Once seen as a symbolic protest, the nuclear ban treaty is growing teeth

By Olamide Samuel | April 3, 2025

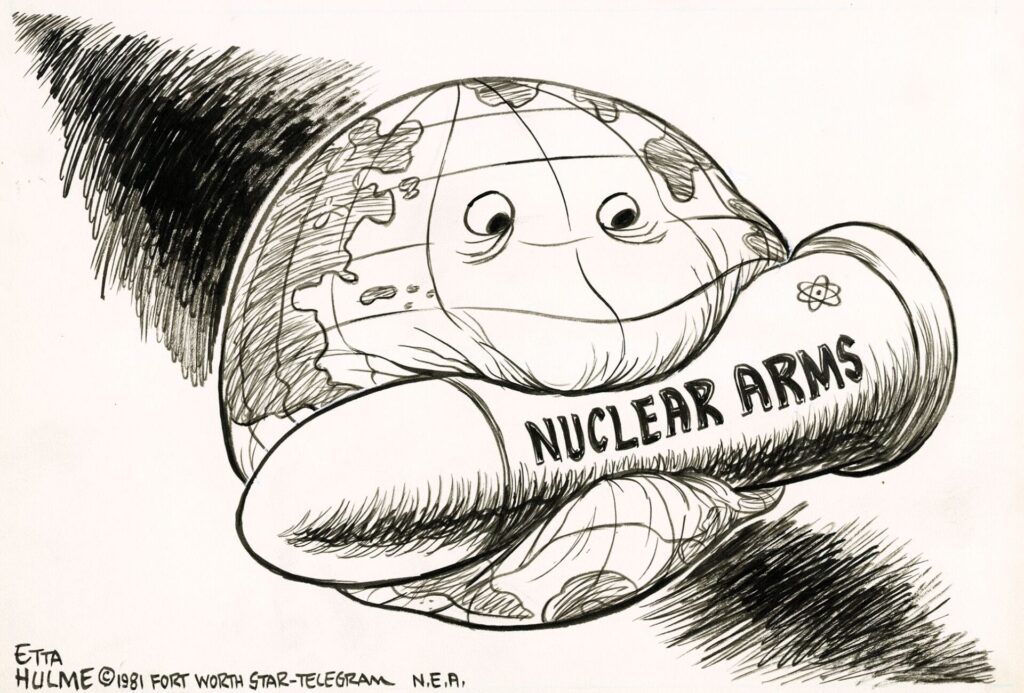

This cartoon by Etta Hulme appeared in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram on Nov. 29, 1981. (Etta Hulme / University of Texas at Arlington Libraries, Special Collections; CC BY-NC)

This cartoon by Etta Hulme appeared in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram on Nov. 29, 1981. (Etta Hulme / University of Texas at Arlington Libraries, Special Collections; CC BY-NC)

Amid Russia’s war in Ukraine, nuclear saber-rattling, and the United States’ sudden turn away from its longtime transatlantic alliances, fears of nuclear conflict are leading European governments to pursue new ways of protecting themselves. Last month, European Union leaders approved a massive new militarization independent of US support; France is considering extending its own nuclear deterrent over the whole continent; and some countries have resurrected Cold War-style civil defense plans. Germany, for example, has piloted a smartphone app to direct citizens to the nearest bomb shelter, while Norway is reintroducing a policy that requires bomb shelters in all new buildings. And the EU has called on its citizens to stockpile 72 hours-worth of supplies in the face of “emerging threats.”

But what of the rest of the world? Even so-called “limited” use of nuclear weapons is unlikely to stay limited to one region; a nuclear war of any kind will almost certainly not. Radioactive fallout, climate disruption, and economic shockwaves can cross borders and continents, meaning no country truly stands apart from the danger. Nations far from the blast zone—whether or not they participate in a nuclear conflict—could still face crop failures, mass migrations, and other cascading disasters. In short, if nuclear weapons are used anywhere, everyone’s safety is at risk.

Survival requires attention to larger, systemic issues—international cooperation, governance of risk, and global diplomacy—that offer more meaningful protection than any nuclear weapon or bunker can. The popularization of civil defense discussions, while potentially comforting in their simplicity, in fact exposes a collective failure to tackle the underlying causes of these fears. Humanity’s long-term survival depends on global efforts to reduce the risks that threaten us.

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) is one such global effort. Critics initially dismissed the treaty as a purely symbolic gesture—a “protest treaty” unlikely to affect real-world security. But recent developments suggest the ban treaty is growing some teeth. In November 2024, TPNW states prevailed on the United Nations General Assembly to launch a comprehensive scientific study on the effects of nuclear war. And at the treaty members’ most recent major meeting in March—which I attended—a detailed report articulating the security concerns of non-nuclear countries took center stage at the UN’s New York headquarters.

These steps represent a pivotal milestone for the treaty, which is now emerging as a key venue for serious diplomatic deliberations about nuclear security at a critical moment—a moment when many traditional arms-control agreements and forums have either collapsed or stalled. Thanks largely to the TPNW, a new space has opened up, in which frank and thorough examination of the catastrophic human and environmental consequences of nuclear weapons use can help expose the risks of nuclear deterrence itself.

Fixing the nuclear diplomacy gap. For decades, global arms control agreements have struggled to ease the fears of countries without nuclear weapons. The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)—essentially a bargain between nuclear haves and have-nots—promised eventual disarmament, but progress has been glacial. Major powers have been backsliding: The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty is history, and the last US-Russia arms pact, New START, is on life support and set to expire in less than a year. Traditional forums like the UN Conference on Disarmament have been deadlocked for years.

All the while, the security concerns of non-nuclear weapon states have been largely ignored. In meetings of treaties like the NPT, discussions tend to focus on keeping nuclear weapons out of the wrong hands—but what about the danger posed to everyone by the weapons the great powers already have? For a country with no nukes, the prospect of radiation drifting across its borders or a “nuclear winter” causing famine remains an existential threat. Yet, in the old forums, nuclear-armed states and their allies have often brushed aside these worries, insisting that their deterrence doctrines keep the peace.

Against this backdrop, the countries party to the TPNW have shifted focus to address these issues head-on. At the treaty’s third meeting of states parties in early 2025, they unveiled a report on the security concerns of states living under the shadow of nuclear weapons. This move signaled the ban-treaty states aren’t just pursuing disarmament ideals but are also eager to articulate their own concrete security priorities in a world with ongoing nuclear threats.

The report synthesizes the collected input of TPNW states, experts, and non-governmental organizations after the treaty’s second meeting at the end of 2023. The report’s findings challenge the notion that states consider deterrence a source of stability and security. The report notes that TPNW states consider that “nuclear deterrence is a dangerous, misguided and unacceptable approach to security.” It then recasts humanitarian impacts of nuclear weapons as core national security concerns for non-nuclear nations and explains why: a single nuclear detonation wouldn’t just devastate the immediate target; it could knock out electrical grids with electromagnetic pulses and blanket entire regions in radioactive fallout. And the damage wouldn’t stop there. The authors describe the “transboundary” impacts: mass migrations of refugees fleeing irradiated zones, the breakdown of emergency services, global supply chains for food and medicine ruptured, and the potential collapse of public order far from ground zero.

In other words, nuclear war anywhere endangers people everywhere—and since the existential security of the world’s non-nuclear states continues to be entirely determined by the security priorities of a few nuclear powers, the report reframes those humanitarian consequences as fundamental security concerns for every state: “From the perspective of States parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, policy decisions regarding nuclear weapons should be based primarily on the available scientific facts about the consequences and risks of nuclear weapons rather than on the uncertain security benefits of nuclear deterrence.”

What we know and what we don’t know. The last UN-mandated study on nuclear war impacts, conducted by the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) in 1988, was a landmark assessment that brought scientific consensus to the global threat of nuclear winter. However, the study is now outdated. In the 37 years since, we have made significant advancements in climate modeling and environmental science in ways that allow for higher-resolution simulations of atmospheric effects, such as those caused by soot and dust following nuclear detonations to better simulate the cascading impacts of nuclear conflict.

Subsequent studies have examined the global impacts of nuclear war, including influential work by Alan Robock and Brian Toon in the 2000s and 2010s on cooling and agricultural effects, and a 2019 study projecting severe global food and health consequences from an India-Pakistan nuclear conflict. Although these supplementary independent studies are important, there is still a lack of broader appreciation of the full-scale impact of nuclear detonations.

Our ignorance is, to some extent, by design. The effects of nuclear war are often viewed (especially by nuclear weapon states and their allies) through a military lens, focused primarily on the immediate consequences of a nuclear strike, without fully accounting for the long-term environmental, societal, and human impacts.

To address this gap, members of the TPNW’s Scientific Advisory Group recommended in 2023 that the UN mandate an assessment of the effects of nuclear war. In November of last year, a resolution establishing an independent Scientific Panel on the Effects of Nuclear War was brought to the General Assembly, cosponsored by 20 TPNW states. Apart from the nuclear weapons states, the resolution received overwhelming support: 144 countries voted in favor, 30 abstained.

Of the nuclear weapon states, France, the United Kingdom and Russia voted against the resolution; the United States did not record a vote; and with the exception of China, which voted for the study, other nuclear states (Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea) all formally abstained.

In explaining their votes, both France and the UK curiously stated that a scientific panel would not provide any “new” insights into our understanding of the effects of nuclear war. The UK, in particular, raised concerns about the budgetary implications, despite the panel’s total operating cost being only $300,100—equivalent to the cost of operating the UK’s nuclear deterrent for two hours. Imagine then, if this panel (in conjunction with the World Trade Organization) were to reveal the economic impact of a limited nuclear war on global socioeconomic systems? Such findings are very feasible, given the broad mandate of the scientific panel: Article 7 of the resolution calls upon a range of global agencies to support the panel’s work beyond obvious ones like the International Atomic Energy Agency—including those that look at financial, health and agricultural effects, like the World Health Organization, the World Food Programme, the Food and Agricultural Organization, and the World Trade Organization.

Deterrence as science denial. Studies on self-deterrence have shown that political leaders’ decisions about nuclear weapons aren’t just shaped by military strategy—they’re deeply influenced by the moral and psychological weight of such decisions. Many leaders may hold back from using nuclear weapons not because they fear defeat, but because they want to maintaininternational legitimacy, avoid alienating allies, and protect the global non-proliferation system; and because they understand some of the devastating, irreversible consequences, especially for the environment and future generations. The idea of being the person who triggers the end of civilization or leaves the planet in ruins is something most leaders are reluctant to face.

Even Donald Trump has acknowledged the dangers of nuclear weapons, as when he said in October 2024, “getting rid of nuclear weapons would be so good … because it’s too powerful, it’s too much,” and his more recent statements suggesting that “the destructive capability is something that we don’t even want to talk about” and that the United States, China and Russia could denuclearize.

This, perhaps, explains why updated studies on the societal impact of nuclear war are so politically charged, and why some states opposed the new study (which after all, is just a study). To acknowledge the global societal impact of nuclear weapons is to confront the unmanageable consequences of their use and challenge the foundations of deterrence itself. As Robock notes in an interview with the Bulletin, if the US nuclear establishment “acknowledged the horrific impacts of nuclear war, their theory of deterrence would fail.”

Survival beyond bunkers. Ultimately, humanity’s safety depends not on geographical location, but on global efforts to reduce risks. Since its entry into force, the TPNW has begun to emerge as an unexpected yet indispensable forum for questioning whether the logic of deterrence itself makes sense in a world that cannot afford the consequences of failure.

Illuminating the true impacts of nuclear war has a way of cutting through abstract theories — as it did in the 1980s when public horror at nuclear winter nudged even hardline leaders toward arms control. In the same way, the convergence of the UN’s new impacts study and the TPNW’s security initiative could shatter any lingering illusion that nuclear war can be “managed.”

In just four years, the TPNW has evolved beyond the caricature of a “protest treaty.” It offers something the traditional forums often cannot: a willingness to confront the uncomfortable truths about nuclear weapons, from their humanitarian consequences to the fragility of deterrence itself. The TPNW is not about dismantling the system overnight; it’s about ensuring we have the courage and the foresight to imagine a future where nuclear arsenals—and the assumption that we need them—no longer exist.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: International Security, TPNW, deterrence theory, nuclear ban treaty, nuclear weapons

Topics: Nuclear Weapons, Opinion

While working in nuclear warfare planning over 45 years ago I was taught … “never in the history of mankind has there been an arms buildup that was not followed by a war.” One could say that the cold war saw a massive arms buildup that did not result in massive war … but there is the belief that the cold war never ended .. it just transmuted… with more players who have developed the weapons of mass destruction (WMD) technology. Further to this understanding I learned in a second-year social psychology course that “the presence of weapons causes aggression.”… Read more »