Biden focused on strategic stability. His successor should embrace arms control

By Stephen J. Cimbala, Lawrence J. Korb | September 13, 2024

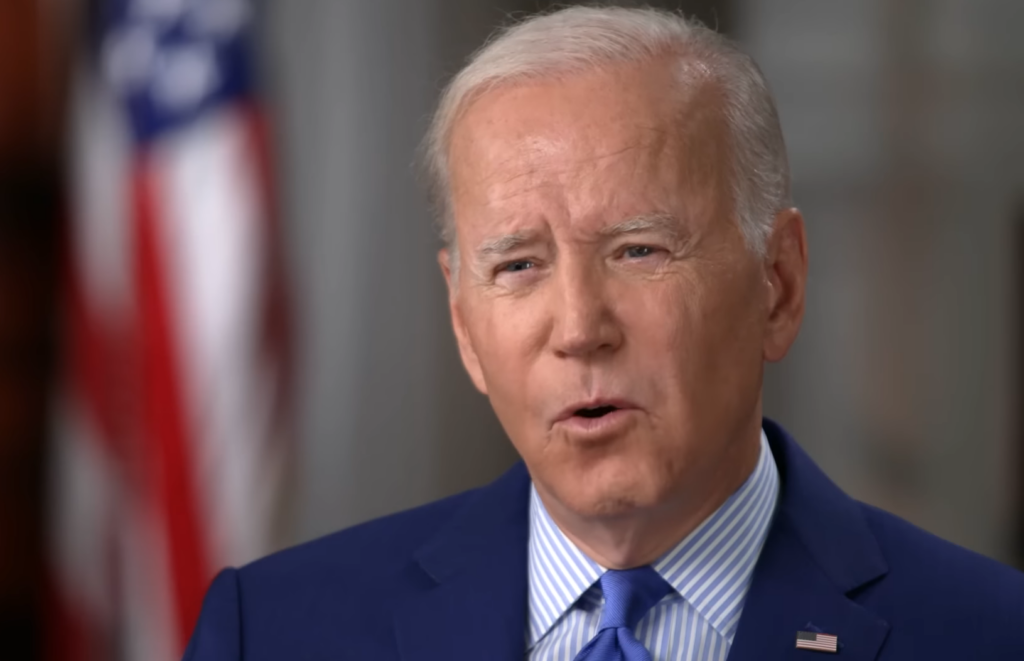

A screenshot taken from President Joe Biden's interview for CBS' 60 minutes broadcast on September 17, 2022, during which he warned Russian President Vladimir Putin against using tactical nuclear or chemical weapons after a series of military losses in Ukraine. "Don't. Don't. Don't. It would change the face of war unlike anything since World War II," Biden said. (Credit: CBS)

A screenshot taken from President Joe Biden's interview for CBS' 60 minutes broadcast on September 17, 2022, during which he warned Russian President Vladimir Putin against using tactical nuclear or chemical weapons after a series of military losses in Ukraine. "Don't. Don't. Don't. It would change the face of war unlike anything since World War II," Biden said. (Credit: CBS)

As the Biden administration prepares to depart office, an assessment of its policies with respect to nuclear issues and future challenges become increasingly important. President Joe Biden will be succeeded by either Vice President Kamala Harris or former President Donald Trump. Either future president will have to pick up the ball where Biden left it. But in many ways, the ball isn’t rolling as smoothly as it should.

Three elements of Biden’s nuclear policies promise to particularly challenge his legacy: the usefulness of New START as a prospective framework for organizing US-Russian strategic nuclear arms control; the implications of China’s apparent determination to become a third nuclear superpower; and the potential game changers to a (so far) successful nuclear nonproliferation regime.

These perspectives could determine whether the nuclear legacy of Biden and his administration can last—or if events will outrun it in a matter of days or weeks.

New START’s possible disappearance. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has created a hiatus in Russian-US negotiations on their bilateral New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), and Russia has officially suspended its participation in the treaty (although Russia has stated its intention to remain within current New START limits on the numbers of treaty-permitted operationally deployed launchers and weapons). In addition to New START paralysis, the growing military alliance between China and Russia, combined with China’s apparent intention to become a third nuclear superpower, holds the potential to accelerate the three-sided nuclear arms race and encourage the rise of additional nuclear weapons states. In this context, it is not clear if current Russian and US strategic nuclear forces lend themselves to renewal and continuation of New START prior to its scheduled expiry date of February 2026. An extended or reborn New START will have to meet criteria for deterrence stability, including crisis and arms race stability.

The United States and Russia signed the New START agreement in 2010 under President Obama and agreed in January 2021 to extend it until February 2026. New START limited each state to a deployment of no more than 1,500 operationally deployed warheads on a maximum of 700 deployed intercontinental launchers (intercontinental ballistic missiles, or ICBMs; submarine launched ballistic missiles, or SLBMs; and heavy bombers).[1] Periodic on-site inspections and other means of monitoring and verification supported transparency with respect to each side’s activities under the New START regime. Russia’s war against Ukraine beginning in February 2022 poisoned the atmosphere for nuclear arms control, already encumbered by prior withdrawals of both the United States and Russia from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty). In addition, President Vladimir Putin and other Russian leaders repeatedly issued threats of possible nuclear first use in response to NATO escalation of its support for Ukraine.[2] Russia eventually suspended its participation in New START talks, although it has not taken the additional step of abrogating the treaty.

The United States contends that Russia’s suspension of its activity related to New START is legally invalid, and in response in 2023 the United States adopted four countermeasures: (1) no longer providing biennial data updates to Russia; (2) withholding from Russia notifications related to treaty-accountable items such as missiles and launchers as required under the treaty; (3) refraining from facilitating inspection activities on US territory; and (4) not providing Russia with telemetry on US ICBM and SLBM launches.[3] This protocol stalling by both sides leaves the status of New START in limbo unless or until more favorable political winds supersede the present stalemate. New START could, in other words, slowly disappear into the mists of diplomacy and political inertia, with no apparent substitute framework for bilateral strategic arms limitation over the horizon.[4]

The eclipse of New START is of course neither necessary nor desirable.

The United States and Russia have considerable Cold War and post-Cold War experience in nuclear arms control and other efforts to limit the nuclear arms race. Politics, including disagreements and involvement of either party in proxy wars, have frequently marked the atmosphere for discussion of nuclear issues between the two major nuclear powers: US-Soviet and then US-Russian nuclear discussions and arms control negotiations took place during the large-scale US military involvement in the Vietnam war; despite wars in the Middle East in which the Americans and the Soviets supported opposite sides; during the Soviet war in Afghanistan in the 1980s; and, despite the hothouse atmosphere in the same decade in Europe surrounding competing NATO and Soviet deployments of intermediate range ballistic missiles and the challenges in managing the Cold War endgame. Despite skeptical voices in Kiev, Moscow, Brussels and Washington, sooner or later the currently ongoing war in Ukraine will have to be ended by a negotiated settlement that, likely or not, will involve concessions by both Ukraine and Russia.

Letting New START lapse without a successor regime would be also a tacit encouragement to existing nuclear weapons states to increase their reliance on deterrence self-help in Europe (and also in the Middle East and Asia). And the absence of ongoing nuclear arms control is a fast track into additional nuclear arms racing.

Some argue that when political relations between states are unfriendly then arms control is impossible and that when they are friendly arms control is unnecessary. But this argument falls short of explanatory and prescriptive power. Arms control is more necessary between potential rivals than it is among members of the same alliance or other security community. No military planner in NATO is worried about the nuclear arsenals of Britain or France, and few if any members of that alliance fear that other currently non-nuclear members of NATO will become a nuclear weapons state any time soon. This is especially the case so long as the US nuclear guaranty of extended deterrence continues to apply to any and all NATO members threatened by nuclear coercion, first nuclear use, or first nuclear strike.

In this regard, Putin’s repeated invocation of nuclear coercion to support Russia’s war in Ukraine is counterproductive to his aim of ending the war in Ukraine on the most favorable possible terms for Russia. Repetitive threats of nuclear first use that are not followed by any actual changes in Russian military operational behavior (of the kind that are “telltales” for intelligence collectors in the United States and NATO) simply immunize opponents and other observers against additional fears of crossing the nuclear threshold. Such behavior “normalizes” nuclear coercion in a way that is very dangerous, creating doubts about any firebreaks that may exist between escalation of conventional war fighting and nuclear first use. The result could be a NATO or Russian quantitative leap in long-range missile strikes or other seemingly tactical enhancements that are perceived by the other side as qualitative jumps into the destruction of strategically vital targets—and, thereby, considered to deserve of a nuclear response. For examples, NATO missile strikes against vital Russian targets in Crimea or Ukrainian air strikes using US-built F-16 aircraft against targets inside Russia could signal to the Russian leadership a willingness by NATO to escalate conventional war beyond previously understood boundaries.

As Nikolai Sokov has pointed out, while the Ukrainian invasion of Kursk resulted in a battle with Russian forces that probably will not lead to Russia using nuclear weapons against Ukraine, Russian escalation against NATO countries cannot be ruled out.[5]

Along with the concern about Russia’s dubious mixture of conventional war fighting and nuclear coercion comes the additional concern about Ukraine’s expectation that NATO and Ukraine will inflict a strategic victory against Russia and, at a minimum, expel Russia entirely from territories now occupied in eastern and southern Ukraine. However, repeated claims that Ukraine could have won the war on the ground had NATO and the United States supplied sufficient numbers of long-range weapons in good time fly in the face of operational realities: Russia outnumbers Ukraine in available numbers of service personnel and in the industrial sinews for protracted conventional warfare, including a robust and growing military industrial base. Admittedly Russia’s military performance in the early stages of the war was disappointing in terms of its inflated initial war aims, insufficient preparedness for modern combined arms combat, and poor leadership at all levels. But with the experience of the last two and a half years, Russia has improved its command of the operational-tactical battlespace and its ability to integrate modern technology (including, drones; Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance, or C4ISR; precision strike; and air-ground coordination) with traditional principles of ground combat and fire discipline.

Of course, the Ukrainians, too, are fast learners.

Ukraine’s lunge into Russia’s Kursk oblast, which started on August 6, 2024, caught Russia unprepared for a surprise attack intended to divert Russian troops from other fronts, embarrassing Putin and his military leadership and leading Ukraine to seize Russian territory as a potential bargaining chip for future negotiations.[6] Ukrainian forces showed superior command and control for combined arms battle and brought about the first incursion into Russian territory by a foreign power since World War II. But Ukraine’s temporary success did not change the fundamentals of military combat under modern conditions: Other things being equal, time favors Russia by wearing out the Ukrainian forces and the collective NATO will to resist—provided Putin does not stumble into an ill-advised nuclear first use that blows the lid off prior expectations. Of course, Putin has already committed a political blunder by bringing about the enlargement of NATO into a membership of 32 countries, with the accession of Finland and Sweden in 2023 and 2024, respectively), thereby increasing the borders between Russia and NATO member states that are possible locations for inadvertent, ill-advised, or otherwise miscalculated escalation.

With present or foreseeable strategic nuclear forces within this decade, the United States and Russia can maintain credible deterrence along with crisis stability (first strike stability) and arms race stability.[7] New START deployment limitations, counting rules, and erstwhile provisions for monitoring and verification, including on-site inspections, may also provide valuable experience if and when China decides to engage in trilateral arms control. A missing element in this prescription is the decision by both Washington and Moscow to withdraw from the INF treaty, leaving open the door to future deployment of intermediate range, nuclear armed missiles that could return us to the uncertainties of the latter 1980s with respect to nuclear deterrence challenges. In addition, a follow-on treaty to an extended New START could expand coverage to include bans or limits on some long-range systems not now covered by treaty agreement (such as Russia’s Burevestnik nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed cruise missile and its Poseidon nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed long-range torpedo) or impose total warhead caps on all nuclear weapons, including nondeployed and nonstrategic warheads.[8]

China’s rising nuclear ambitions. In recent years, US defense officials and most expert analysts have come to the conclusion that China’s plans to modernize its strategic nuclear deterrent and expand its size and diversity may seek to equal the forces of the United States and Russia. A 2023 study group convened by the Center for Global Security Research at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory noted that:

For the first time in its nuclear history, the United States faces two major power adversaries armed with large and diverse nuclear forces, capable of challenging the United States and its allies in a limited regional war fought with conventional forces, and bound together by a hostility to US-led global and regional orders and the resolve to bring about their end.[9]

Similarly, the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States warned that US strategy should no longer treat China’s nuclear forces as a “lesser included threat” and that the United States needs a nuclear posture capable of deterring both countries, simultaneously.[10] In addition, the US Defense Department has projected, with respect to China’s growing nuclear capabilities, a consistent pattern of improvement:

[The Defense Department] estimates that [China] will probably have over 1,000 operational nuclear warheads by 2030, much of which will be deployed at higher readiness levels and will continue growing its force to 2035 in line with its goal of ensuring [The People’s Liberation Army’s] modernization is “basically complete” that year, which serves as an important milestone on the road to [Chinese President Xi Jinping]’s goal of a “world class” military by 2049.[11]

The Defense Department is considering options to increase the number of nuclear weapons launchers and warheads available for uploading if necessary. Vipin Narang, who until recently served as acting assistant secretary for space policy and was also responsible for nuclear, missile defense and cyber policy, noted that the United States is “exploring options to increase future launcher capacity or additional deployed warheads on the land, sea and air legs” that could offer national leaders “increased flexibility, if desired, and executed.”[12] In addition, earlier remarks by Pranay Vaddi, senior director for arms control, disarmament and nonproliferation at the National Security Council, indicated that senior Biden officials would be taking a fresh look at the assumptions behind US nuclear modernization in view of the changed international security environment, including Russia’s efforts to develop a satellite carrying a nuclear weapon, China’s accelerated nuclear buildup, and North Korea’s continuing expansion and improvement of its nuclear ballistic missile and conventional force capabilities.[13]

Even if experts seem to agree that China will attempt to join the United States and Russia in forming a trilateral club of nuclear superpowers by the mid-2030s or so, does it mean that the United States should plan its future nuclear modernization on the assumption of arms racing against the sum of both Russian and Chinese nuclear expansion?

One argument for additional US force building would be that, for credible deterrence against both Russia and China, the United States must maintain capabilities for damage limitation against either or both. Capabilities for damage limitation against larger numbers of Russian and Chinese nuclear missiles would theoretically require more US ICBMs or other early launching and fast flying components of the strategic nuclear triad. Increased numbers of Russian and Chinese hypersonic weapons might create additional pressure for US compensation in damage limitation. However, for others like Henry Sokolski, the United States might prefer to take another approach that is less potentially destabilizing:

Rather than aiming to significantly expand the US nuclear arsenal to achieve a high level of damage limitation, the United States should place higher priority on making it more difficult for China or Russia to disable or destroy US and allied nuclear forces. This recommends transitioning all its siloed intercontinental ballistic missiles to mobile platforms and camouflaging and decoying them along with US strategic submarines and bombers. Alternative basing on commercial planes, trains, and ships also should be explored. For key fixed targets, active defenses and hardening may be necessary.[14]

But even the Sokolski approach is not without risk because mobile platforms and camouflaging could be destabilizing as it may increase the risk of misinterpretation and miscalculation in a crisis. Other approaches to damage limitation could include the next generation nationwide ballistic missile defenses that could substantially defeat or thin out prospective attackers’ nuclear first strikes, including defenses capable of boost phase or post-boost intercept.[15] Existing technologies for ballistic missile defenses or integrated air and missile defense will improve incrementally over the next decade or so, but defenses that could provide continental-wide protection against large scale attacks would require a qualitative leap forward in technology. On the other hand, point defenses to protect components of the US strategic nuclear retaliatory force are within reach of currently available air and missile defense systems.

By all evidence, addressing the prospective challenges posed by a rising nuclear China together with Russia will require both offensive and defensive countermeasures for damage limitation and for deterrence stability. But the United States will need to engage in nuclear arms control too—although perhaps at two levels, through explicit agreements between the United States and Russia, and tacit understandings among Russia, China, and the United States, based on a whirligig of conference diplomacy and military-to-military expert exchanges.

Nonproliferation. One of the success stories for international relations since the Cold War has been the robustness of the nuclear nonproliferation regime. Future challenges to that regime will test its resilience.

One such challenge is the current status of Iran as a threshold nuclear weapons state.

Iran has at least three overlapping political objectives. First, Tehran sees itself as the potentially dominant power in the Middle East, in competition with Saudi Arabia (and possibly Turkey). Second, Iran wants to push back against the US military presence in the region, primarily by waging war through its proxy terrorist organizations. Third, Iran wants to destroy Israel or weaken it to the maximum extent possible, by proxy war and other means. Iran does not necessarily desire a nuclear weapons capability for the purpose of launching a nuclear first strike on Israel. The purpose of an Iranian bomb, rather, would be deterrence against nuclear coercive diplomacy or first use by Israel, in order to provide more room for conventional military adventurism on the part of Iran. Iran could “use” the bomb, without actually firing it, in other ways: either by demonstrative testing of nuclear capable launchers; demanding a droit de regard on regional issues in opposition to the views of Israel, the United States, or US-friendly Middle Eastern powers; or, by tacit or explicit threat to make available nuclear materials and know-how to their proxies in Gaza, Lebanon, and Yemen.

In 2015, Iran and the P-6 states (the five Permanent Members of the UN Security Council and Germany) signed the Iran nuclear deal (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA). The agreement placed restrictions on Iran’s civilian nuclear program in return for sanctions relief. The JCPOA went into effect in January 2016, but President Trump withdrew the United States from the agreement in 2018. After this, the Biden administration has sought to renew the agreement during several years of negotiations; but the parties have remained far apart. Hamas’ attack on Israel on October 7 and the resulting war in Gaza have exacerbated already tense relations between the United States and Iran, as did Iran’s continuing support for Houthi rebels in Yemen and other proxy attacks on US forces deployed in Iraq and Syria. Israel continues to define Iran’s nuclear weaponization as unacceptable from the standpoint of Israel’s national security and survival. And Iran continues to position itself for the jump from “almost” to “actual” weaponization in a matter of months. And, of course, were Iran to actually join the nuclear club, Saudi Arabia has already indicated that it would have no choice but to do likewise. And other regional actors, including Turkey and Egypt, could follow.

Another challenge is North Korea, for which two issues loom large in the near future.

First, North Korea’s ambitions will take it beyond the small nuclear deterrent that has previously served as the backdrop of its aggressive regional policy. US officials estimate that North Korea now has more than 60 nuclear weapons and enough fuel for many more. The size of North Korea’s expanded arsenal is approaching that of Israel and Pakistan. Second, the United States must now assume a higher level of coordination among Russia, China, and North Korea with respect to their strategic planning. Last month, Narang warned of the “real possibility of collaboration and even collusion between our nuclear-armed adversaries” and noted that “[i]t is possible that we will one day look back and see the quarter-century after the Cold War as nuclear intermission.”[16]

With respect to the issue of coordination, military planning and joint training exercises pose new challenges. Russia and China of late have increased the frequency and intensity of their military exercises with respect to conventional warfare, but how far this extends into the protocols for nuclear deterrence or nuclear use is more uncertain. There is obvious disagreement between Russian and Chinese political leadership with respect to public discussion of nuclear employment policy. Putin’s repeated references to the possibility of Russian nuclear first use in Ukraine or elsewhere in Europe have received no public support from China, and President Xi has publicly expressed his opposition to any use of nuclear weapons in that conflict. China has no interest in being drafted into a game of nuclear chicken between NATO and Russia.

Another potential obstacle to nuclear jointness in Russian and Chinese military planning is the latent possibility of future conflict between the two states over other issues, including territorial disputes and hegemony in Central Asia. There is also the issue of who is now the senior and who is the junior partner in their relationship. In the past, Russia was assumed to be the senior partner in military capability, and China the leader in economic size and potential. As China’s nuclear arsenal grows to a size more approximate to that of Russia and-or the United States, its larger military ambitions may collide with those of Russia despite their shared opposition to US global leadership. Russia and China may also probably be wary of embracing North Korea’s extremist policies with respect to South Korea, Japan, and the United States, although they may sit back and enjoy using Kim Jong-un as a pit bull that keeps the United States and its Asian allies in a diplo-dither. Shared nuclear planning or exercises with North Korea are not precluded for Russia or China, but neither are they necessary for their security.

The third aspect of proliferation has to do with the possibility of new nuclear weapons states emerging from the ranks of those feeling threatened by regional rivals and-or concerned about the reach of America’s nuclear umbrella. With no doubt, many in South Korea and in Japan look askance at China’s aspirations for nuclear superpower status, combined with China’s already imposing economic strength and improving conventional forces. South Korea and Japan must also be concerned about North Korea’s growing nuclear arsenal and ambitions. These and other US allies might reflect on the experience of Ukraine, which gave up its nuclear weapons after the demise of the Soviet Union and might now be second guessing that decision in view of later events. For advocates of nuclear arms control and-or disarmament, an uncomfortable trade-off exists here. To obviate an Asian or Middle East leap into nuclear weapons status, the United States must provide reassurance that its own nuclear forces are sufficient not only for its own protection, but also for extended deterrence that protects allies. That reassurance might require a qualitatively or quantitatively enhanced US strategic nuclear force posture that is at odds with arms control or disarmament objectives. In a perfect arms control world, the United States, China, and Russia could cap their strategic nuclear modernizations at New START levels or thereabouts (that is, 1,500 operationally deployed warheads on intercontinental or transoceanic launchers) with order-of-magnitude verification based on national technical means. There would still be space and cyber to deal with, but it does not seem impossible to set limits also on hardware that already provides for sufficiency and more in mass destruction, should deterrence fail.

Outlasting or outran? Biden’s nuclear legacy will be one of continuation of preexisting plans for US strategic nuclear modernization. But this trajectory has been increasingly called into question by political leaders and national security experts—and promises to remain as such in the years to come.

China’s nuclear modernization and the potential collaboration of China and Russia (and, to a lesser extent, North Korea) in military and security policy do require superior US and allied intelligence collection and assessment. However, nuclear strategizing demands more than force building. US nuclear forces support the United States’ grand strategy and foreign policy in the largest sense, but they are not a one-size-fits-all solution. The question of “how much is enough?” has no unique answer: It depends on the nature of the threat and the priority of nuclear deterrence compared to other missions. Capabilities for conventional deterrence and war fighting, for space domain mastery and control, and for cyber dominance are equally important.

Contrary to the pessimistic assumptions of some, arms control can play an important role here: It provides a means for understanding the strategic priorities of other powers, for exerting influence over their decisions about nuclear modernization, and for avoiding nuclear arms races or nuclear war based on misunderstandings and inadvertence. The next administration, whatever its color, must ensure that nuclear arms control is high on its foreign policy agenda.

Notes

[1] Treaty between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of State, April 8, 2010), http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/140035.pdf

[2] Xiaodon Liang, “Russia Links Nonstrategic Nuclear Exercises to Threats,” Arms Control Today, June 2024, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2024-06/news/russia-links-nonstrategic-nuclear-exercises-threats

[3] Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns and Mackenzie Knight, “United States Nuclear Weapons, 2024,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, May 7, 2024, https://thebulletin.org/premium/2024-05/united-states-nuclear-weapons-2024/

[4] For an expert assessment, see: Laurel Baker, “Interview: Rose Gottemoeller on the precarious future of arms control,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, July 29, 2024, https://thebulletin.org/2024/07/interview-rose-gottemoeller-on-the-precarious-future-of-arms-control/

[5] Nikolai N. Sokov, “The Battle of Kursk probably won’t result in nuclear weapons use against Ukraine. But Russian escalation vis-à-vis NATO can’t be ruled out.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, August 26, 2024, https://thebulletin.org/2024/08/the-battle-of-kursk-probably-wont-result-in-nuclear-weapons-use-against-ukraine-but-russian-escalation-vis-a-vis-nato-cant-be-ruled-out/

[6] Expert commentary appears in: Mark Galeotti, “Putin is moody and misfiring – and his regime is getting worried,” The Sunday Times (UK), August 18, 2024, in Johnson’s Russia List – #126 – August 20, 2024, [email protected]; and James Stavridis, “Ukraine’s Assault Inside Russia Is Putin’s Worst Nightmare,” Bloomberg, August 16, 2024, in Johnson’s Russia List – #173 – August 16, 2024, [email protected]. See also: Julian E. Barnes and Eric Schmitt, “Ukraine’s Incursion Into Russia Reveals a Dramatic Shift,” New York Times, August 15, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/15/us/politics/ukraine-incursion-russia-kursk.html

[7] Crisis stability or first strike stability means that neither side would derive a significant advantage from striking first in the last resort (preemption) or premeditated attack. Arms race stability means that one state’s deployed or proposed force components would not necessarily encourage another state’s offsetting countermeasures, including additional force deployments.

[8] See: Samuel Charap and Christian Curriden, U.S. Options for Post – New START Arm Control with Russia (Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND, July 2024), for pertinent discussion.

[9] Brad Roberts, et. al., China’s Emergence as a Second Nuclear Peer: Implications for U.S. Nuclear Deterrence Strategy (Livermore, Calif.: Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Spring 2023, p. 4, https://cgsr.llnl.gov/content/assets/docs/CGSR_Two_Peer_230314.pdf

[10] Madelyn Creedon and Jon Kyl, Co-Chairs, America’s Strategic Posture: The Final Report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States (Washington, D.C.: October, 2023), Executive Summary, viii, https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/America’s_Strategic_Posture_Auth_Ed.pdf

[11] U.S. Department of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, Annual Report to Congress, 2023 (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 2023), VIII, https://media.defense.gov/2023/Oct/19/2003323409/-1/-1/1/2023-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF

[12] Theresa Hitchens, “DOD ‘exploring’ options for nuclear buildup as part of strategic review,” Breaking Defense, August 1, 2024, https://breakingdefense.com/2024/08/dod-exploring-options-for-nuclear-buildup-as-part-of-strategic-review/, also in Johnson’s Russia List 2924 – #162 – August 2, 2024, [email protected]

[13] Ibid. See also: David E. Sanger, “Biden Approved Secret Nuclear Strategy Refocusing on Chinese Threat,” New York Times, August 20, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/20/us/politics/biden-nuclear-china-russia.html

[14] Henry Sokolski, “Xi and Putin Are Building More Nukes: How to Compete,” in Sokolski, ed., China, Russia, and the Coming Cool War (Arlington, Va.: Nonproliferation Policy Education Center, June 2024), p. 13, http://npolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/2402-China-Russia-Cool-War.pdf

[15] Lawrence J. Korb and Stephen J. Cimbala, “The Future of Missile Defense,” The National Interest, February 9, 2024, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/future-missile-defense-209252

[16] Vipin Narang, quoted in Sanger, “Biden Approved Secret Nuclear Strategy Refocusing on Chinese Threat.”

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.