Climate change brings more work, more risk for wildfire workers

By Chad Small | February 16, 2024

Muhammad Khdair (second from left) with other seasonal firefighting workers on a helicopter flyover of the Okanogan region, summer 2023. (Courtesy Muhammad Khdair)

Muhammad Khdair (second from left) with other seasonal firefighting workers on a helicopter flyover of the Okanogan region, summer 2023. (Courtesy Muhammad Khdair)

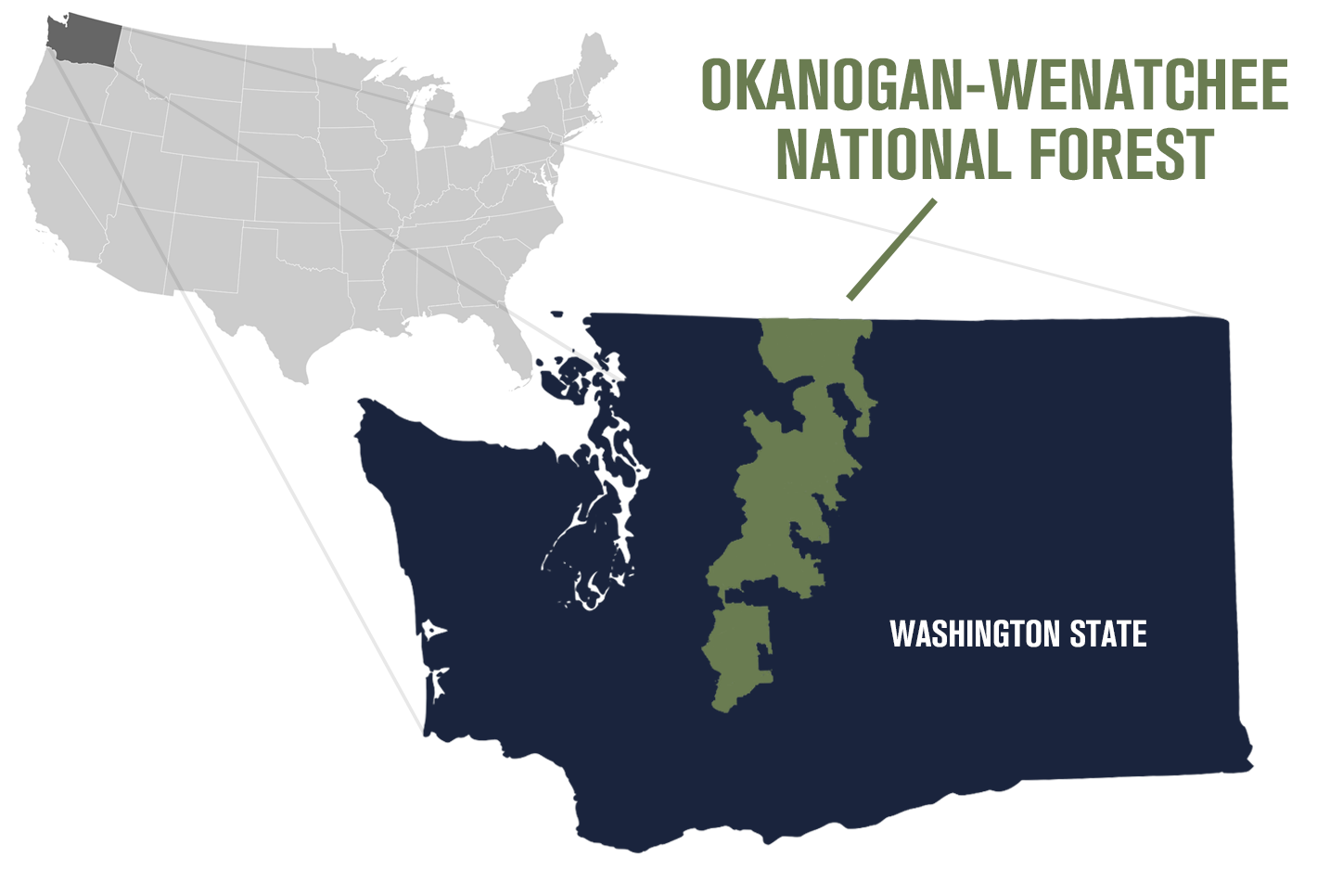

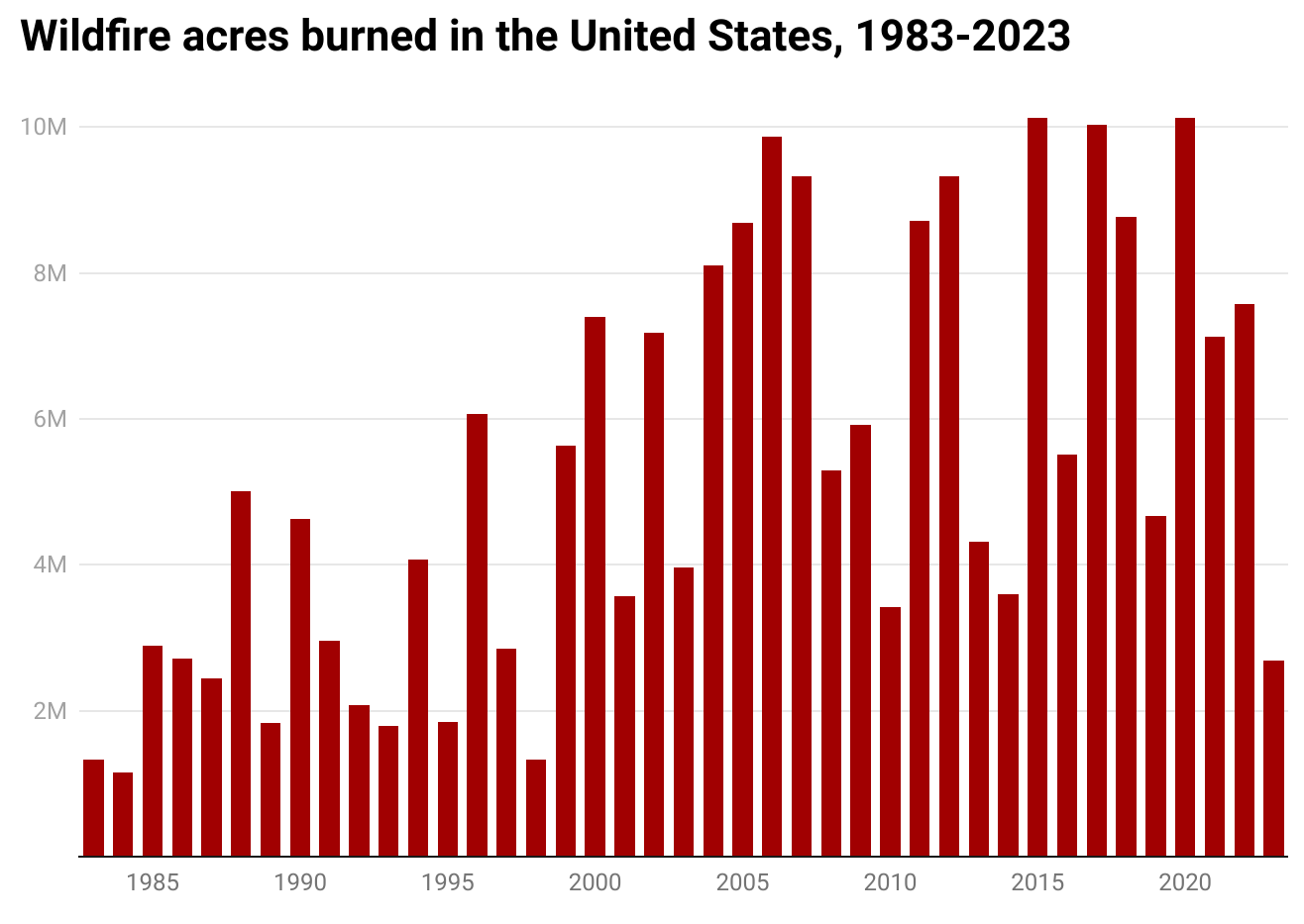

Last year, Muhammad Khdair fulfilled his childhood dream of being a wildland firefighter. He spent the long summer days fighting fires in Okanogan County, in Northern Washington.

The 23-year-old University of Washington student lives 200 miles away from Okanogan, so he booked a hotel for three months. Just a few weeks after his stint as a firefighter ended, he learned that half of the hotel he had stayed in had burned down in yet another wildfire.

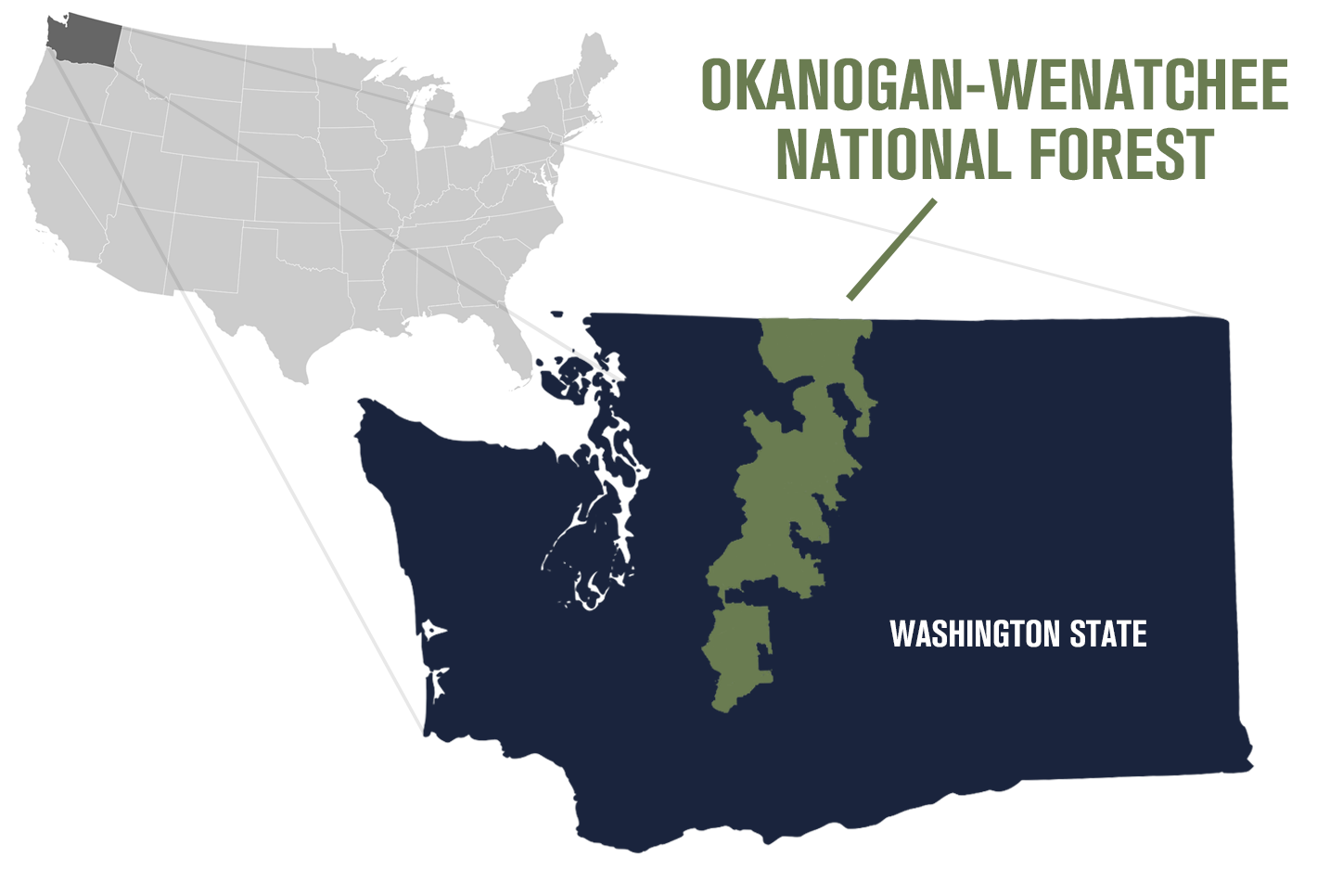

Wildfire season has always been dangerous for people living or working in the wildland-urban interface. But as warmer, drier conditions become more prevalent due to climate change, wildfire season starts earlier and ends later, increasing those risks. In addition to creating even more dangerous living conditions for residents of wildfire-prone areas, these longer fire seasons are upending the systems that federal and state agencies use to try to manage fire.

Wildfire season has always been dangerous for people living or working in the wildland-urban interface. But as warmer, drier conditions become more prevalent due to climate change, wildfire season starts earlier and ends later, increasing those risks. In addition to creating even more dangerous living conditions for residents of wildfire-prone areas, these longer fire seasons are upending the systems that federal and state agencies use to try to manage fire.

Traditionally, two types of fire work (prescribed burning and fire suppression) take place in distinct seasons. This work is primarily carried out by seasonal, temporary workers, brought on for a specific task or period of time. Climate change is blurring these seasonal distinctions. Longer wildfire seasons demand a new, year-round workforce, not only to tackle fires in the next few years, but to do the preventative work to get fires under control in the coming decades.

Fire weather. “We’ve got fires going somewhere in the United States pretty much all the time,” says George Geissler, the state forester at the Washington State Department of Natural Resources. “We just finished with the South having a major fire outbreak late in the fall, and we’ll see a Great Plains lighting off here probably in January and February, like they usually do.”

Wildfire season starts or ends depending on the moisture levels in living and dead vegetation. If this potential fuel is super dry, ignition is easy. If it’s soaked, dumping gasoline on it and lighting it with a match may not cause a fire. Moisture conditions vary seasonally, and even regionally, mostly due to when it rains, and how much it rains.

For the West Coast, the rainiest season is the winter and the driest is the summer. Fire season generally peaks in summer and ends by late fall. But the intensity of rainfall can vary year-to-year. Ernesto Alvarado, associate professor of Wildland Fire Sciences at the University of Washington, notes that El Nino and La Nina can affect how wet or dry a given year is.

These conditions determine if and when fire management agencies can take proactive measures like prescribed burns. Matt Dehr, a wildland fire meteorologist at the Washington State Department of Natural Resources, explains that as conditions get progressively wetter, but not entirely waterlogged, there’s a sweet spot where prescribed burning can happen. On the other hand, Alvarado says “an end of the fire season event” like “one foot of snow or an extreme rain event” ends all fires—prescribed or otherwise—for the year.

Alvarado estimates that between private, state, and federal entities there are 10,000 to 15,000 firefighters hired in the nation every year. Usually, the workforce is largest during the active fire season and shrinks before the prescribed fire season. Some workers are laid off, some have other employment planned, and some, like Khdair, go back to school.

But this system is no longer working as well as it once did. Dehr says that longer fire seasons are “putting a ton of stress and a ton of extra workload onto” an already understaffed workforce.

Dehr and Geissler say the Washington State Department of Natural Resources is starting to transition from a seasonal workforce to a year-round one. The Department of Natural Resources has hired 100 new full-time firefighters to do work ranging from fire suppression to prescribed burns to fuel treatments. While 100 new workers are a good start, it is a small proportion of the several hundred workers that would be needed to meet the demands of a new fire regime. Unfortunately, responding effectively to wildfire in the climate change era is not as simple as opening the government coffers and hiring more people.

A dangerous job. Khdair’s close call in Okanogan County is less an anomaly than a feature of fire suppression work. It’s an objectively dangerous profession that some people might be willing to undertake only for a few months at a time.

Many wildland firefighters live quite far, sometimes hundreds of miles, from fire-prone regions. Some move around from county to county, state to state, following the fires.

“If we have people, and they’re not busy in Washington, but New Mexico is having fires, New Mexico needs them, so we send them. And vice versa," Geissler says.

It can be an isolating job: Wildland firefighters often camp in tents very close to the fires they’re supposed to suppress, but often hundreds of miles from the nearest large town. They can be in these camps for days or weeks, potentially under plumes of smoke. These conditions are physically and mentally taxing. Compared to the general populace, wildland firefighters are at least twice as likely to suffer from depression, anxiety, or suicidal ideations.

“When I was fighting fires in my 20s, nobody cared whether or not you didn’t see your family for a month, and it was a struggle,” Geissler recalls. “You don’t have people that want to get into a world where you don’t have a personal life.”

That’s the main reason Khdair is hoping to land a job as a forestry technician—instead of a wildland firefighter—with the US Forest Service after he graduates this spring. The Forest Service’s office in Western Washington would turn a 200-mile journey to Central Washington into a 40-mile commute for him.

Being extremely far from home can also lead to uncomfortable culture shock. One of Khdair’s coworkers last summer was from Arkansas. “He hates the Northwest,” Khdair says. “[Eastern Washington] is very Republican, but he didn’t like to stay in Washington [because] most of it is liberal.”

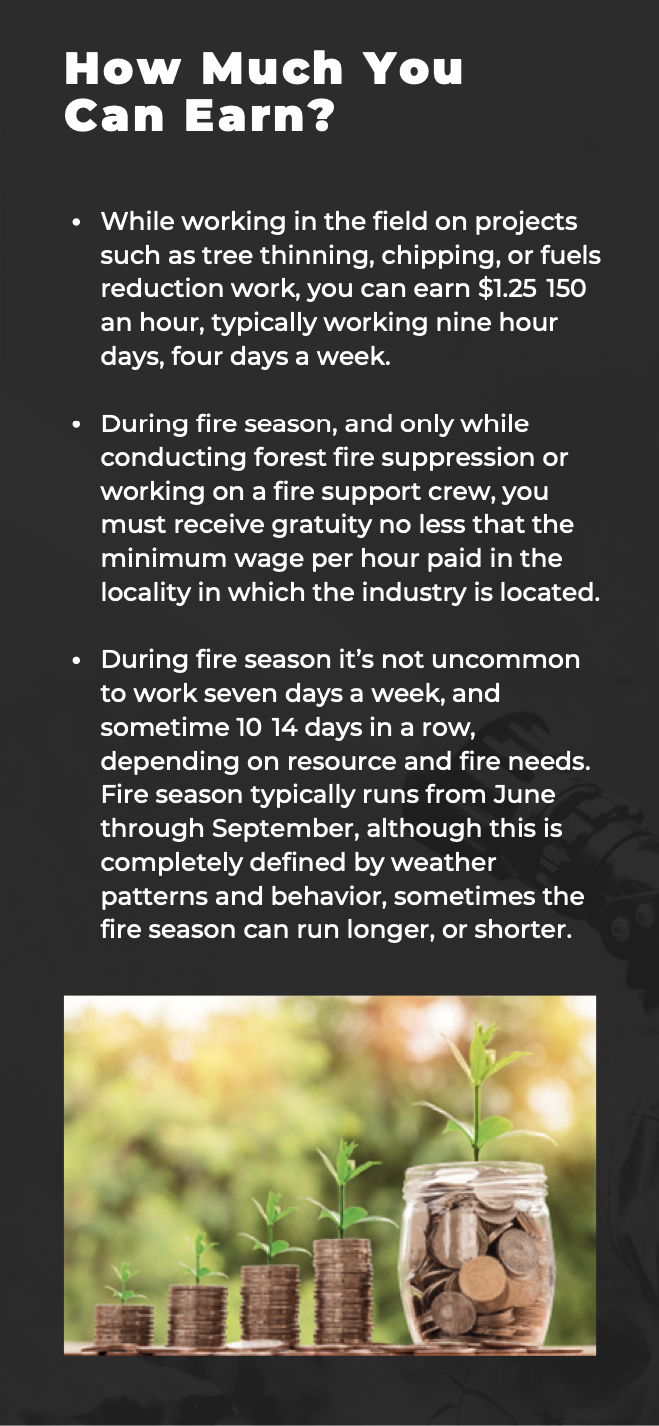

One way to entice people into more direct field work is with pay. The pay can be quite good, depending on the state. Alvarado says that between base pay, overtime, and hazard pay, firefighters in Washington can make around $30 per hour. In a very active fire season, this could translate into $30,000 to $40,000 for a few months of work. Many workers choose this job precisely because they can make a relatively large sum over a short period before returning to their families, other employment, or school.

Like Khdair, a lot of wildland firefighters in Washington are students who use their fire earnings to pay in-state tuition, but that’s not true everywhere. Firefighter pay—often correlated with a state’s minimum wage—can vary drastically from state to state. Nationally, this makes it difficult to have equally successful recruitment. Khdair’s coworker from Arkansas only moved to Washington because a firefighter in Washington can make $10,000 more per season than a firefighter in Arkansas. But if one state raises wages to hire more firefighters, it can suck “the resource from somewhere else,” says Geisler.

“It's not like we’re bringing more people into the system which is really the overall goal,” he says.

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law passed in 2022 has allowed the federal government to intervene somewhat. Like the Inflation Reduction Act, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law was partly aimed at addressing some of the consequences of climate change. It appropriates funding for transportation and infrastructure investments related to climate change, including wildfire preparedness and response. The law allocates funding to support mental health care for wildland firefighters, regardless of where they work.

Agencies like the Washington State Department of Natural Resources are getting creative about recruitment, at times hiring incarcerated workers. Unlike in California, where investigative reporters have revealed that inmates were deployed to wildfires while making less than a third of the state’s minimum wage, the Washington Department of Natural Resources pays incarcerated firefighters the state minimum wage for fire suppression work. Additionally, Washington has a program in place that helps folks get jobs as firefighters when they complete their sentences.

The Washington Department of Corrections and the Department of Natural Resources have also worked out a mutually beneficial solution so formerly incarcerated workers can take jobs as firefighters without violating the terms of their probation.

“With this crew, we can hire them as DNR employees, but we have [the Department of Corrections] working with us,” Geissler says. “They provide the ability to do check-ins and continue to work with the firefighters to get their driver's licenses and everything else.”

Geissler says that this transitional period builds on everything these workers learned and helps them get stable employment. Stable employment post-incarceration is one of the biggest barriers to recidivism.

Building a stable, year-round firefighting workforce is paramount, not just for dealing with current fire seasons, but also to hit longer-term climate goals.

“The ecology of the forest [isn’t] going to change on a year-to-year basis,” Dehr explains. “It is a multi-year—multi-decade, even—process of trying to restore these environments to their historic variability.” This will require burning tens of thousands of acres per year in Washington state. Without meeting those burn targets in the long run, it’s more and more likely we’ll end up seeing the catastrophic wildfires that blanketed cities like San Francisco in smoke in 2020.

“You’re not going to reduce 100 years of missteps in one fell swoop,” he adds.

As the coronavirus crisis shows, we need science now more than ever.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent, nonprofit media organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: climate crisis, climate risk, labor, wildfires

Topics: Climate Change