My grandfather helped build the bomb. ‘Oppenheimer’ sanitized its impacts

By Emily Strasser | August 9, 2023

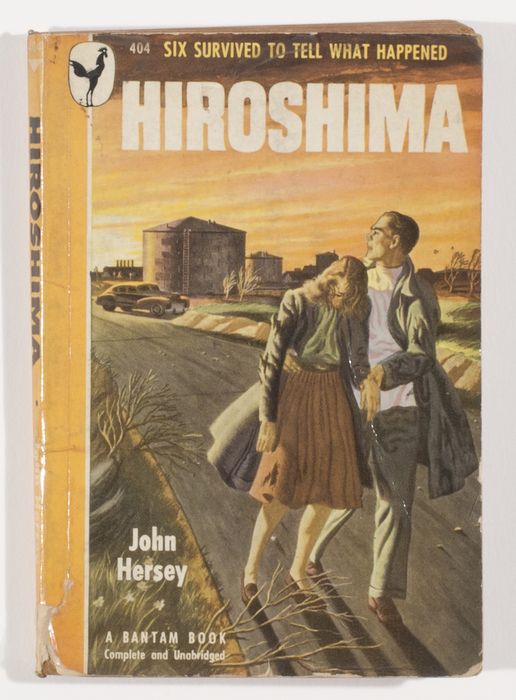

Bantam Books 1948 edition of John Hersey's book Hiroshima, originally published in 1946. Museum purchase, 2008, International Center of Photography

Bantam Books 1948 edition of John Hersey's book Hiroshima, originally published in 1946. Museum purchase, 2008, International Center of Photography

At the theater where I saw Oppenheimer on opening night, there was a handmade photo booth featuring a pink backdrop, “Barbenheimer” in black letters, and a “bomb” made of an exercise ball wrapped in hoses. I want to tell you that I flinched, but I laughed and snapped a photo. It took a beat before I became horrified—by myself and the prop. Today is the 78th anniversary of the bombing of Nagasaki, which killed up to 70,000 people and came only three days after the bombing of Hiroshima that killed as many as 140,000 people. Yet still we make jokes of these weapons of genocide.

Oppenheimer does not make a joke of nuclear weapons, but by erasing the specific victims of the bombings, it repeats a sanitized treatment of the bomb that enables a lighthearted attitude and limits the power of the film’s message. I know this sanitized version intimately, because my grandfather spent his career building nuclear weapons in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, the site of uranium enrichment for the Hiroshima bomb. My grandfather died before I was born, and though there were photographs of mushroom clouds from nuclear tests hanging on my grandmother’s walls, we never discussed Hiroshima, Nagasaki, or the fact that Oak Ridge, still an active nuclear weapons production site, is also a 35,000-acre Superfund site. At the Catholic church in town, a pious Mary stands atop an orb bearing the overlapping ovals symbolizing the atom, and until it closed a few years ago, a local restaurant displayed a sign with a mushroom cloud bursting out of a mug of beer.

Oppenheimer does not show a single image of Hiroshima or Nagasaki. Instead, it recreates the horror through Oppenheimer’s imagination, when, during a congratulatory speech to the scientists of Los Alamos after the bombing of Hiroshima, the sound of the hysterically cheering crowd goes silent, the room flashes bright, and tatters of skin peel from the face of a white woman in the audience. The scene is powerful and unsettling, and, arguably, avoids sensationalizing the atrocity by not depicting the victims outright. But it also plays into a problematic pattern of whitewashing both the history and threat of nuclear war by appropriating the trauma of the Japanese victims to incite fear about possible future violence upon white bodies. An example of this pattern is a 1948 cover of John Hersey’s Hiroshima, which featured a white couple fleeing a city beneath a glowing orange sky, even though the book itself brought the visceral human suffering to American readers through the eyes of six actual survivors of the bombing.

The Oppenheimer film also neglects the impacts of fallout from nuclear testing, including from the Trinity test depicted in the film; the harm to the health of blue-collar production workers exposed to toxic and radiological materials; and the contamination of Oak Ridge and other production sites. Instead, the impressive pyrotechnics of the Trinity test, images of missile trails descending through clouds toward a doomed planet, and Earth-consuming fireballs interspersed with digital renderings of a quantum universe of swirling stars and atoms, elevate the bomb to the realm of the sublime—terrible, yes, but also awesome.

A compartmentalized project. The origins of this treatment can be traced to the Manhattan Project, when scientists called the bomb by the euphemistic code word “gadget” and the security policy known as compartmentalization limited workers’ knowledge of the project to the minimum necessary to complete their tasks. This policy helped to dilute responsibility and quash moral debates and dissent. Throughout the film, we see Oppenheimer move from resisting compartmentalization to accepting it. When asked by another scientist about his stance on a petition against dropping the bomb on Japan, he responds that the builders of the bomb do not have “any more right or responsibility” than anyone else to determine how it will be used, despite the fact that the scientists were among the few who even knew of its existence.

Due to compartmentalization, the vast majority of the approximately half-million Manhattan Project workers, like my grandfather, could not have signed the petition because they did not know what they were building until Truman announced the bombing of Hiroshima. Afterward, press restrictions limited coverage of the humanitarian impacts, giving the false impression that the bombings had targeted major military and industrial sites—and eliding the vast civilian toll and the novel horrors of radiation. Photographs and films of the aftermath, shot by Japanese journalists and American military, were classified and suppressed in the United States and occupied Japan.

The limit of theory. Not only is it dishonest and harmful to erase the suffering of the real victims of the bomb, but doing so moves the bomb into the realm of the theoretical and abstract. One recurring theme of the film is the limit of theory. Oppenheimer was a brilliant theorist but a haphazard experimentalist. A close friend and fellow scientist questions whether he’ll be able to pull off this massive, high-stakes project of applied theory. Just before the detonation of the Trinity test bomb, General Leslie Groves, the military head of the project, asks Oppenheimer about a joking bet overheard among the scientists regarding the possibility that the explosion would ignite the atmosphere and destroy the world. Oppenheimer assures Groves that they have done the math and the possibility is “near zero.” “Near zero?” Groves asks, alarmed. “What do you want from theory alone?” responds Oppenheimer.

Can the theoretical motivate humanity to action?

One telling scene shows Oppenheimer at a lecture on the impacts of the bomb. We hear the speaker describe how dark stripes on victims’ clothing were burned onto their skin, but the camera remains on Oppenheimer’s face. He looks at the screen, gaunt and glassy-eyed, for a few moments, before turning away. Americans are still looking away. As a country, we’ve succumbed to “psychic numbing,” as Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell call it in their book Hiroshima in America, which leads to general apathy about nuclear weapons—and pink mushroom clouds and bomb props for selfies.

On this anniversary of Nagasaki, the world stands on a precipice, closer than ever to nuclear midnight. The nine nuclear-armed states collectively possess more than 12,500 warheads; the more than 9,500 nuclear weapons available for use in military stockpiles have the combined power of more than 135,000 Hiroshima-sized bombs.

If Oppenheimer motivates conversation, activism, and policy shifts in support of nuclear abolition, that’s a good thing. But by relegating the bomb to abstracted images removed from actual humanitarian consequences, the film leaves the weapon in the realm of the theoretical. And as Oppenheimer says in the film, “theory will only take you so far.” Today, it’s vital that we understand the devastating impacts that nuclear weapons have had and continue to have on real victims of their production, testing, and wartime use. Our survival may depend on it.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Barbenheimer, Hiroshima, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Nagasaki

Topics: Nuclear Weapons, Opinion, Voices of Tomorrow

The movie is a biopic of Oppenheimer, not a drama about the horrors of nuclear war. As such, just about every single scene in the movie features Oppie himself. There are very few exceptions, flash of Jean Tatlock’s suicide being one that comes to mind. Was Oppenheimer at the sites of those bombings? Was he there afterwards? Then it makes perfect sense to not include that. Basically your criticism comes down to “Nolan made a movie about Oppenheimer instead of a movie I wanted to make”. You are free to rectify this problem by making your own film about whatever… Read more »

The film is about consequences. The consequences of our choices.Looks like you are avoiding that.

The author doesn’t mention the bombing of Tokyo on 9 March 1945 which destroyed 25% of the city and killed 100,000 to 125,000 people that night. Where is the protest? Just one bomb makes it worse? The bombs saved a possible 1,000,000 allied casualties and maybe a couple million Japanese civilians. I guess that would have been better? Judge people’s decisions on what they knew at the time, not 80 years later.

That wasn’t the purpose of the film. There is only so much time. The use of the bombs saved hundreds of thousands of American lives. The Japanese were brutal to their enemies, and killed millions of civilians.

There were humanitarian consequences for Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, Okinawa and every other Pacific island where Americans died.

You make many good points. But before we make yesterdays decisions with todays tools, let us say what you are never going to read in a school book. We came very close to losing that war. Our intelligence was poor both in the European and Pacific, Thr B-29s worked sometimes. As Paul Tibbets, the Enola Gay pilot ssid to me and many others, You would take off with four engines and come back with one.And the Japanese were better fighters than us. As Gen Kurabayashi, garrison commander for Iwo Jima said to his troops. When you die. Take 10 Americans… Read more »

Oh please stop. Stop. Stop being desperate to be offended and stop begging to be bludgeoned by depictions of the sins of the past. If the film had featured full, graphic scenes of the bombings – this author would have joined chorus decrying the insensitive nature of such images. Nolan would have been roasted for portraying Japanese suffering “from the point of view of a white man” or “exploiting pain”. This is a dead-end mindset where greviou offense is inescapable. Sanitized? Does the author not understand ART? Not every element needs to be explicitly shown to have dramatic weight. No… Read more »

Ms. Strasser-neither you nor I nor anyone who didn’t live through the horrors of the World Wars should sit in such smug judgment. The bomb ended the Second World War, at a terrible price to be sure. But estimates of the total deaths had we ended it with an invasion of Japan are even higher. The bomb also prevented the Third World War, which assuredly would have soon ensued but for the nuclear deterrent. By the end of WW2, homo sapiens had the knowledge and the bomb was going to be built. The US would either have its nuclear deterrent… Read more »

Oppenheimer Saved Millions of US Service Men and Women on top of millions of Japanese . Without Oppenheimer Who knows just how many would have perish under the Bushito Code, Hirahito , and Tojo .

The white woman with face peeling was Christopher Nolan’s daughter… It has a profound impact when the director puts his own child in that image. . you just have to know what you’re talking about before you write an article.

It’s supposed to make us haunted by the future and curiosity and discovery… It’s not about the past at all When I walked into the theater, I expected to see my favorite scientist with all backstory. Yet, his name wasn’t even mentioned. This is not about the Manhattan project. It’s not about Japan. It’s not about Germany. It’s not about the USA. It’s about Oppenheimer. It’s about the unique and isolating scientific mind. I work in science… I live science… Science offers a beauty that I find in no other discipline… I was wired this way, and it’s something I’ll… Read more »

I disagree. My wife and I are 70 ish. Our fathers fought in WW2. There was a lot more than a non Zero probability we would not exist without Hiroshima and Nagasaki. First, you neglect the images imagined by Oppenheimer of people radiated by the bomb. Those were pretty gruesome. Secondly, you ignore the brief, but most vital few seconds of the movie. It’s easy to miss as I did in my first viewing. Oppenheimer tells the scientists something similar to the following. We are theorists. We can imagine the real destruction. But the generals and politicians and people, they… Read more »

We were AT WAR with an enemy who believed in Death before surrender. . The Japanese had NO INTENTION of Surrendering , and were killing upwards of 30,000 innocent victims EVERY DAY in the conquered territories. Japan itself was getting ready for a mass killing of every POW in Japan (all 400,000 of them) then sacrificing EVERY Japanese in an attempt to cause mass casualties against the Allied Invasion . If Japan had got the Bomb first they would have used in in A NEW YORK MINUTE, and not said Boo about the victims. The only thing the Japanese resented… Read more »

Or if the Atom bombs weren’t used it was projected over 1 million Allied casualties and over 6 million Japanese casualties in a conventional invasion of Japan.

Quit tryin to make out the Japanese as victims then. They had engaged in total ruthless warfare in their subjugation of the Far East. Ever hear of the Rape of Nanking or the Bataan Death March?

The film Oppenheimer was about…. Guess what? Oppenheimer’s life. Let me repeat that. The film was about Oppenheimer’s life… It was actually NOT about either the first fission bombs, World War II, or the bombings in Japan. They are all elements of the story which Nolan handled well. Of course what happened in Japan was horrible and I am of the opinion totally unnecessary for reasons beyond the scope of this comment and the invention of the bomb changed the world forever but that doesn’t mean Nolan had to handle these elements any different than he did. Unfortunately, we are… Read more »

This evaluation of a single recent Hollywood produced film does not seriously alter the true history of what occurred and all of humanities experiences of what did occur. There is a very serious recent “re-writing” of history taking place in American culture, one that is quite appalling and extremely incorrect. Both of my grandfathers worked at Los Alamos during and after the Manhattan Project. one of them, before his death, was called and contacted by many media outlets every year on the anniversay of the Trinity Project, as well as both droppings on Japan. He flatly refused most of these… Read more »

All I know was that my mom was a nurse Captain on Okinawa and prepared for the main island invasion. She also knew all the body bags in inventory and fully aware of an outcome of a prolonged invasion against an enemy that started the conflict and would never surrender would entail. Those two devices saved her life and hundreds of thousands more.

That’s why the movie is called Oppenheimer, is because it’s a biopic of Oppenheimer. That’s why only 1/3 of the movie really focuses on the bomb, and the rest is hearings, personal life, etc. It’s not supposed to be about the bomb. So of course it will be sanitized. With all due respect, I think you may have gone in with an inaccurate preconception about the goal of the movie. I agree that a movie about the direct impacts of the bombings in Japan would be worthwhile, I’m just saying this movie was never intended to be that movie. In… Read more »

Exactly. I have had to explain to so many people, after they saw the movie, that the movie was called Oppenheimer not “The Bomb” or “Hiroshima “, when they complained that they still had questions regarding the bomb itself or the victims. There are so many resources, books, articles and movies on the bomb, it’s usage and it’s victims, that if you don’t know enough about it and it’s horrors it’s because you either don’t want to or haven’t yet taken the time to. Great reply Platypus.

Ok I’m sorry but to state that it was light hearted and made light of what was happening you must have miss understood the point of the movie. It clearly shows a man that is deeply affected by what he’s created. And to compare the atomic bombs use to genocide is quite a dull comparison. One is the systematic erasing of a group of people the other ended a world war and assured peace. Yes there was war after WWII but we went from two world wars In twenty years to smaller proxy wars. The dropping of the atomic bombs… Read more »

Wow. My father knew some project was scarfing up graduate physics students like him. He took a conscientious objector position and passed up his chance to work on the a-bomb project without knowing it at the time. Two scientists were doing an experiment with flasks of plutonium. The flasks got too close together and there was a burst of neutrons. The principle scientist was dead within the week from neutron poisoning. The man looking over his shoulder had a white streak in his hair. He was a friend and colleague of my father’s and we visited and had dinner with… Read more »

I havent seen Oppenheimer yet, but I would be very surprised if any movie addressed the points made here by Emily Strasser. I expect nuclear weapons will eventually be used not because they need to be but because they are weapons of hate and there is alot of that in America..

Aaawww Pearl Harbor, The Rape of Nanking, Battan Death March, Comfort Women, Beheading P.O.W.s, Medical experimentation on humans, using P.O.W.s for target practice, Kamikaze attacks, Imperial Japan practically got a free pass on atrocities.

I think this set of criticisms misses the forest with the trees. Nobody that I know who saw the movie did not experience an incredibly troubling set of concerns fears and sadness. Anyone who’s a student of human history can see how tribal and sectarian we are and how quickly we lose empathy for people different from ourselves. The real question is whether or not a species like humans has any business with this kind of weapon and almost everybody who saw the movie believes that the answer is no. Insofar as the movie gets us energized to debate the… Read more »

The focus of the movie is Oppenheimer, not the war, not Hiroshima nor Nagasaki. The film could have shown more of the aftermath of the bombings, but the film is not about that. The are multiple documentaries, photographs, interviews, and literature about the horrors the Japanese witnessed and endured because of the bombings. It’s available. People just have to look for it.