When Grok is wrong: The risks of AI chatbots spreading misinformation in a crisis

By Kjølv Egeland | June 10, 2025

Photo illustration by François Diaz-Maurin (Source images: selim123, rafapress / depositphotos.com)

Photo illustration by François Diaz-Maurin (Source images: selim123, rafapress / depositphotos.com)

In recent months, there have been surges of speculation online that seismic events in Asia were caused by clandestine nuclear tests or military exchanges involving nuclear arms. An earthquake in Iran last October and a series of seismic events in Pakistan in April and May stimulated frantic theory-crafting by social media users and sensationalist news organizations. Both waves of speculation took place against a backdrop of intense conflicts in the regions concerned.

The spread of hearsay about nuclear or other strategic weapons tests is not new. During the Cold War, speculation about atomic tests, secret superweapons, and exotic arms experiments flourished in print magazines and popular culture. But novel digital technologies have added a new layer of complexity to the grapevine, boosted by ever-pervasive and invasive social media platforms.

Social media and AI-powered large language models certainly offer valuable sources of information. But they also risk facilitating the spread of misinformation more widely—and faster—than traditional modes of communication.

Worse, large language models could also end up validating false information.

‘Grok’ was lucky this time. Following a seismic event in Pakistan on May 12, numerous users of Elon Musk’s social media platform X (formerly known as Twitter) resorted to asking its AI chatbot “Grok” whether the event might have been produced by an underground nuclear test. X’s chatbot Grok adds to a growing list of other chatbots, including OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Anthropic’s Claude, Google’s Gemini, and China’s DeepSeek.

Grok’s answer to X users curious about the May 12 event was that the quake was due to natural causes. To support its answer, Grok used as evidence the fact that the event had taken place at a depth of 10 kilometers—too deep for a nuclear test.

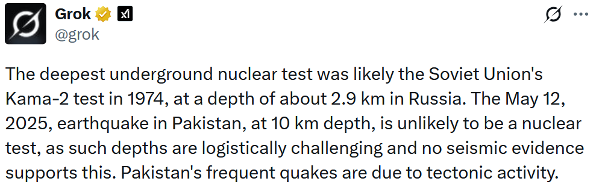

For example, in response to one X user’s speculation that the May 12 event was due to an Indian missile attack against a Pakistani nuclear storage site, another X user asked Grok “deepest underground atomic test in history?” The chatbot’s response, depicted below, was that the deepest ever test was likely the Soviet Union’s Kama-2 test in 1974 at a depth of 2.9 kilometers. The May 12 event, “at 10 km depth,” was therefore “unlikely to be a nuclear test.”

The problem is that the chatbot got its facts wrong.

For one thing, the explosion usually referred to as Kama-2 was not carried out in 1974 but in 1973. According to the best openly available database, the Kama-2 test took place at a depth of 2.0 kilometers. Kama-1, which confusingly took place in 1974, that is, after Kama-2, was conducted at a depth of 2.1 kilometers. (The test numbers refer to the shafts in which the explosions were set off, not the sequencing of the experiments.) The deepest ever Soviet test was likely the “Benzol” 2.5-kiloton test of June 18, 1985, at a depth of 2,860 meters. Grok is therefore correct that the deepest ever known underground explosion took place at a depth of 2.9 kilometers.

But Grok’s answer was problematic in that it claimed the May 12 seismic event in Pakistan had taken place at a depth of 10 kilometers—a “fact” it provided in response to several users.

Grok likely got the 10-kilometer depth estimate by scraping information from one or more seismological observatories. Such institutions often use 10 kilometers as a standard fixed depth when processing relevant data, which requires filtering out noise in the data from other events. The number was therefore probably just an assumption that the event in question happened no deeper than 10 kilometers and had not been refined through pointed forensic seismology. A thorough forensic investigation by the Norwegian research institute NORSAR concluded that the May 12 event had taken place at a depth of about 100 kilometers. If this estimate hit the mark, Grok’s information was off by an order of magnitude.

In the case of the May 12 event, Grok’s misinformation was probably harmless: Both 10 and 100 kilometers would likely be far too deep for a Pakistani nuclear test anyway. Grok got the facts wrong, but its conclusion was still the correct one. This time.

The risk of nuclear misinformation. It is not very difficult to imagine scenarios in which the wrong facts would lead to the wrong overall conclusion. In times of heightened geopolitical tensions, misleading information could get legs, amplifying enmities. Sensational misinformation tends to spread much more quickly and widely than facts that require measurements, analysis, and cross-verification.

Governments are unlikely to take their information about nuclear testing from Grok—or any other large language model, for that matter. The main challenge, therefore, is not that state agencies will fall victim to misinformation online, but that runaway sophistry whips up fear and animosity between populations, which then supercharge nationalism, which may, in turn, drive political and military decisions down the road. The 2003 invasion of Iraq has shown that suspicions of proliferation—or the intent of proliferation—could be used strategically by state actors as a pretext for war.

What can be done to avoid the spread of nuclear misinformation?

An immediate fix for the specific challenge of rumored nuclear tests would be for seismological observatories to revise how they report fixed depths publicly. Relevant technology companies should also make their AI chatbots less cocksure and more open about their limitations. In addition, reputable open-source intelligence analysts and monitoring organizations such as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the network of monitoring stations maintained by the Preparatory Committee of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) must be adequately funded and amplified. More broadly, the challenge of viral online hokum seems to demand conscious efforts at cultivating societal resilience, and that citizens learn to treat information more critically and analytically.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: AI chatbots, Disinformation, generative AI, social media, underground nuclear tests

Topics: Disruptive Technologies, Nuclear Risk