Hypersonic weapons are mediocre. It’s time to stop wasting money on them.

By David Wright, Cameron Tracy | March 12, 2024

An artist's view of the US long-range hypersonic technology vehicle 2 (HTV-2) as part of DARPA's Falcon project. In 2011, the HTV-2 flight test ended in a failure when it attempted to reach Mach 20 and the Falcon project was discontinued. (Credit: Image courtesy of DARPA)

An artist's view of the US long-range hypersonic technology vehicle 2 (HTV-2) as part of DARPA's Falcon project. In 2011, the HTV-2 flight test ended in a failure when it attempted to reach Mach 20 and the Falcon project was discontinued. (Credit: Image courtesy of DARPA)

Hypersonic weapons are frequently described as having unique, game-changing capabilities because they combine hypersonic speeds (more than five times the speed of sound, or Mach 5) with long-distance gliding at low altitudes (below about 50 kilometers). This has led, for example, to dire warnings that US ships would be “defenseless” against hypersonic attack.

Many countries are currently developing hypersonic weapons, with the United States, Russia, and China leading the pack. The United States is developing several systems designed to carry non-nuclear payloads to distances of a few thousand kilometers. The most advanced US systems are the Army’s Dark Eagle and Navy’s Conventional Prompt Strike, versions of which may be deployed in the next few years. Russia claims to have deployed a long-range hypersonic weapon (Avangard), a short-range ship-based weapon (Tsirkon), as well as a short-range air-launched maneuvering ballistic missile (Kinzhal) that was used in combat for the first time during the war in Ukraine. China has developed two short-range hypersonic weapons: the DF-ZF (WU-14), which it says is operational, and the Xingkong-2 (Starry Sky II), which might start operation in several years.

Most of these weapons are boost-glide vehicles, which are accelerated to hypersonic speeds by rocket boosters and then glide unpowered for hundreds to thousands of kilometers. All three countries are also developing hypersonic cruise missiles, which carry scramjet engines to power them during part of their flight.

Despite this ongoing hypersonic arms race, the specific military utility of these weapons remains unclear.

Analysts have questioned the alleged capabilities of hypersonic weapons, and recent studies further undermine these claims. This makes one wonder why the US government is still devoting billions of dollars to their development and deployment, thereby taking money from other pressing national needs. For the last several years, research and development on hypersonic weapons has consumed several billion dollars annually, corresponding to about 3 percent of all US defense research and development spending. Cumulatively, the United States has spent over $10 billion so far on hypersonic weapons—a figure likely to grow once these weapons enter full-scale production.

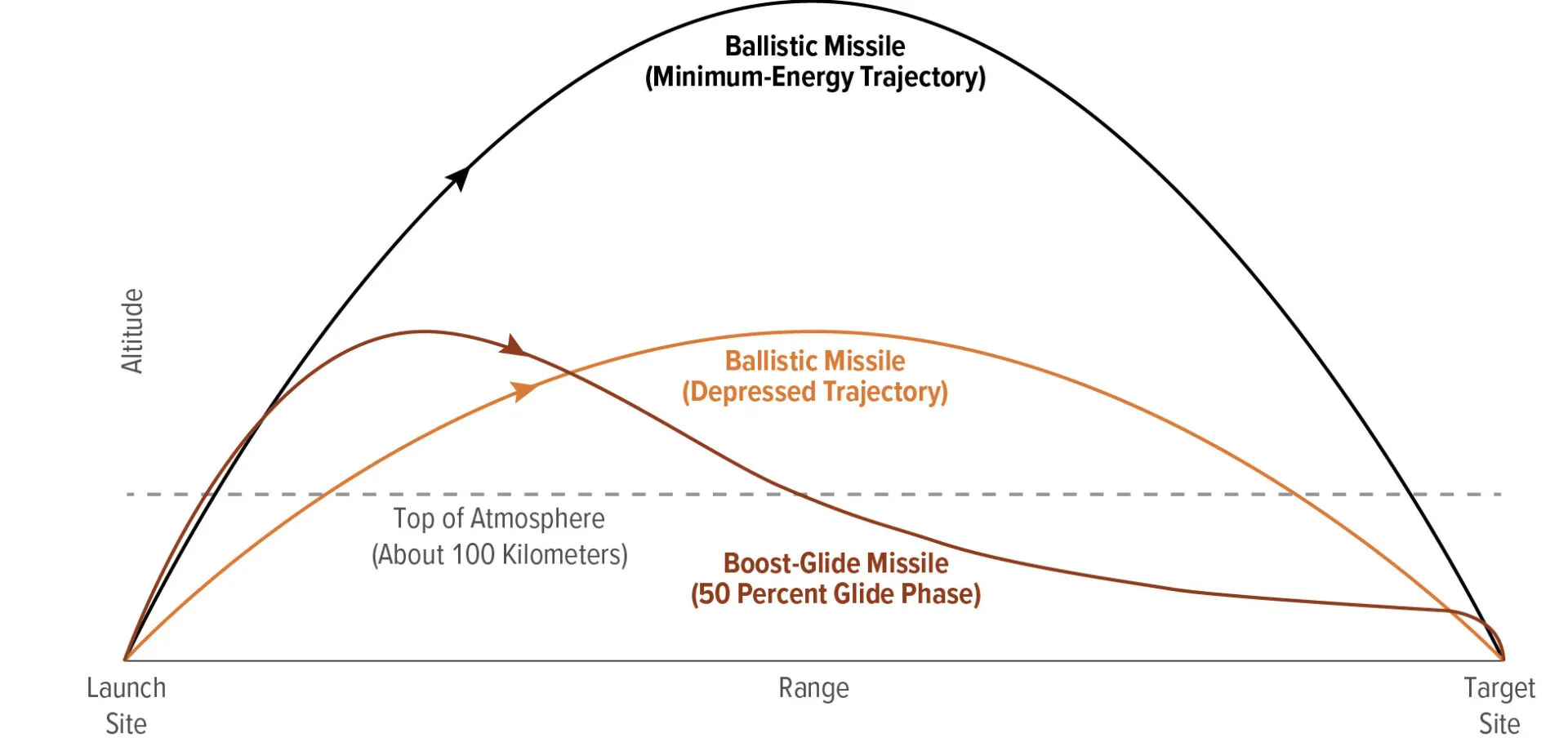

No better flight performance. Existing weapon systems such as ballistic missiles already travel at hypersonic speeds. What distinguishes hypersonic weapons from these weapons is therefore their ability to glide at low altitudes, staying within the atmosphere for most of their flight (Figure 1).

Low-altitude flight potentially offers three main advantages to hypersonic weapons: It makes them stealthy by reducing the range at which ground-based radars can detect them, allows them to maneuver during their long glide phase, and allows them to fly under the reach of long-range missile defenses, which can only operate above the atmosphere. However, low-altitude flight also comes with significant disadvantages—problems that far outweigh many of the purported advantages.

First, flying at high speed through the atmosphere causes significant drag (the mechanical force that opposes an object’s motion through the air). Because drag slows hypersonic weapons, they are no faster—and can actually take longer to reach their targets—than other warhead delivery systems, such as ballistic missiles flown on depressed trajectories.

Low-altitude flight also causes intense, sustained heating of these missiles because of the high density of the atmosphere compared to higher altitudes. The searing heat that hypersonic vehicles are subjected to during glide limits their performance and is the fundamental technological challenge to developing faster and longer-range versions of these weapons. As the aerodynamic heating of a body increases with roughly its velocity cubed, a vehicle gliding at Mach 5 would experience more than 100 times the heating of one gliding at Mach 1 at the same altitude. A further threefold increase in the speed—from Mach 5 to Mach 15—would increase the heating by an additional factor of nearly 30. This intense heating led to the failure of the last test of the US long-range hypersonic technology vehicle 2 (HTV-2), which attempted to reach Mach 20, in 2011.

Ballistic missile warheads experience high heating rates, but only during their short re-entry phase at the end of their flight trajectories, which lasts for less than a minute for a long-range missile on a depressed trajectory, compared to an in-atmosphere glide phase that could last 30 minutes for a long-range hypersonic weapon.

To circumvent the heating problems of long-range hypersonic weapons, the United States and other countries have shifted their focus to versions intended for use in regional conflicts. Theater-level weapon use implies shorter ranges up to a few thousand kilometers, rather than intercontinental trajectories, and required speeds in the range of Mach 5 to 10 rather than the Mach 20 and above envisioned for the HTV-2. A hypersonic weapon starting its glide phase at Mach 10 and gliding for a thousand kilometers at low altitude would still experience intense heating for about eight minutes.

Easily detectable and engaged. Hypersonic weapons are also not as stealthy as advocates frequently claim. To reach their high speeds, they must be launched on large rocket boosters, whose bright exhaust plumes can be seen by currently deployed early-warning satellites. These satellites would be able to detect a possible hypersonic launch and determine the initial direction of the weapon’s flight, which would give a good indication of its target.

Even after launch, these weapons could remain visible. The intense heating of a hypersonic vehicle traveling faster than about Mach 6 to 10 produces a very bright infrared signal during its glide phase that can also be seen by currently deployed early-warning satellites mounted with infrared detectors. This means that even if a hypersonic weapon at such high speeds would change course after launch, existing satellites should be able to detect where it is going and trigger a response to the attack.

Even though low-altitude flight may reduce the range at which hypersonic weapons could be detected by ground-based radars to hundreds of kilometers, that range would still be long enough for them to be tracked and engaged by terminal missile defense systems.

This is important because it means that hypersonic weapons can in fact be intercepted by terminal missile defense systems, which can protect high-value assets like air defenses or ships. The high drag that hypersonic weapons experience during low-altitude flight slows them and would make them easier targets for these defenses to intercept. This means that ships and other assets are less vulnerable to hypersonic weapons than what officials often claim.

Limited maneuvering and no better accuracy. Hypersonic weapons do have the ability to maneuver and change their trajectories during their glide phase, using aerodynamic forces like those that keep them aloft. But the amount of maneuvering these weapons can achieve is typically exaggerated and comes at a significant cost.

The mental image suggested by many descriptions of this maneuvering is of a speedboat weaving its way around obstacles. But, at such high speeds, changing the direction of a missile requires very large forces, and generating such forces would further increase drag and can significantly reduce the speed and range of the weapon. These drawbacks limit how much maneuvering hypersonic missiles can achieve in practice while still reaching useful ranges.

Adding an engine to the weapon to power it during the first part of its low-altitude flight could reduce the speed and range losses from maneuvering. However, since scramjet engines being developed for this purpose are not a mature technology and operating them is notoriously complicated, they will likely be less reliable and more expensive than boost-glide hypersonic weapons that reach high speeds during launch and glide unpowered for most of their flight.

Hypersonic weapons are also touted as being more accurate than current missile technologies. But the same types of guidance and targeting systems being developed for these hypersonic systems can be used on maneuvering missile warheads, which the United States first developed in the Cold War. In addition, these maneuverable re-entry vehicles (MaRVs) fly high enough to avoid the heating problems that hypersonic weapons face during their low-altitude glide. MaRVs can also be made much lighter than hypersonic weapons and therefore require smaller rockets to launch them.

A costly distraction? A recent analysis by the Congressional Budget Office compared hypersonic weapons to MaRVs mounted on ballistic missiles and found that both systems “could provide the combination of speed, accuracy, range, and survivability (the ability to reach a target without being intercepted) that would be useful in the military scenarios [it] considered.” This analysis also showed that hypersonic weapons “could cost one-third more to procure and field than ballistic missiles of the same range with maneuverable warheads.”

Detailed analysis shows that MaRVs launched on ballistic missiles flown on depressed trajectories out-perform hypersonic weapons in many flight scenarios. They would also likely be developed more quickly and perform more reliably than hypersonic missiles.

This makes you wonder whether the US Congress and Pentagon leadership understands this or has been blinded by the exaggerated claims about hypersonic weapons.

In Russia and China, decision-makers may be similarly enthralled by the magical claims about hypersonic weapons put forward by their military advisors without understanding the nuance behind them. Ironically, both countries appear to have stepped up their own hypersonic development programs in part due to US interest in developing new, non-nuclear, long-range missile capabilities following the September 11, 2001 attacks. This program led to the United States to flight test its HTV-2 hypersonic vehicle, although the program was effectively cancelled in 2012 after only a few tests.

There is no doubt that the United States can build and deploy functioning hypersonic weapons, especially ones with relatively low speeds and short ranges. The issue is whether these weapons make any military sense and are a wise use of taxpayer money, independent of whether other countries build them or not.

Exaggerated claims about hypersonic weapons are driving lavish spending on a wide array of hypersonic weapon systems. Yet the hypersonic arms race is likely to have real consequences, increasing international tensions and military spending without enhancing national or global security.

Congress does not seem to be looking critically enough at the US rush to build hypersonic weapons. It should look harder.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Hi. I believe anyone ‘pro deterrence’ is on the wrong side. A large percentage of those who hang their hat at the Bulletin.

Hypersonics are the key for space based interceptors where the interceptors are in low Earth orbit and a hypersonic missile reenters to intercept ballistic or other weapons in their Boost Phase.

This was Michael D. Griffin’s intention when he promoted SpaceX and their Starlink program.