Cara Despain’s multimedia installation Test of Faith features uranium glassware and manipulated projections of nuclear test footage. It debuted at the Bass Museum in Miami in 2022, and appeared in 2023 at the Orlando Museum of Art and the New Mexico State University Art Museum in Las Cruces.

Cara Despain’s 2022 installation Test of Faith, which combines uranium glassware with altered footage of nuclear tests, is an example of new art confronting the fraught legacies of the nuclear age. Cara Despain

Along a quiet, tree-lined street in exurban Middletown, Pennsylvania, a middle-aged woman and two children walk their small dog. Just beyond the neighborhood loom two massive concrete hyperboloid cooling towers. It is June 20, 1979, hardly three months after the partial meltdown at the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station, the worst nuclear plant accident in US history.

It is a dissonant American moment—with domestic dreams and nightmares occupying the same physical space—captured by photographer Robert Del Tredici. The image can be read literally: The American idyll runs straight through a nuclear disaster.

Three Mile Island’s cooling towers are visible in the background of “Yellow Brick Road,” a June 20, 1979 photograph by Robert Del Tredici, cofounder of the Atomic Photographers Guild. Robert Del Tredici, by permission.

Despite well-documented histories of nuclear disaster like Three Mile Island, we are today witnessing a renewed push for atomic energy to power artificial intelligence, the return of uranium mining in the American Southwest, and the appointment of an openly cavalier US Secretary of Defense who, though not technically part of the nuclear chain of command, will certainly be advising the President on existential matters concerning Russia, China, and Iran. As these and other causes of 21st-century nuclear anxiety emerge, artists are exploring new ways to comprehend and express the persistent links between technology, culture, and injustice.

When, at the apex of the Cold War in 1987, Del Tredici and photographers Carole Gallagher and Harris Fogel co-founded the international Atomic Photographers Guild, they were “dedicated to making visible all facets of the nuclear age.” Easily reproducible and distributable, photography proved an ideal medium for broadcasting the far-reaching and intricate political, environmental, and public health crises of the atomic age. The organization has amassed an archive representing seven decades of works by more than forty photographers documenting nuclear weapons development and testing; uranium mining and milling; atomic power and its handful of high-profile failures; nuclear waste and irradiated landscapes; and the people living “downwind” from these industries.

The Guild’s collection includes some of the earliest images of the nuclear era: Japanese photojournalist Yoshito Matsushige’s unflinching firsthand images of the aftermath of the Hiroshima bombing, whose horror is unambiguous, as well as Manhattan Project photographer Berlyn Brixner’s surreal documentation of the Trinity Test—otherworldly stills of the world’s first atomic explosion, captured at 10,000 frames per second.

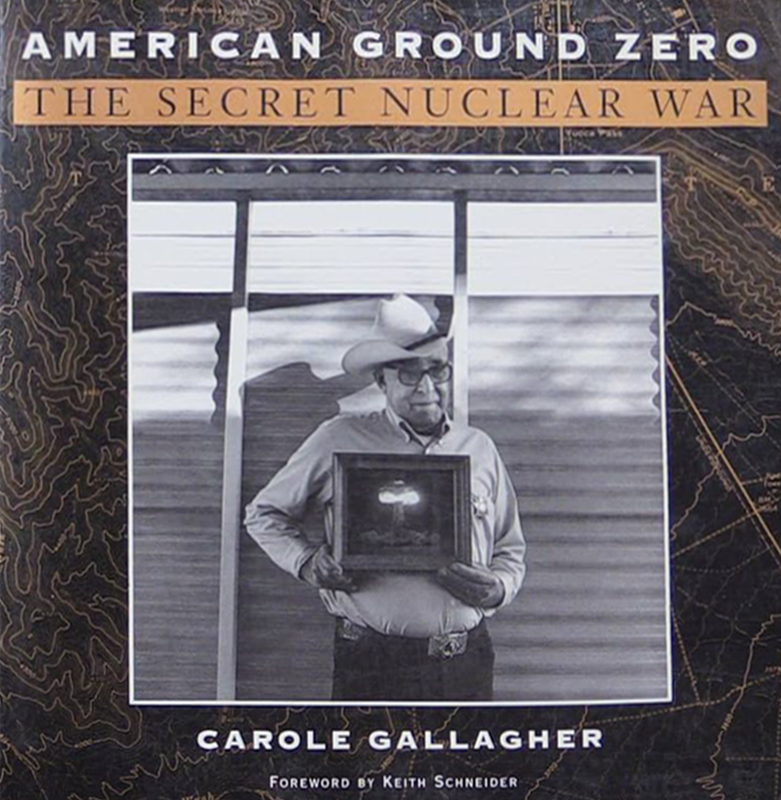

In 1993, after a decade of living and working in Southwestern Utah, Carole Gallagher published American Ground Zero: The Secret Nuclear War, a groundbreaking collection of candid interviews with and arresting portraits of Utah downwinders, Nevada Test Site workers, and “atomic veterans” dying of radiation-induced cancers. “In the following pages,” Gallagher wrote in the book’s prologue, “you will hear the voices of people long silenced, and by their portraits, icons of the atomic age, you may understand that their tragedy is universal.”

Other nuclear dangers have been experienced and documented less directly. A 1991 study by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) identified more than 45,000 sites contaminated or potentially contaminated by radioactivity across the United States alone. This dizzying figure points to the complex spatial and temporal legacy of all things nuclear. Because the half-lives of uranium, plutonium, and other radioactive byproducts of nuclear weapons and energy production are beyond human scales of time by orders of magnitude, humanity’s nuclear imprint is global and geologic in scale—so much so that, in 2015, an international group of scientists proposed that the planetwide persistence of radionuclides from atomic blasts mark the dawn of the Anthropocene epoch.

The confoundingly diffuse and omnipresent character of this nuclearized history and environment has made it a constant fixation for artists. Recent years have yielded notable expansions in what might be called transnational aesthetics of atomic critique, with the emergence of a new generation of artists who came of age after the conclusion of the Cold War. As demonstrated in the selections that follow below, these artists wrestle with extant legacies of uranium extraction and refinement, generational trauma, toxic landscapes, and the simmering collective paranoia that results from living under the threat of total annihilation for the better part of a century. Though influenced by the Atomic Photographers Guild, they are drawn more to non-literal or multi-layered depictions of nuclear injury and anxiety, incorporating multimedia sculpture, Indigenous totems, nuclear mascots, and taxidermized “super rats.”

Inspired by contradiction

The new generation of artists featured on this page draw on the Atomic Photographers Guild’s influence, but seem more inspired, aesthetically and formally, by the Guild’s least literal contributor, the late Patrick Nagatani. Born in Chicago just days after his family’s hometown of Hiroshima was destroyed by the Little Boy uranium bomb, Nagatani’s hallucinatory and often contradictory collage works layered photographs of Japanese tourists, US military sites, nuclear monuments, and Native Americans, illustrating the nuclearized world’s multitemporal and multilocational realities.

Patrick Nagatani, “Trinity Site, Jornada Del Muerto, New Mexico,” 1989

For forty years, Nagatani was faculty at the University of New Mexico, teaching thousands of students, including Diné experimental photographer and educator Will Wilson. Wilson’s own long-running, science-fiction-tinged photographic and installation series Auto Immune Response—wherein a Navajo man, played by Wilson, navigates stunning, but toxic post-apocalyptic landscapes—has been equally influential on younger artists.

Will Wilson, “Confluence of Three Generations,” 2015

As trust in institutions erodes, seemingly irreparably, and anthropogenic climate change reshapes everyday life across the globe, these 21st-century artists are embracing paradox, abstraction, and, occasionally, even play, as they stare down a future where nuclear states continue to proliferate weapons and lean into atomic power, despite no functional plans for dealing with colossal amounts of toxic waste, let alone an international nuclear conflict.

Cara Despain

Cara Despain’s installation, Test of Faith, seen here in 2023 at the Orlando Museum of Art. Cara Despain

Cara Despain

Hear Cara Despain describe her mothers’s hometown, which was hit by nuclear test fallout:

A big contingent of Utah downwinders were in Cedar City. It’s kind of your quintessential rural quaint Utah small town. Mostly sheep ranchers, Mormon settlers. But there's this other history that belies that.

On the morning of May 19, 1953, when the mother of interdisciplinary artist and filmmaker Cara Despain was eight years old and living in the largely Mormon community of Cedar City, Utah, the US military conducted a test (codenamed “Upshot-Knothole Harry”) of a 32-kiloton hollow-core implosion device atop a 300-foot tower on Yucca Flat at the Nevada Test Site. Poor calculations and changing winds resulted in a massive amount of nuclear fallout raining down onto southwestern Utah, earning the test the nickname “Dirty Harry.” Atmospheric nuclear testing continued on Yucca Flat for nearly another ten years. Over the next few decades, locals in Cedar City, St. George, and surrounding communities were diagnosed with lymphoma, melanoma, brain tumors, and cancers of the bone, breast, and thyroid, at rates several times higher than similar populations not directly downwind of the Nevada Test Site.

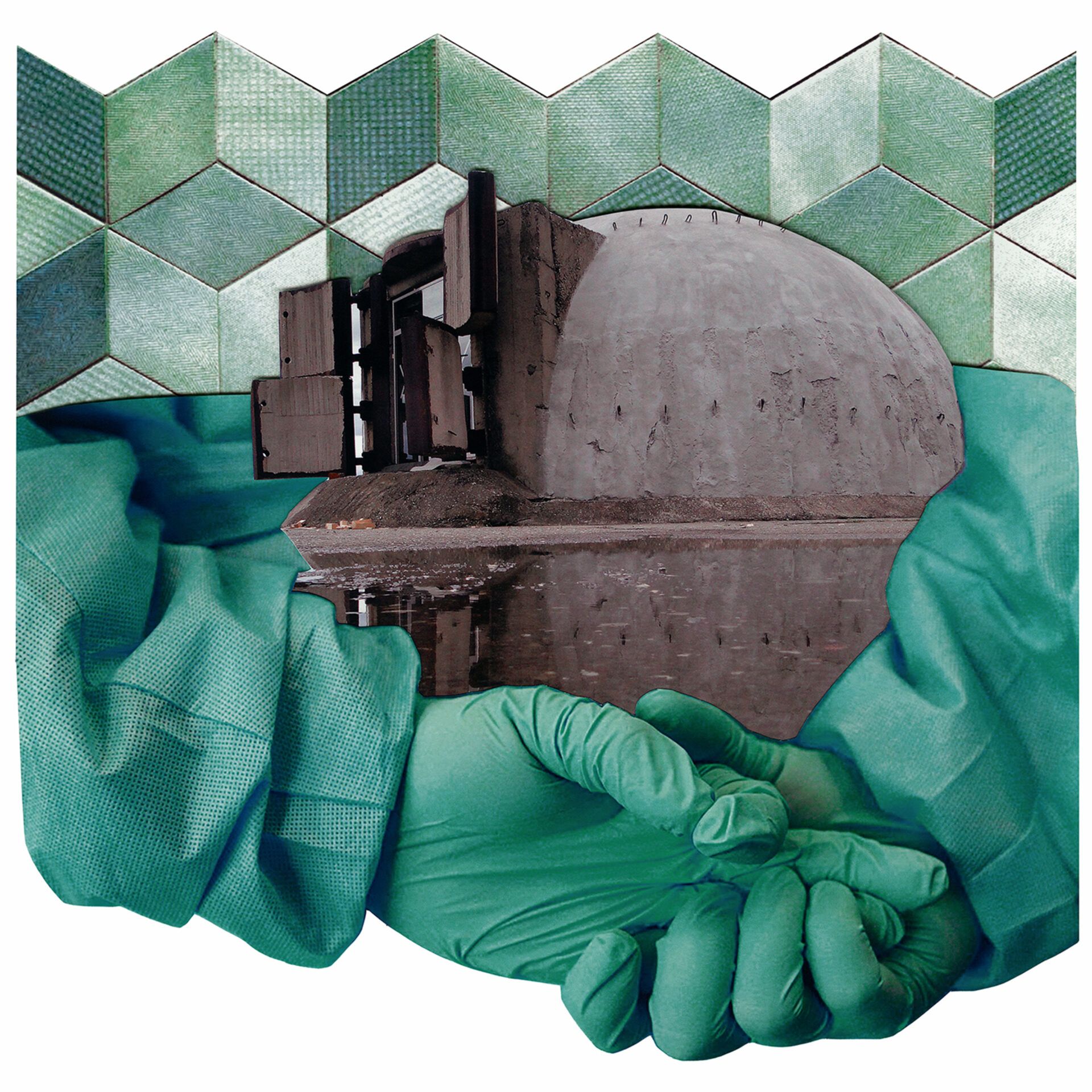

Despain spent most of her life in and around Salt Lake City before relocating to Miami, Florida, in 2010. Her immersive, multimedia installation Test of Faith (2022-23) incorporates the aesthetics of science-fiction to present a complex web of very real places and timelines that she describes as conveying “the latent psychic imprint and cultural memory left in the wake of weapons development and testing.”

Visitors enter through a viridescent archway—reminiscent of both the Palace of Oz and Stanley Kubrick’s obsessively symmetrical 2001 sets—embedded with Depression-era uranium glassware glowing under LED UV lighting. Inside, a three-channel video bathes the walls with declassified reels of atmospheric nuclear explosions at the Nevada Test Site. Despain mirrored the footage along its vertical center, resulting in hypnotic, demonic, Rorschach-like bursts that recall Isaac Asimov’s ultra-short story “Hell-fire,” wherein Satan’s visage emerges from a nuclear cloud. Piped in through surround-sound speakers is a layered recording of “Love One Another,” a Latter-day Saint hymn, nodding to Despain’s familial ties to Cedar City, one of several southwestern Utah towns where Mormons, eager to distance themselves from polygamy and to assimilate into American normalcy, branded themselves proud patriots. During atmospheric testing, the Atomic Energy Commission instrumentalized that patriotism to avoid accountability about fallout in southwestern Utah.

Joanna Keane Lopez

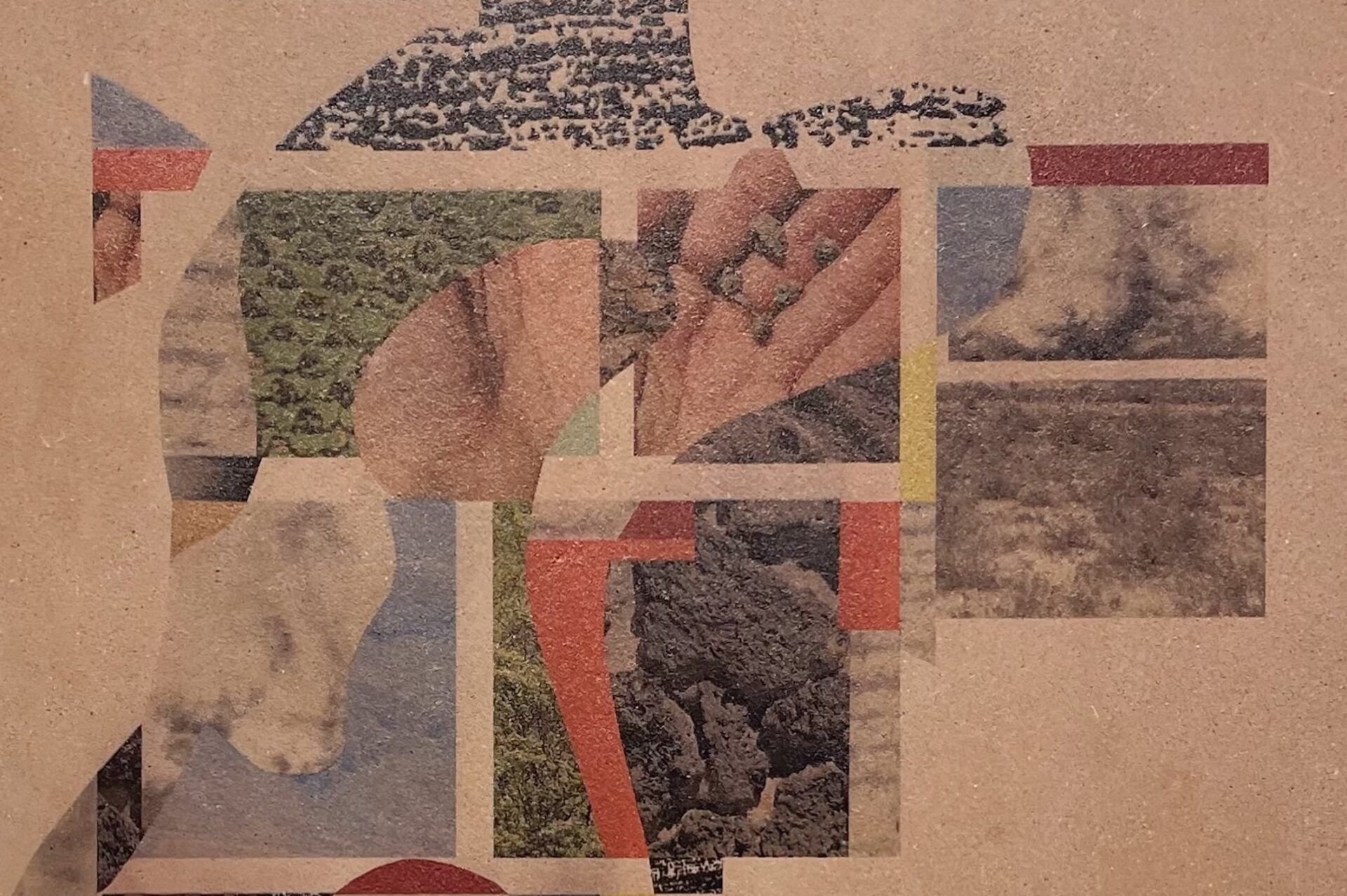

A detail of “Picking up Trinitite,” one of the mixed-media works in Joanna Keane Lopez’s recent series, Thrice Layered. Joanna Keane Lopez

Joanna Keane Lopez

Little did I know, at a young age, how intertwined my life would become with the testing, deployment, and detonation of radioactive bombs and uranium weapons.

— Damacio Lopez

(Joanna’s father)

Familial ties to irradiated landscapes also motivate Joanna Keane Lopez, an interdisciplinary artist born and raised in New Mexico. Keane Lopez’s father, the activist, academic, and depleted uranium expert Damacio Lopez, was two years-old the morning of July 16, 1945, when the world’s first atomic bomb, Trinity, nicknamed the “Gadget,” was exploded some thirty miles from his family’s home near Socorro, New Mexico. The region has since been subject to depleted uranium weapons testing by the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology. Keane Lopez’s mother, Colleen Keane, directed The River That Harms, a 1987 documentary detailing the catastrophic 1979 Church Rock uranium mill tailings spill on the Navajo Nation, which released more radioactive material than the Three Mile Island accident earlier that year but received comparatively little media coverage. Keane later spent a decade as a reporter for the Navajo Times.

Keane Lopez is an adobera and an enjarradora, having trained, respectively, in the traditions of earthen home-building and interior plasterwork. But with her family’s land potentially contaminated by both the Trinity test and New Mexico Tech, Keane Lopez’s ambivalence about constructing adobe homes with local materials has influenced her studio art practice. In May 2024 at the Stanford University Art Gallery, Keane Lopez presented Batter my heart, three-person’d God, a domestic-themed sculptural installation named after a John Donne poem, whose devotional stanzas reportedly inspired Manhattan Project director J Robert Oppenheimer’s naming of Trinity. In front of an organic brick wall sat a twin-sized bed, its simple but elegant frame fabricated from ponderosa pine. Triangular teeth, like stylized mountain peaks or gamma waves, jutted outward from its vertical slats. A colcha-embroidered quilt depicted Trinity fallout patterns, regional flora, and three figures: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. The work pointed to Trinity’s infiltration of domestic spaces, from fallout blanketing Damacio Lopez’s childhood home, to the bedroom at the forcibly vacated McDonald ranch house, where Oppenheimer’s team assembled the Gadget’s plutonium pit.

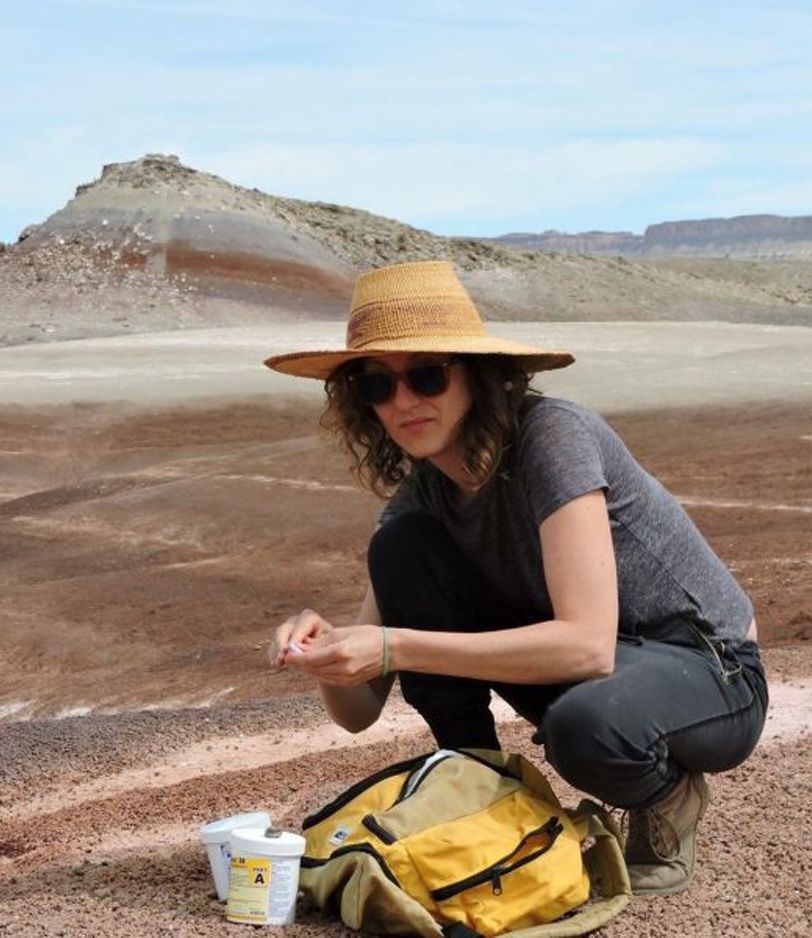

Recently, Keane Lopez debuted a new mixed media series, Thrice Layered, which uses adobe and acrylic pigments, maps, original photography, and drawing to represent overlapping histories of nuclear colonialism (the ongoing legacies of nuclear testing, uranium mining and radioactive waste dumping that disproportionately impact Indigenous or other vulnerable populations across the world). Here, Keane Lopez focuses again on central-southern New Mexico, emphasizing the historical, environmental, and political significance of the Trinity test on locals. The series is dedicated to the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium, a group of activists who have spent nearly two decades advocating for the expansion of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), which provides partial financial restitution—and, importantly, acknowledgement of harm—to specific populations of uranium miners, millers, and transporters, and communities downwind of the Nevada Test Site. Despite recent Senate approval to add Tularosa Basin downwinders and other groups to RECA’s scope, the program expired in June 2024 after stalling in the House of Representatives. The Department of Justice has since stopped processing claims.

Mallery Quetawki

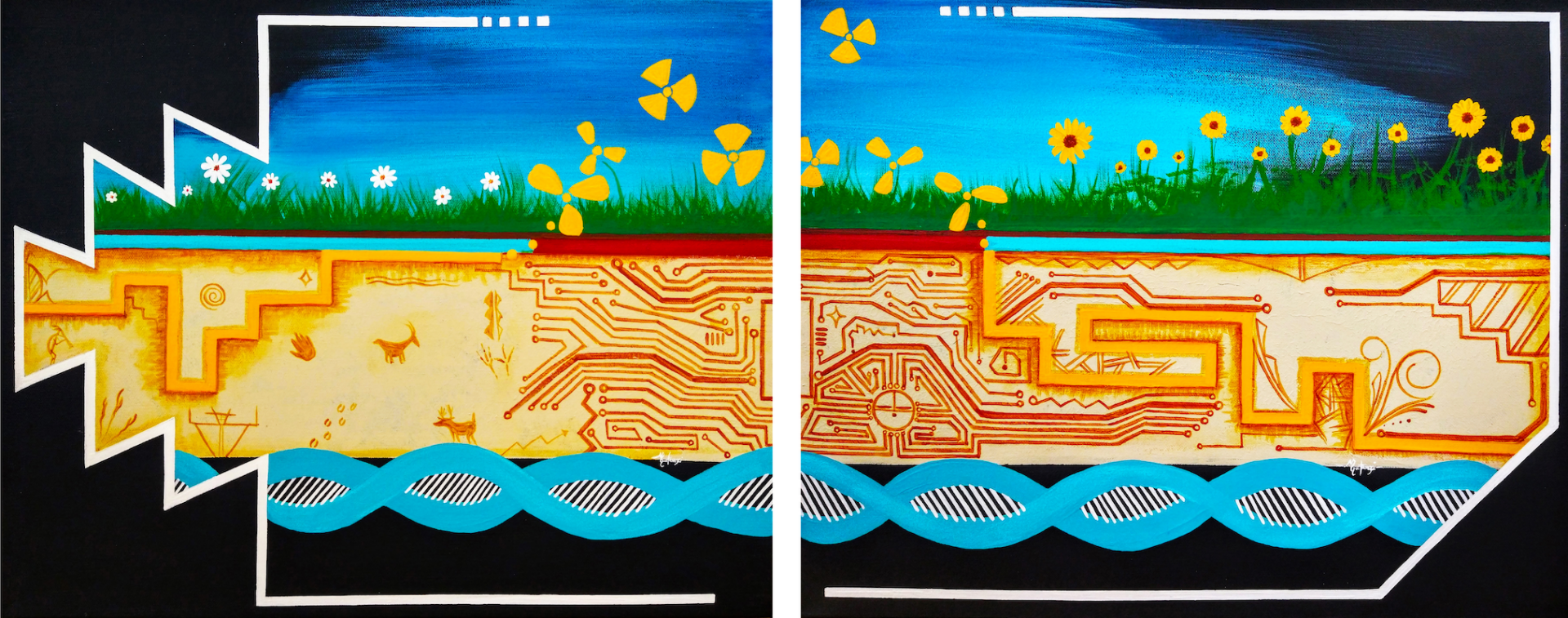

“Extraction & Remediation” (2020) represents decades of mining on Indigenous lands, from the start of extraction to current efforts to clean up contaminated sites. Mallery Quetawki

Mallery Quetawki in her studio/office in Albuquerque, NM. Marylene Mey for Southwest Contemporary

You see that the lifeline was disrupted, there was an opening, a gap that happened... and that's symbolizing extraction, specifically uranium.

According to the EPA, there are more than 500 abandoned uranium mines in what is today the Four Corners region of the Southwestern United States. The vast majority sit within the boundaries of the Navajo Nation, radically endangering public health for the Diné people and nearby Hopi and Pueblo communities. Following decades of exploitation, many Indigenous people have developed a deep (and self-preserving) skepticism towards institutions like the Energy Department and its claimed expertise. Of course, Indigenous ways of knowing are not necessarily incompatible with western science and medicine—or their attendant technologies—but such caustic histories of harm are not easily undone.

Enter artist Mallery Quetawki (Zuni Pueblo). In 2017, Quetawki was named artist-in-residence in the Community Environmental Health Program (CEHP) in the College of Pharmacy at the University of New Mexico. Today, she is CEHP’s full-time communications and outreach specialist, a dynamic role that includes original artistic production, institutional advising, interpersonal mediation, and cross-cultural translation in service of advancing environmental health literacy. Part vibrant patterning, part science illustration, and part surreal animation still, Quetawki’s eye-catching acrylic paintings employ networks of totems and animals of strength as metaphors for the body’s defensive cellular systems. This multilingual visual vocabulary speaks, simultaneously, to Indigenous populations navigating landscapes left scarred and contaminated by uranium mining and milling; to doctors, biologists, researchers, and social workers unschooled in Indigenous knowledge; and to outsiders learning about legacies of environmental racism in the American Southwest.

Alex Boeschenstein

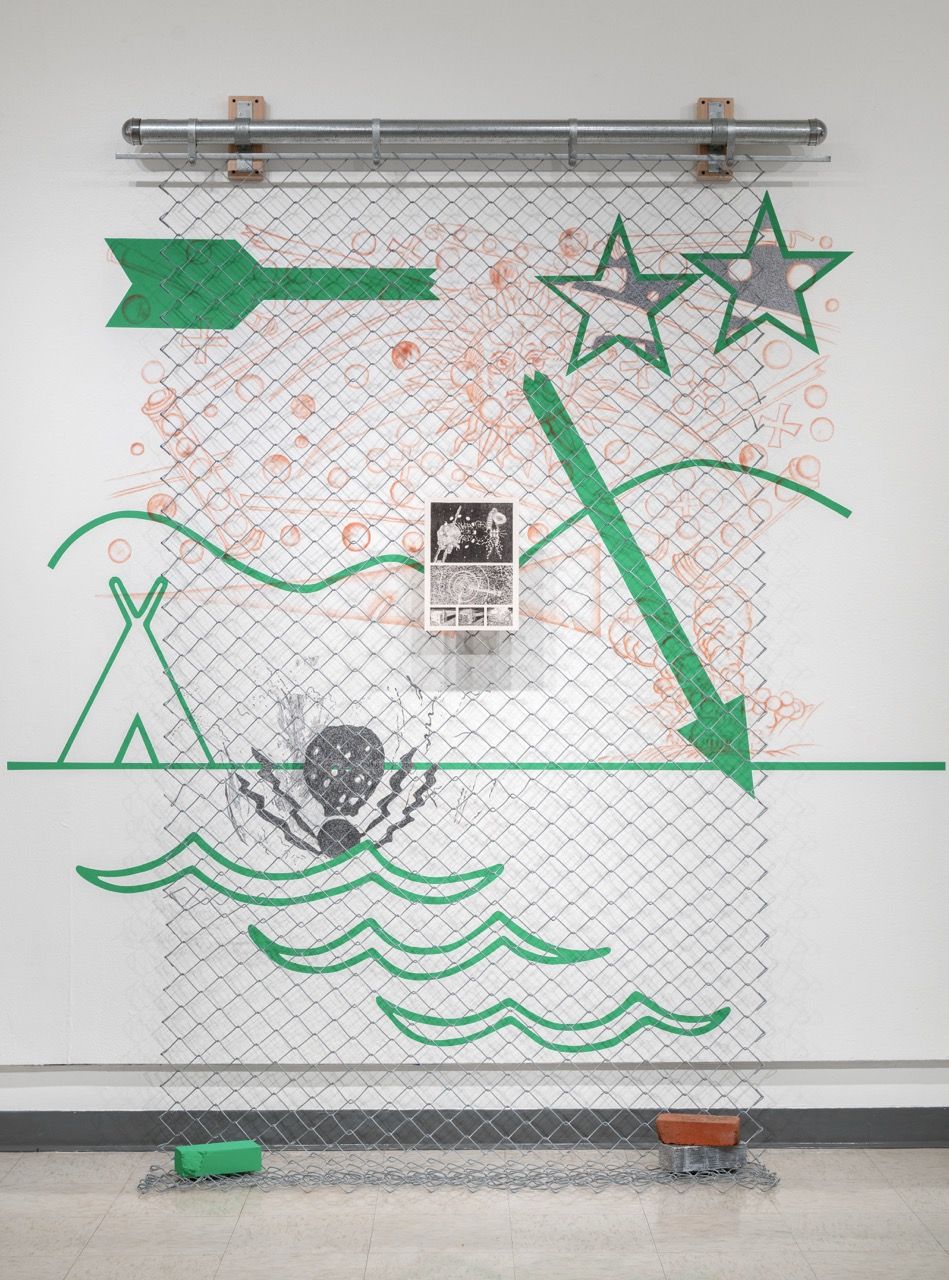

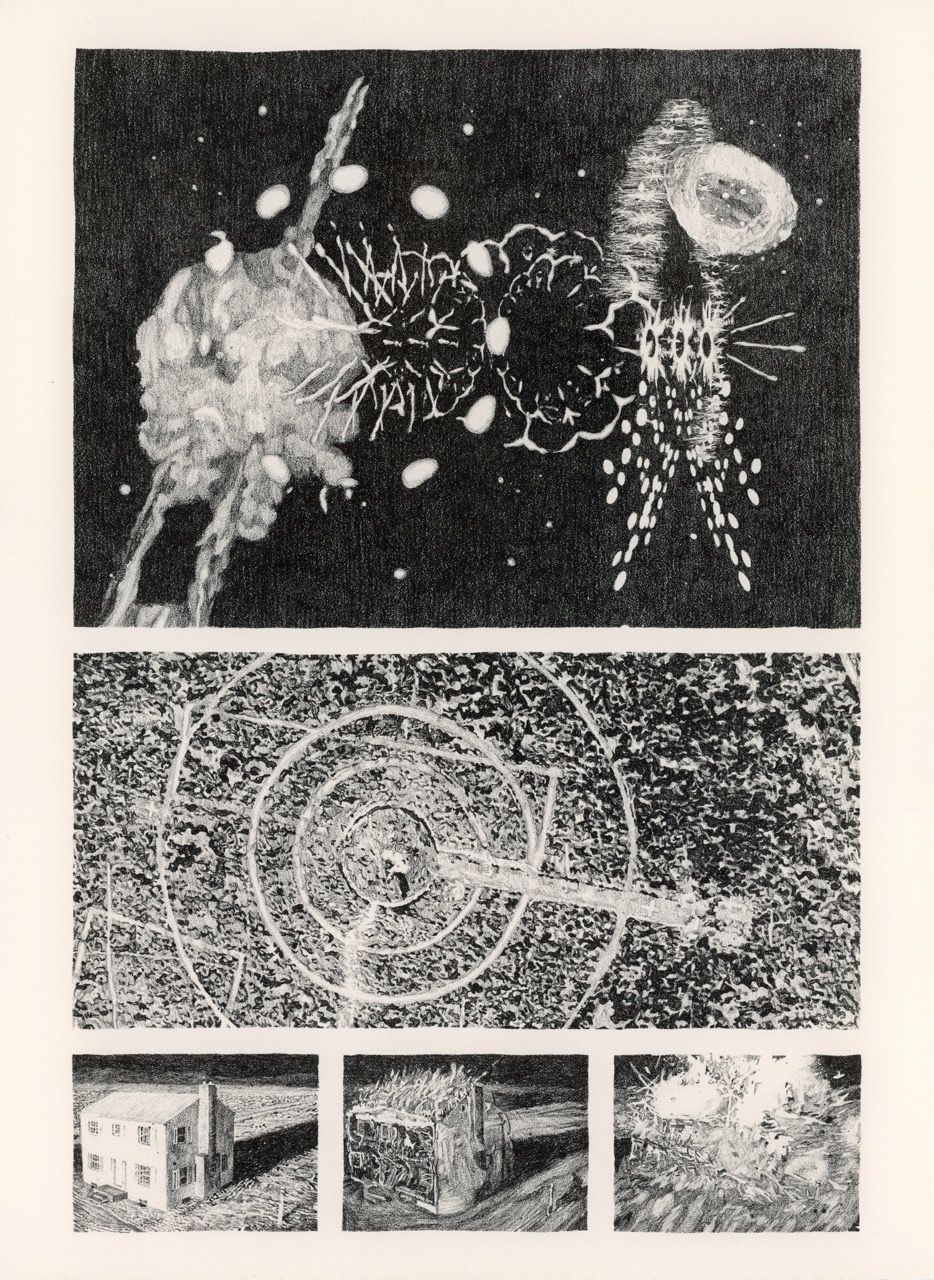

Detail of Alex Boeschenstein’s installation, “Perpetual Broken Arrow,” displayed in 2023 at the Roswell Museum in Roswell, New Mexico. Alex Boeschenstein

Alex Boeschenstein

Nothing arouses dread and creeping horror quite as intensely as imagining nuclear holocaust. And the fact that the southwestern United States is the unholy center out of which the nuclear age was spawned, the landscape takes on a completely different texture and valence.

While spending a year at the Roswell Artist-in-Residence program, Austin-based photographer and artist Alex Boeschenstein did a deep dive into New Mexico’s documented military and purported paranormal histories. An average day might include an hour’s drive to capture drone footage of massive earthen swastikas in the deserts east of Roswell (precision aerial bombing targets built during World War II), or a run into town to read through declassified government documents at the International UFO Museum and Research Center, or a road trip to the twice-yearly open house at the Trinity Test Site near White Sands.

Boeschenstein distilled his byzantine research into Visionary Rumor (2023), an expansive solo exhibition at the Roswell Museum named after analytical psychologist Carl Jung’s description of UFO-sighting phenomena. Multidisciplinary works like “Perpetual Broken Arrow” amalgamate highly detailed stone lithographic drawings of domestic nuclear tests; wall murals rendered with green-screen paint, graphite, and red iron oxide; and actual chain-link fencing, hardware, and found bricks. Boeschenstein’s satirical infographics point to horrifying nuclear-historical slapstick like the mannequins populating suburban “Down Town” homes who got nuked at the Nevada Test Site in 1955, or the alarming frequency of the titular “Broken Arrow,” a Defense Department term describing unplanned detonations, contamination, or even loss of nuclear weapons, warheads, or components that don’t instigate nuclear war (the Pentagon admits to 32 such incidences, though journalist Eric Schlosser, author of the 2013 book Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety, obtained a declassified document from the Defense Atomic Support Agency that listed hundreds more).

It was important to Boeschenstein that Visionary Rumor debut in New Mexico, the birthplace of American UFO lore and the country’s only “cradle-to-grave” nuclear state, where uranium was mined across the Navajo Nation, weapons were designed at Los Alamos and tested in the Tularosa Basin, and radioactive manufacturing detritus is deposited underground at the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant outside Carlsbad. With a healthy dose of curiosity and a little patience, visitors to Visionary Rumor could decode its tinfoil hat camouflage, uncovering a patchwork of symbols—a lexicon Boeschenstein calls the “Southwestern uncanny”—demonstrating that, in the United States, military truths are reliably stranger than any paranoiac political fictions spun by fringe conspiracy theorists.

Shanna Merola

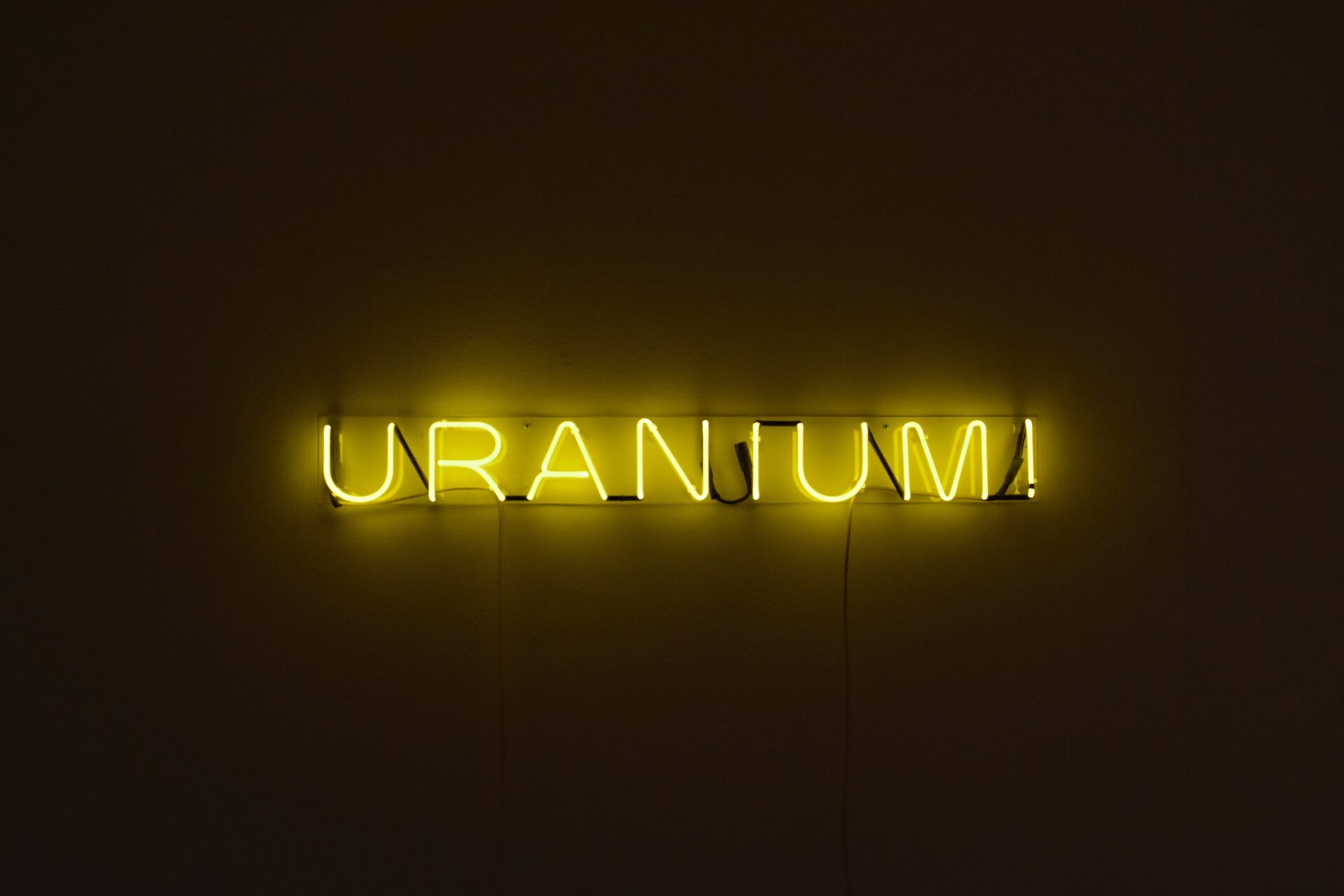

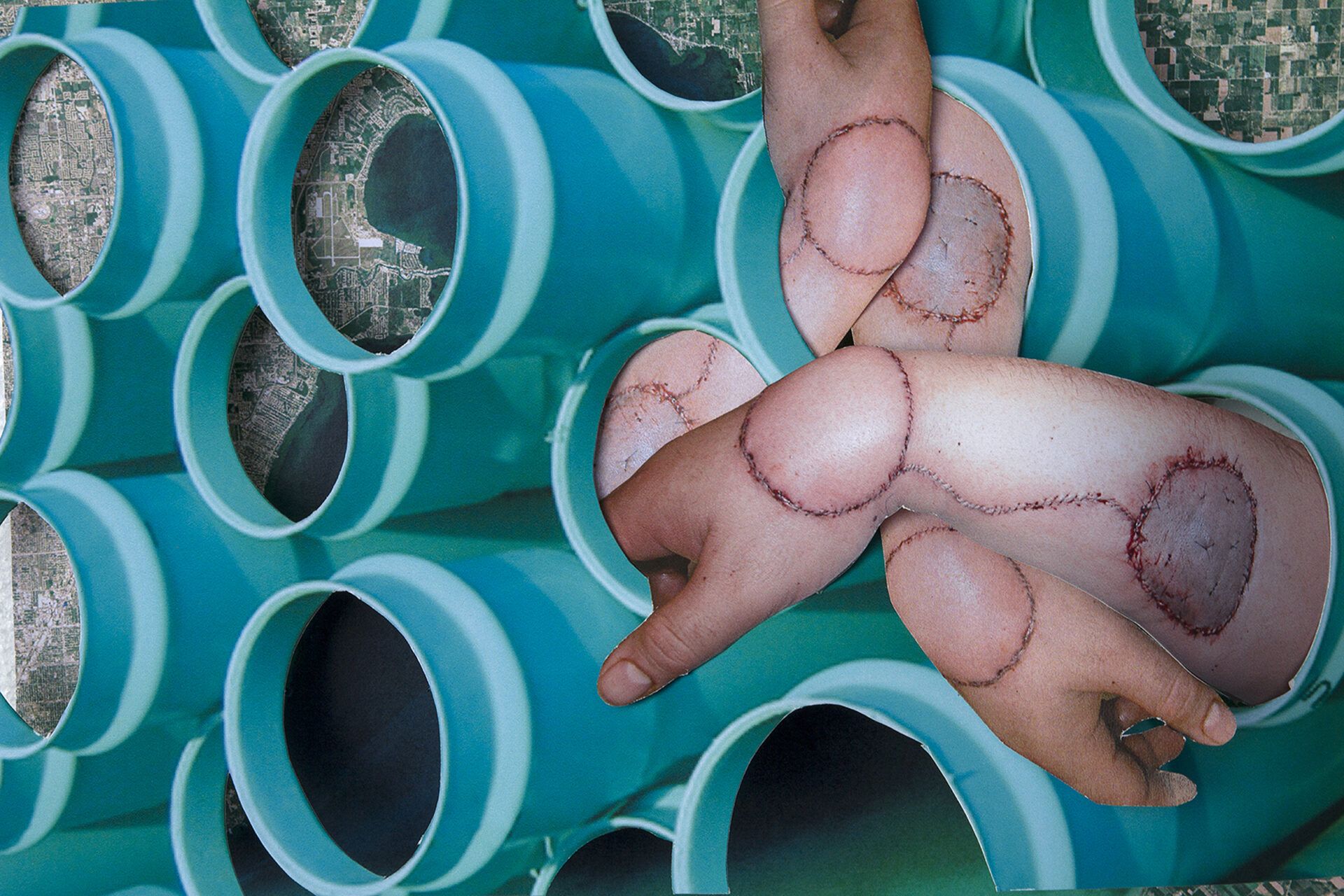

“Uranium” (2017), one of a series of works by Shanna Merola critiquing nuclear colonialism under the title We All Live Downwind. Shanna Merola

Shanna Merola

Anachronistic relics serve to memorialize the fears of a society on the perceived brink of impending annihilation. But the day-to-day horrors of the nuclear project wrought a more insidious violence.

In 2019, photojournalist, legal worker, and visual artist Shanna Merola was living on Detroit’s east side near a factory that was illegally dumping hazardous and radioactive waste. For years, she had been working on Love Canal, a collage project that unpacked histories of EPA Superfund sites, as well as two series critiquing nuclear colonialism: Nuclear Winter and We All Live Downwind. By cutting and layering appropriated and original imagery in the studio, Merola illustrated how radioactivity and other toxins quietly overlap geographies and timelines.

Then, that November, several hulking piles of improperly stored gravel aggregate caused a separate local industrial property contaminated with uranium and other pollutants to collapse into the Detroit River, just a short distance upstream from the city’s drinking water intakes and Lake Erie. The property was the former site of Revere Copper and Brass, subcontracted in the 1940s to fabricate components for the earliest atomic weapons using uranium and sundry toxic chemicals. Later, it manufactured uranium fuel rods. The surrounding area was identified as contaminated by the Energy Department as early as 1981, though radiation levels were determined to be below then-current criteria of concern. In 2011, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health reevaluated the site and determined that it posed a potential for significant residual contamination. The site collapsed into the river again in 2021.

Nuclear exploitation, Merola learned, had long ago reached the Great Lakes. Ongoing studio projects now had a local urgency, as Merola and other Detroiters grappled corporeally with the sprawling persistence of the US nuclear state revealing itself in new geographies, decades later.

As Christopher Nolan’s film Oppenheimer opened to packed theaters in the summer of 2023, three of Merola’s collages were exhibited in Las Cruces, New Mexico, just ninety-six miles south of the Trinity Test Site. The exhibition, Trinity - Legacies of Nuclear Testing: A People’s Perspective, was organized by the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium. As Merola’s perspective-bending studio output continues to engage nuclear colonialism on a global scale, the artist uses speaking engagements and activism to introduce audiences to regional groups fighting similar fights to the Trinity downwinders, like the Indigenous-led Citizens’ Resistance at Fermi Two (CRAFT), whose mission is to shut down a nuclear reactor on the shores of Lake Erie.

Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group

A self-portrait of the Don’t Follow the Wind collective in the Fukushima exclusion zone, 2015. Don’t Follow the Wind

Radiation levels measured during a visit by organizers of Don’t Follow the Wind to the Fukushima exclusion zone. Don’t Follow the Wind

Some of the Chim↑Pom collective’s taxidermized (and Pokemonized) “super rats” on a Tokyo street. Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group

Citizens of Japan have a patently different relationship with nuclear legacies than Americans. Hiroshima and Nagasaki remain the only two wartime nuclear weapons targets, and those catastrophic acts of violence and their aftermath echo across timelines for the island nation’s more than one-hundred-million residents. In 2005, a group of Tokyo artists formed Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group, a collective known for radical performance works that engage legacies of natural and human-made disasters including the atomic bomb and radioactivity. But where one might expect solemnity or soberness, Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group are irreverent and often sensational, earning them varying degrees of praise and condemnation. In response to the westernization of Tokyo—which yielded new consumption habits and mountains of trash—the collective captured “super rats” that have developed resistance to pesticides, stuffing and painting them to resemble Pikachu from Pokémon. The group describes the provocative taxidermy as “a metaphor for Japanese people living in the midst of radioactive contamination.”

Just months after the core meltdown at TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant that followed the March 11, 2011, Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group began secretly orchestrating their most audacious (and dangerous) undertaking. In early 2015, the collective unveiled Don’t Follow the Wind, a clandestine exhibition of commissioned works by a dozen artists that the collective and collaborators Kenji Kubota, Eva and Franco Mattes, and Jason Waite installed across four sites inside the 300-square-mile Fukushima exclusion zone. The exhibition, which included works by an international roster including Ai Weiwei, Taryn Simon, Kota Takeuchi, and Trevor Paglen, will only ever be publicly viewable if the area is declared safe to reinhabit. Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group has presented ancillary programming at various institutions, including the Watarium Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo, showing thematically related artworks and documentation from inside Fukushima, including a now-famous video where a cleanup worker points accusingly into a TEPCO security camera. The continued inaccessibility of Don’t Follow the Wind offers a stark reminder that no matter how resilient a nation is in rebuilding after wartime or energy-industrial disasters, the slow violence of radiation is ever-creeping.

Abbey Hepner

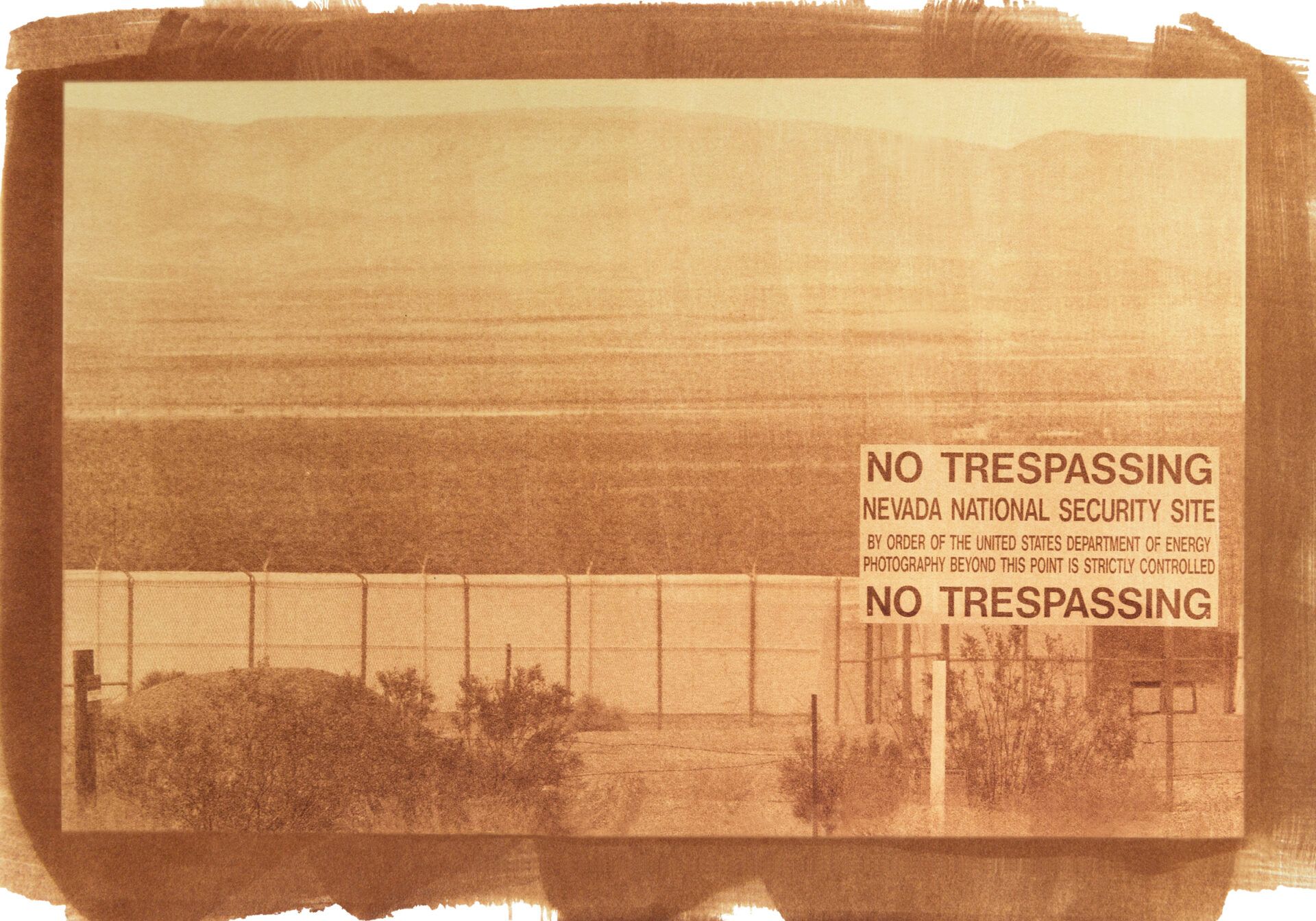

The Nevada National Security Site picture in one of the uranotypes (a photographic print created using uranium) from Abbey Hepner’s 2014 Transuranic series. Abbey Hepner

Abbey Hepner

She told me the color of the uranotype looked like the color of the sky after the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. That’s when I knew I needed this process to make this body of work.

The Fukushima disaster shook communities living near nuclear power facilities across the globe. Citizens were particularly vocal in Germany, where nuclear power provided 17 percent of the country’s energy at the time—within three months, the Bundestag had passed legislation to phase out nuclear power completely. Eight of the country’s reactors were shut down immediately. By April 2023, the last three plants—Isar 2, Emsland, and Neckarwestheim 2—went offline.

During the decommissionings, American artist Abbey Hepner (another descendant of Utah downwinders and one of the youngest members of the Atomic Photographers Guild) traveled by train across Germany, documenting closed and still-functioning plants for a video project called Scars on the Landscape. Hepner had previously lived in Japan, and participated in Fukushima cleanup efforts. During that time, she produced an eerily poppy photo series riffing on “nuclear mascots,” a Japanese cultural phenomenon deployed to soften the image of nuclear power facilities (and influenced, as was the postwar introduction of atomic energy more broadly, by the United States’ “Atoms for Peace” propaganda program). Hepner later broadcast an unsettling image of her own cartoonish nuclear mascot pointing ominously at the viewer—like the cleanup worker at Fukushima—on a digital billboard at Shibuya Crossing in Tokyo, the busiest pedestrian intersection in the world.

Hepner’s project Transuranic (2014) was more traditionally representational, consisting of photographs captured at every nuclear site in the western United States that transports radioactive waste to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico. But Hepner employed an unsettling material twist: The photographs were uranotypes, an obsolete 19th-century process that uses uranium instead of silver to produce an image. These complicated meta-works are radioactive, evidenced by the ticking of Geiger counters that were installed in the gallery beside them.

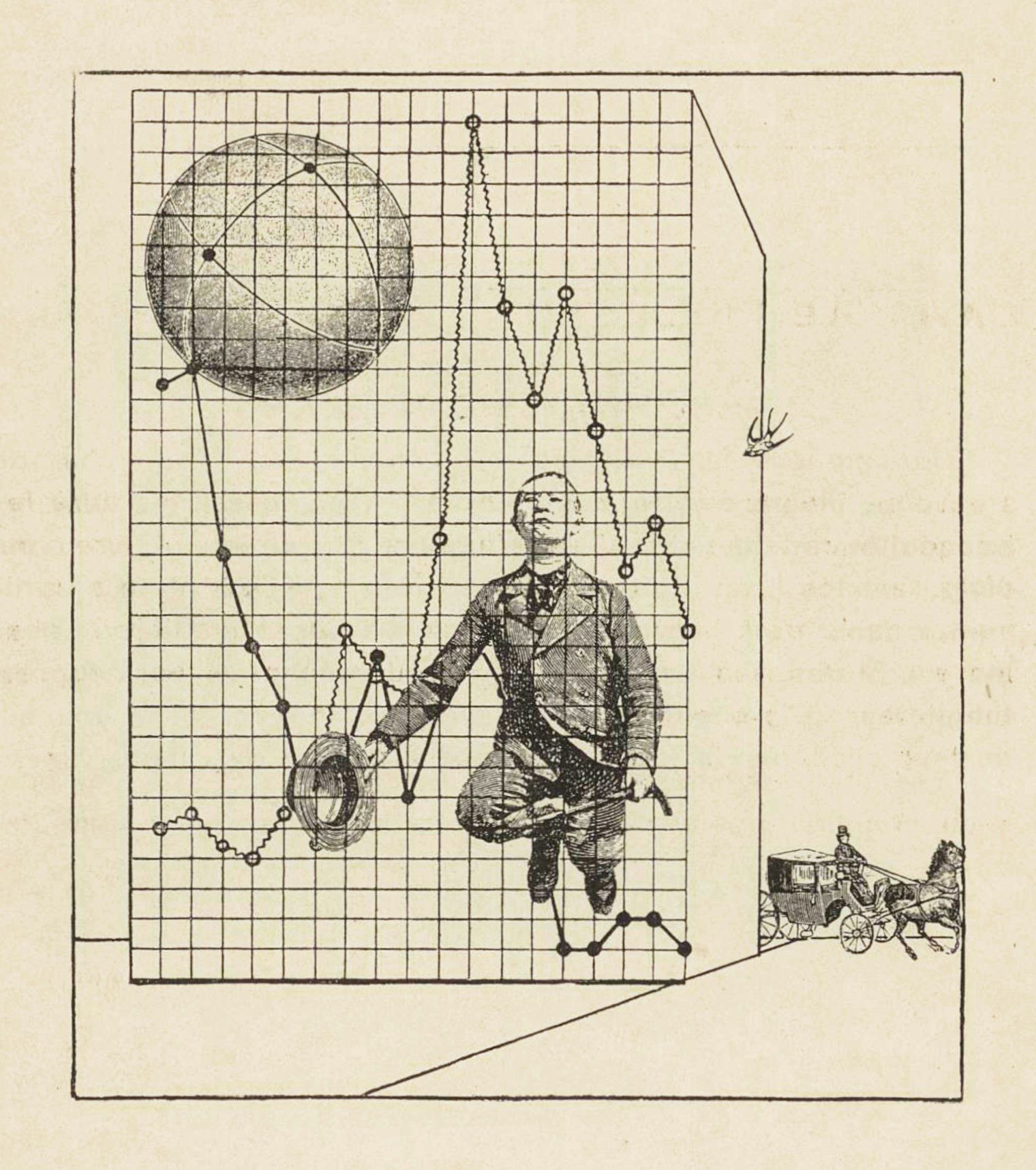

In the wake of the paradigm-shifting existential horrors of mechanized death introduced in World War I, a loose group of artists coalesced around the avant-garde Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich. Dubbing themselves the Dadaists, the interdisciplinary misfits embraced the absurd and the illogical to lampoon institutions of government and capital. They championed poetry, chance, collage, and noise. Disconnected chapters emerged in Berlin, Paris, and New York, and later in Eastern Europe and Japan. Although short-lived (art-historically speaking) and scantly organized, the half-life of their artistic influence has proved remarkably long, visible in the Merry Pranksterdom of 1960s radicals, the salacious pratfalls of Jackass, and multiple Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group stunts. Reality, the Dadaists proposed, isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

A collage by Dada artist Max Ernst, from Les Malheurs des Immortels, a 1922 book by Ernst and Paul Eluard. As Daisy Saisbury writes, “The book’s formal experimentation captures something of that broader zeitgeist: sifting through the fragments of what came before, and trying to assemble something new of value.”

So many facets of the nuclear age cannot be made visible, either due to their nanoscopic physicality or their manifestations as psychological phenomena. Clearly, skillful photographic, film, and video documentation remains essential, especially to make sure that its victims are seen and heard. But as 21st-century artificial intelligence platforms learn to fabricate images and videos with increasing fidelity, skepticism about visual media will deepen. It stands to reason, then, that the efficacy of the empirically motivated artistic strategies of the 1980s and 1990s—like Peter Goin’s “behind-the-fence” landscape photographs of Bikini Atoll, Yucca Flat, and Hanford, or Kenji Higuchi’s documentation of workers cleaning up after “clean energy”—may wane.

Paradoxical times call for paradoxical art, and the interdisciplinary, experimental tactics wielded by the next generation of atomic artists might compete more effectively with the increasingly devastating absurdities of this current timeline. If we are indeed experiencing an epistemological crisis, where there is no longer a shared sense of a baseline reality, then the anti-growth, semi-Dadaist artistic technologies of paradox, abstraction, and play seem like productive pursuits. The average viewer might, in the very near future, find speculative and science fictions, Indigenous cosmologies, poetries of paranoia, surrealist collaging, dangerous art materials, and logic-defying site-based interventions easier to comprehend than a seemingly straightforward aerial shot of a pockmarked bombing range.

Design: Thomas Gaulkin

Get alerts about this thread

0 Comments

Oldest