June 20, 2024

In 2006, a group of preeminent scientists met for a two-day conference at the NASA Ames Research Center in California to discuss cooling the Earth by injecting particles into the stratosphere to reflect sunlight into space.

At some point, one of the conference rooms became overheated.

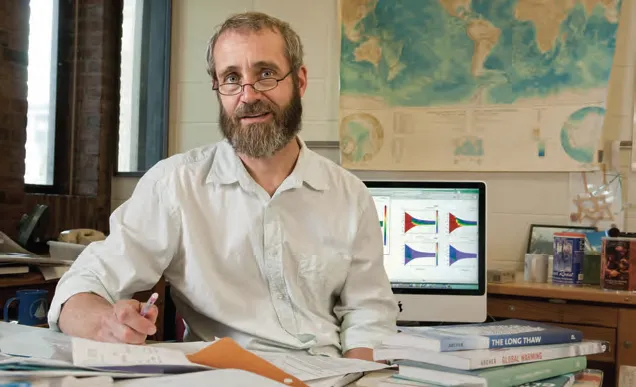

“The room was getting kind of hot, and somebody went over to the thermostat to try and fix it,” recalled Alan Robock, a Rutgers climatologist who was in attendance. “And they couldn’t adjust it. And so many people didn’t understand the irony that you can’t control the temperature of a room, but you’re talking about controlling the temperature of the whole Earth.”

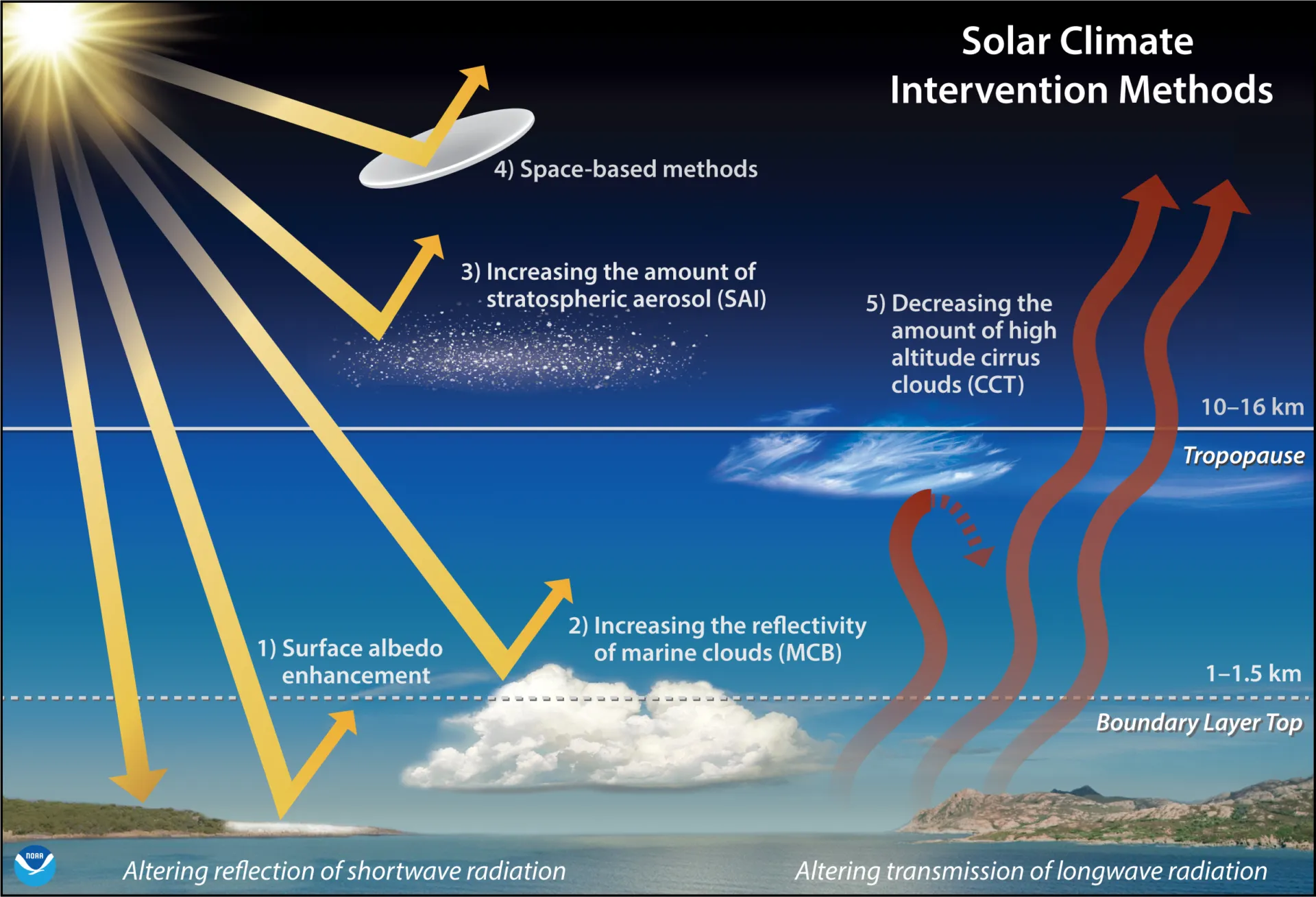

Solar geoengineering—also called solar radiation management or solar radiation modification—was then and is now a fraught subject. Many experts and nonexperts alike consider the idea of deliberately mucking about with Earth’s climate systems to counteract centuries of mostly accidental mucking about in Earth’s climate systems ethically dubious and potentially highly dangerous.

And yet: Last year, the global average temperature was almost 1.5 degrees Celsius warmer than the pre-industrial average, due to the vast amounts of heat-trapping carbon dioxide that humans have added to the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels. This warming is responsible for a wide range of climate impacts, from more extreme storms and longer heat waves to increased precipitation and flooding as well as more severe droughts and longer wildfire seasons.

As the climate crisis has escalated, some experts have suggested that drastic measures like solar geoengineering may eventually become necessary and so should be researched now.

Would it work? In 1991, the eruption of Mount Pinatubo spewed 17 million metric tons of sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere, which cooled the Earth by roughly 0.5 degree Celsius (0.9 degree Fahrenheit) for about a year. After the Tambora volcano in Indonesia erupted in 1815, parts of Europe and North America saw a “year without summer.” Scientists have looked to those events to try to understand what might happen if humans deliberately released sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere. But there is a world of difference between studying naturally occurring volcanic eruptions and intentionally modifying the amount of solar radiation that reaches Earth’s surface.

Solar geoengineering is a controversial area of research for numerous reasons. In 2008, Robock penned an article for the Bulletin on the 20 reasons solar geoengineering could be a bad—possibly even catastrophic—idea; a more recent version expanded the list to 26.

Introducing particles like sulfate aerosols into the stratosphere could create a plethora of new and unpredictable problems. Possible negative impacts may include changing regional weather patterns—creating or shifting areas of drought or regions that receive extreme precipitation—or altering tropospheric chemistry and ocean circulation patterns. Partially blocking the sun’s rays could interfere with normal plant processes and reduce agricultural yields. Adding sulfate aerosols to the stratosphere would degrade the ozone layer (thereby increasing global cancer rates) and increase acid rain. The potential effects of solar radiation management are so large and wide-ranging as to implicate almost every aspect of life on the planet.

Even in best-case scenarios, it would be only a partial stopgap. Solar geoengineering, for example, does nothing to ameliorate ocean acidification, which occurs when the ocean absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. This acidification threatens ocean life like oysters, clams, sea urchins, corals, and the calcareous phytoplankton that help make up the foundation of the marine food web on which much of humanity depends.

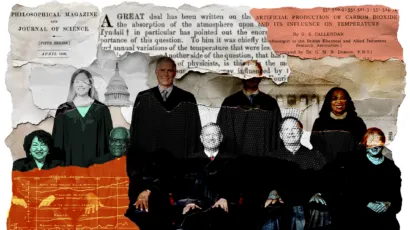

Also, many experts agree, global governance structures are profoundly ill-equipped to deal with the kinds of questions solar geoengineering will raise: How much cooling is the right amount? (Wouldn’t Russia want things a bit warmer, and India somewhat cooler?) Who benefits, and who doesn’t, and who decides? How would disputes about the negative impacts of any geoengineering regime be adjudicated? The type of world-spanning, long-term regulatory scheme required to institute and manage solar geoengineering has no precedent in human history.

Some have argued that merely conducting research could inspire rogue actors to take things into their own hands, with potentially disastrous geophysical and geopolitical results. Then there is the moral hazard argument against geoengineering: If humans began cooling the Earth with solar geoengineering, wouldn’t that give citizens a false sense of security—and companies an excuse to pump the brakes on decarbonization of energy systems and proceed with fossil-fuel-burning business as usual?