What Sweden, Finland, and Poland can teach the United States about confronting Russia’s nuclear threats

By Marlena Broeker | April 11, 2025

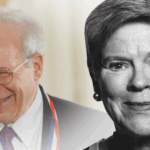

President Trump met with Polish President Andrzej Duda on the sidelines of the CPAC conservative conference in Maryland on February 22, 2025. Trump praised Poland’s commitment to increase its defense spending and said the meeting reaffirmed the close alliance between the United States and Poland. White House photo by Molly Riley

President Trump met with Polish President Andrzej Duda on the sidelines of the CPAC conservative conference in Maryland on February 22, 2025. Trump praised Poland’s commitment to increase its defense spending and said the meeting reaffirmed the close alliance between the United States and Poland. White House photo by Molly Riley

From the minute Russia put its nuclear forces on high alert after invading Ukraine in February 2022, Moscow has sought to limit NATO’s military assistance to Ukraine by turning decisions on Western support into questions about the potential for nuclear escalation. Three-plus years into the war, Washington’s struggle to support Ukraine in the face of Russian nuclear blackmail has limited Ukraine’s ability to defend itself. It has also encouraged the use of nuclear coercion as a tool of conventional war.

During the Trump administration, financial support for Ukraine has fluctuated, and questions remain about future assistance and a possible peace deal negotiated by the United States. Meanwhile, countries on NATO’s eastern flank have taken a different approach. Despite being on Russia’s doorstep and at risk from nuclear and conventional escalation, Sweden, Finland, and Poland used Russian threats to inform their support of Ukraine rather than condition it.

The United States should learn from how countries closest to the conflict calibrate their support of Ukraine and response to Russian nuclear threats. These lessons can help Washington develop a strategy that effectively balances a dynamic response to Russian escalation with signaling that such escalation will not win the war.

Challenging Russian nuclear rhetoric. Although Poland would be on the front lines of an expanded Ukraine conflict, Warsaw remains among Ukraine’s strongest advocates. Poland consistently challenges the United States to take stronger action to counter Russian nuclear blackmail; it has repeatedly stated its willingness to host US nuclear weapons and called on the United States to approve long-range Ukrainian strikes into Russia months before Biden gave permission for them. Many Poles remember Soviet occupation during the Cold War and grew up with stories of Russian rule before World War I.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was the impetus for Sweden and Finland to break decades of non-alignment and apply for NATO membership in May 2022. Although Russia has attempted to portray its aggression as a response to a supposed “threat” from NATO’s enlargement, the Nordic states clearly saw that the issue was whether Ukraine and NATO would accept the use of violence to change borders and governments. When Russia tried to prevent formerly neutral countries from joining NATO by threatening to expand the war and deploy additional nuclear weapons in the Baltic region, Sweden and Finland calculated that the risk of joining NATO was smaller than the danger of Russia achieving its goals through aggression. Russia’s threats only served to reinforce their relationship with NATO, motivating them to finally join the alliance.

The lesson is not that Sweden and Finland don’t take Russian threats seriously—rather, the opposite. Experienced neighbors, Sweden and Finland carefully observed growing Russian aggression, and Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula deepened their understanding of the threat’s gravity. By 2022, they were ready to activate newfound public support to quickly build security against Russian threats. Knowing a NATO application would get Moscow’s attention, Sweden and Finland took a decisive step that demonstrated both their commitment to Ukraine and their resistance to nuclear blackmail.

Washington should take note. Its glacial approach to approving aid and lifting restrictions on US-supplied equipment sent a message that nuclear threats are effective and reinforced Moscow’s willingness to use them. There is good reason to take nuclear threats seriously, but allowing the threatening state to dictate policy through threats invites more such behavior. The danger of normalizing nuclear threats in conventional war will only grow as the Trump administration turns its focus toward a potential peace deal in Ukraine.

Washington can rebalance its approach to nuclear blackmail by listening to the countries closest to the war when deciding on further support for Ukraine or moving toward a potential peace deal. This will help the United States create a cohesive response to Russian escalation tactics while showing the Kremlin that nuclear coercion will not win the war. With President Trump enjoying good relations with the Polish government, and Poland reorienting its security policy toward Sweden and Finland, there may be space to deepen coordination on future Ukraine assistance.

The path toward a lasting peace. For Ukraine, NATO, Europe, and ultimately the United States, bringing about a lasting peace means supporting Ukraine in maintaining its independence and preventing Russia from claiming any victory that emboldens further conquest. As Polish President Andrzej Duda stated on January 21, “this is like a comeback of imperialism, Russian imperialism, and we do not want to have that.”

Trump and the countries on NATO’s eastern flank agree on one thing: They all want Europe to commit itself more seriously to its own security, and this could be the perfect opportunity for them to do so. NATO’s current leader in defense spending, Poland, has backed Trump’s call for NATO members to increase their defense spending to five percent of their gross domestic product (GDP). Poland will spend 4.7 percent of its GDP on defense next year, and on January 27, Lithuania and Estonia became the first two NATO countries to pledge that they will spend more than five percent. Additionally, Poland and the Baltic-Nordic states have already tightened their cooperation as they counter suspected Russian hybrid warfare in the Baltic Sea, such as the sabotage of undersea cables.

On February 12, Trump called Russian President Vladimir Putin to kickstart what he said would be the beginning of peace negotiations in Ukraine. So far, the United States’ NATO allies and, even more worryingly, Ukraine, have been consistently sidelined and even demeaned by the United States during the ongoing negotiations. Given that this war has been fought on Ukrainian soil and with Ukrainian lives, and that bordering countries will presumably be asked to shoulder peacekeeping efforts in a deal, limiting Ukraine’s and Europe’s roles in creating peace now will only diminish their ability to take control of their own security and maintain peace later.

If the Trump administration wants to bring the Ukraine conflict to a permanent end and prevent nuclear threats from dictating the relationship between Russia and the United States, it would do well to listen to its front-line allies. Likewise, Poland and the rest of NATO’s eastern flank have much to gain by getting Washington to listen to their concerns and expertise in any potential deal.

Restraining nuclear coercion for global security. With nuclear blackmail in play, both continuing support and cutting back support for Ukraine have the potential to raise nuclear danger. The United States must strike the optimum balance between backing Ukraine’s self-defense and avoiding actions that could push Moscow closer to using nuclear weapons. In practical terms, this means assisting Ukraine in ways that do not cross Russian red lines—such as the involvement of NATO troops—while also working with Ukraine and its NATO allies to promote the narrative that Ukraine has won the war by maintaining its independence. Preventing nuclear war means preventing the use of nuclear weapons as both blackmail and bombs.

The alternative is teaching Moscow and the rest of the world a dangerous lesson: having nuclear weapons is a big advantage in conventional war. With the United States nervously eyeing the partnership between Russia and North Korea, struggling to referee the conflict between Iran and Israel, and heading toward strategic competition with China, an ability to interpret and not be deterred by Russian nuclear rhetoric is essential. It’s the only way to protect European and American security while also preventing nuclear blackmail from becoming a tool of choice in 21st-century international relations.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Finland, Poland, Sweden, Ukraine, nuclear blackmail

Topics: Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons, Voices of Tomorrow

The problem is that Trump doesn’t deal in truth. He deals in whatever he thinks will get the most attention – get the most people to vote for him. Truth has never been a big part of his picture.

The problem is that the threat of nuclear weapons can and will be used to deter an adversary. Would the US have invaded Iraq to engage in regime change if Iraq was a nuclear state? Does North Korea fear regime change efforts by the US? Also, Eastern European states are not considered to be either essential to Russia’s survival as Ukraine is or threatening as are the NATO nuclear, conventional military, and industrial powers, especially the US. Putting western nuclear capable missile sites in any of those countries would change everything. Moscow’s attention will focus on destroying the missile sites… Read more »

“Peace deal,” “lasting peace”… is that really possible when dealing with Putin—the autocratic ruler of Russia; one in a long line? Do we really think that Putin, the aggressor, will agree to restore the full integrity of Ukraine’s territory, i.e., withdraw from the Crimea, Dombas, etc.? Anything less than that will be a victory for Putin. it will be a victory for all those who seek to violate the sovereignty of an independent nation.

Marlena Broeker argues that because Finland, Poland, and Sweden were able to increase their military postures in support of Ukraine when Russia increased its military aggression against Ukraine, the U.S. should increase its military support of Ukraine when Russia increases its military aggression against Ukraine, especially its use of nuclear threats against certain kinds of support for Ukraine. However, Broeker’s evidence is insufficient. In the face of significant Western support for Ukraine, Russia has used electoral manipulation (2004…), support for insurrection and invasion (2014…), and outright invasion and extended brutal war (2021…) in Ukraine. Russia’s nuclear threats might be coercive… Read more »