Can they control the weather? How the secretive history of weather weapons fuels conspiracy theories

By Justin Key Canfil | November 22, 2024

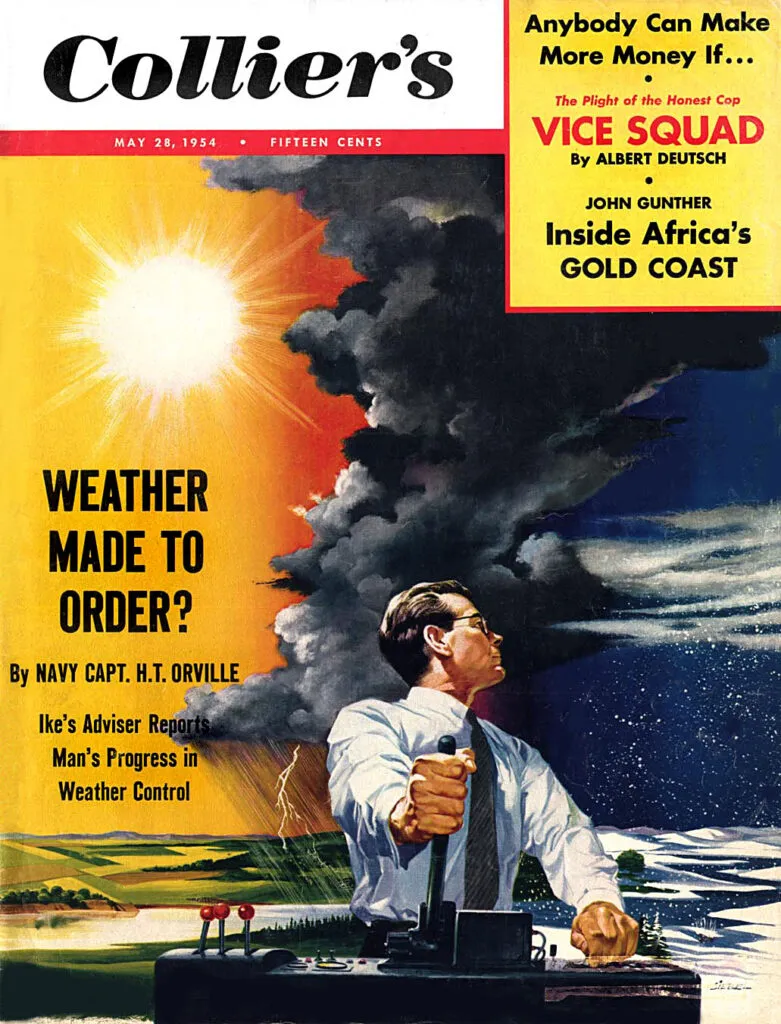

"Weather Made To Order?" Illustration by Frederick Siebel for Collier's magazine cover story in May 1954. (Photo: James Vaughan/Flickr)

"Weather Made To Order?" Illustration by Frederick Siebel for Collier's magazine cover story in May 1954. (Photo: James Vaughan/Flickr)

In the wake of the devastation caused by hurricanes Helene and Milton, online conspiracy theories about weather control have flourished. FEMA Administrator Deanne Criswell described the storm of disinformation as “absolutely the worst I have ever seen.” At the vanguard of conspiracy theories is Republican Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene (GA-14), who tweeted, “Yes they can control the weather” to her 1.2 million followers shortly before Hurricane Milton hit.

Rep. Greene’s post sparked questions and an immediate backlash, including from fellow Republicans. But the news cycle quickly picked up the story, prompting President Biden to issue a statement calling the claims “stupid” and “beyond ridiculous.” Undeterred, Greene has doubled down several more times. It may be tempting to dismiss these claims, given Rep. Greene’s track record of touting baseless and hateful conspiracy theories. But in this case, as with many conspiracy theories, there is a small kernel of truth to her vastly misleading claims about hurricane control.

Although it may sound like science fiction, the US government once engaged in serious research into weather weapons and other hostile environmental modification technologies. The US eventually halted its pursuit of weather weapons—not because using weather modification as a weapon was impossible, as is often assumed, but because of the possibility that such a terrifying technology was a “Pandora’s box” that might fall into the wrong hands.

Government interest in weather control is longstanding, dating from at least 1891. It reached its zenith in the early 1970s before being banned by the Environmental Modification Treaty, which forbade “widespread, long-lasting or severe” weather weapons for “hostile purposes.” Some 78 countries have joined since 1977. Many weather weapon program details remain shrouded in secrecy, but we now know more about how seriously top US officials regarded them at the time. In research now undergoing peer-review, I analyzed hundreds of pages of declassified documents from several US government archives. In contrast to the presumption that the treaty was a “face-saving” document designed to give the US political cover for Vietnam-era scandals, the internal record reveals that the superpowers were indeed engaged in serious research into strategic weather weapons—and terrified that the other side could get there first.

A number of weaponized concepts were explored over the years—artificial lightning, volcanoes, and earthquakes that could level enemy cities, and atmospheric modifications that could cause cancer or starve agricultural production, among other things. But most applied research has been directed at rainmaking and hurricane control. Post-war interest was piqued when the US Strategic Air Command proclaimed in 1954 “that the nation that controlled the weather would control the world.” (Readers may recognize a familiar line. In 2018, Vladimir Putin made the same prediction about artificial intelligence, telling a student group, “the one who becomes the leader in this sphere will be the ruler of the world.”) Just three months after Sputnik, a Presidential Science Advisory Committee report described weather control as the “next white hot fight” of the Cold War. In the months following, famous futurists such as Jon Von Neumann, Henry Houghton, and Herman Kahn also weighed in, believing that weather weapons would soon be within reach.

We now know of numerous weather modification experiments that took place between 1946 and 1983. When Hurricane King approached the Florida coast in October 1947, the United States initiated Project Cirrus, for which US aircraft dumped 130 pounds of crushed ice into the storm in an attempt to moderate windspeed. Soon afterward, the hurricane intensified and veered inland, hitting the city of Savannah. While it is now understood that the effect was due to natural steering currents, the Cirrus project lead, Nobel laureate Irving Langmuir, stoked conspiracy theories by publicly claiming credit. Hurricane victims threatened to sue in response, forcing the United States to continue hurricane control research in Project STORMFURY (1962-1983) “on the down low.”

During the Vietnam War, the United States later sought to apply what it had learned by launching Operation Popeye. Between 1967 and 1972, the Air Force conducted cloud seeding experiments over targets in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos to extend monsoon season, disrupting troop and supply movement on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. In one example, according to a memo to the president from then-National Security Advisor Walt Rostow, one of these experiments caused a landslide in Vietnam’s A Shau Valley, killing scores of enemy combatants. Popeye came under intense scrutiny between 1971-1974 when the Washington Post and New York Times published exposes. In an effort to shield the program, US officials downplayed, stonewalled, and repeatedly contradicted themselves in congressional testimony, heightening suspicion. US Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird had also assured Congress that no cloud-seeding was underway in Vietnam. Caught in a lie, he was forced to apologize, lending further credence to conspiracy theorists. By the time more details came to light in May 1974, there was popular momentum for a ban on weather weapons, a position the US government then favored.

Public pressure alone cannot explain the country’s willingness to abandon weather weapons. Campaigns to limit military technologies are most successful when policymakers discover that such technologies are either ineffective or replaceable. Rarely are promising new military technologies restricted in anticipation of their feasibility. As the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists can attest, technologies seen as useful, such as nuclear weapons, have survived intense criticism. Likewise, the Nixon White House, embattled over Popeye, initially sought a tenfold increase in funding for follow-on weather warfare experiments in Project Compatriot.

So what actually motivated the United States to push for a ban on weather weapons? As I show in my research, by 1974, US officials had come to fear that their enemies, especially the Soviet Union, might acquire the most dangerous kinds of environmental modification technologies first.

Even during the 1960s, the White House was optimistic about its innovation advantage in weather weapons. In 1971, Nixon’s team found that rainmaking techniques were “either in hand or in early prospect” and predicted a hurricane warfare capability by the end of the 1970s. By late 1972, however, the US intelligence community had come to believe that the Soviets had a probable edge. According to the CIA, the Soviet program was estimated to be six times larger. Soviet knowledge was “believed to be [at least] equal to our own” and they “do everything we do except hurricane modification”—an area in which they trail only “by 5 to 7 years.”

US decisionmakers faced a choice: multiply US spending in an already controversial and still poorly-understood technological arena in the uncertain hope of outpacing the Soviet threat or collude with the Soviets to make sure the most terrifying technological concepts did not become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Moreover, by taking the initiative, the United States could try to carve out exceptions for things it was already good at, thanks to Popeye—rainmaking and fog control. They opted for the latter. The Soviets, probably fearing the same, were amenable.

In different ways, the Environmental Modification Treaty was both far- and short-sighted. It was far-sighted in that it is a rare example in which states voluntarily agreed to shelve a promising military technology during the research stage, before its usefulness could be fully ascertained. However, it was also short-sighted in the sense that it was purposely designed not to constrain certain types of weather control research. In particular, the United States was careful to ensure nonaggressive or localized weather control research would not be banned. Continued research may be helping to feed conspiracy theories about the extent to which we can actually control the weather.

Disinformation campaigns are most successful when they can attach themselves to a kernel of truth. Moreover, weather is by definition a highly localized phenomenon. Research by Dan Silverman shows that disinformation is especially likely to take hold when audiences are spatially removed from events, which is the case for most people who receive hurricane news. And forthcoming research by Sabrina Arias and Chris Blair reveals that personal exposure to a hurricane tends to increase support for climate action, regardless of partisan identification or political ideology, at least in the immediate aftermath. This could also explain why Republican officials in the most-affected states—Florida and North Carolina—were among the loudest voices condemning Greene for her absurdly misleading tweets.

There are at least three other reasons why weather control disinformation might be so prevalent.

First, weather control is, in fact, to some extent possible. China made headlines for its large-scale efforts to reduce cloud cover prior to the Beijing Olympics. Saudi Arabia is using cloud-seeding to aid agriculture. Governments around the world are actively examining its usefulness at combatting the worst effects of climate change. However, the reality is that today’s weather control technology—arguably because of the constraints imposed by the Environmental Modification Treaty—is extremely primitive. But disinformation about “weather weapons” is harder to refute in a world where states exercise a modicum of weather control as opposed to none at all.

Also, many of the techniques states use to quell bad weather—namely, the spraying of water condensation nuclei, primarily silver- or lead iodide—could have offensive or defensive potential, depending on how they are employed. CIA and Air Force interest in tactical weather weapons has endured over the years, and some US force planners have even argued for resuming research on strategic weather weapons in the 21st century. But all known weather control programs since 1977 have had a peaceful orientation. Most if not all technologies have some dual-use implications, but when distrust and secrecy are high, and the consequences of being wrong would be severe, observers tend to assume the worst. Since this is complicated science—something the general public can easily confuse without good information and reporting—weather control is a target-rich environment for disinformation.

Third, matters are complicated by secrecy. Even in commercial, peacetime contexts, companies are incentivized to protect trade secrets and guard research activities, lest their competitors scoop them. This secrecy can inadvertently facilitate conspiracy theories, especially when governments are caught obfuscating. In 1952, for instance, a devastating flood hit the village of Lynmouth in Britain. Fifty years later, in 2001, declassified records revealed that the Royal Air Force (RAF) had been conducting cloud-seeding experiments in the vicinity just prior to the flood. Correlation is not causation, but the RAF’s insistence on secrecy—and in particular its insistence that no experiments had been conducted prior to 1955—has aroused new suspicions, despite no definitive evidence of a connection.

While countries are engaged in limited weather control activities, it is important not to overstate. Current technologies cannot cause hurricanes, but they might prove useful in mitigating some of the worst natural disasters to come. On the one hand, the general public has been told for decades that climate change is caused by human activity. On the other, they’re being told that human control of the weather is ludicrous. If the public is confused about the difference between weather (highly localized conditions) and climate (averages), disinformation peddlers can sow confusion and doubt about established science by framing these as politically motivated contradictions.

There is an emergent bipartisan consensus over the need to combat disinformation surrounding natural disasters, which scientists argue will only increase in prevalence and intensity as climate change worsens. Time will tell whether this emerging consensus persists in the incoming administration. During his first administration, President Trump was rumored to have floated a very different kind of hurricane control—that is, nuking a hurricane’s eye—which physical principles dictate would likely only add more energy to the storm. For conspiracy theorists, the Trump administration’s apparent willingness to pursue all options could present a litmus test when the next hurricane comes.

Moving forward, it is vital that policymakers increase public awareness about the limits, context, and actual potential of weather control technologies so that citizens can make informed decisions about how to manage the coming consequences of climate change—and who to trust when the next storm hits.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: ENMOD, climate change, cloud seeding, extreme weather, hurricanes, weather control, weather weapons

Topics: Climate Change

Yes we do know that humans have affected climate and weather with our massive carbon use. But as far as ‘controlling the weather, that is only going to happen if we can get world wide reduction of carbon fuels and emissions, to lessen our footprint on the planet and hope we return to normal weather patterns in decades ahead. And of course we can expect 4 more years of loudly proclaimed conspiracy theories, one of which claims that our scientists have repeatedly ‘weaponized’ the weather by choice. Senseless. Fact checking is now a way of life.

Mark, We won’t return to “normal” weather patterns. Not before thousand of years even if we’d stop 100% of our carbon emissions by tomorrow. Carbon is stable element and takes hundreds of years to dissipate. Climate we knew before industrial era is behind us. The carbon we already release in the atmosphere is well installed and will impact the global temperature as long it remains in the atmosphere. Imagine yourself filling a pool with water. If you stop filling the pool, the water will remain in the pool. It will evaporate of course but it’ll take very long time… We… Read more »

You forgot about HAARP, https://haarp.gi.alaska.edu/ which was the reason for the Environmental Modification Treaty.

after, helene, a friend posted a calculation that he contended proved that it was silly to think people could ever manipulate hurricanes. the amount of energy certainly is immense, but perhaps one doesnt have to contend with all of it, perhaps just a tipping point of some sort. at any rate, past governmental programs and decisions/lack of judgement, figure into people’s willingness to believe that those in control have base motives because in fact they have had. do they lie about it, always. it gives citizens cause to think, i wouldn’t put it past them, and they are right in… Read more »