How to inoculate yourself (and others) against viral misinformation

By Sara Goudarzi | February 24, 2025

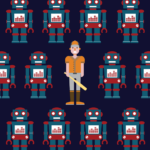

Exposing people to a weakened or inactivated strain of misinformation can help them build up cognitive resistance. (Bulletin illustration adapted from Suat Gürsözlü / Vadim Gannenko / depositphotos.com)

Exposing people to a weakened or inactivated strain of misinformation can help them build up cognitive resistance. (Bulletin illustration adapted from Suat Gürsözlü / Vadim Gannenko / depositphotos.com)

In 2020, as COVID-19 began to spread around the globe, theories surrounding the pandemic also started to circulate. One such supposition—as absurd as it might seem—was the idea that there was a correlation between 5G cellular telephone towers and the increased number of infections. This utterly false idea began to trend on social media and spread through messaging apps. Thousands, including celebrities and politicians, circulated this complete falsehood, leading to the burning of dozens of wireless communication towers in Europe. Although misinformation isn’t new, the rate with which it spreads is unprecedented, much as biological pathogens now travel much more quickly than in the past via today’s high-speed transportation systems.

But what if there was a way to protect people against misinformation viruses? Sander van der Linden, professor of social psychology at the University of Cambridge and director of the Cambridge Social Decision-Making Lab, wrote the book FOOLPROOF: Why Misinformation Infects Our Minds and How to Build Immunity; in it, he explains that there are ways to build immunity against falsehoods, much as vaccines that protect against pathogens.

I chatted with van der Linden about misinformation in today’s environment and how people can better protect themselves from falling for falsehoods.

The resulting discussion has been edited for length and clarity.

Sara Goudarzi: The terms misinformation and disinformation get thrown around a lot, could you explain what they mean and the difference between the two, at least for the purposes of your research?

Sander van der Linden: The short answer is that misinformation is generally defined as information that’s either false or misleading, and disinformation is misinformation but coupled with intention to deliberately deceive or harm people. Propaganda is disinformation with a political or corporate agenda.

How do you know something is intentional? Some of that is based on legal jurisprudence. For example, the courts have ruled that the tobacco industry—based on internal documents which show they intentionally created campaigns to deceive people—lied to the public for decades about the health risks of smoking. So that’s a clear example of disinformation.

How do you know something is false? One avenue for verification is the legal system where forensic evidence is presented; there are juries and there’s a trial, and the standard of evidence has to be beyond reasonable doubt [for criminal matters]. There’s the scientific method, and we look at things like expert consensus, where scientists around the world independently converge on an answer, for example that humans are causing climate change, or that the Earth isn’t flat. Of course, nothing is ever 100 percent certain, but we know, based on the best available evidence and the weight of evidence at any given point in time what we think is approximating truth. In addition to science, there are also professional fact checkers and there’s investigative journalism; so we actually have very good and varied means of establishing what is likely to be true or not.

There’s 2,000 years of philosophy about fallacious rhetoric, logical fallacies, manipulation, and snake oil salesman tactics that Aristotle and Plato wrote about. That hasn’t changed. People use the same dirty tricks to deceive people—impersonation, conspiratorial reasoning, appealing to emotions instead of evidence. We know that something is misleading when you falsely present opinions as fact, or you leave out important context in a news story. That’s quite an important distinction. Some people think of misinformation as stuff that is absolutely false, but the stuff that’s utterly false—like flat Earth and Jewish space lasers—is relatively small in terms of the proportion of people’s media diet. But if you look at misleading content—hyper-partisan, slanted, biased, and manipulative news—that’s much more prevalent.

So how big of a problem misinformation is depends on your definition. That’s why, when I chaired a consensus report for the American Psychological Association (APA), we decided to be inclusive, and define misinformation as both false and misleading information. For example, there was a headline from the Chicago Tribune, which is otherwise a credible outlet, that said, “A ‘healthy’ doctor died two weeks after getting a COVID-19 vaccine; CDC is investigating why.” The framing here falsely implied that the doctor died because of the COVID vaccine. It’s a correlation causation fallacy but also missing context. The CDC investigates many potentially unrelated side effect claims, that’s not a news headline, so the framing of it was highly manipulative. And research showed the impact of headlines like these are 50 times greater on vaccine hesitancy than fact-checked misinformation. That’s why the misleading category is quite important.

Then people say, “Fact checkers are biased, and Meta has just gotten rid of their fact checker program, because supposedly all the fact checkers are biased liberals.” But when you look at the research, which is very clear, it shows that independent fact checkers highly correlate with one another. We’re talking about very strong correlations. But here’s the key part: they don’t only converge on the same answer independently, but ratings from fact checkers also highly correlate with claims from regular bipartisan crowds. That should reassure us that there is some kind of ground truth that everyone agrees on and that there is misinformation.

Goudarzi: You’ve likened misinformation to a virus that spreads and infects minds. Can you elaborate on this and the mechanism by which this takes place?

van der Linden: I want to be nuanced about this, but my initial thinking around this comes from the fact that we borrow models from epidemiology that are used to study the spread of viruses, such as the Susceptible-Infected-Recovered (SIR) model, a very basic epidemiological model: There are some people in the population who are susceptible, some already infected and some recovering. That’s used to try to understand population-level dynamics. It turns out you can apply the same models to the spread of information on social networks. There’s a patient zero, somebody on social media who heard something that’s false, and now they spread it to other people in their network. So, the other nodes in the network—friends and so on—become activated. They’re receiving the misinformation and spreading it to other people. The scientific question is: Can you model the spread of the diffusion of false information in a network in the same way that a virus diffuses in a community? It turns out yes, you can use those same models, and they’re tremendously useful for trying to understand information spread. You can even calculate the R-naught (R0), or the average number of people that will get infected. And the R-naught’s different for different social networks, but they’re all larger than zero, meaning there’s infodemic potential.

The idea is you can model, on average, how many other people will go on to become infected after exposure. That’s why I think this is a useful tool. Everyone is susceptible. Now, here comes the nuanced part. I’m not saying that people are all walking around, without any capabilities, just being passively infected by information. That’s not exactly true for a virus either. Some people are more resistant to viruses than other people, and some people are more susceptible to misinformation than other people, so baseline susceptibility differs in the population. So, you make the model a bit more complex, allowing for different base level susceptibility. In reality, things are also perhaps a bit more complicated, in that the SIR model is simple, because it assumes a one-and-done kind of situation so that you come in contact with misinformation and you’re infected. But with information, sometimes you need to get exposed multiple times to a story before you’re convinced and want to share it with other people. Does that invalidate the viral analogy? I don’t think so.

We can distinguish what’s called simple from complex contagions. It’s the same with a virus: Somebody sneezes on you, and you don’t get infected. Sometimes somebody needs to stand very close to you and sneeze and cough multiple times for you to become infected. It’s the same with information. Some information is more complex. You need to be exposed multiple times from trusted people in your network for you to get activated and spread it to other people—that’s what we call a threshold parameter. The threshold for different people in the population is different. One of the main criticisms of the SIR model is that it doesn’t consider community structure. It doesn’t consider that people cluster in society, that they go to the same parties and so on.

That’s true for information too, and we have echo chambers and filter bubbles—this concept of homophily, which is that birds of a feather flock together. So, like-minded people congregate. But you can make the models more complex by adding a spatial network element that allows you to understand how information diffuses in a more clustered fashion. Of course, you’re getting away a bit from the from the most simplistic viral analogy, but that’s what they’re doing with real viral models as well. Because, of course, reality is complex, and models are simple. We’re trying to do our best to understand how viruses spread, and it pretty much works the same way with information. The parallels are really strong.

Goudarzi: You’ve indicated that misinformation exploits shortcuts in how we see and process information. What shortcuts are these, and is that why people can be duped?

van der Linden: The brain relies on rules of thumb or heuristics when it has to make decisions, when there are too many things to consider. When we stress the brain out, like give people tasks to overload their working memory, they start to rely on simple rules of thumb, because you must manage the flow of information in some way. If there’s too much information coming at you, you have to simplify, and manipulators can take advantage of that.

One of these effects is illusory truth, which is the idea that people find repeated information, including repeated misinformation, more likely to be true than non-repeated misinformation. This is a very sticky kind of mechanism: The more you repeat a lie, the more people start to believe it’s true because of what we call fluency. The brain uses the speed with which it can process a unit of information as an indicator of having some sort of truth value. So, the more fluid information becomes, the more familiar it is, the faster you can process it, and the more likely you think it’s true.

We know that two plus two is four because we rehearse it a lot. Unfortunately, it works the same way with lies. The more you hear it, the faster you are at processing it, the easier it is for the brain to assume that there must be something to it. That’s a very robust effect that’s been demonstrated in up to 75 percent of people in any given sample, including children. To give you an example, when you ask people, “what is the skirt is that Scottish men wear?”, People will report at the beginning of the experiment that it’s a kilt. But then, if you keep saying “it’s a sari, and you must have been confused,” at the end of the experiment, even though they’ve said the correct answer, people are more likely to think that it’s called a sari than a kilt. That is the illusory truth effect, and it’s because people are not using their prior knowledge in a useful way when accessing information in the moment.

At first, we thought illusory truth would work only for plausible things, but it turns out it works for implausible things too, like the Earth is flat. Now it’s not the case that people walk out of an experiment thinking the Earth is flat, but they think it’s a little more likely than it was when they came into the experiment. What’s interesting to me with illusory truth is that anyone is susceptible to that, and it also leads people to think that sharing misinformation is less immoral over time. The more it’s repeated, the more normalized it becomes. Over time, people start to think maybe there’s something to it, maybe it’s not so bad to share this stuff on social media.

The other mechanism is confirmation bias, which is the tendency to be quicker to accept information that resonates with what we believe is true about the world. It’s hard for the brain to deal with information that conflicts with how we think the world works, because you have to stop and be like “wait, it doesn’t resonate at all with what I believe or what I think is true.” So, people tend to not engage in that as much as information that already confirms what they want to be true about the world. A lot of misinformation is framed to feed into people’s social-political biases, because they know that people are quicker to accept them than to reject them.

When it comes to fighting misinformation, it’s such a big problem because there’s a continued influence effect. The continued influence of misinformation is that people will continue to retrieve misinformation from memory even when they’ve acknowledged a fact check. Fact checks are good and help reduce misinformation, but they don’t eliminate it in the brain. That’s because memory is like a network. There are links and nodes, and when you hear misinformation, you integrate it. Lots of links are made. When you try to undo misinformation in the brain, you might be able to deactivate a couple of links, but tons of others remain. It’s like a game of Whac-A-Mole.

A typical experiment that illustrates this puts people in the fMRI scanner and gives them a scenario that there was a fire in a warehouse, and there were oil and gas cans that caused the fire. Five minutes later, you read a report from the fire chief that says, “actually, the oil and the gas cans weren’t the cause of the fire.” But at the end of the experiment, when you ask people to make inferences, “why was there so much smoke?” people say, “because of the oil and the gas cans.” It’s a retrieval error. You can’t unring a bell. Often you can’t just undo it. That’s how we arrived at this whole idea of pre-bunking and inoculation and trying to prevent people from encoding misinformation in the first place.

Goudarzi: Is this tied to how misinformation modifies memories?

van der Linden: If you keep repeating something, you can distort people’s memories of past events. For example, they’ve done this with Brexit and other hot button topics; you give people a false statement and then you ask later if they had a memory of that event. They will say, “oh yeah, I remember that” even though it never happened. That’s probably because people want it to be true—it’s illusory truth—and they’ve been repeatedly exposed to it. The point of those studies was to show that with misinformation campaigns, it’s possible to distort people’s memory of what actually took place. You see that to some extent, with, for example, the war in Iraq. There have been some studies that show that many present-day Americans believe there were weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, even though that wasn’t true, because the media kept printing those headlines. These were suggestive headlines, and later there were corrections, but it continues to influence people’s memories and reasoning.

Goudarzi: What’s the mechanism of pre-bunking or inoculating people against misinformation?

van der Linden: The mechanism is very similar to an actual vaccine. The whole idea was that, if misinformation acts and spreads like a virus, maybe we can vaccinate people against it. So, rather than just giving people facts broadly, which is more kind of akin to a healthy diet or vitamin pills, you expose them to a weakened or inactivated strain of the misinformation, or the techniques that are used to produce misinformation, and you refute and deconstruct them in advance, so people can build up cognitive resistance.

Just as the body needs lots of examples to distinguish between invader and healthy cells, it’s the same with the brain. The brain benefits from lots of microdose examples of what manipulation looks like so that it can better differentiate and discern between the two when it’s “under attack.”

Most people don’t have the right cognitive antibodies to resist propaganda attacks in the moment. Sure, education is useful, fact checking is useful, but it’s so broad that when people are under attack in the moment, they don’t have the right mental defenses. That’s where inoculation is particularly useful. An example I once gave at a misinformation conference was to ask people why the Earth isn’t flat and who would be brave enough to stand up and explain the physical mechanisms. Even though we all intuitively know that the Earth isn’t flat, there was no one who had the right mental defenses to counter argue the point. Most physicists would have that knowledge accessible and could easily deconstruct it, but most regular people can’t. So, what you want to do is expose people to a weakened dose of an attack, and then actually give them the ammunition they need to deconstruct the fallacy and counter argue with the facts. Forewarned is forearmed, and that’s the idea behind inoculation.

Goudarzi: Inoculating, then, is different than providing people with critical thinking skills?

van der Linden: Critical thinking is, of course, a good thing and helpful, but it’s different from inoculation. If I’m going to bombard someone with conspiracy theories, critical thinking is a little helpful, but it’s not going to make them immune to conspiracy theories, because they don’t know how to use broad skills like that in a specific moment against a specific attack. It’s also not that useful to inject people with a vaccine against a highly specific conspiracy theory, because it doesn’t necessarily transfer to other conspiracy theories. So, I think what we try to do is sit somewhere in the middle between highly narrow specific vaccines, which we have developed when some story is coming that’s false that could be highly damaging during an election or a public health crisis, and that extremely broad critical thinking that people might not be accessing and recruiting in a specific enough manner.

From critical thinking, you might deduce that there seems to be something fallacious about this. But in the inoculation training, you’re exposed to the building blocks of conspiratorial thinking. We show people you can construct conspiracy theories using the same building blocks, its DNA.

It’s always some nefarious story of evil elites plotting behind the scenes. It’s also a fundamental attribution error or reinterpreting randomness into a causal event; 5G is a popular example. Why are there more coronavirus deaths near 5G towers? Of course, it’s because of population density, where there’s more towers, there’s more people living and more coronavirus deaths. But you could also create that into an interesting story, that the towers are somehow causing the deaths. In experiments, people come up with the most wonderfully elaborate conspiracy theories using those same building blocks, and then they start to compare them against real ones. After 10 minutes in the simulator, people start to realize, wait, conspiracy theories like Tupac Shakur is still alive, or Avril Lavigne is a clone, all follow the same pattern. They use the same tricks over and over again. So, if you bombard people with the whole range, you see that they’re becoming relatively immune, because they can identify and dismantle the core building blocks.

Goudarzi: How can you implement this tool society wide?

van der Linden: Initially, after lots of lab research and field tests, we moved to implementation. During the pandemic, we had a five-minute version of one of our games called GO VIRAL!, which was implemented by the World Health Organization (WHO). This was one of the largest public health campaigns we did at the time. The WHO, together with the UK government and the United Nations, scaled it and we were able to reach about 200 million people with that campaign.

Then we did another during the 2016 presidential election with Christopher Krebs’ team, who was the Director of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency at the time and was fired by Trump because he kept debunking Trump’s claims about election fraud. But they still implemented our game, which was about helping Americans spot foreign interference in elections and break down that playbook. We did that together with Homeland Security.

Then we started working with social media companies like Google, and we designed very short pre-bunking videos and thought what if we put them in the ad spaces on YouTube, and people can’t skip it? We could potentially reach billions of people all at once that way. Google tested it with a real campaign on YouTube and it was successful in helping people recognize manipulation.

Unfortunately, in the current environment, YouTube has not agreed to adopt this as a policy, and all the other social media companies have been worried and scared about the current administration and political pressure.

Some ask “why do you work with Meta? Why do you work with Google?” Well, they partly control the flow of information. So, if they want to implement evidence-based solutions, we should try to help them do that. But then the other side of the coin is that as soon as the incentives change, they’re no longer doing what’s in the public interest. Whether it’s a government or a social media company, they can do tremendous things to scale these things. But at the end of the day, they’re just not reliable long-term actors in terms of implementing solutions.

So, we’re going to schools and thinking of how we can implement this in education, from a very early age, so when students graduate, they’re empowered citizens who are more immune to manipulation and malinformation and disinformation.

Goudarzi: Those are all my questions. Is there anything that you’d like to add?

van der Linden: Given the current polarized environment in which we find ourselves, what we’ve tried to do is move away from specific claims and say “whichever side you’re on there’s these broader techniques that manipulators use: polarization, using fear, negative emotions, and conspiracy theories, and trolling and impersonating doctors and politicians.” It’s easier for partisans to agree that those are all bad things. Maybe focusing on that secondary, underlying manipulation tactic has a higher chance of getting bipartisan support than talking about specific claims, because there’s so much disagreement now and people are losing trust in fact checkers and science.

Goudarzi: I actually do have one more question that came to mind: Once you teach this technique to a person, can they transfer it to somebody else?

van der Linden: That’s a great question. One of the ways in which this deviates from the biological analogy in a positive way is that you can’t transfer a biological vaccine, you can’t just take a vaccine out of your body and give it to somebody else. But you can do that with the psychological vaccine. It’s kind of like the telephone game where the gist is still there, but it gets watered down in in every chain. The effect is lower, but there is this positive spillover. By doing that, you’re also accessing and rehearsing the material yourself, and the inoculation becomes stronger for people internally when they do that.

There’s a funny example of the people who made our videos, the graphic designers and the artists. After like six months of working on this project, they said every time they were listening to a politician on the radio, they would play this game where they would call out the manipulation technique. That’s this kind of vicarious sort of inoculation that happens that makes the prospect of herd immunity a little more realistic with a psychological vaccine.

The other thing I should add is that the big limitation of psychological inoculation is that it does decay over time. Just as with real vaccines, you need to boost people. You do have to reengage people, because people forget, and they lose motivation. The question is, how many times do you need to be boosted to have life long immunity? That’s the big question.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Disinformation, covid, misinformation, politics, propaganda, vaccines

Topics: Disruptive Technologies

No comments yet, at least a day after publication I can’t believe it! This is a top piece of information, exploring in detail one of the most important issues we face today and nobody has anything to say, to agree or disagree. He is not saying it’s all true. He is speculating but he is giving us plenty to think about, stuff we need to process. He has got me thinking about other virus-like contagions, such as a nation’s decision to go to war. Assuming this decision starts at a single point, in one person’s head, does the decision spread… Read more »

After extensive research into a little-known “conspiracy theory” about early nuclear history, I have found most of the statements in this article apply equally well to “established facts” from history that were misleading at the time but have become embedded in the culture. Even the experts resist the documented facts, preferring their “well-established” opinions over documentation that contradicts what they already believe. One historian I consulted actually acknowledged that he knew too much about the subject to be open to any new information. Sad, because a nation is the orphan of the history it doesn’t know, and — as we… Read more »

This is an excellent and insightful article! I particularly appreciate the focus on the psychological mechanisms behind misinformation, such as illusory truth and confirmation bias. The explanation of pre-bunking and inoculation as a strategy, akin to a psychological vaccine, is compelling. I found the discussion about the normalization of deviance, as described by Diane Vaughan in the context of the Challenger disaster, to be highly relevant here. [Diane Vaughan, The Challenger Launch Decision: Risky Technology, Culture, and Deviance at NASA]. The repeated exposure to and acceptance of misinformation, even when known to be false, mirrors the gradual erosion of safety… Read more »