirling allegations that countries are violating the treaty, are slow-moving attempts to update it enough to prevent biological doom?

By

Design by

Digitally-colorized electron microscopic image of an isolate of Ebola virus. (CDC, Frederick Murphy)

Can a 1975 bioweapons ban handle today’s biothreats?

Rapid advances in biotechnology and the lack of an enforcement mechanism are challenging the Biological Weapons Convention. Amid swirling allegations that countries are violating the treaty, are slow-moving attempts to update it enough to prevent biological doom?

March 2, 2023

By Matt Field

Design by Erik English

Matthew Meselson is a true eminence grise of arms control in the realm of biological weaponry. In 1984, he traveled to Thailand to debunk the US assertion that forces backed by the Soviet Union were using “toxin warfare” on Hmong and Cambodian Khmer Rouge fighters in Southeast Asia. The alleged “poison from the sky” was actually bee poop, he concluded, after witnessing a several-minute “shower of feces” from high flying honeybees near Chiang Mai. Later in the 1990s, he and his wife, the noted bioweapons scholar Jeanne Guillemin, and colleagues investigated an anthrax outbreak that occurred in 1979 in Sverdlovsk, Russia. An incident at a bioweapons facility had lofted spores into the air, their study showed.

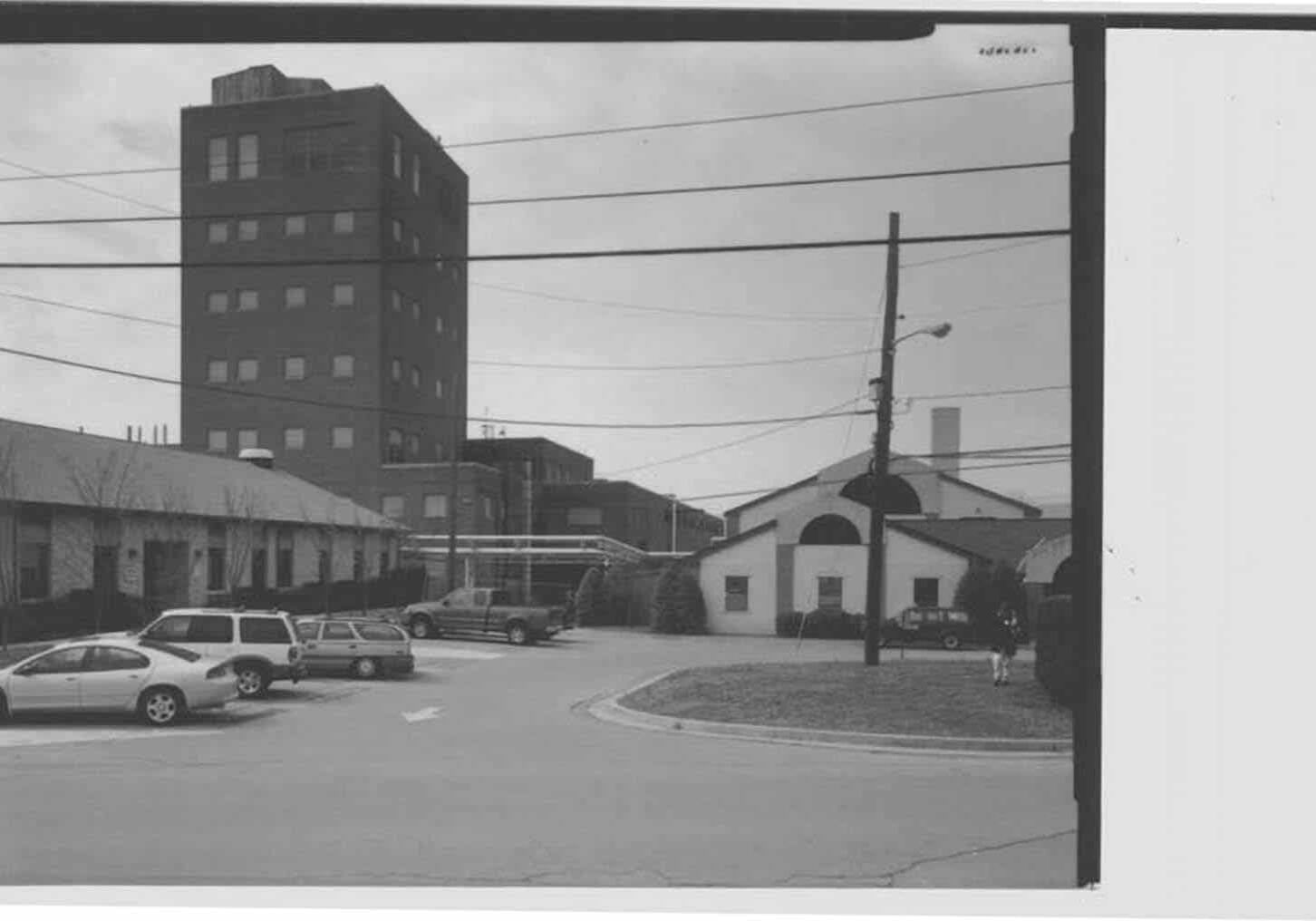

Early in his career, as Meselson recounted in a recent interview, a “very nice” former Harvard immunology professor gave him a tour of Fort Detrick, the Maryland military base that was the center of the United States’ biological weapons program.

“We came to a big building seven stories high. And it looked from a distance as though it had real windows, but when you get up close, you can see they’re not real windows at all. There were no windows.”

Meselson thought: “Well, what do we do in there?”

Indeed, the structure, a rectangular industrial affair had no windows. Instead, glass bricks let in light while obscuring the project underway inside. This was Building 470, where the United States housed 30-foot-tall fermentation tanks for churning out anthrax.

Also on the Fort Detrick campus was the “Eight Ball,” a multi-story spherical building that looks sort of like Disney’s Epcot Center in Florida, except the air-tight chamber was used for testing biowarfare agents. Meselson’s guide told him biological weapons “could save us a lot of money” compared to nuclear weapons; this was the budget option for killing on a huge scale.

The one-million-liter test sphere in Frederick, Maryland.

“It didn't take me long to realize, ‘Hey wait, first of all, we got a lot of money,’” Meselson recalled. “And second, ‘Why would we pioneer a strategic weapon that could wipe out whole cities that’s cheap?’”

Negotiating the BWC more than half a century ago. (UN Office for Disarmament Affairs)

A toothless treaty?

Since 1975, the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) has been the cornerstone of international efforts to curb the proliferation of offensive biological weapons programs. Many experts credit the treaty with having established or at least reinforced a “norm” against the use of germs as weapons. But there’s always been a piece missing from the bioweapons ban. The convention has no strict verification regime to ensure that countries are complying with it. Unlike the Chemical Weapons Convention or the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, no corps of inspectors travels the world to confirm treaty compliance. A plan to have some sort of inspection program fell through two decades ago, when the United States, responding to concerns from its pharmaceutical companies and to misgivings about the feasibility of inspecting potentially tens of thousands of sites, killed the negotiations on such an oversight body.

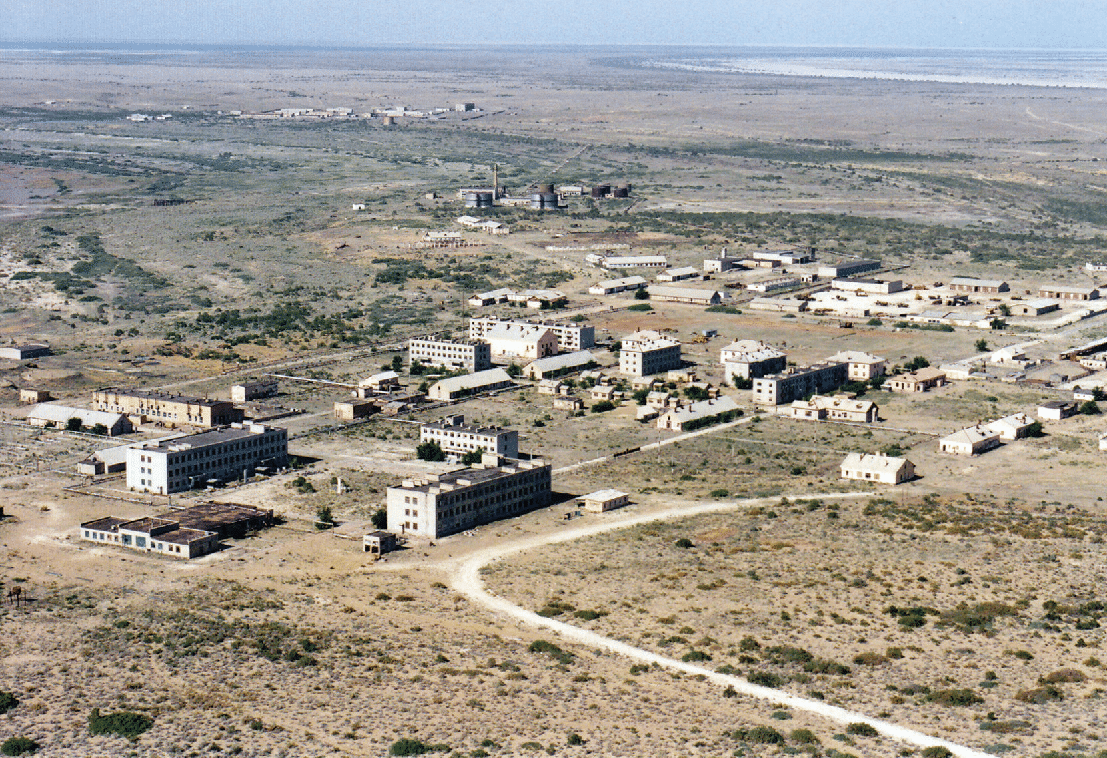

And there have been dead-to-rights violators of the BWC in the past. After becoming one of the original signers of the treaty, the Soviet Union undertook to create an illicit program of astounding size and ambition. A military program along with a supposed civilian enterprise called Biopreparat employed tens of thousands of workers who produced or researched anthrax, smallpox, and other diseases in a far-flung network of facilities. The scientists and technicians worked on sci-fi-like horrors like “chimeric viruses that would cause two diseases either nearly simultaneously or successively,” according to an exhaustive history of the Soviet program by Milton Leitenberg and Raymond A. Zalinskas. After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Russian government admitted to inheriting the secret program and pledged to end it, but a lack of transparency surrounding key military sites and the government’s subsequent efforts to backtrack on its admissions have led to persistent doubts about whether the Soviet program was ever truly dismantled.

After years of inaction on the verification issue, there was modest movement at the bioweapons treaty’s Ninth Review Conference in Geneva in December. Delegates cracked the door open to a formal verification process by setting up a working group to explore the issue. But against the backdrop of rapid advances in biotechnology and the new risks they create—not to mention swirling allegations that countries still have bioweapons programs—a key question remains: Can the existing biological arms control treaty live up to the promise of a world free from biowarfare?

Bioweapons before the BWC

Bioweapons before the BWC

By the time Meselson began researching America’s offensive weapons program in 1963, he was, though young, already a scientific star who had shown how DNA replicated and had helped show how messenger RNA brought the genetic instructions encoded in DNA to the cellular machinery for protein synthesis. He’d gone to Washington that summer after a divorce because “I thought it’d be fun and I might meet somebody I like, a lady.”

The now defunct Arms Control and Disarmament Agency (then independent but now merged with the State Department) had hired Meselson to ponder European theater nuclear weapons. But the molecular biologist soon discovered he was swimming in crowded waters. Giants of the nuclear intelligentsia, like the ambassador to the Soviet Union, “came to me,” Meselson recalled. It was embarrassing.

“People had already thought about this, but not just people: Henry Kissinger had written a book called The Necessity for Choice all about this. So how am I going to come up with anything useful in a few weeks in the summertime?” Meselson remembered thinking.

He asked, and the agency agreed, to transfer him to deal with chemical and biological weapons, an area more suited to his expertise, at least.

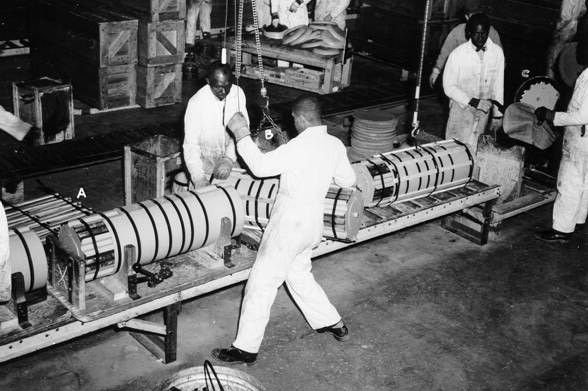

At Fort Detrick in 1963, Meselson caught only a glimpse of just a part of America’s vast biological weapons program. At the Pine Bluff Arsenal in Arkansas, workers loaded bioweapons agents onto bombs and into spray tanks. The facility handled dried anthrax bacteria, tularemia bacteria, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, and other pathogens in its biowarfare stockpiles, according to the late bioweapons expert Jonathan Tucker. Tens of thousands of loaded munitions were stored at the site. Near the weapons facilities, boy scouts held “camporees,” and hunters and fishermen wandered Pine Bluff’s 9,000 acres of woods—a “stone's throw from the Western world's deadliest collection of germs,” a 1971 New York Times story reported.

Meanwhile, out in the Utah desert at the Dugway Proving Ground, the military ran open-air tests using viruses and bacteria in addition to chemical weapons. The experiments didn’t always stay on the range. Thousands of sheep died in 1968 after a malfunction caused a plane carrying nerve agent to release it at a higher altitude than planned, contaminating grazing lands 27 miles away. According to a 1994 US Senate staff report, investigations also found that animals near Dugway had antigens to Venezuelan equine encephalomyelitis, suggesting they had been exposed due to work at Dugway. The disease had previously only been found among rats in Florida.

The latter testing mishap was likely a result of a basic truth about bioweapons: They are extremely tricky for militaries to handle. Environmental factors like UV radiation can affect pathogens. The wind can blow them off course. A contagious disease could boomerang, infecting whoever deploys it, or it could mutate after its release. Despite these obvious drawbacks, biological weapons are likely quite capable of killing or sickening a lot of people. In 1970, the World Health Organization estimated that 110 pounds of tularemia bacteria, if aerosolized and dispersed on a city of five million people, would kill 19,000 and sicken another 250,000. Indeed, the accidental release from the Sverdlovsk anthrax plant in the Soviet Union killed more than 60 people downwind from the facility in 1979.

While few countries have used bioweapons in war, several, have maintained programs. During World War II, the Japanese Imperial Army tested and used pathogen weapons on a large scale. Planes flew over China dropping bombs full of plague-infested fleas. Though crude, the attacks sparked reports of outbreaks, according to The New York Times in 1995. Japanese medical staff in China would conduct vivisections, sometimes without anesthetics, to see how biological agents affected patients. As one wartime medic with the army’s notorious Unit 731 told the Times, anesthetics “might have an effect on the results.” A former Japanese military doctor later recounted sending samples of typhoid germs to Japanese troops. The test tubes, the doctor was told, would be used to poison wells.

By the time Meselson began researching America’s offensive weapons program in 1963, he was, though young, already a scientific star who had shown how DNA replicated and had helped show how messenger RNA brought the genetic instructions encoded in DNA to the cellular machinery for protein synthesis. He’d gone to Washington that summer after a divorce because “I thought it’d be fun and I might meet somebody I like, a lady.”

The now defunct Arms Control and Disarmament Agency (then independent but now merged with the State Department) had hired Meselson to ponder European theater nuclear weapons. But the molecular biologist soon discovered he was swimming in crowded waters. Giants of the nuclear intelligentsia, like the ambassador to the Soviet Union, “came to me,” Meselson recalled. It was embarrassing.

“People had already thought about this, but not just people: Henry Kissinger had written a book called The Necessity for Choice all about this. So how am I going to come up with anything useful in a few weeks in the summertime?” Meselson remembers thinking.

He asked, and the agency agreed, to transfer him to deal with chemical and biological weapons, an area more suited to his expertise, at least.

At Fort Detrick in 1963, Meselson caught only a glimpse of just a part of America’s vast biological weapons program.

Earlier, during World War I, Germany attempted to infect animals with disease in various countries as a form of sabotage, but the Japanese program certainly stands alone in scale.

The scarcity of examples of use, however, belies the apparent interest countries have displayed in biological weapons. A 2017 article in The Nonproliferation Review by biological weapons expert W. Seth Carus notes that "[c]ollecting information on biological-weapon programs is difficult, even for intelligence organizations, and there is limited information available on the extent and character of past programs. A review of the open-source literature supports claims that twenty-three states had, probably had, or possibly had a program. The number of active programs has varied over time, from a low of zero in 1920 to a high of possibly as many as eight in 1990." A 2008 chart by the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies lists 23 countries as having had programs that researched bioweapons agents.

Though Meselson thought his argument about the folly of pioneering cheaper weapons of mass destruction was solid, he had a realization: He would have to influence people both inside and outside of government. Meselson talked about biological weapons whenever he could—to members of Congress, staff in the executive branch, and TV hosts. Though the United States was spending tens of millions of dollars a year on the weapons during the 1950s and ‘60s—Sonia Ben Ouagrham-Gormley, a researcher at George Mason University, wrote the government spent $700 million over the life the program—the public wasn’t fixated on them the way it was on the nuclear threat. “Everybody talks about nuclear weapons. There's only this Meselson guy from Harvard who's talking about biological weapons … and the people who disagree with him,” Meselson said of his early work.

Following the disastrous nerve agent incident at Dugway, Congress put pressure on the Nixon administration to reign in America’s chemical and biological warfare efforts, including through consideration of a test ban. In November 1969, however, President Richard Nixon, officially ended the country’s offensive bioweapons program “Mankind already carries in its own hands too many of the seeds of its own destruction,” he wrote in a statement that also limited the chemical weapons program. The president ordered the destruction of the country’s bioweapons and embraced a draft treaty to ban them, which would eventually become the BWC.

A dual-use chlorine plant being monitored by the UN Special Commission in Iraq. (UN Photo)

Verification on the move

Verification on the move

Two developments in the 1990s pushed BWC members to attempt to give the treaty more teeth. In February 1991, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein faced a Sword of Damocles moment. Iraq had invaded and quickly conquered Kuwait in August 1990, but after a roughly six-week military campaign, a US-led coalition pushed Iraqi forces out of Kuwait and a portion of southern Iraq. In exchange for a ceasefire, Saddam agreed to an invasive UN-led inspection of his country’s nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons programs. For, about eight years, the UN Special Commission (UNSCOM) visited sites, interviewed officials, and audited supplies of material with weapons applications, like bacterial growth media. As if in a spy thriller, UNSCOM investigators raced to visit sites before minders could alert interview targets. They played hardball. During one standoff outside a Baghdad veterinary school in 1993, an inspector remembered calling his boss for advice. “Tell them you will end your mission, depart Iraq, and they can deal with the Security Council,” the boss said. As the inspectors began to drive off, the Iraqis chased after them to invite in the team.

A month before BWC negotiators met in September 1991 for the third treaty review conference, Iraq acknowledged it had a biological weapons program, claiming it was for defensive purposes. In fact, by start of the Persian Gulf War, Saddam had scores of missiles and bombs loaded with anthrax and biological toxins. At around the same time that the Iraqi weapons saga was playing out, in another corner of the world, Soviet defectors were revealing a picture of their country’s illicit bioweapons effort. High-ranking scientists Vladimir Pasechnik and Ken Alibek, who defected to the United Kingdom and the United States in 1989 and 1992, respectively, shared alarming details about the size and ambitions of Biopreparat.

The two programs seemed to be proof positive that countries had been harboring bioweapons secrets. What might other countries be hiding? In the 1991 review conference’s final document, BWC members agreed to create a group of experts to examine how to verify compliance with the convention.

The group, known by the mashup VEREX (an acronym combining “verification” with “experts”) reported on 21 methods for assessing treaty compliance. These ranged from checking declarations about biological programs that countries could submit to stationing personnel at specific sites. Some ideas would be costly. Others posed a variety of other problems. Requiring declarations of biological manufacturing facilities, for example, would rely on the honesty and exhaustiveness of a self-interested state; few if any countries would admit to breaking the rules.

But some proposals, in combination, might be able to ascertain compliance.

To build on the expert verification report, BWC members created the so-called “Ad Hoc Group” in 1994; it was to negotiate over a verification system, called a protocol. Although the group met 24 times over the course of six years, negotiators could never coalesce around a verification mechanism. A rolling text of the proposal contained more than 1,000 brackets denoting places where there was no agreement.

In July 2001, the relatively new George W. Bush administration told the Ad Hoc Group that the years long discussions had been a bust. The talks were over.

The emerging protocol would have had countries declare some biodefense, vaccine, and other research facilities relevant to bioweapons development, subjecting them to potential inspection. But countries would not need to declare a vast number of facilities that could also play a role in illicit weapons programs, like some pharmaceutical plants, according to a New York Times article from 2001. Inspectors would therefore be able to visit just a relatively small sample of the potentially tens of thousands of facilities relevant to the treaty, Donald Mahley, a US negotiator, told the Ad Hoc Group. As negotiators crafted the verification proposal, they erroneously looked towards treaties like the Chemical Weapons Convention, which bans chemical weapons, Mahley said. For economic reasons, however, chemical weapons precursors, which also have peaceful applications, are produced in “a limited number of facilities,” Mahley said. Chemical weapons development therefore is easier to monitor

In the view of the United States, the Ad Hoc Group proposal would expose sensitive information while failing to deter treaty violators.

“It will not enhance our confidence in compliance and will do little to deter those countries seeking to develop biological weapons. In our assessment, the draft Protocol would put national security and confidential business information at risk,” Mahley said in Geneva.

Critics in other countries roundly scorned the United States for abruptly ending the verification negotiations. Several countries have kept up the push ever since.

According to Andrew Weber, who worked to dismantle the Soviet bioweapons empire as part of the Pentagon’s Cooperative Threat Reduction program, the George W. Bush administration had an ideological problem with the BWC verification negotiations. John Bolton, a top arms control official in the administration “who's famously against all arms control, helped blow up the work that was done on a verification protocol,” Weber, now a senior fellow at the Council on Strategic Risks, told me. “The politics are much different today.”

Wanting

more

A German soldier on a crane during a chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear defense demonstration. (NATO, Flickr)

Wanting more

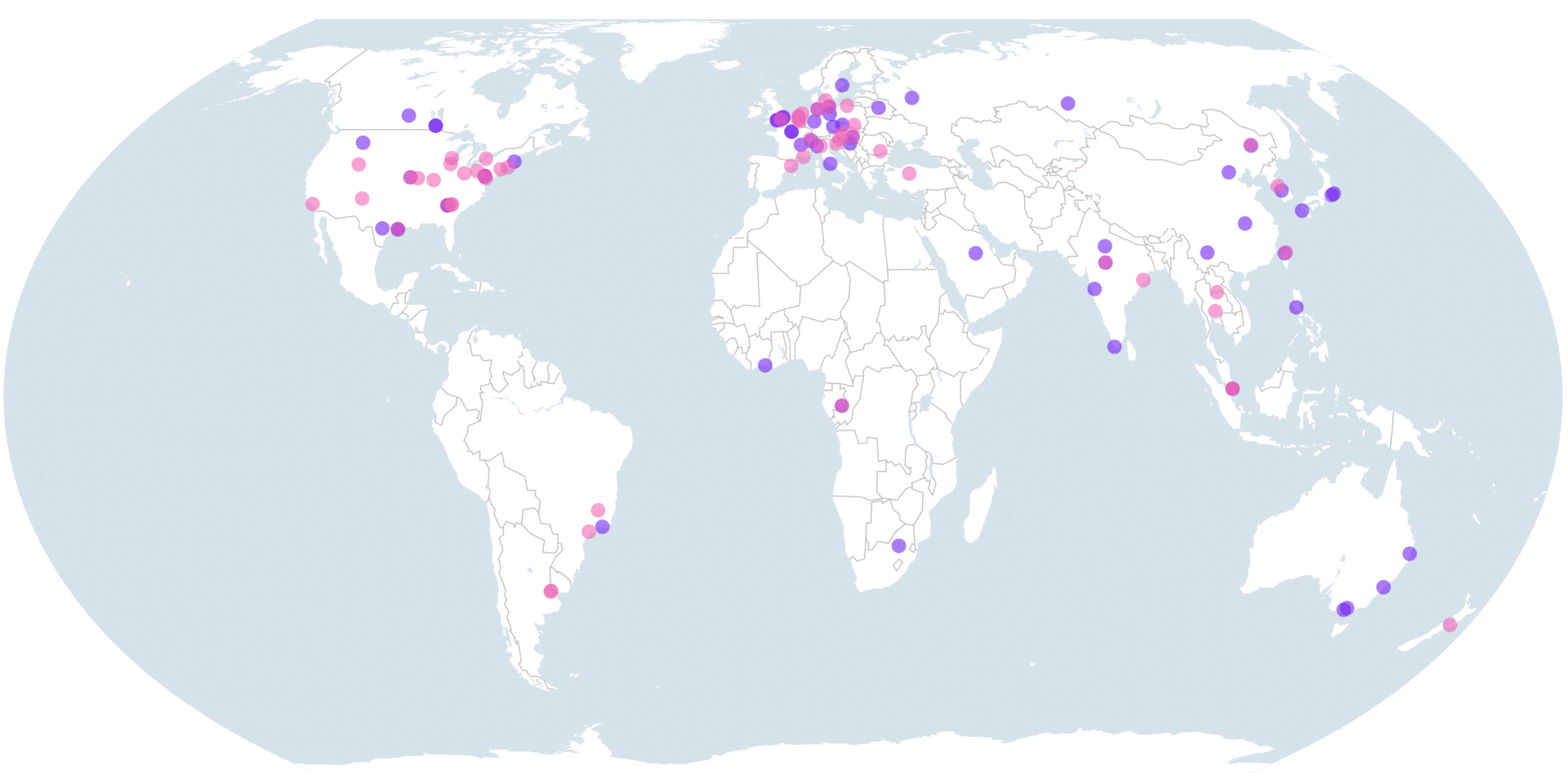

Over the years, BWC countries and civil society groups have worked to increase the transparency of biodefense and dual-use biological research activities. In 1987, the convention implemented a system of self-reporting known officially as Confidence-Building Measures. Using a form, countries submit information about research centers, biodefense programs, disease outbreaks, and other issues pertinent to biological arms control. France proposed the concept of “peer review” compliance assessments, whereby other countries could review how well a country is adhering to the BWC through visits and other means. More recently, Filippa Lentzos and Gregory Koblentz, biosecurity experts at King’s College London and George Mason University, respectively, produced a system for tracking the proliferation of the BSL-4 and BSL-3+ labs where researchers conduct dual-use research on dangerous pathogens like Ebola or smallpox virus.

James Revill, the head of the weapons of mass destruction program at United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR), an autonomous research institute within the UN, said the goal of a verification system for the BWC would not be a 100-percent guarantee that no one is violating the treaty; the goal should be to increase confidence that no country is doing so. That’s been the thrust of the Confidence-Building Measures and other efforts to boost BWC transparency, of which there will likely be more in the future.

Map of current BSL-4 and BSL-3+ labs around the world

Biosafety Level 4 labs

Biosafety Level 3+ labs

Meanwhile, biological attacks have been few and far between since 2001. That’s when a disaffected US Army researcher allegedly stole anthrax from a biodefense lab and sent tainted mail to politicians and media figures. And Unit 731’s atrocities and the major offensive bioweapons programs of the Cold War are even further in the rearview mirror. So is the bioweapons treaty working as is, or does it need a more concrete verification mechanism, like other weapons treaties?

A verification arm of the BWC could be useful in sorting out allegations about biological weapons—and debunking disinformation campaigns that involve bioweapons allegations.

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine materialized, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s government and its media proxies waged a massive public relations campaign aimed at convincing people that a network of labs in Ukraine with links to the US military’s Biological Threat Reduction Program was part of a US-Ukraine bioweapons program. The US and Ukrainian governments—and many outside experts—insist that the labs are public and animal health facilities, and that the Russian PR campaign is false propaganda.

Indeed, many of the allegations about the labs have been easily and widely debunked. Media figures like Dilyana Gaytandzhieva, a Bulgarian journalist, cherry picked from legal documents to paint a picture of Ukrainian and American malfeasance. And the Russian propaganda campaign drew from clearly selective readings of data presented at public symposia and in published reports to claim it had evidence of an offensive program.

As fact-free as it appears to be, the Russian campaign spread ably in the early days of the Ukraine war; it even found a receptive audience among right-wing outlets and QAnon adherents in the United States.

But all bioweapons allegations aren’t as easily debunked as the Kremlin’s claims. The United States currently accuses Russia and North Korea of maintaining offensive bioweapons capabilities, and it’s expressed worries about other countries, including Iran and China. “The public record strongly suggests that Russia has maintained and modernized the surviving parts of the Soviet biological weapons program,” Robert Petersen, an analyst for the Danish Centre for Biosecurity and Biopreparedness, wrote in a piece in the Bulletin last year.

The claims highlight the lack of a verification mechanism in the BWC. An independent, official system could, at least theoretically, arrive at definitive resolutions of allegations. “Whatever the real intention or veracity of Russian allegations, they underline the value of functioning clarification and compliance mechanisms in the BWC,” a 2022 UNIDIR report on verification said.

What Revill said was a shift came in November 2021. Under the Biden administration, Ambassador Bonnie Denise Jenkins, the top US official for arms control, nudged the door open a bit on the BWC verification issue. In a speech before BWC members, she called for an expert working group that would explore methods to strengthen the agreement, including measures that would “enhance assurance of compliance.”

At last year’s Ninth Review Conference, Jenkins doubled down: “We need to examine how technology has changed and what the bioweapons threats of today and tomorrow looks like. We also need to explore what measures—yes, including possible verification measures—might be effective in today’s context,” she said.

Although modest, observers say BWC delegates made a breakthrough in December, agreeing to form the working group that will examine verification and other issues.

Falling behind

on science

Navy photographer Mike Pendergrass practices donning a gas mask during a US Navy field training. (US Navy, Wikimedia Commons)

Falling behind on science

The drafters of the BWC had one particularly strong insight: It would be difficult to predict what exactly might constitute a biowarfare agent in the future. They also knew that few if any biological agents had no peaceful purpose whatsoever. It’s important, for example, that scientists have access to even the deadliest viruses if they are to develop vaccines against them. In addition to banning delivery systems for bioweapons, the first article of the convention, known as the general purpose criterion, simply requires that countries don’t “develop, produce, stockpile or otherwise acquire or retain” biological agents such as microbes or toxins (usually chemicals produced by organisms) “of types and in quantities that have no justification for prophylactic, protective or other peaceful purposes.” Experts say this provision future-proofs the convention.

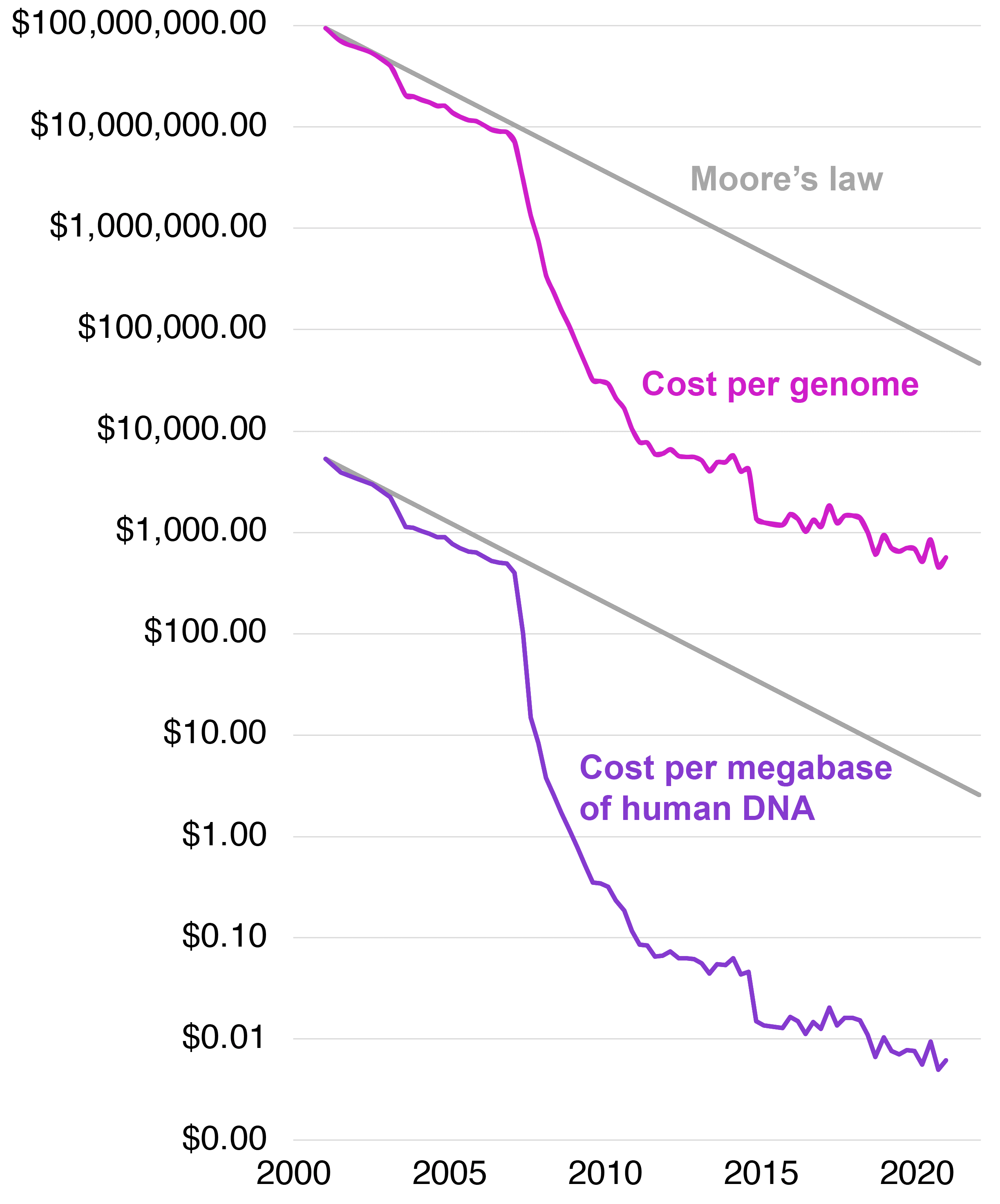

Science hasn’t stood still since the convention went into effect in 1975, and it hasn’t taken a pause since the verification talks failed to gain traction 20 years ago. The human genome was mostly decoded by 2003. Now many companies have moved past “reading” genes to “writing” or synthesizing them. Researchers could soon have gene synthesis technology at their desks. New CRISPR gene editing technology is making it easier to accurately insert genes into genomes. And beyond progress in genetic engineering, AI-based systems can now churn out the recipes for novel proteins and toxic chemicals. In terms of bioweapons delivery devices, uncrewed aerial vehicles are becoming increasingly capable.

And some new knowledge is opening doors to misuses of biology-related technology that might not be covered by the convention. Lentzos, the King’s College London expert, pointed to areas such as surveillance technology that can track gait and other physical characteristics as even more of a concern to her than new biological weapons. These technologies “should be classified as ways of using biology to cause harm,” she said, but they wouldn’t fall under the purview of the BWC.

The declining cost of DNA sequencing (logarithmic scale)

“It’s now easier to make pathogens, find pathogens, [or] tweak pathogens, but it's essentially the same logic of: What is a biological weapon?” Lentzos said. “[The technology is] more readily accessible to a larger number of people, we can produce them quicker and tweak them, but it's the same sort of logic. Where my bigger concern is, is in these other ways of using biology to suppress and surveil people.”

To deal with how advances in science and technology might impact the BWC, the original convention text called for members to meet in Geneva five years after enacting the treaty. The conferences have continued almost every five years since. At them, treaty members have gradually included so-called “additional understandings” and an article-by-article review section in final conference documents.

But BWC members have fallen off in explicitly describing the science and technology developments that could affect the treaty. A BWC review conference hasn’t had a solid article-by-article review since 2011. In 2016, delegates essentially copied and pasted from the previous review conference, adding very little in the way of additional understandings. Last December, states didn’t include the article-by-article review section at all and didn’t even bother to rehash a previous version. One result of this neglect: The final document from the December conference doesn’t include language that specifies that gene-edited agents could also be bioweapons, something the United States hoped to include. (Given the generalized definition of what is prohibited under a convention meant to encapsulate current and future threats, it’s debatable whether any specific technology needs to be mentioned in additional understandings; nonetheless, over the years BWC delegates have specified, for example, that the convention applies even to artificially created biological agents.)

“It is worrisome that states parties can't agree on relatively simple propositions that would ensure that the Article 1 prohibition on developing biological weapons includes biological agents produced or modified via emerging technologies such as genome editing,” Koblentz, the George Mason University biosecurity expert, said.

As with the verification issue, however, the latest review conference managed to push another door open, too, seeking to achieve a long-held goal: a science and technology review mechanism. The working group that will consider verification will also weigh how to develop a formalized system to keep the convention up to date on science and technology.

Micrograph photo of mild meningitis and hemorrhage in a fatal case of human anthrax. (CDC, Marshall Fox)

Along with risks, opportunity

Along with risks, opportunity

While advances in science and technology and other trends create potential risks, they also come with opportunities to improve compliance with the BWC.

Some of the verification proposals that the VEREX group made in the 1990s could be more effective today than they were then. Hundreds of satellites now circle Earth, meaning that the information one provides can be validated through redundancy. New types of sensors—for instance, those that can detect volatile organic compounds associated with bacterial growth—can enhance on-the-ground, but off-site assessments, according to the UNIDIR report on verification. And the internet makes it much easier to track academic studies, national legislation, and industrial statistics. “Since the 1990s, the science and technology of relevance to assessing compliance has significantly enhanced the potential of the 21 verification measures VEREX considered,” the report said.

Henrietta Wilson, a researcher at King’s College London who studies open-source research and its applicability to arms control, told me that access to data has skyrocketed in the decades since verification was originally considered. Now a researcher interested in weapons issues can comb through social media feeds, local media stories, government pronouncements, and more, with ease.

As Wilson sees the situation, the goal of open-source research, as it relates to the BWC, is to establish a baseline. Do researchers have LinkedIn profiles that have suddenly gone dark? That could mean something. Is certain equipment being ordered in excess of normal levels? Again, it’s a situation potentially worth digging into more deeply.

“What verification looks like in that context is less about finding the smoking gun of a violation and more about understanding what normal is and looking for aberrations from that normal,” Wilson said. “Some people call that red flag monitoring. You're kind of constantly looking at normal patterns of things. And then you might think, ‘Wow, that looks a bit strange.’ And you investigate further.”

Even if a beefed up BWC could better verify treaty compliance and identify violators, that may not change much. It might not be enough to settle allegations. Lentzos cited the example of Syrian chemical weapons attacks. While international investigations by the UN and OPCW concluded that the Syrian government had used chemical weapons, Syria’s ally Russia was able to veto a 2017 Security Council resolution to impose sanctions. The country was able to escape accountability then and, in fact, chemical attacks continued. Likewise with the output of any BWC verification mechanism, “at the end, the judgment will be a political judgment, not a scientific technical judgment,” Lentzos said.

At the Palais

At the Palais

The Swiss city of Geneva is known for a few things: its lake, chocolate, famously private Swiss banks, and international diplomacy. Some 32,000 diplomats and associated personnel work in the international civil sector of the city, according to the Swiss mission to the UN. The city is also the site of BWC review conferences, held at the Palais des Nations UN complex. The Palais, as it’s often called, is a massive collection of art deco buildings, completed in 1938. Sitting on a sprawling hilly campus on the shores of Lake Geneva, it is one of the world’s large diplomatic venues, hosting some 5,300 meetings a year.

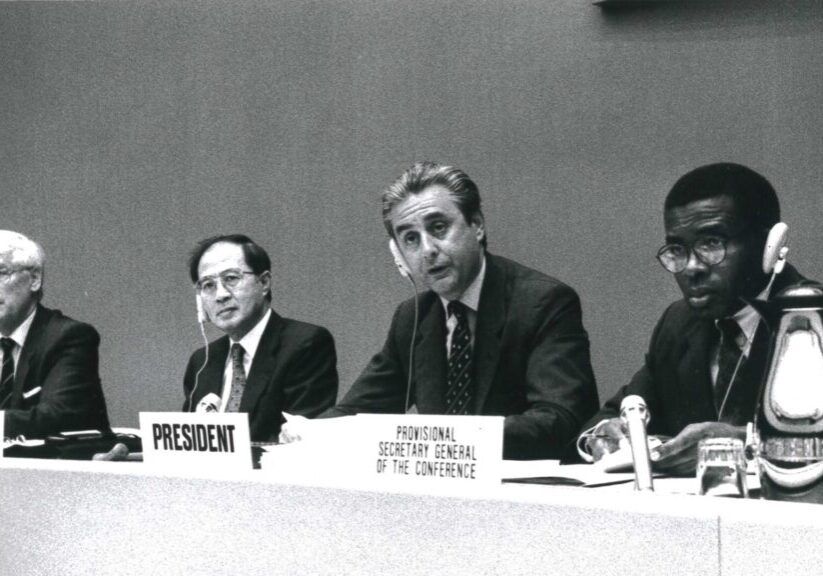

The three-week RevCon, as the abbreviation- and acronym-loving international diplomatic set calls such meetings, took place last December in a massive circular room at the Palais. Beneath a giant screen, the conference president, Leonardo Bencini of Italy, sat at a rostrum rising above a sea of desks that spread out toward the back the room, each with video screens, buttons for voting, and headphones for listening to simultaneous translations. The whole arrangement suggested that important business was being taken care of at the highest levels.

And the conference did tackle the weighty matter of biological disarmament with appropriate gravitas. UN Secretary General António Guterres beamed in on the large video screen behind the rostrum to urge on the conference delegates “The Biological Weapons Convention affirms the conscience of humankind,” Guterres said. “The COVID-19 pandemic brought the world to its knees. Now imagine a different kind of disease one that is most deliberately designed and can race though the global population even faster. Biological weapons are not the product of science fiction, they are a clear and present danger.”

But a review conference also has its housekeeping. The treaty members set meeting dates and decide when to have another review conference. They vote on whether to retain the three people hired to support the convention. Had things gone sideways at the end, which some feared might happen last year, the BWC could have lost its already bare-bones staff, at least until the next review sometime in Geneva before the end of 2027.

Until BWC members agreed to a slight expansion, Daniel Feakes, the chief of the Implementation Support Unit (ISU), held one of just three staff positions managing the day-to-day functioning of the treaty. After the conference, Feakes gained a single colleague. It wasn’t hard to believe him when he said the unit had been working 12-hour days during the review conference.

“We also have to support countries to implement the BWC,” Feakes told me. “And for a small team of people of only three, and, as you said, with 184 states parties and lots of demands and requests coming in—doing that with only three people is quite challenging, to say the least. Obviously.”

In comparison, about 500 people work at the OPCW, which had a roughly $76 million budget in 2021 and maintains a headquarters building at The Hague. And 2,500 people work at the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), which administers the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

The small staff of the BWC is partly a product of the treaty itself, which does not include a verification protocol. Verification would likely have required a larger permanent staff. As it is, the BWC billed its members less than $2 million for operations in 2021 and 2020. By the fourth day of the review conference, funds for having the UN audio visual operation broadcast the meetings live had run dry.

A large mural by Norwegian artist Per Lasson Krohg symbolizes the promise of future peace and individual freedom in the UN Security Council's meeting room. (j0e_m. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

What’s the point?

What’s the point?

With no legally binding way of ensuring countries are following the bioweapons rules and an outdated understanding of scientific and technological developments, is the BWC relevant? The threat of pandemics is on the rise, focusing attention on natural disease outbreaks. And other serious emerging risks—for instance, new tools for surveillance and oppression—rely on biological processes but may have nothing to do with the BWC.

A member of the UN Security Council investigative team in Iraq once said the comprehensive bioweapons verification effort in Iraq happened right at a “sweet spot,” as geopolitical tensions briefly thawed as the Soviet Union collapsed and the Cold War came to an end. These days world events regularly invite comparisons to the Cold War era; the sweet spot has long since soured. This year, for example, Ukraine’s delegation at the review conference railed against the Russian invasion and its violation of the “universal principles” that underpin the UN; Russia repeatedly short-circuited discussion of the war by invoking a review conference rule that limits debate to matters relevant to the treaty.

Against this backdrop, the consensus-driven process of decision-making in the BWC means that one country can grind progress to a halt.

Frustrating as the slow momentum is, the middle-aged BWC still has value. It’s carved out a space to discuss bioweapons and risks in the life sciences more broadly. Perhaps more importantly, it’s created a norm. Despite the BWC’s lack of a strong verification system and its other flaws, having countries get together every five years and publicly commit to not weaponize biology might be a powerful preventative.

"The international norm is so well established that currently no state will admit to having a biological weapons program because they don't want to be associated with any suggestion of development or use of biological weapons,” Revill said

Norms, however, aren’t written in stone.

Russian and North Korean agents have allegedly used chemicals several times in attempted and successful assassinations. The Syrian regime has used chemical weapons repeatedly. And Putin has made menacing threats about nuclear weapons—despite what some scholars have called a “nuclear taboo.” Under Putin, Russia is “increasingly trying to upend the entire UN system,” Weber, the former Pentagon official, said. The surge of bioweapons disinformation that came with the Ukraine war, could, some say, give the impression that biological weapons are acceptable.

Instead of concrete steps like creating a verification mechanism or a scientific and technical advisory process—or any other would-be critical element of a revitalized Biological Weapons Convention, the latest review conference simply formed a working group to consider these items. Modest though that result may seem—given that the search for agreement on a BWC enforcement mechanism has gone on for three decades—in today’s environment, some insiders contend it counts as significant. “You might say it’s no big deal,” Bencini, the conference president, told Arms Control Today, "but it is a big deal, actually, because we really had to break this deadlock so that we could still say that we do have a convention on biological weapons.”