A view from above of the Hyatt-Regency Hotel in downtown Indianapolis, site of this year's National Radiological Emergency Preparedness conference. (Photos by Thomas Gaulkin)

“Right of boom” :

Meet the experts who respond to nuclear disaster

May 25, 2023

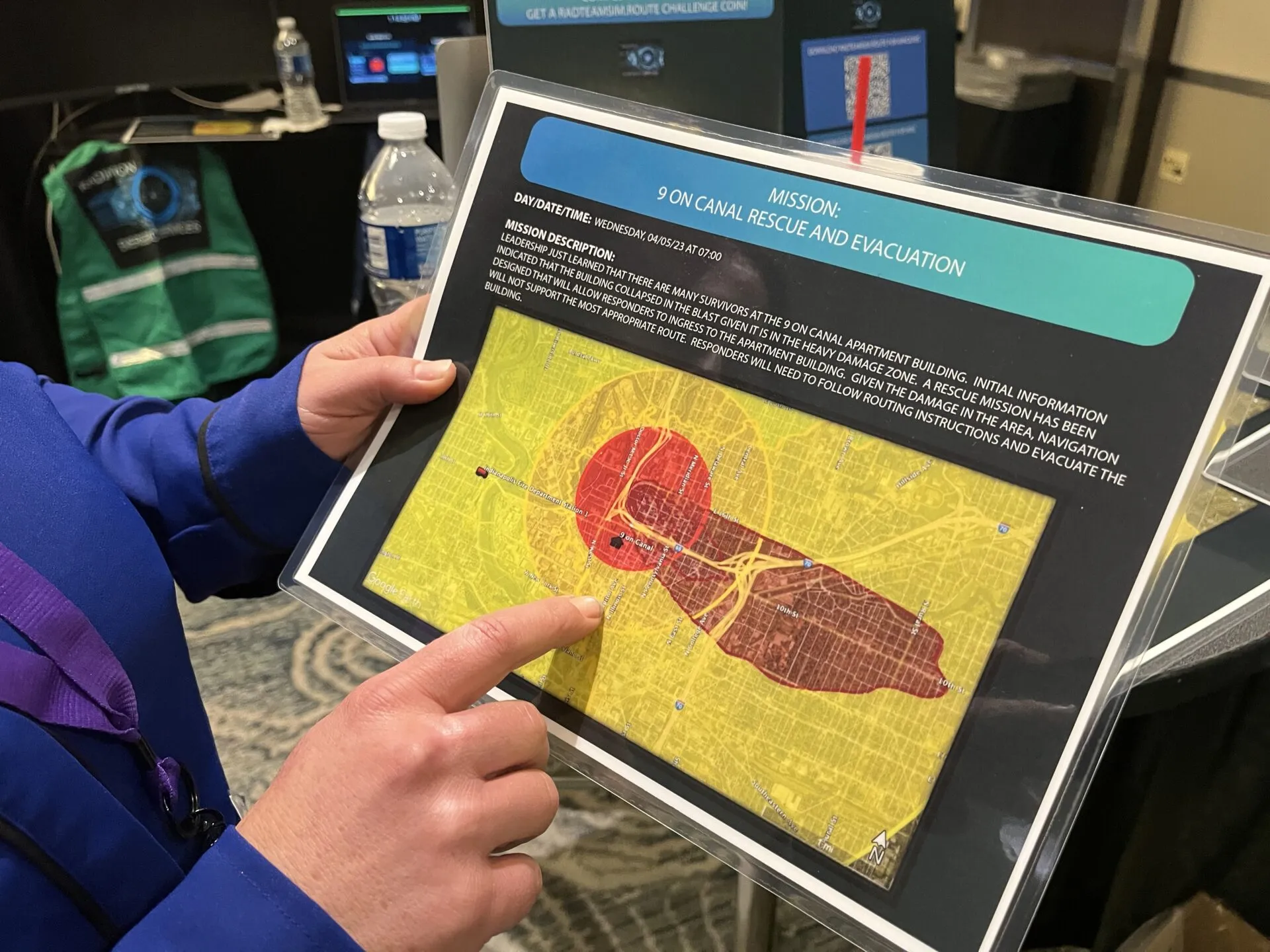

It’s a warm spring day in downtown Indianapolis. An emergency operations team is delivering its situation report, one of several coming in from county governments and field teams responding to the chaos after a 10-kiloton nuclear device exploded in the city, just an hour earlier. Radiation, fires, and limited capacity at area hospitals and shelters complicate treatment of the wounded and communication with a panicked public.

One team leader relays a request from a heavily damaged adjacent county to help house survivors of the nuclear blast. Field teams report back on the radiation doses they’ve received while navigating a pickup truck through the city to respond to people who need assistance.

“We didn’t wreck anything,” one driver says.

“Show-offs!” yells another.

These reports are part of a three-hour drill I’m observing inside a large conference room at the Hyatt Regency hotel in Indianapolis. The jurisdictions used in the exercise are fictional, with sci-fi county names like Endor, Caprica, and Druidia. The truck missions are run on a video-game-like simulator, designed by a former Energy Department scientist who, among other things, assessed radiological impacts in Japan during the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster.

The team members and radiation experts guiding the proceedings are all gathered for the four-day National Radiological Emergency Preparedness (NREP) conference, an annual meeting of emergency management officials from local, state, and federal government agencies, along with representatives of utility companies, health organizations, and vendors with products ranging from expert guidance to Geiger counters.

These are the people who try to plan for the aftermath of some of the worst imaginable radiological emergencies. The goal is to make sure that they, and the public, have some idea how to respond when disaster strikes.

The mood around the conference tables is typical of most any professional conference, with a shared travel-weariness offset by occasional jokes amusing only to insiders. After a short break, Bill Irwin, who leads the nuclear detonation drill, tries to get participants’ attention to start its next part. “As is the case in real world emergencies,” he announces, “they roll on despite the fact that people are trying to get pretzels.”

Despite the jovial atmosphere in the room, the events being contemplated are deadly serious. They’re based on the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) “Planning Guidance for Response to a Nuclear Detonation,” one of several major scenarios—including the use of a dirty bomb or chemical weapon—that federal, state, and local agencies have developed plans for and trained on in the years since 9/11.

Irwin is a member of a volunteer group of subject matter experts known by the acronym ROSS (Radiological Operations Support Specialists); they attend conferences and trainings like this one to help local officials coordinate their emergency plans during a radiological disaster. The ROSS group was established in 2015 by FEMA’s Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear Office after a decade-long assessment identified gaps in the United States’ preparedness for use of an “improvised nuclear device.” Selected from locations across the country, ROSS experts can be called on in an actual emergency to support local authorities quickly.

Like other ROSS volunteers helping with the proceedings and many of the 300-odd conference attendees, Irwin has a background in health physics, a field focused on the biological effects of radiation, from dental X-rays to nuclear fallout. In his day job, he leads the Radiological and Toxicological Sciences Program at the Vermont Department of Health.

He keeps the drill moving. Standing at a podium in front of a Powerpoint slide with bullet points like “Initial public messaging” and “Initial instructions to first responders,” Irwin says, “So, this is one of the sad ones. It talks about how many people within certain areas have died.” He’s referring to a mock report generated for the drill that includes the immediate estimated casualties of a nuclear blast in the notional city—within the severe and moderate damage zones around ground zero, nearly 90 percent of the population, or about 49,000 people, are killed or injured. Irwin notes it’s important to prepare local authorities and first responders for catastrophes of that scale. “This is something that we have to come to grips with, that there were a lot of deaths. It happens in natural disasters too,” he says. After all, the 2004 tsunami in the Indian Ocean killed more than 200,000 people. “So don’t think just because this is a nuclear detonation, we have to be afraid to talk about what we’re doing the [first] day.”

The storyline of the 10-kiloton drill dates to FEMA’s 2010 guidance documents. The latest version of the nuclear detonation scenario, published in 2022, outlines proposed response to nuclear explosions as large as 100 kilotons—the yield of most individual warheads currently deployed by Russia. Drilling on the consequences of a nuclear detonation means some of the emergency protocols appropriate during a less explosive accident—say, a reactor meltdown—get tossed out the window. For instance, Irwin notes, emergency workers responding to a nuclear detonation may not be able to avoid radiation exposures that are above—and perhaps significantly above—those allowed in less dire situations.

Most of the work that goes into radiological emergency planning is more mundane than reacting to extreme events like nuclear terrorism or war. The main context of emergency preparedness discussions at the conference involves accidents at nuclear power plants. The conference features three days of presentations on everything from from flying drones that detect radiation at accident sites to former journalists who help officials practice interacting with the media during an emergency.

The conference was first held in 1990 to help state authorities sort out how to implement federal regulations that emerged after the United States' worst nuclear power emergency, the Three Mile Island accident in 1979. Ken Evans began attending three decades ago; most of the people I meet at the conference make sure to mention his name. Evans started as a health physicist in Arkansas in the 1970s, worked for both utility companies and state agencies, and recently retired from his role as a radiological emergencies specialist with the Illinois Emergency Management Agency. When I catch up with him, he’s only got a few minutes to talk before he has to leave for a side-meeting with FEMA officials about some updated regulations. A lilting Arkansas accent makes his precise recitation of arcane Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) codes almost pleasant. (“NUREG-0654, you may have heard of that?” he says with a chuckle. “That’s the Bible of emergency preparedness.”)

Before the Three Mile Island accident, nuclear utilities (known formally as licensees) only had to demonstrate “reasonable assurance” of emergency preparedness onsite—that is, at the nuclear power plant facilities themselves—to be licensed to operate. “Emergency preparedness for offsite was purely voluntary,” Evans says. After the accident, the NRC made nuclear plant licensing contingent on preparedness for offsite emergencies as well (based on a 10-mile zone for atmospheric radiation and a 50-mile zone for “ingestion pathways,” like contamination of water and agricultural systems).

Evans tells me how emergency planning for nuclear plant emergencies developed since the 1980s in phases: the creation of the new off-site emergency regulations after Three Mile Island; increasing formalization of FEMA’s planning guidance in the 1990s (alongside the NREP conference); the emergence of the “all hazards” approach to emergencies in the aftermath of 9/11 and hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005; and the evolution of new standards since the tsunami and reactor meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in 2011.

In the beginning, Evans says, offsite emergency planners weren’t exactly sure how to apply the new regulations, let alone coordinate and standardize preparedness across states and the country. “Here we are, all stumbling around, including the regulators themselves,” Evan says, referring to FEMA and the NRC. “I mean, it’s one thing to write things out, it’s another thing to implement things.” So after a decade or so of uncertainty about how exactly to follow the rules, a group of frustrated state officials convened the first radiological emergency preparedness conference in 1990. “It was a chance for everyone to get together, share experiences, try to figure out what I would call basic information. But now we've kind of evolved on that,” Evans says. In the years since, the NREP conference has become known as the most important opportunity for radiological emergency preparedness organizers and trainers to discuss changes to federal regulations, share state of the art tools and techniques that can be passed on to local emergency workers, and workshop ideas with counterparts from across the country.

As Evans describes the evolution of the conference, we’re distracted by a robot dog walking behind him. One of the vendors is demonstrating its customized Boston Dynamics model, Cerberus QUGV, which has been outfitted with a bank of wireless radiation sensors and dosimeters to assist with risky exploration of irradiated spaces. Turning back to me, Evans says, “We didn’t have any robots at the early conferences … but the conference has grown in attendees and scope!”

Cerberus QUGV is a Boston Dynamics robot customized by RADeCO, a Connecticut-based company that specializes in air sampling and detection systems for the energy and defense industries. The robot dog is equipped with radiation detectors and a wireless system to transmit data from risky locations to remote operators.

At an afternoon session providing an overview of emergency management, Todd Smith of the NRC’s Office of Nuclear Security and Incident Response explains that planners should focus on the most likely incidents, but can extend preparedness to less likely accidents. “You’re an emergency manager—you have to balance the resources of your community, right?” Smith contrasts the likelihood of radiological emergencies with wildfire, flood, and hurricane probabilities, and turns to a slide that puts the probability of certain kinds of nuclear reactor failure at 1 in 10 million years, or in some cases, he says, “beyond the lifetime of the universe.”

“All the uncertainty, all the unknowns. That’s why we’re doing what we’re doing,” Smith says.

Because most of the protocols (and funding) around radiological emergencies emerge from a regulation framework that governs nuclear power plants, accidents involving commercial power are the main focus of radiological preparedness in the United States. But the people attending the conference also prepare for a variety of other radiological situations, like lost radioactive sources, or rocket launches with radioactive payloads (like the plutonium-heated Perseverance Mars rover), and, occasionally, nuclear detonations. Although those incidents are rare compared to natural disasters and other industrial accidents, the conference is taking place just weeks after several reports of radioactive items being lost and recovered and during an ongoing leak of tritium at the Monticello nuclear plant in Minnesota.

On an elevator during a lunch break, an attendee from Minnesota tells another how she noticed her own farm pictured in a slide at one of the sessions. “I said, ‘That’s my chicken coop!’” Her farm had been used as the site for an exercise on ingestion pathways, which helped emergency planners practice taking samples, but also gave them some unexpected insight that could be important in a radiological emergency: Cows, like cats, use their tongues to groom each other, which means if contaminated material lands on their hair, it can end up inside their bodies too.

Tornadoes roll across the Midwest while I’m standing at a booth with representatives of IPAWS, the FEMA system that pushes cell phone notifications about weather alerts, child abductions, or even incoming missiles. As I head down to the next session I run into Kelly Van Buren, Emergency Services Coordinator at the San Luis Obispo County Office of Emergency Services (which handles offsite emergency planning for California’s only remaining nuclear plant, Diablo Canyon), who will lead management of the NREP conference next year. She pauses to show me a photo of a semi-truck that has flipped over in the storm and is blocking the I-65 highway north of Indianapolis. Then she races off.

Moments later I’m not surprised to see an alert on the conference’s smartphone app, warning anyone traveling northbound about the tornadoes and the accident. This is a conference of emergency preparedness experts, after all.

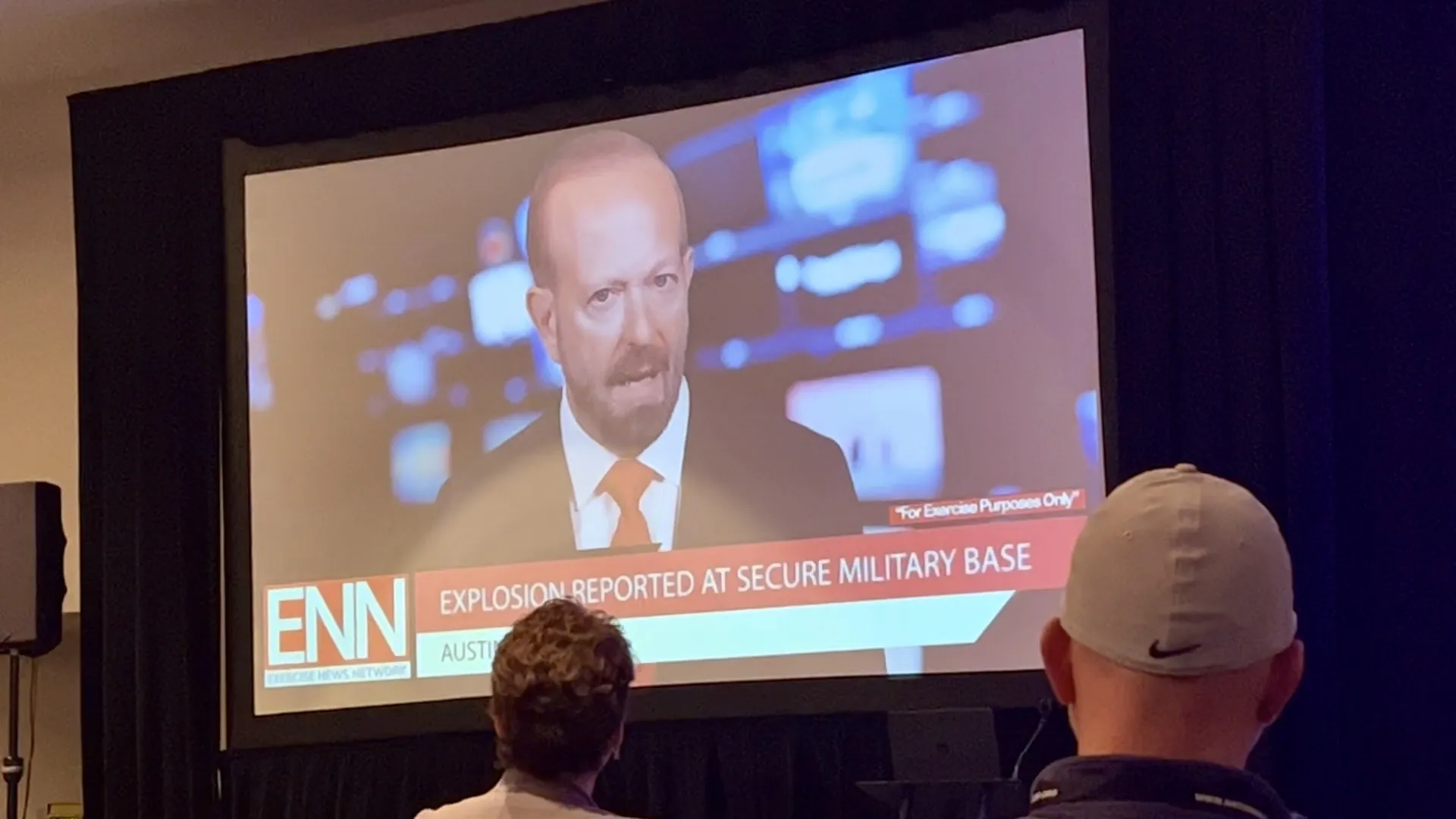

Communication is a primary theme of the conference; about one in five sessions are explicitly devoted to improving public messaging around emergencies. At an interactive spokesperson training, Eric Singer warms up the couple of dozen people gathered for his session while his colleague sets up a tripod with a camera (or as Singer calls it, an ENG—“electronic news gathering device”).

Singer is a former broadcast news anchor who now works as an emergency management communication specialist with the Risk and Crisis Communication Program team from Argonne National Laboratory. The team provides hands-on media training for emergency responders across the country. Singer’s presentation provides tips on best practices for appearing on camera, ranging from how to keep one’s eyes on a camera lens to avoiding jargon and acronyms and staying on message. One slide is titled “What to say when you can’t say anything.” The idea is to learn “how to say ‘no comment’ in a different way,” Singer explains, but without missing the opportunity to educate and inform the public.

Focus instead on “how the stew is made,” Singer says, like outlining the steps authorities and scientists are taking to gather more information and respond. Some of this advice might seem to enter spin doctor territory, but the point isn’t to obfuscate. Uncertainty and confusion can exacerbate dangerous situations, or make a minor problem worse by exaggerating hazards and causing panic during an emergency. So the goal of the exercise is connecting with the public to get clear information across. Singer’s next session is in the same room and goes even deeper. It’s called “Empathy isn’t for Weaklings.”

Communicating clearly is a thread that runs through nearly all the workshops I attend at the conference, even the more technical ones. At a day-long introduction to the Federal Radiological Monitoring and Assessment Center (FRMAC), Brian Hunt details the various software systems the center’s teams use for collecting and analyzing radiation data. A tool built by Sandia National Laboratories to track data requests from other agencies looks a bit like the popular project management app Trello, but it’s currently being used to support FRMAC’s tracking of atmospheric conditions during the war in Ukraine.

Making sure new information is vetted and accessible before it’s used to communicate updates to the public is an important part of FRMAC’s work in emergencies. “Most of what we do is not intended for the public, because it’s not couched in terms that people will understand,” Hunt says. “The general public doesn’t know anything about radiation, and you’re going to have to couch it properly, so that the proper messages get through.”

The phrase “right of boom” is used repeatedly during the four days of the conference, referring to what is done to respond after some event (the boom) creates a radiological emergency. Everything done to prevent those events from happening is “left of boom”—that might include reactor and power plant safety, but also nonproliferation, arms control, and even nuclear deterrence. The emphasis at NREP is almost entirely on what’s right of boom—for the most part, this is a conference of health physicists and emergency managers, not nuclear reactor designers or defense experts.

But some of the conference-goers find it problematic that these areas remain so separated. Arnold Bogis spent his early career working on issues like nuclear non-proliferation (left of boom) at think tanks like Harvard University’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Today he works for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, where he aided a CDC-funded project developing guidance for use of cytokines to treat severe radiation exposure after a nuclear explosion (right of boom). This is his second year at the NREP conference, but he’s been involved with the radiological emergency crowd for a while, traveling as far as Guam to help teach local emergency workers how to deal with radiation.

Based on his experience with both left and right of boom experts, Bogis feels a lack of communication between them has real implications. He cites the crisis at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant in Ukraine as one example of something both communities should be interested in. “I haven’t heard anything about that plant here at all, not one mention. … No one is talking about this ongoing experiment in nuclear safety,” he says, and he’s largely right—the most I hear about it is a comment during a slideshow of a tour to Chernobyl on the last morning of the conference.

“You rarely see the FEMA people over at nonproliferation conferences,” he says. “I find it pretty unlikely … that anybody at this conference, even probably the federal folks, has ever read anything out of Arms Control Today.”

With more interaction between the fields, those working to prevent use of nuclear weapons could incorporate the realities of emergency planning into their research and their advocacy. Likewise, emergency planners would benefit from deeper understanding of nuclear defense and nuclear energy debates, especially when it comes to public communication. So Bogis would like to see experts from think tanks like the Nuclear Threat Initiative and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace attending, and even presenting, at future NREP conferences. “Come and give a talk here,” he says, “I bet people will be fascinated.”

The felicitously named Martin Vigil participated in the 10-kiloton nuclear detonation drill with Bogis and is also concerned that not enough is being done to prevent the nuclear disasters. When I introduce myself after the drill, he tells me has his own homemade Doomsday Clock on his mantle at home, and he points out that he’s wearing a shirt embroidered with his own version of the old Civil Defense logo.

Today Vigil is the director of the Santa Fe County Office of Emergency Management, which among other things helps secure transports out of Los Alamos. (“We don’t know what’s in there,” he says.) Vigil is concerned about global nuclear tensions and broken arrows (close calls with nuclear warheads). He’s also very worried that the country isn’t prepared for a nuclear detonation. “Nationwide, there’s, I think, 1,800 burn beds and less for pediatric specialties,” he says. "Some of the modeling for just a 10-kiloton detonation, you know, you’re up in the 80,000-to-100,000 range [of burn victims]. How do we even begin to manage that?”

Most people I speak with at the conference are concerned about rising nuclear tensions worldwide, in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the dangers surrounding the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant. But few tell me they see a heightened threat of nuclear war changing much about how they prepare for emergencies. Rae Walker, an emergency preparedness coordinator in the Radiation Control Program at the Texas Department of State Health Services and the outgoing chair of the NREP conference steering committee, says her own impression is that “the tempo is different” between the concerns of those who focus on weapons of mass destruction and those who focus on emergency preparedness with nuclear plants. One of the ROSS volunteers puts it another way: If they’re able to respond to a major nuclear catastrophe, they’ll follow their plans and training; if not, well, it’s probably better to be closer to ground zero.

As support for nuclear power has waned since the 1980s and plant development in the United States has stalled, the nuclear industry has suffered significant declines in the size of its workforce. It’s a problem not just for the nuclear plants, but also for emergency preparedness; fewer people with decades of knowledge and experience—the Ken Evanses of the world—are available to mentor younger planners. Walker notes that retirement of older professionals (including “Navy nukes,” as Van Buren calls those who got into the nuclear field through their work on nuclear submarines) has been an increasing concern, and that the pandemic appears to have accelerated the process.

But the conference may be able to help with the aging-out problem. Walker says that her committee has only recently started gathering more detailed demographic data about conference registrants, but that this year’s conference does skew younger than it has before. (The youngest person attending appears to be a 19-year-old emergency responder from St. Lucie, Florida.) Perhaps more important, many of this year’s attendees are new to the conference itself. During the opening plenary session, Walker asks any newcomers to stand, and a good third of the crowd gets out of their seats.

One of the youngest members of the conference steering committee is Jack Wiley. He’s in his 20s and studied nuclear engineering as a way to work on green energy, a common motivation for others his age who are concerned about climate change. He switched his attention to health physics and now works in the Radiological Emergency Preparedness section of the Washington State Department of Health. He’s been working there four years and has already seen a dozen retirements in that time. He tells me there’s an especially big gap between those in their late 40s or older, and people his age who are early in their careers. “They don’t know the stories behind what happened. They might read it in a textbook, but have no context for it,” Wiley says. “I'm trying to bridge that gap by, you know, being present and asking those things and hearing those stories firsthand. … Really trying to extract out as much of that information before people retire.” I ask whether he’s noticed any concern or changes in preparedness given the situation with the Zaporizhzhia plant in Ukraine. Besides getting new background radiation readings in case something disastrous does happen, he hasn’t noticed his colleagues taking extended precautions. But paying attention is important. “I like historical things happening,” he says. “Not things like this. But it’s interesting to me to see the reaction of the [radiological emergency preparedness] community based on historical events of this scale.”

A much less dramatic historical event is part of NRC Commissioner David Wright’s keynote address at the conference. He notes that the new Vogtle 3 reactor in Georgia was hooked up to the grid just that weekend, 14 years after construction began, and the first time a new reactor has generated commercial power in the US since 2016. There’s no cheering among those assembled, but no heckling either. Few of the people I speak with express strong opinions about nuclear energy one way or another, so I don’t get a good sense of how many think this emergency preparedness work is worth the effort, to keep aging nuclear plants in business. Do the energy benefits of nuclear power justify living with the uncertainty and risks that these emergency experts must constantly prepare for year after year?

New developments may change the calculus. In January, the NRC certified a small modular nuclear reactor design for the first time. The potential impact of an industry-wide shift to small modular reactors comes up now and then in a few sessions of the conference, but most still see that as a long way off. One thing that no one doubts though, is that the new regulations that accompany the new reactors will probably change how offsite emergency planning is done. According to Evans, it’s possible that with the new reactors, the NRC’s required emergency planning zones will be reduced—potentially eliminating the need for the offsite planning that’s been in place since the Three Mile Island accident over four decades ago. But the broader need for radiological emergency preparedness won’t go away anytime soon. It will take many years to get new reactors online; it also takes years to decommission them.

And as the participants in the first day’s drill established, there are other dire possibilities to be prepared for.

Thomas Gaulkin is the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientist’s multimedia editor.

Keywords: FEMA, NRC, Nuclear Regulatory Commission, emergency planning, emergency preparedness, radiological emergencies

Topics: Nuclear Risk

[addthis tool="addthis_inline_share_toolbox"]

Whare is ham radio in all this?

It would be nice to have this article and many others in Spanish

If any American city were to be attacked by a Russian nuclear missile, the warhead would probably be at least 500 kilotons or maybe 800 kilotons now they have the Sarmat missiles. Considering expenses and logistics, it hardly pays to send a dinky 10 kiloton weapon when a 500 kiloton warhead is only about twice the size and weight, and does a lot more damage per unit of effort and risk and expense invested. Current Russian submarine missiles are generally in the 200-300 kiloton range, but with the newer larger subs those warheads will become correspondingly larger. There is an… Read more »

I think the primary focus for such events is nuclear terrorism – a homemade fission device of low to moderate yield or a “dirty” bomb (radiological hazard spreading device using conventional explosives). An all out nuclear war involving strikes on cities – the volume of destruction and the size of the rad hazard involved would instantly outstrip whatever resources these various organizations might other-wise bring to bear. Indeed, many of the personnel involved might be victims in the rubble themselves. As poorly prepared as we are for nuclear terrorism – we are even more woefully unprepared for a nuclear war.

The beginning of this article reminds me of the radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds. The beginning is unnecessarily sensational in that it portrays a simulation as fact.

The tone of these meetings, set by the choice of fictitious county names, reflects the emphasis on battles and winning that permeates many of the U.S. publics’ choices for TV series, movies and especially games. I looked these up. “Vega” is a brawny street fighter who, after inflicting a full measure of mayhem on his opponent, always wins. “Endor” is the scene of a Star Wars battle where, after inflicting and receiving a full measure of mayhem, the Ewoks defeat the “Empire” and bury Darth Vader. “Caprica” is a TV series about inventors of an android that attempts to inflict a full measure of… Read more »

I also find that there are no “practical” nuggets for the rest of us. Which measures are discussed? What do they propose to do? How do they envisage to organize things? Will the army/police/ intervene? How shall they act to protect the population?

Will a mechanic dog come to the rescue? A very disappointing albeit folkloric read