The 15-minute interview: Ambassador Harold Agyeman, chair of the third preparatory committee for the NPT Review Conference

By John Mecklin | April 24, 2025

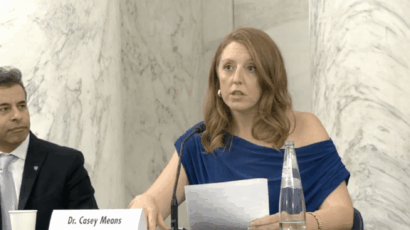

Ambassador Harold Agyeman of Ghana

Ambassador Harold Agyeman of Ghana

Even as President Trump’s tariffs, deportations, and insults occupy news headlines, nuclear weapons have gained a measure of public attention of late. The United States and Iran have begun new talks about the Iranian nuclear program. And the United States and Russia continue to circle one another, negotiating—so far inconclusively—about an end to the war in Ukraine and a revival of arms control talks in advance of next year’s expiration of New START.

Meanwhile, the process by which member countries manage the Non-Proliferation Treaty, or NPT—the remarkably effective international check on the spread of nuclear weapons—plays out largely unremarked in the general press. Those countries have been setting the agenda for an NPT Review Conference scheduled for next year in a series of preparatory committee meetings, the third of which begins on April 28. Ahead of that meeting, I spoke with Ambassador Harold Agyeman of Ghana, the chair of that third so-called prepcom. A transcript of our discussion, lightly edited for readability, is below.

John Mecklin: Policy experts will probably know you and everything about the Non-Proliferation Treaty process. But the Bulletin has 600,000 readers a month, and a lot of them won’t. So why don’t you, just for a start, explain the preparatory committee process and how you fit into this third preparatory meeting between the NPT review conferences.

Harold Agyeman: Thank you very much, John, and many thanks for doing this interview with me. The nonproliferation of nuclear weapons treaty, or the NPT, was negotiated and agreed in 1967; it came into force in 1970. And it was a treaty that was elaborated or developed essentially to stop the risk of proliferation of nuclear weapons and also to reverse the nuclearization that are taking place at the time, and also, lastly, to advance the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. And so as part of the articles of the treaty, it has a five-year review conference, and every five years, state parties are expected to meet and review the operations of the treaty and also to make recommendations to look into the future.

In 1995, in the NPT review and extension conference, the treaty was indefinitely extended. And as part of that process, also we have in place these preparatory committee meetings to prepare for the review conferences. And so out of three preparatory committee meetings that are held, mine will be the third that we hold before the 2026 Review Conference.

Mecklin: I guess in general, the aim is to come up with some sort of consensus report to put on to the Review Conference in 2026. Do you expect there to be that kind of consensus report from your preparatory committee meeting? Or can you tell at this point?

Agyeman: The expectation is that for the third and final preparatory committee meeting, there are two sets of mandates. The first mandate is procedural, to ensure that we prepare all the procedural issues necessary for the review conference to take place successfully in 2026—things like adopting the provisional agenda, endorsing the president of the review conference, allocating items that will be considered under the Review Conference to the main committees. Those ones are much easier to achieve consensus over and to set the framework for constructive deliberations at the Review Conference. The other element is for the preparatory committee to be able to agree to the summary report of the preparatory committee, as well as to make some recommendations to the Review Conference. Historically, this has been very difficult to achieve. Nonetheless, what is important is that if a good process is undertaken and constructively so, then it enables a review conference to have as a basis some elements that already state parties are able to see that there could be convergence or agreement over and areas where there may be divergence, which require a bit more work.

Mecklin: Those areas where there might be convergence, can you talk a little bit about them? What in general do you see as the main things that would be discussed?

Agyeman: The Non-Proliferation Treaty has three pillars. One is disarmament, another is on nonproliferation and sometimes, if it’s extended a bit, on safeguards, and the last is on peaceful uses of nuclear energy. On peaceful uses of nuclear energy, there’s a lot of convergence around many of the elements there. The expectations that state parties are coming into the third preparatory committee meeting with are that the inalienable rights of the nonnuclear weapons states to the peaceful use of nuclear energy should be advanced.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has done a lot of work in terms of the application of nuclear technology for things like radiology treatments, zoonotic applications, issues relating to water resources and their impact on climate change, and essentially, peaceful uses to advance the implementation of the sustainable development goals or development agenda broadly is one area where I believe that there’s a bit of convergence. Of course, that requires that there’d be a bit more resources and attention devoted to the peaceful uses application [of nuclear technology] through international cooperation arrangements.

The other issue that I feel that there’s some convergence around is that the risk of nonproliferation should be clearly stated as something that none of us want to see. And so that is something that I believe, as a base, there is some convergence around. And on nuclear disarmament, I believe that the convergence relates to the expectation most state parties have that the obligations under the NPT, as well as the commitments that have been made in other review conferences, including in 2000 where 13 practical steps were adopted, or in 2010 where a 64-point action plan was adopted should be upheld and not jettisoned. And so these are some of the baseline convergence issues around which we would seek to develop additional areas of agreement to move the process forward.

Mecklin: In the past, there has been some tension around the disarmament element of the treaty, and there has been of late some tension between some supporters of the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons and the NPT. And I just wanted to hear you talk a little bit about how you see those two treaties either working together or not working together.

Agyeman: I very much hear the issues that you raise. And I think disarmament is always controversial, because the nuclear weapons states have advanced the argument that their possession of nuclear weapons has constituted the basis for deterrence and has provided some form of global stability. Of course, for non-nuclear weapon states, this argument is not valid, and the view of non-nuclear weapon states is that there should be a strong effort towards disarmament, as had been anticipated by the treaty itself when it was being evolved. And that is the reason why many non-nuclear weapon states are also members of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, and they believe that because of the lack of progress by the nuclear weapon states, there’s a need to come to a normative agreement around the principle that nuclear weapons should not exist and should never be contemplated for use.

The argumentation that I think is relevant in this respect to make is that a lot of countries have already committed to the TPNW, and the treaty is a very strong check on further proliferation, because once a country or a state has voluntarily agreed that it is not going to possess nuclear weapons and has committed to some additional treaties besides the NPT, this is a very strong indication that the framework is being strengthened. And I therefore see [the TPNW] as a very useful complement to the NPT, rather than a competitor to the NPT. The NPT, of course, is the cornerstone for the nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation regime, and most of us understand that.

Mecklin: So I have a final question. I’m not sure whether you’re going to want to answer it or not, but past recent review conferences have produced no consensus document, and that’s been presented as some kind of failure of the conferences. Is there something short of a consensus document coming out of the review conference that could be some sort of progress? Could there be, rather than a complete consensus statement, other things, smaller things that are agreed to, or general directions? I’ve noticed in reading around that gift basket diplomacy has been mentioned, and I’ll just leave it there for you to talk about what you see as likely or possible things coming out of the review conference.

Agyeman: My expectation is that, unlike the 2015 or 2022 review conferences, the 2026 review conference will come out with a consensus outcome document. By the process that the NPT regime has had, review conferences are supposed to come out with consensus outcome documents. Of course, consensus is a term of art that has evolved over the years from broad agreement to the situation where now in many of the multilateral fora it is interpreted more in the context of unanimity. But between the two extremes, there are also situations where state parties or member states have decided that they will disassociate from specific paragraphs in a text that they do not necessarily agree with. And so there are different ways by which we can find agreement when that commitment from state parties exist.

On the issue of an outcome document, I must say that from 2000, 2005, and 2010 we’ve had different forms; even in 1995 we had different forms of outcome documents. And so, as you allude to, there could be a way by which, where there’s agreement, we could fashion the outcome in a way that may be acceptable, without necessarily binding ourselves into a certain set form. And that is something that I’m sure that the president of the Review Conference in 2026 will be very much seized with.

But having said that, in recent times there has been a very strong shift of interest by state parties on elements related to the 1995 requirement to find a way to strengthen the review process. And so from the 2022 working group for the strengthened review process, there had been some common elements that were more or less generally agreeable to many state parties. And my expectation is that we will be able to carry those forward into some form of decision in 2026 in a manner that will be able to move the process forward.

Having said that, let me also indicate that the treaty itself is not necessarily related to any of these processes. The obligations that state parties have continue to exist: not to proliferate, and to disarm. And so regardless of whatever outcomes that one may have under the review process, the existing obligations nonetheless continue to exist. Of course, a third consecutive failure (to produce a consensus statement), which is unprecedented, will have an impact as to how state parties view the treaty. But we should try to also separate the process from the obligations that have been agreed to by member states in the 1967 treaty.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.