Henry Kissinger supported wars and coups. He also played a little-known role in eliminating bioweapons

By Matt Field | December 1, 2023

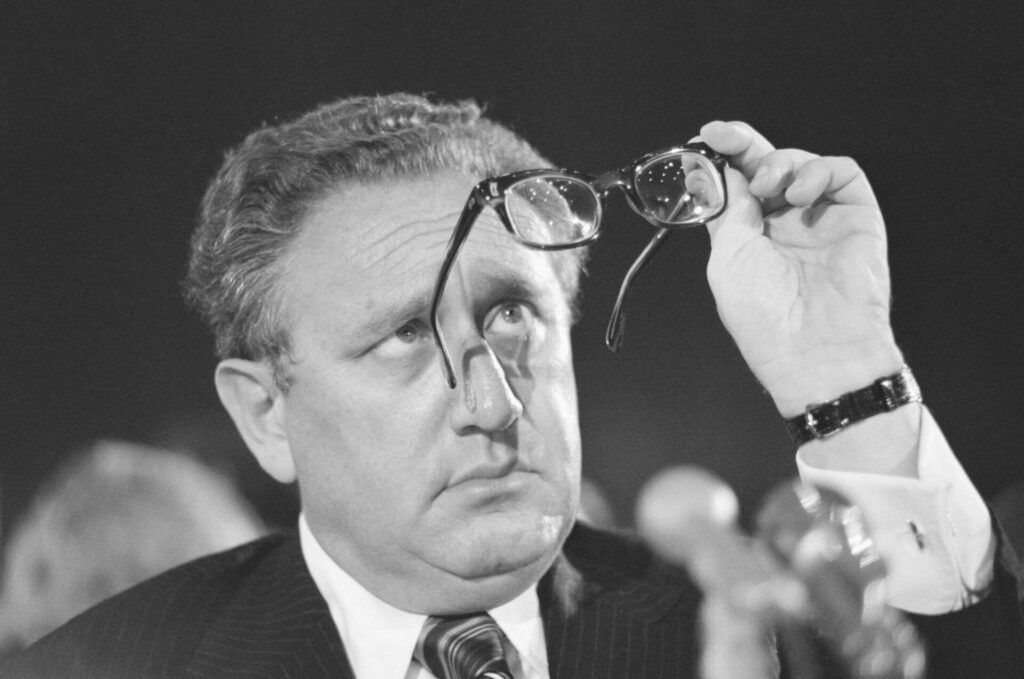

Former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger during a Senate hearing. Credit: Getty.

Former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger during a Senate hearing. Credit: Getty.

Observers of Henry Kissinger, the former national security advisor and secretary of state who died Wednesday at 100, seem to agree on at least one point: He was a towering figure in US foreign policy thinking during the Cold War and ensuing decades. Beyond that, assessments of his legacy vary widely. While in 1973 Kissinger won the Nobel Peace Prize, a later recipient of the same award summed up his life’s work as “tragic and ugly.” One obituary headline deemed Kissinger, who helped push the United States to engage with China in the 1970s and who worked to lower Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union, a “war criminal beloved by America’s ruling class.”

In Chile, many remember Kissinger for his support of a coup that saw the popularly elected socialist Salvador Allende deposed. As the military closed in on the presidential palace, Allende allegedly told his supporters to surrender before killing himself with an AK-47. Following, Allende’s death, Chileans lived under the brutal rule of General Augusto Pinochet, a coup leader infamous for the “disappearances” of thousands of Chileans that occured during his nearly two decades in power. In Cambodia, many recall Kissinger’s oversight of a relentless secret bombing campaign that killed up to 150,000 people. The presidential aide authorized nearly 4,000 air raids between 1969 and 1973, reportedly in pursuit of Vietnamese insurgent hideaways. The shock of these attacks, historians say, paved the way for Khmer Rouge insurgents to take over the country and impose their ruthless “Year Zero” policy of returning Cambodia to an agrarian state; some two million people died in the genocide.

Alongside Kissinger’s willingness to use US military power to achieve policy goals, he also worked toward ends that might soften his image, even if slightly, among his many critics. Echoing his earlier work pushing détente with US adversaries during the Cold War—efforts that would contribute to nuclear arms control—Kissinger became an advocate for nuclear disarmament in his later years. In a 2007 editorial in The Wall Street Journal, he and other prominent former US officials called for realizing the promise of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which requires that nuclear-armed countries eliminate their arsenals over time.

Decades before, when he was one of President Richard Nixon’s closest advisors, Kissinger also played a central if little publicized role in biological disarmament.

Through the late 1960s, the United States maintained a vast offensive biological weapons enterprise. Scientists at Fort Detrick in Maryland researched and produced pathogens for the military. At Pine Bluff Arsenal in Arkansas, employees filled weapons with germs. The latter facility had anthrax and tularemia bacteria, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, and other pathogens. In the Utah dessert, the military held open-air tests of viruses, bacteria, and chemical weapons. These efforts mirrored bioweapons development in the Soviet Union. But despite the large US program, many experts believed bioweapons to have little military utility, according to a comprehensive 2009 case study by Jonathan Tucker and Erin R. Mahan. The weapons had unpredictable effects. They sickened or killed people only after a delay. They might mutate or establish themselves in animal hosts, posing a public health threat. The US arsenal was intended to deter or retaliate against biological attacks, but presumably nuclear and other weapons could more efficiently fulfill that goal.

By the late 1960s, incidents with chemical weapons—including an accident with VX nerve agent in Utah that killed some 6,000 sheep—had focused Congress’s attention on the US chemical and biological warfare operation. Internationally, there were efforts to begin arms control negotiations around these weapons of mass destruction. And Kissinger led internal government deliberations over what to do with the US program. At one point, according to Tucker and Mahan, Kissinger, unhappy with a policy paper that contained both arguments in favor and against retaining biological weapons, produced his own paper that cut the points in favor of the offensive program. He included his personal recommendation to restrict the US program to biological defense, which involves the development of countermeasures such as vaccines.

Nixon ended up choosing to completely shutter the US offensive program. “Mankind,” he said at a press conference in November 1969, “already carries in its own hands too many of the seeds of its own destruction. By the example we set today, we hope to contribute to an atmosphere of peace and understanding between nations and among men.”

But later there turned out to be an issue with the new policy.

The administration had neglected to address an important component of the country’s bioweapons arsenal, toxins. Toxins are confusing because they’re produced by living organisms but are essentially chemicals. They can also be produced by chemical synthesis. For military officials at the time, toxins had some appeal. They can be more potent than even chemical weapons. The US arsenal included both incapacitating and lethal toxins, including 23,000 bullets loaded with deadly botulinum toxin.

After Nixon ended the US offensive bioweapons program, a reporter asked Kissinger about the toxin issue, prompting the presidential advisor to admit that the omission “was a slip up.”

It was a significant one. According to a 2002 paper by Tucker, back at Fort Detrick, scientists, “uncertain whether the omission of toxins from the president’s speech had been unintended or deliberate, saw it as a loophole through which they could continue their work.” They refocused research proposals on toxins instead of pathogens. Meanwhile, the Joint Chiefs of Staff saw an opportunity to re-start toxin production.

Kissinger led another round of deliberations culminating in three options for Nixon to consider, Tucker and Mahan wrote in their case study: Nixon could keep the toxin program; allow chemically synthesized but not biologically produced toxins; or scrap toxins and maintain a defensive research program. Some military officials wanted to maintain the ability to use toxins, others only if they could be chemically produced. Diplomats, meanwhile, favored banning the poisons all together. Approving toxin production, whether through biological processes or chemical synthesis, could, they reasoned, undermine Nixon’s denunciation of bioweapons. It might encourage other countries to develop them or raise obstacles to future negotiations over an international ban on biological weapons.

A Washington Post editorial in January 1970 pointed out the hypocrisy of keeping a toxin arsenal: “Surely the President did not mean that, while a disease induced by living bacteria is out of bounds, a disease induced by a toxin is acceptable. He can scarcely have renounced typhoid only to embrace botulism.”

As is the case with much of his legacy, Kissinger’s decision-making on the toxin issue is shrouded in ambiguity. He’d supported doing away with biological weapons but didn’t want to stop chemically synthesized toxin weapon development; doing so might undermine the US chemical weapons program. “If we are willing to renounce one chemical weapon produced by chemical means, the argument will run, why should we not renounce all chemical weapons,” Kissinger wrote in a memo for Nixon.

Before making a final decision, in the winter of 1970, Nixon, Kissinger and others decamped to Key Biscayne, Florida. There, Kissinger reversed himself and endorsed a halt to toxin weapons development, whether chemically synthesized or biologically produced. The master of “realpolitik”—known in policy circles for pursuing practicality instead of morality—had apparently had a change of heart.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Henry Kissinger, biological weapons

Topics: Biosecurity

He created the Cold War! Many European knows this. He also made a mess in CYPROS! He had a meeting in Brussels with the German chancellor, Macron and other EU after that meeting the world was in chaos with what they created the PLANDEMIC! That meeting in Brussels was printed here in German!