Is the reign of tech titans coming to an end?

By Steven Feldstein | November 5, 2024

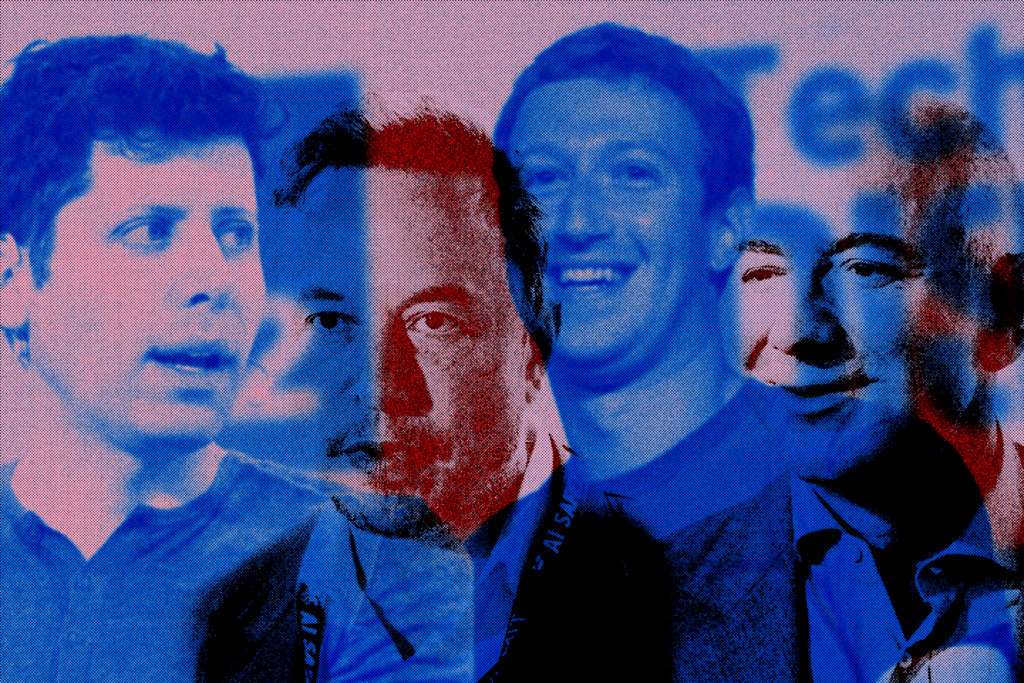

Have tech CEOs become so powerful that they are usurping the authority of the state and reshaping the global order? Illustration by Erik English; original photos by UK Government, TechCrunch, JD Lasica, Pleasanton, CA, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons, depositphotos.com

Have tech CEOs become so powerful that they are usurping the authority of the state and reshaping the global order? Illustration by Erik English; original photos by UK Government, TechCrunch, JD Lasica, Pleasanton, CA, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons, depositphotos.com

On October 25, The Washington Post dropped a bombshell on its readers, announcing that it would refrain from endorsing a presidential candidate in the upcoming election. Since 1976, when The Post backed Jimmy Carter, its editorial board had issued an endorsement for every presidential election. The news ignited a firestorm. Martin Baron, the former Post editor featured in the film “Spotlight” posted on X that the newspaper’s decision was “cowardice, with democracy as its casualty.” Famed Watergate reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein said this decision “ignores The Washington Post’s own overwhelming reportorial evidence on the treat Donald Trump poses to democracy.” It quickly emerged that The Washington Post’s billionaire tech owner, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, had personally decided to end the paper’s decades-long practice of endorsing presidential candidates. He became a special target of derision. Robert Kagan, who resigned from the paper’s editorial board following the announcement, characterized Bezos’ decision as “clearly a sign of pre-emptive favor currying with Trump.” Many were furious that a single individual could wield such power and muzzle one of America’s most prominent media outlets. But another narrative also took hold: Bezos’ decision to stop The Post’s endorsement indicated weakness. Bezos was so concerned about the consequences of publicly siding with Kamala Harris—in case Trump were to win reelection—that he preferred to use his power to suppress the paper’s voice than risk Trump’s ire. Bezos’ choice points to a larger question playing out today: Just how much power do tech titans wield?

Two dueling narratives are playing out regarding the power wielded by tech titans like Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, Sam Altman, Jensen Huang, and others. The first narrative goes like this: Tech CEOs have become so powerful that they are usurping the authority of the state and reshaping the global order. The immense scale of the companies they’ve founded—their gigantic capital reserves, captivating brands, and sophisticated technologies—have reinforced an aura of invincibility. With their vast resources, tech giants are uniquely shaping global outcomes—from determining how countries fight wars (such as in Ukraine) to deciding what heads of state can say online (world leaders who at one point were banned from Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, now X, include Donald Trump, Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro, Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, and Belarus’ Alexandr Lukashenko). As Ian Bremmer opined in a debated article in Foreign Affairs in 2021: “States have been the primary actors in global affairs for nearly 400 years. That is starting to change, as a handful of large technology companies rival them for geopolitical influence…Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Twitter are no longer merely large companies; they have taken control of aspects of society, the economy, and national security that were long the exclusive preserve of the state.” Or take Marina Koren’s September piece in The Atlantic, where she declared that “Musk is becoming an internet god” and that his combined control of space-based internet and social media has allowed him to wield “unprecedented power.”

Elon Musk’s heavy hand in the Ukraine war is an oft-cited example of the reversal of power between governments and companies. At the start of the conflict, Russian forces disabled Ukraine’s internet communications and threw its defense into disarray. In desperation, Ukrainian leaders pleaded with Musk to send them Starlink terminals. Musk assented, and days later Kyiv received 500 Starlink terminals with hundreds more to follow. Those terminals helped Ukraine mount a counterattack and to push Russian forces out of Kyiv. But then Musk started getting cold feet, worrying that Ukraine’s attacks could spur a nuclear war. Like other tech titans, Musk doesn’t have much experience in political or military affairs, yet his decisions have major geopolitical consequences. In this case, as Walter Isaacson recounts, Musk secretly chose to disable Starlink coverage off the Crimean coast due to fears about Russian escalation. His personal decision alone—which Ukrainian military officers found out about at the last minute—jeopardized a vital mission to attack Russia’s Black Sea fleet and forced Kyiv to scrap the operation.

But other commentators are more skeptical about the sway of tech titans. A second narrative maintains that the power of tech CEOs is waning—that geopolitics have compelled governments to reassert their authority over companies. In September, after Musk caved to Brazil’s Supreme Court and announced that X would remove accounts on the orders of a Brazilian justice, the New York Times wrote that “the moment showed how, in the yearslong power struggle between tech giants and nation-states, governments have been able to keep the upper hand.” Or in August, after France arrested Telegram founder Pavel Durov and indicted him on multiple charges, Will Oremus said in The Washington Post that tech CEOs “are facing the revenge of the regulators” and that this heralded the “end of an era…in which tech titans enjoyed free rein to shape the online world—and a presumption of immunity from real-world consequences.”

Which narrative is correct? Are tech titans more powerful than ever before and holding nation-states subservient to their whims? Or have commentators exaggerated the influence of tech moguls (when in fact governments are reasserting their authority over the industry)? As it turns out, neither argument fully captures the global reality. The power of tech titans is limited by several factors including whether they’re operating in a democracy or autocracy, and to what extent “techlash” has incentivized bureaucracies to claw back power from tech moguls. On the flipside, individuals like Altman or Musk, who are pioneering innovations in emerging sectors like space-based technologies and frontier AI, continue to exert outsized influence.

Tech titans face wildly different prospects in democratic countries versus authoritarian contexts. From the outset, autocratic leaders recognized the power inherent in digital networks and new technologies and sought to harness them accordingly. For China, this meant erecting a Great Fire Wall and banning Western platforms like Facebook and Google in the late 2000s. China made it plain to Musk and his contemporaries that there were strict limits to what the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) would tolerate. In an interview with the Financial Times, Musk acknowledged as much, revealing that Beijing “made clear its disapproval” of his rollout of Starlink in Ukraine and that it sought assurances that Musk “would not sell Starlink in China.” (Reporting also reveals that Vladimir Putin pressured Musk not to activate Starlink services over Taiwan “as a favor to Chinese leader Xi Jinping.”) At times, the Chinese Communist Party has weighed in publicly when it perceives that Musk has overstepped. Last year, after he tweeted about a US government report pinpointing a Wuhan lab as the origins of the Covid pandemic, the state-controlled Global Times warned Musk that he could be “breaking the pot of China” (akin to the adage “don’t bite the hand that feeds you”). Given the billions in subsidies and cheap land China has bestowed upon Tesla, that was hardly an empty threat.

Chinese party-state officials have also made sure that home-grown tech titans play by their rules. The fall from grace of Jack Ma, founder of e-commerce site Alibaba and Ant Group, is illustrative. Once known as “China’s most outspoken billionaire,” he suddenly went silent in 2020. He disappeared out of public view for months—no longer visiting the business school he founded, canceling a planned appearance on a TV show, and withdrawing from conferences. His transgression? In 2019, Ma delivered a speech in Shanghai to a group of senior officials. In his remarks, Ma challenged China’s regulators arguing that the country’s “financial system must be reformed,” and that state officials were impeding the financial technology sector with their “pawnshop mentality.” Within a week, the Chinese Communist Party torpedoed Ant Group’s long-planned $37 billion IPO, and Ma went into seclusion. The broader message was clear: Challenge the state and suffer the consequences.

Other authoritarian countries, as well as weak democratic states—such as Russia, Iran, India, and Türkiye—have also successfully opposed tech moguls. They have imposed draconian penalties against Big Tech’s products and dared companies to defy them. In Russia, Putin is building a “sovereign internet” and severing ties with most Western platforms (only YouTube remains standing in the country and its operations are increasingly imperiled). In India, the government has used coercion to intimidate tech companies, threatening to arrest employees that don’t comply with its rules. Last year, The Washington Post disclosed that politicians from the ruling party were “abetting violence and fanning incendiary speech” on Facebook to stoke their base. Despite repeated warnings, Zuckerberg delayed taking action for fear of “antagonizing” Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Even in full-fledged democracies, there is a growing “techlash” against the power wielded by tech moguls. Gideon Rachman makes a compelling argument that democratic governments retain a key authority that eludes Musk and his cohorts—“the ability to make and enforce the law.” Unquestionably, Western democracies have shown a lag between their capacity to regulate Big Tech and their willingness to do so. Slowly, however, democracies are reversing course. Europe is a good case in point. In recent years, the European Union has expanded its regulatory push, cracking down on social media under the Digital Services Act, taking aim at Big Tech’s monopolistic practices under the Digital Markets Act, and even taking a swing at setting AI policy with legislation in 2024. The United States, at least under Biden’s tenure, also got into the act. Lina Khan’s forceful stewardship of the Federal Trade Commission combined with Jonathan Kanter’s anti-trust push at the Justice Department resulted in several landmark cases that have trimmed the sails of large technology companies (just in August, a federal judge declared Google’s search engine to be an illegal monopoly, setting up the Department of Justice to consider requesting a breakup of the company). While this may not represent the end of the “digital gilded age,” Silicon Valley’s boom times have hit a rocky patch.

Despite these setbacks, the power of today’s tech titans remains strong. In emerging arenas like AI, space and satellite technology, and quantum—where governments are dependent on private companies to drive innovation—tech moguls dominate the agenda. Altman, for example, who weathered a hiccup earlier this year when OpenAI’s board tried to depose him, has come roaring back. He now seeks as much as $7 trillion to “reshape the semiconductor industry”—a figure that that would dwarf the GDP of every country in the world save the United States and China. Or take Jensen Huang, the founder of Nvidia, one of the highest capitalized firms on the planet. He recently concluded a “rock star” visit to Taiwan, where clad in his “signature black leather jacket,” he spoke to throngs of adoring fans at a packed stadium in Taipei (and even threw out the first pitch at a baseball game for good measure). As for Musk, his rockets “effectively dictates NASA’s rocket launch schedule.” The Pentagon relies on SpaceX to get most of its satellites into orbit. In 2023 alone, his companies received close to 100 different contracts with 17 federal agencies worth $3 billion.

Yet the reign of the current class of influential tech titans is likely to be short-lived for two reasons. The first has to do with the arc of innovation. Technology is defined by diffusion. Breakthrough inventions disseminate quickly in the world. New ideas do not stay bottled up in a laboratory or confined to a particular geography. Rather, they spread like wildfire. Innovations are copied, imitated, and reverse-engineered until the rest of the world catches up. In the twentieth century, industrial labs such as IBM Research, Bell Labs, and Xerox PARC dazzled the world with their breakthroughs. For a variety of reasons—shifting corporate priorities, stagnancy, and the dispersion of younger, hungrier researchers to other places—they became footnotes in history, eclipsed by Google, Nvidia, SpaceX, OpenAI, and others. Someday, these newer stand-ins will in turn be supplanted by more ambitious rivals. At its core, that is the story of Silicon Valley.

Second, there is a natural limit to how much power tech moguls can amass before states cut them down to size. As Jack Ma and Pavel Durov have already learned, governments do not take kindly to outsider challenges (in the case of Durov, years of flouting law enforcement requests finally came home to roost on the tarmac of Le Bourget Airport). Bureaucracies and lawmakers are fighting to reclaim their authority. In authoritarian states like China, officials are applying coercive means to rein in corporate leaders. Democracies in turn are using their regulatory powers to hold tech titans in check. While tech CEOs appear formidable today, the future is murkier. Scholar Moisés Naím has spent years analyzing the exercise of global power. In his book, The Revenge of Power, he considers the present dominance of tech leaders and writes that “such power is unlikely to last in its current and extreme form, as governments are beginning to try to rein in the giant technology companies.” Naim points out that while this tug-and-pull “will be with us for decades,” it is also “safe to expect that the unbridled power enjoyed by big tech companies since their inception will be more constrained in the future.”

So where does this leave things? Tech titans will resist relinquishing the reins of power. In September, Zuckerberg spoke at Meta’s annual developer conference wearing a t-shirt that read, “Aut Zuck aut nihil,” a play on the Latin phrase “aut Caeasar aut nihil,” which means “either a Caesar or nothing.” When Caesar uttered the phrase, he was struggling for power in the Roman Republic and wanted to make clear that he saw no middle ground: he would risk it all to rule. Zuckerberg’s appropriation of Caesar’s phrase evokes a similar mindset: Today’s tech titans believe they are wholly responsible for leading their companies to glory. They will do everything in their power to maintain their supremacy. But constraints from Europe and US regulators, coercive pressure from China, Russia, and India, and the long arc of innovation belie an uncertain future. While today’s moguls continue to ride high, history tells us that their decline is likely forthcoming.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Elon Musk, Facebook, Google, OpenAI, apple, big tech, tech titans, the Washington post

Topics: Disruptive Technologies