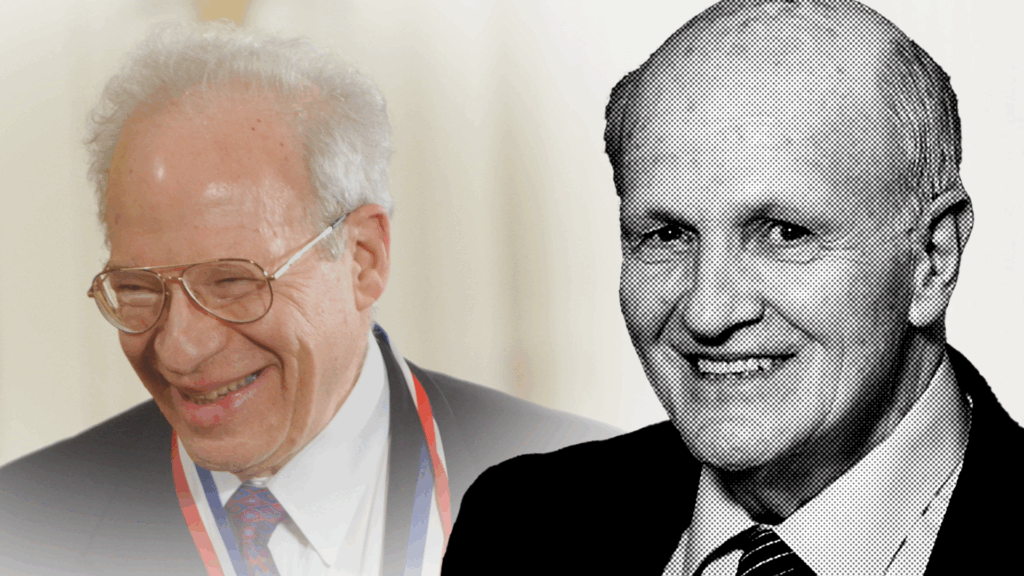

Richard Garwin, the socially responsible public and government advisor

By Frank von Hippel | May 23, 2025

Editor’s note: This essay is part of a collection of appreciations of Dick Garwin.

During a summer visit to the Los Alamos Laboratories in 1951, Richard Garwin, then aged 23, took the Teller-Ulam idea of using the X-rays from a fission explosion to implode a thermonuclear “secondary” and designed a test that was carried out in the South Pacific a year later. The explosion—700 times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb—showed that nuclear weapons were no longer war-ending; they were civilization-ending.

The explosion also launched Garwin’s career as a high-level government advisor, including as a member of the Strategic Military Panel of the President’s Science Advisory Committee (PSAC) from 1957 to 1973.[1]

But Garwin was more than a technological Mozart who continued to pour out ideas through an extraordinarily long professional career. He believed in democracy and went directly to Congress and the public when he felt the executive branch prioritized considerations other than the public interest. He did this even though it—predictably—resulted in President Nixon abolishing PSAC in 1973.

Garwin’s most public parting of ways with presidents began in 1967 when President Johnson was being accused by Richard Nixon, his expected opponent in the 1968 presidential election, of letting the Soviet Union get ahead of the United States in deploying defenses against ballistic missiles. Johnson’s science advisors explained that the defensive systems then being proposed could be overcome easily, but that worst-case analysts on the other side would simply drive bigger offensive buildups. Johnson nevertheless ordered the deployment of a nationwide “thin” ballistic missile defense to take the issue out of the political debate.

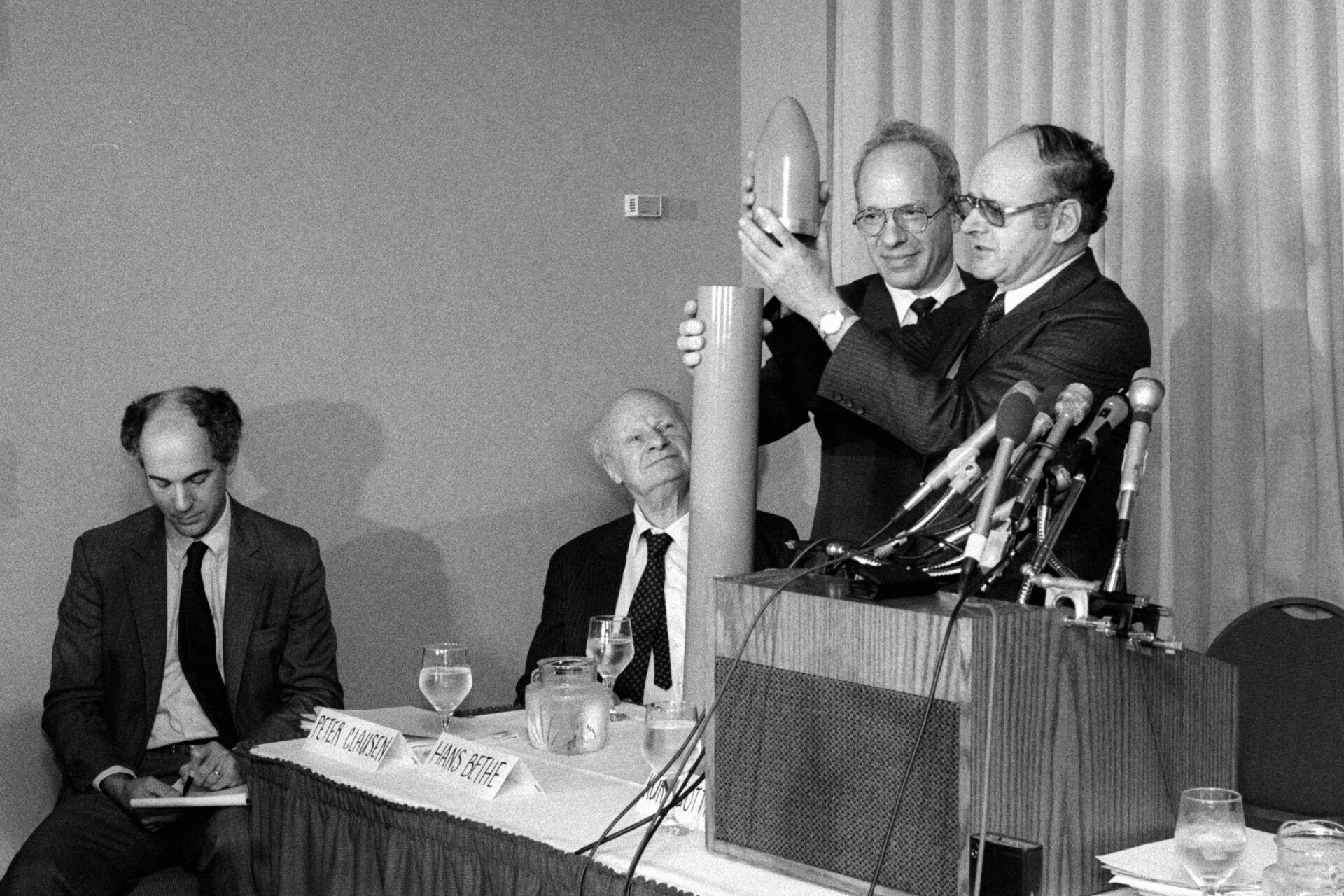

Garwin decided to go public with the arguments against ballistic missile defense and recruited Hans Bethe—a more senior and also independent science advisor who had been the director of the theoretical division at Los Alamos—to join him in laying out in a Scientific American article the many ways by which a ballistic missile system could be blinded or overwhelmed.[2]

I was a young assistant professor of physics at Stanford University at the time, and I remember being amazed to learn that the arguments Garwin and Bethe had made inside the government were based on “back-of-the-envelope” physics calculations—simple but robust enough to prove their point.

Soon, much of the public would also become interested.

The US Army, which was responsible for deploying the interceptor missiles, decided that these systems would be most protective if deployed in the suburbs of major US cities across the country. When the suburbanites learned that the interceptors would be nuclear armed (this was before terminal guidance had been developed), however, they immediately opposed their deployment, adopting a strong “not-in-my-backyard” (NIMBY) position. They feared the possibility of an accidental explosion of one of the warheads.

With the public engaged, members of Congress decided they, too, had to understand the issue of missile defense. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee—under the formidable leadership of Sen. J. William Fulbright, whom President Johnson called “Halfbright”—held hearings and invited the physicist critics to testify. Even though President Nixon moved the interceptors away from the cities and renamed the system, “Safeguard,” in 1970, Vice President Agnew had to break a 50-50 Senate tie vote to get another year of funding for the program. Nixon decided that the best he could do was to use it as a bargaining chip, and he negotiated the 1972 Soviet-US Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty, which limited each side to 200 interceptors (later reduced to 100). These were obviously useless against the thousands of nuclear warheads deployed on each of the countries’ strategic ballistic missiles at the time. The ABM Treaty, therefore, made it possible to agree on the first Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I), which was signed at the same time.

A decade later, in 1983, President Reagan, proposed his “Strategic Defense Initiative.” Garwin again was the leading technical critic. The program came to be ridiculed as “Star Wars” and was abandoned until President Trump recently revived it by calling for a “Golden Dome” that could defend the US homeland against both Russian and Chinese strategic missiles.

Garwin also led a review for the Nixon White House of the development program for a US Supersonic Transport (SST), a project of the Federal Aviation Administration to develop an intercontinental-range commercial supersonic transport aircraft to outstrip the French-British Concorde and Soviet Tu 144 programs. Garwin concluded correctly that the SST would not be competitive with existing big subsonic passenger jets and worried about the takeoff noise of such aircraft, even if they were forbidden to fly at supersonic speeds over land because of their damaging sonic booms. Once again, he went public, and Congress cancelled that program in 1971.

In 1973, President Nixon decided to eliminate both PSAC and the office of the President’s science advisor.[3] Garwin later commented that President Nixon’s decision to terminate both scientific advisory bodies was “because he and his political staff felt it insufficiently supportive of his goals, especially in the deployment of antimissile defense and the commercial supersonic aircraft…”[4]

Some of his colleagues were angry with Garwin for his role in causing PSAC’s demise. But he had already explained his position in 1970 when he came out against the Supersonic Transport program:[5]

I’m not a full-time member of the administration … and I feel myself in the same position as a lawyer who has many clients. The fact that he deals with one doesn’t prevent him from dealing with another so long as he doesn’t use the information he obtains from the first in dealing with the second. Since there are so few people familiar with these programs, it is important for me to give the Congress, as well as the administration, the benefit of my experience.

Garwin, in addition to his brilliance, was a government advisor of integrity and social responsibility.

Notes

[1] Richard Garwin, “Experience with the President’s Science Advisory Committee, its Panels, and Other Modes of Advice,” 1 April 2012, https://rlg.fas.org/Atlanta-20120401.pdf, 11.

[2] Richard Garwin and Hans Bethe, “Anti-Ballistic Missile Systems,” Scientific American, March 1968, 21-31. https://rlg.fas.org/03%2000%201968%20Bethe-Garwin%20ABM%20Systems.pdf

[3] Walter Sullivan, “Nixon to Revamp the Science Establishment,” New York Times, January 31, 1973. https://www.nytimes.com/1973/01/31/archives/nixon-to-revamp-the-science-establishment-difficult-to-assess.html

[4] Richard Garwin, “U.S. Science Policy at a Turning Point?” November 7, 2008. https://rlg.fas.org/US%20Science%20Policy%20at%20a%20Turning%20Point%202.pdf

[5] Horace Sutton, “Is the SST Really Necessary?” Saturday Review, August 15, 1970.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.