Why I teach my students the racial politics of the Bomb

By John Streamas | March 9, 2024

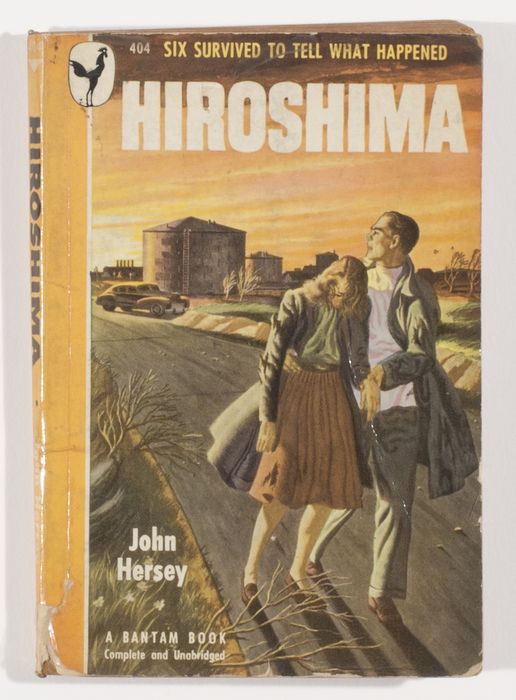

The cover of a Bantam Books 1948 edition of John Hersey's book Hiroshima depicted a white couple fleeing a nuclear explosion, even though the book itself was about Japanese survivors of the Hiroshima bombing. Credit: Museum purchase, 2008, International Center of Photography

The cover of a Bantam Books 1948 edition of John Hersey's book Hiroshima depicted a white couple fleeing a nuclear explosion, even though the book itself was about Japanese survivors of the Hiroshima bombing. Credit: Museum purchase, 2008, International Center of Photography

Teaching college-level ethnic studies, I grow increasingly frustrated by academia’s failure to teach for a better future. This is especially troublesome in fields that, like mine, teach about the history of racism and the manifestations of injustice still around us. One goal of such lessons should be a vision for a better world. How do we achieve a life without racism? Learning the lessons of the past may save us from repeating old mistakes, but it will not save us from new dangers, nor even help us anticipate what those dangers may be.

Though nuclear weapons are obviously one such danger, my students would never guess it by scanning our field’s literature. The prison-industrial complex, xenophobic immigration policy, racial capitalism—these are all nicely covered. But the Bomb might as well have been dropped on a white colonizer, for all the attention it gets from ethnic studies. Many people deny that any link exists between racism and the Bomb—they angrily shut down discussion of a link—and here I will not belabor my claim except to note that, within days of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, writers of color casually commented on a connection. Less than two weeks after Hiroshima, Langston Hughes, writing for the Chicago Defender in the voice of his fictive character Simple, said the United States waited until the war was over in Europe to try out nuclear weapons on colored folks. In her 1999 book The Cost of Living, Arundhati Roy called the Bomb the whitest of weapons.

Even British historian Matthew Jones, crafting in his book After Hiroshima a vigorous and mostly nuanced defense of the Bomb, resorts to a logic by which “total war” can justify any atrocity, but this unwittingly equates the Bomb with Auschwitz. British historian Lawrence Freedman and Japanese-British historian Sacki Dockrill argue, in their 2010 essay “Hiroshima: A Strategy of Shock,” for a “shock and awe” logic by which the United States could say to Japan, “We will destroy you before you can destroy us;” then they approvingly quote General George C. Marshall’s racial construction of the Japanese people as “fanatical” and needing extermination.

In a 2018 essay in the Bulletin, Erin Connolly and Kate Hewitt reported that an informal survey of students in American high schools and colleges near Manhattan Project sites found that they know little or nothing about nuclear weapons. The authors argued that these students can and want to learn, and that they need to. The essay emphasized history and geography as potential disciplines for this learning. If high schools heeded their advice and taught the basics of nuclear war, then my work in college-level ethnic studies, linking the Bomb to racism, would surely be easier and much less controversial.

I would teach that the Pacific War historians who are most knowledgeable about the Japanese, such as John Dower and Naoko Wake, cite a multitude of factors leading to the Bomb’s usage and place racism far down their lists, but they do assign it a place. And the naming of that place teaches considerably more than best-selling ethnic studies texts do.

So why do students enrolled in both introductory and even upper-level ethnic studies courses learn little or nothing about the racial politics of the Bomb? Few people want to talk about racism in connection with anything. Yet I believe the main reason is that even fewer want to talk about the Bomb. That kind of talk confronts us with The End, the absolute foreclosure of a future.

If teachers do not teach it, and students do not inquire into it, then, as long as the Bomb sits in siloes, the link I am making is not granted any urgency. If a future comes, then we know the Bomb has not fallen. If it does not, then what can it matter? Who will be left to care? Yet it does matter. To plant in students’ minds a vision of a glorious future in which we have eradicated racism and sexism and all other social injustices is to create a false security unless we also eradicate the Bomb. A racism-free world is great, but not if the Bomb still exists to wipe it out.

In his 1914 novel The World Set Free, H. G. Wells, better known for The Time Machine and The Invisible Man and The Island of Dr Moreau, envisioned not only nuclear blasts but even radiation illness, and he imagined a postwar in which chastened communities of survivors would abolish their bombs and live in quiet (even if not perfectly blissful) peace. But in Wells’s world, deterrence is achieved not by having the Bomb but by having used it, with survivors shamed into disarming. In all ways, they are pacified, but they alone enjoy the peace. If this is truly a “world set free,” the cost is the annihilation of billions. To my knowledge, the novel is seldom if ever assigned in schools, and while its literary inferiority is probably the main reason, I suggest that a secondary reason is that teachers would prefer not to confront students with a story of nuclear war even if it ends with chastened and peaceful survivors.

This is understandable. In their book Hiroshima in America, Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell note that until the late 1980s, Americans told polltakers that their greatest existential fear was death by nuclear war. Then the Cold War ended. But nuclear calamity was not replaced by more abstract, inchoate fears such as climate collapse; it was subsumed inside those new fears. It remains, as a related threat. In my field, we teach about and research this family of fears—which includes fears of the racism inherent in policing, incarcerating, housing, delivering healthcare, and even schooling—but we neglect this lone family member, nuclear war. It is treated as though it is only tangentially related to racism or not related at all.

In the United States, teachers have enough trouble already, with conservatives waging war on our work and often winning by legislating an end to Critical Race Theory and diversity programs and affirmative action. When even many liberals deny a link between the Bomb and racism, how much more fiercely would those same conservatives work to eradicate any programs that hinted at a link?

Should teachers even bother to teach the Bomb’s implications for students’ future? Most of my students of color come into my classes convinced that racism will never end, so why should I add to their worries the seemingly less immediate threat of nuclear war? I can show them that nuclear policy, as Jessica Hurley writes in Infrastructures of Apocalypse, designates Blacks as the first and worst American victims of the Bomb—urban planning having located Black neighborhoods in vulnerably targeted places—or that, as Joseph Masco and Traci Brynne Voyles demonstrate in their research on the American Southwest and Valerie Kuletz explains in her work on the Pacific, the mining of materials such as uranium victimizes indigenous peoples globally. Understandably, however, students’ more immediate fear is that they will be racially profiled by cops, denied jobs or promotions, or charged racially elevated rents.

Of course the future matters, and of course my students want it to come. Even if the link between racism and the Bomb is minuscule, abolishing racism necessarily involves nuclear disarmament. A warmonger might call it “killing two birds with one stone.” Unfortunately, the reverse is not necessarily true. Abolishing the Bomb will not abolish all racism, but it will reduce the number of threats to people of color by one—a huge one.

Still, because the literature in my field ignores nuclear war, I can devote only a small amount of class time to it. This is why I hope my own research will add to the work of the aforementioned critics, and that their work and mine might earn some attention in the field’s leading texts, and that maybe some of my students will add still more scholarship and advocacy.

Then surely the second-biggest benefit—after eliminating a threat of annihilation!—will be the crafting of a vision for the future. Otherwise, to say that “the journey is more important than the destination” is to ignore the possibility that the destination is extinction, and to ignore “the prize” on which civil rights activists keep their eyes. That prize is not only justice and peace, but also life itself.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Hiroshima, bomb, ethnic studies, racism

Topics: Nuclear Weapons, Opinion

Oh, so the US dropped the bomb on the two Japanese cities because they wanted to experiment with it against people of color. Wow!! So I guess the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour to experiment about bombing white people. Oh, and the rape of Nanking was an experiment against Chinese?

Where do you get off on such bizarre thinking?

I would teach my 7-8th grade middle school students about the ‘Bomb’ within my physics curriculum for years back in the 1980’s. ‘Atomic Cafe’ and other VHS tapes at the time were very helpful to convey the senselessness of MAD’ and to give them an ethical perspective on real history. Those kind of classroom days are long gone now with lesson material taken out of the teacher’s hands as we follow an exact lesson day by day with no enrichment allowed by a creative teacher.

Hi, Mr Petnuch. Thanks for your note. I would like to ask, if you don’t mind, did your middle-school students get it? That would be my only concern about teaching nuclear issues in K-12. I think the films are a great idea. I’ve shown “Radio Bikini” in my classes, and the gradual revelation of the sailor’s radiation illness is extremely sobering to students. I wish you were still able to teach as you would like. Thanks again.