The COVID public health emergency ends today. Is the country prepared for another pandemic?

By Matt Field | May 11, 2023

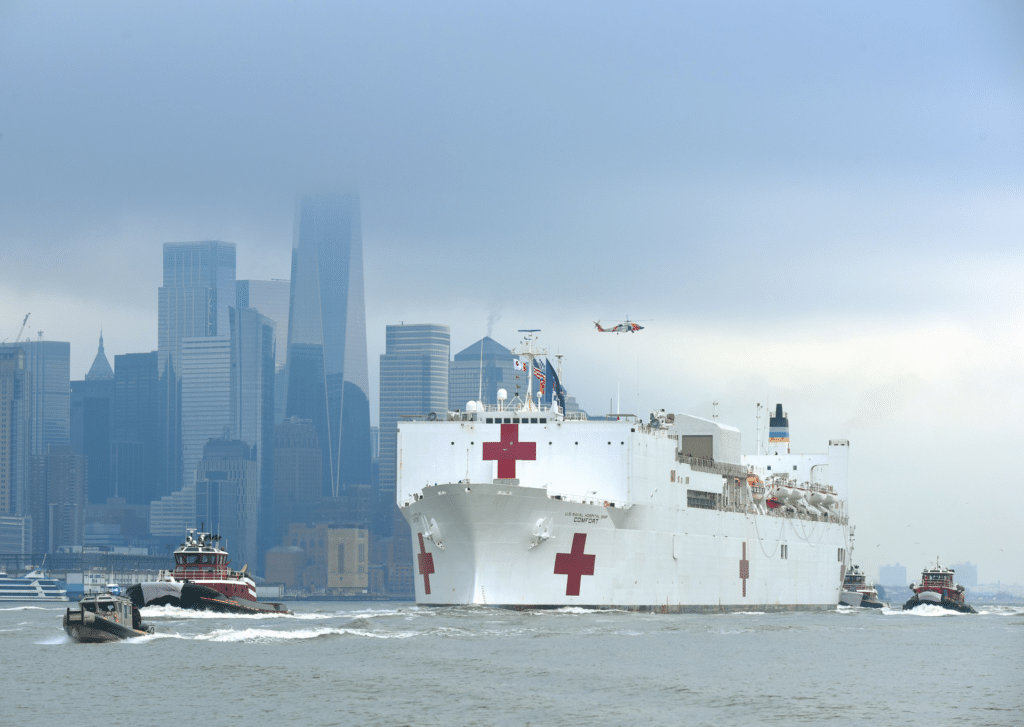

Boats guide a hospital ship off of New York City in 2020. Credit: John Q. Hightower/US Coast Guard.

Boats guide a hospital ship off of New York City in 2020. Credit: John Q. Hightower/US Coast Guard.

It’s a wrap. After more than three long years, the public health emergency for COVID-19 in the United States is ending. The Biden administration in February announced that the measure, first invoked in March 2020, would expire today. Alongside the US decision, the World Health Organization (WHO), similarly ended its public health emergency of international concern designation for COVID. By many measures, the impact of the virus—both in the United States and around the world—is receding, but experts warn that could change if and when a new immune-evasive variant crops up.

COVID deaths have been dropping steadily this year. Between April 27 and May 3, a little over 1,100 people in the United States died. Some 70 percent of the country has received primary vaccinations and, as of late last year, half the country said they had been infected by the COVID virus. Consequently, the United States now has a considerable amount of immunity against the disease. The current weekly death rate, if it holds, would mean that COVID will continue to exact a high yearly toll, similar to that of a bad flu season. Of course, a new viral variant could emerge, experts say, or, as other threats like H5N1 avian influenza lurk in the shadows, an entirely new pandemic could strike.

How serious is a COVID infection now? Already by last fall, support for masking and vaccine requirements had plummeted, with just a quarter of survey respondents in the United States supporting masking and one-third supporting vaccine mandates, according to CBS News. Abandoning these measures puts people at greater risk of COVID infection—but by the same token, the consequences appear to be less dire than at earlier points in the pandemic, when weekly deaths in the United States were many times higher than they are now. Experts disagree on the true risk of COVID, however, with some saying it’s akin to the flu and others disagreeing.

The Biden administration said Tuesday that due to vaccines, tests, and therapeutics, “COVID-19 is no longer the disruptive force it once was. Since January 2021, COVID-19 deaths have declined by 95% and hospitalizations are down nearly 91%.”

And, of course, death and hospitalization are not the only adverse consequences of COVID-19. Long COVID continues to be a risk even as the more easily measurable pandemic trends decline. As of January, 28 percent of people who had ever had COVID in the United States reported having had or still having long COVID, which can include symptoms such as fatigue or heart palpitations. That figure, though, is down from 35 percent in June 2022.

What will lifting the pandemic emergency mean? The Biden administration said that access to free vaccines will continue, even as the “traditional healthcare market” takes over. While most people will receive free vaccinations, according to Reuters, they may have to pay for at least a portion of the cost for tests and treatments going forward.

A big concern will be the comprehensiveness of public health data. Data on cases and vaccinations is critical to controlling the spread of infectious diseases, but the ability of the US government to collect this information will diminish after the COVID emergency ends.

South Carolina, for instance, doesn’t allow the sharing of vaccination data except in certain cases, like a public health emergency, according to The Washington Post. Health care facilities nationwide will no longer be required to report test results. And, more broadly, the way data is reported from clinics, to local health departments, to state health agencies, and then to the federal government is “inconsistent and fragmented,” according to the Post’s Lena H. Sun. With the end of the emergency declaration, and as public attention to COVID dwindles, efforts to improve public health data collection could also lose steam.

The CDC will have less ability to collect COVID data, the agency said. That means, according to Reuters, that the color-coded COVID-19 Community Levels system that the agency has been updating will cease, although another measure based on hospital admissions will continue. “We will still be able to tell that it’s snowing, even though we’re no longer counting every snowflake,” CDC Principal Deputy Director Dr. Nirav Shah said in a press call.

What does the future hold? As has happened repeatedly during the pandemic, a new variant could spell another surge in cases. Experts told the White House recently that there’s about a 20 percent chance in the next two years that a variant causes an omicron-like surge in cases. After the omicron variant was first detected in South Africa in late 2021, cases sky rocketed around the world. In the United States some 700,000 cases a day were being reported in January before the numbers began to declining sharply. Since then, omicron has spawned new so-called “subvariants,” although none has caused the disruption of the original strain.

“We have continued detection of ‘cryptic lineages’ in wastewater surveillance, suggesting that it’s not uncommon to have run-away evolution of a persistent infection within a single individual,” Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center computational biologist Trevor Bedford, one of the experts who shared his projections with the White House, told The Washington Post.

The Biden administration wants to keep a lid on COVID by continuing to develop countermeasures. It’s set aside $5 billion in funding for new vaccine development, including nasal vaccines that could help block infection better than the current shots or vaccines that target an array of coronaviruses instead of just a couple of strains of SARS-CoV-2—the virus that causes COVID. But that funding, which will come from unspent COVID funds, could be at risk due to the ongoing budget dispute in Congress, which wouldn’t provide new money for the program. Republicans want to reclaim the unspent federal pandemic aid.

Experts worry about leaving the fight against COVID in the review mirror. “Even if the pandemic is over, endemic covid is still going to be a major public health concern,” Bedford told the Post.

Are we ready for another pandemic? The country and the world remain vulnerable. H5N1, for instance—a bird flu strain which has been causing outbreaks in wild and domesticated poultry—has affected numerous mammals by this point, including farmed ferrets. Experts worry it could evolve to become easily transmissible among humans. Climate change, farming practices, human encroachment into wildlife areas, and laboratory safety practices, likewise could present a risk of another disastrous disease outbreak.

Perhaps most worrisome, the public health sector that would respond to to a future pandemic has been gutted. Older employees are retiring and younger ones are leaving, with some 70,000 workers are at risk of leaving public health jobs in the next year. That number will come from a workforce that comprised 200,000 workers at the start of the pandemic, Kimberly Ma, a fellow for the Bulletin calculated in a recent column. Future vaccination campaigns, data analysis efforts, and other essential tasks will rely on this workforce—which, Ma said, may be “less prepared for a pandemic than it was in late 2019.”

Francis Collins, the former director of the National Institutes of Health, told The New York Times, “No,” when asked whether the country was ready for another pandemic. Other officials also sound less than reassuring.

“We’ve learned a lot from Covid,” US Health Secretary Xavier Becerra told the Times. “We’re prepared to deal with Covid—even some of the variants as they come. If it’s something totally different, avian flu, I become a little bit more concerned. If it becomes some kind of biological weapon, you know, that’s another issue altogether.”

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: COVID-19

Topics: Biosecurity