Only irreversible changes in nuclear disarmament can lead to a world without nuclear weapons

By Joseph Rodgers, Diya Ashtakala | June 4, 2025

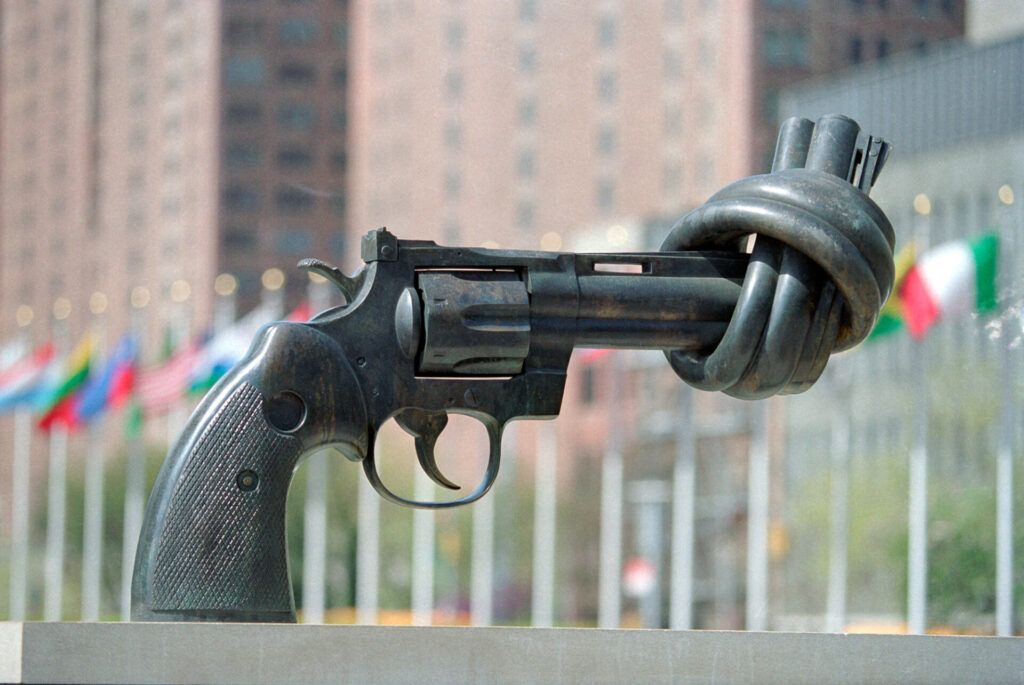

The "Non-Violence" sculpture by Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd stands on a platform near the public entrance of the UN in New York City. (UN Photo / Pernaca Sudhakaran)

The "Non-Violence" sculpture by Carl Fredrik Reuterswärd stands on a platform near the public entrance of the UN in New York City. (UN Photo / Pernaca Sudhakaran)

On February 13, President Donald Trump expressed his desire to ”denuclearize” the United States and pursue arms control with China and Russia. Two weeks later, President Trump stated that “it would be great if everybody would get rid of their nuclear weapons.” His remarks were met with both surprise and skepticism in the nuclear policy community.

Trump’s use of the term “denuclearize,” which likely stems from his experience in negotiating with North Korea, means complete nuclear disarmament. But it’s a goal that seems distant in today’s world. All nine nuclear-armed states are actively engaged in extensive nuclear modernization programs, with some even expanding their arsenal. Making the prospect of a nuclear weapons-free world, therefore, appears more like a fantasy than an achievable objective. This dissonance between rhetoric and reality highlights the enduring tension between the aspiration for a world free of nuclear weapons and the persistent challenges that stand in its way.

However distant and fantasist, denuclearization has been the subject of serious policy research and discussion. In particular, over the past three years, some government officials and experts have worked together to explore the challenges and opportunities associated with achieving and sustaining irreversible nuclear disarmament.

Irreversibility in nuclear disarmament first emerged in the final document of the 2000 Review Conference of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, or NPT. This document included language on making nuclear disarmament measures irreversible through verification, management, and disposition of fissile material. Then, the 2010 NPT Review Conference’s action plan included that all states parties would commit to irreversibility, along with verification and transparency when implementing treaty obligations. After these statements, the United Kingdom and Norway led studies, workshops, and conferences to develop practical measures toward irreversibility. These efforts yielded three important insights for achieving and maintaining a world without nuclear weapons.

Perceived security benefits. The first and perhaps most fundamental challenge lies in the deeply ingrained perception among nuclear-armed states that these weapons provide indispensable security benefits. The logic of nuclear deterrence, while controversial, posits that the existence of these weapons has prevented major wars between the most powerful nations. This belief, reinforced by decades of Cold War experience and the absence of large-scale conflict between major powers, remains a cornerstone of the academic understanding of international relations. Even smaller states like North Korea have pursued nuclear weapons as a means of deterring perceived adversaries and ensuring regime survival. Iran has also developed a robust nuclear hedging strategy, and senior Iranian leadership has threatened to build nuclear weapons. The acquisition or pursuit of nuclear weapons by states with perceived security challenges underscores the perceived value of these weapons as the ultimate security guarantor.

The security concern of perceived vulnerability is deeply rooted in the strategic calculations of nuclear-armed states and other states seeking to acquire nuclear weapons. This therefore represents a significant obstacle to nonproliferation and disarmament. Overcoming this obstacle cannot be achieved by dismissing these concerns as illegitimate. Rather, it requires a comprehensive approach that addresses the underlying security anxieties and provides alternative mechanisms for guaranteeing national security without nuclear weapons.

In 2019, the first Trump administration initiated a diplomatic effort—dubbed “Creating the Environment for Nuclear Disarmament”—to explore these obstacles through open-ended and integrative dialogue on practical measures to achieve nuclear disarmament. Other such efforts could involve strengthening international institutions, enhancing conventional deterrence capabilities, and fostering greater trust and cooperation among nations.

Technical challenges of verification. Even if the world were to disarm tomorrow, ensuring that states do not clandestinely rebuild their nuclear arsenals would be an immensely difficult task. Existing verification mechanisms, such as those employed by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), are designed to detect significant quantities of nuclear material, but they face limitations in their ability to provide absolute certainty. These limitations stem from the inherent difficulties in tracking and accounting for all nuclear material throughout complex nuclear fuel cycles, as well as the potential for states to employ sophisticated concealment techniques.

For example, the Rokkasho reprocessing plant in Japan handles vast quantities of plutonium, and even a small margin of error in measurement could translate into a significant amount of unaccounted material. A 2009 report on safeguards from the International Panel on Fissile Materials notes that just a 1-percent margin of error at Rokkasho, which has an annual throughput of about 8,000 kilograms of plutonium, could mean a measurement uncertainty of 80 kilograms—enough plutonium to build at least 10 nuclear weapons. Such discrepancies in accounting raise concerns about the potential diversion of fissile material for weapons purposes, even under a robust inspection regime.

The experience with Iran, where even the most intrusive IAEA inspection regime failed to fully satisfy some skeptics, demonstrates the limitations of current verification technologies and the challenges of building trust in a politically charged environment. Another technical challenge is the verification of fissile material production. US plutonium records indicate that the United States has produced 95.4 metric tons of plutonium, but there is a cumulative inventory difference of 2.4 metric tons of unaccounted-for plutonium. Many technical difficulties to achieve and verify disarmament still remain, and they will be enormously costly.

A global problem. Achieving and maintaining a nuclear weapons-free world is a global challenge that requires the active participation and engagement of all nations, not only nuclear-armed states. This includes non-nuclear weapon states, which have a vested interest in preventing further nuclear proliferation. International involvement is essential in shaping global norms, strengthening nonproliferation regimes, and holding nuclear-armed states accountable for their disarmament commitments.

There is also a critical need to foster a new generation of experts in nuclear policy, particularly from the Global South, of which most countries are non-nuclear weapon states. Such experts, with their diverse perspectives and experiences, can contribute fresh ideas and innovative solutions to the complex challenges of nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation. Building a sustainable and secure future free from the threat of nuclear weapons necessitates a truly global effort, one that transcends traditional divides and fosters collaboration. This requires investing in nuclear policy education and training programs, promoting dialogue on nuclear and broader security issues, and creating opportunities for young professionals from a wide range of backgrounds to contribute to the field of nuclear policy.

Achieving irreversibility. The dream of a world free of nuclear weapons may seem distant. However, as the global security environment is being flipped upside down, progress toward nuclear weapons reductions may prove possible. By acknowledging the perceived security benefits of nuclear weapons, addressing the technical challenges of verification, and fostering a global approach to disarmament, the international community can work toward a better future.

As the ongoing arms race between the United States, Russia, and China intensifies, Trump’s comments on denuclearization offer an important opportunity for state parties to engage in dialogues over disarmament and strengthen existing obligations in the wake of the recent NPT Preparatory Committee meetings and ahead of next year’s NPT Review Conference.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Donald Trump, IAEA safeguards, NPT, NPT Review Conference, Rokkasho, Trump administration, denuclearization, nuclear disarmament

Topics: Nuclear Weapons